- 176 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Lost Towns of North Georgia

About this book

When the bustle of a city slows, towns dissolve into abandoned buildings or return to woods and crumble into the North Georgia clay. In 1832, Auraria was one of the sites of the original American gold rush.

The remains of numerous towns dot the landscape - pockets of life that were lost to fire or drowned by the water of civic works projects. Cassville was a booming educational and cultural epicenter until 1864. Allatoona found its identity as a railroad town. Author and professor Lisa M. Russell unearths the forgotten towns of North Georgia.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Lost Towns of North Georgia by Lisa M. Russell in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & North American History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

PART I

ANCIENT TOWNS

1.

CASSVILLE, BARTOW COUNTY

CASSVILLE, BARTOW COUNTY

A pleasant place to live, and an element of culture and refinement was apparent.4

In one final rebellion, the crisp autumn day turned dark. A foreboding sky brought cold rainfall on Cassville as Federal smoke rose from the smoldering remains. It was November 5, 1864.

At ninety years old, J.L. Milhollin remembers the day with perfect clarity. He was a fourteen-year-old boy; his father had died in July. J.L.’s father, John F. Milhollin, served as clerk of the inferior court from 1855 until he enlisted in the Confederate army in 1861. Killed in Virginia, his body was returned to Cassville in the summer of 1864. His wife and children lived across from the cemetery. When the order came to destroy Cassville, the Milhollin family lost their home just like their neighbors. The young Milhollin son covered his father’s grave with salvaged wood planks. He then fashioned a rough tent frame with a quilt attached to a fence and his father’s headstone. The Milhollin family spent the night on top of the grave. J.L. was the man of the family now, and he took responsibility. The next morning the young Milhollin found a slave cabin four miles away and moved in with their remnant belongings.5

Many families had evacuated long before this terrible day. Many left before the May 19, 1864 battle. Sally May Akin escaped with her husband, Confederate congressman Warren Akin, before the Union army came to North Georgia. Akin would have been sent to a Northern prisoner-of-war camp. The Akins escaped to Oxford, Georgia, to live as refugees.6

Refugees leaving Cassville toward Atlanta found that food was scarce and expensive. A turkey, if it could be found, was seventy-five dollars. Bacon was twenty-five dollars per pound, and a small package of needles for mending cost fifteen dollars.7

When the war was over, the Akins came back to Bartow (formerly Cass) County, but not to Cassville. Like many others, they moved to the new county seat in Cartersville. The family began a law practice in Cartersville near the train depot. That same practice remains open to this day and is run by Akin descendants.8

Not everyone left Cassville before November 5, 1864. Many women were war widows and had nowhere else to go. Huddled with their children, women refugees suffered through a sleeting day and watched their homes burn to the ground. Some returned to rebuild; some found homes elsewhere. Most never returned.9

Today, Cassville is a three-way stop to somewhere else. Once the largest city in northwest Georgia, 1840s Cassville was an educational and cultural center.10 According to the Etowah Valley Historical Society:

By 1849, Cassville was the largest and most prosperous town in northwest Georgia. Letters addressed to Rome, Georgia, were directed “via Cassville.” There were 4 hotels: Brown & Dyer, kept by Higgs; Cassville Hotel, kept by John Terrell; Eagle Hotel, kept by Aaron Burris; and the Latimer Hotel, kept by William Latimer. Leading merchants were George S. Black, T.A. Sullivan & John A. Erwin, J.D. Carpenter, Fain & Smith, Sam Levy, John W. Burke, Patton & Chunn, Humphrey W. Cobb, and George Upshaw. There was a Baptist, Methodist, Presbyterian and an Episcopal church.11

The town was home to doctors, lawyers and entrepreneurs. Cassville was a bustling, brick-paved town filled with business, education and culture. By 1864, Cassville was lost. The promising thirty-two-year-old town went up in smoke, first when it missed the train and, later, when Federal fires leveled the town.

COUNTY SEAT

In 1832 the Georgia legislature concurrently created Cassville and Cass County (now Bartow), making Cassville the county seat. Cass County was carved from former Cherokee territory. Gold prospectors invaded sovereign Cherokee land that was once off-limits to white Georgians. This early gold rush would lead to the desolation of the sovereign Cherokee Nation and to the Trail of Tears (see chapter 2).12

Cassville was a promising development centrally located in the Cherokee section. It became the legal center. Many barristers in the Cherokee Circuit maintained offices in Cassville. By 1833 the town had judges, lawyers, commissioners and a senator.13

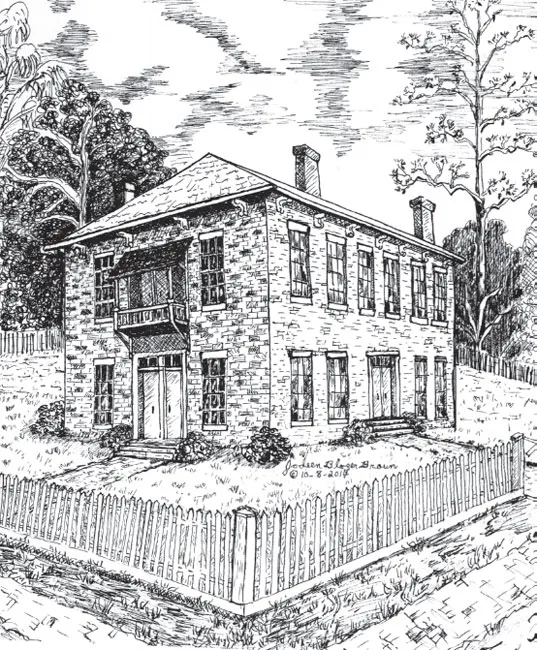

Local artist Jodeen Brown researched antebellum courthouses and reconstructed this pen-and-ink sketch of Cassville’s historic courthouse. Ink sketch by Jodeen Brown.

