![]()

Chapter 1

THOSE GUTSY PIONEERS AND THE NATIVE

WOMEN WHO WELCOMED THEM

The dogma of woman’s complete historical subjugation to man must be rated as one of the most fantastic myths ever created by the human mind.

—Mary Ritter Beard, 1946

It wasn’t easy to be wild back in the territory’s earliest days, but neither was it impossible. Though men definitely sat in the catbird seat, their wives found subtle ways to rebel. Like Elizabeth Babcock. When her husband forbade her to bring her good china to Michigan, Elizabeth hid it in flour barrels. That “Me Tarzan, you Jane” attitude still prevailed in 1921 when, to their shame, Michigan Supreme Court justices ruled that a man is the master of his wife whenever he is home. No wonder those ladies rebelled. Can’t you see them breaking into a happy dance each time the door closed behind their lord and master?

MARIE-THERESE GUYON CADILLAC

The French Guyon family had settled in Quebec in 1634, when Quebec was called New France. Marie-Therese was born to Denis and Elizabeth Guyon in 1671. Her mother was distantly related to French royalty. That was meaningless to young Marie-Therese, whose childhood experiences in the fur-trading community imbued her with a business sense that helped greatly when she found herself in Fort Ponchartrain. She had grown up playing with children of the Algonquin, Huron and Iroquois tribes, enabling her to move easily among Michigan’s tribes without fear or prejudice.

Madame Marie-Therese Guyon Cadillac and her traveling companion, Anne Picote de Bellestre, were the first two white women to arrive in the settlement of Fort Ponchartrain du De Troit. With them was Cadillac’s thirteen-year-old son. The party arrived in May 1702. Both women came from Montreal, Quebec, to join their husbands. Cadillac was married to Antoine de la Mothe Cadillac, commander of the fort. Bellestre’s husband was his first lieutenant. The native tribeswomen greeted them with great excitement and said they were the first French women they had ever seen. Also on hand to greet the party was Cadillac’s nine-year-old son, who had accompanied his father. She also had two daughters, but they had remained in Canada and later joined the family.

Antoine Cadillac had ties to French aristocracy. His family coat of arms would later grace the Cadillac automobile. He also had an abundance of blind ambition that had led to his being transferred from a spot near present-day St. Ignace to this new post at Fort Ponchartrain du De Troit, located in the straits between Lake Huron and Lake Erie. Le detroit is French for “the strait.”