Within ten years of its birth, Cassville was growing. By 1836, forty homes occupied the city limits, with more farms outside of town. A brick kiln was the first manufacturer, supplying the construction boom of community buildings. The jail, the academy and the courthouse used the locally made bricks.

The courthouse was the most impressive building in Cassville. It cost $9,000 to build this two-story structure in 1836. The pen-and-ink image by local artist Jodeen Brown was re-created from this passage in Joseph B. Mahan’s book A History of Old Cassville: 1833–1864:

This was a rectangular, two-story structure with large double doors opening on each of the four sides. Most of the lower floor was given over to a courtroom with small vestibules inside the doors. Steps leading to several offices on the second floor were located in the vestibules at the ends of the building. In 1837 Adiel Sherwood in his Gazetteer termed this courthouse to be “one of the most elegant in the state.”14

THE RAILROAD SITUATION

When Western & Atlantic Railroad laid track through northwest Georgia in the 1840s, the route excluded Cassville. The closest access to the railroad would be two miles down the road at Cass Station. Several theories have existed as to why tracks never ran through the largest town in the region.

There is evidence that residents did not want the evil train coming through the young town. As in many towns of this era, the people did not want the railroad to change the character of their town. The only evidence that Cassville’s residents refused to allow the tracks to come through town were newspaper accounts that suggested the route was changed and that the citizenry celebrated because Cassville was not “contaminated by the vile railroad.” A local newspaper reported that they did not want the dirt, smoke and whistles disturbing students and “hard working newsmen.” This rhetoric may have been an attempt to make the best of an inevitable situation. The combination of geology and geography was the most likely reason.

This region in northwestern Georgia is a geologist’s playground. The area between Adairsville and Cassville in Cass County had a gravel plateau that would have made laying tracks to Cassville expensive and difficult. There is evidence that town leaders knew the value of the railroad coming to town and tried to make it happen.

Cass Station, two miles from Cassville, was one of the reasons Cassville never rebuilt after the Civil War. The railroad never ran through it. Courtesy the Atlanta History Center.

Whether it was the geography or the attitude of the town, the train never came closer than two miles to 1840s Cassville. The hotels lost vacancies, and business was down. Perhaps that explains an 1857 “Why go elsewhere?” advertisement in the Standard:

If you want to buy dry Goods, you will find Carpenter and Compton, G.L. Upshaw and Sam Kevy all with full stocks and anxious to sell, at fair prices.

If you want Family Groceries, go to McMurray’s and Brown’s where you can get anything in that line—even a little of the “juice.”

If you want a buggy or carriage made, call on Holmes, Headden, or Nelson.

If you want any blacksmithing done, go to the Headden’s, Holmes’ or Upshaw’s.

Want a Saddle? Go to Brown’s and have one made, any kind you may wish.

Anyone Sick? We have Kinabew, Griffin, Hardy, and Groves, all of them experiences in their profession.15

Cassville, despite the loss of the railroad, still had a great deal to offer. The citizens realized they needed to adapt to the changes. If Cassville could no longer be the center of commerce, it would be the cultural and educational center of North Georgia.

CULTURAL CENTER

Cassville was a young town populated with young people, as reported by a local newspaper: “A pleasant place to live, and an element of culture and refinement was apparent.”16 Most early citizens were in their twenties and thirties. They wanted to offer education and culture to the North Georgia area. Cassville wanted to become the cultural center, even as it was losing economic supremacy due to the railroad situation.

It was losing business as the railroad went to Cass Station and Cartersville. The hotels lost their monopoly and small businesses suffered from shipping issues, but Cassville adapted. In 1845, the same year the Cass Station was completed, the Thespian Society was organized two miles away. It was intended that young men would study and perform drama for public entertainment in the brick academy. The group’s first performances were two comedic productions, The Lottery Ticket and Family Jars. As usual for the times, men played all the parts.17

NOT ONE BUT TWO COLLEGES

The ambitious town decided to begin two colleges, to be run by other organizations but operating under a board of trustees made up of Cassville residents. Both colleges were established in 1852. Cassville Female College began classes in 1854, but the men’s college had a slower start. Cherokee Baptist College was set to open in February 1856, but one night in January a fire destroyed the building. The college still opened, and classes were held in private homes until the school was rebuilt.

Sarah Joyce Hooper was the first graduate of the women’s college—the first and only graduate in 1855. Wyley M. Dyer of LaFayette, Georgia, was awarded a bachelor of philosophy degree (BPh) on July 14, 1857. He was the first and only graduate that year from the men’s college.18

Cassville Female College and Cherokee Baptist College coexisted. Some gossips commented about the boys taking the long way around town to return to their college, having to pass the women’s college. Some things never change.

The colleges were closed in 1863 as war approached North Georgia. Records show that Cassville Female College became a place for both sides to ravage and occupy. Snipers killed ten Union soldiers and threw nine on the female college grounds, where the Federals were b...

Table of contents

- Front Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Dedication

- Contents

- Foreword, by Raymond Atkins

- Preface

- Acknowledgements

- Introduction

- PART I: ANCIENT TOWNS

- PART II: MINE TOWNS

- PART III: DROWNED TOWNS

- PART V: MILL TOWNS

- Afterword

- Notes

- Bibliography

- About the Author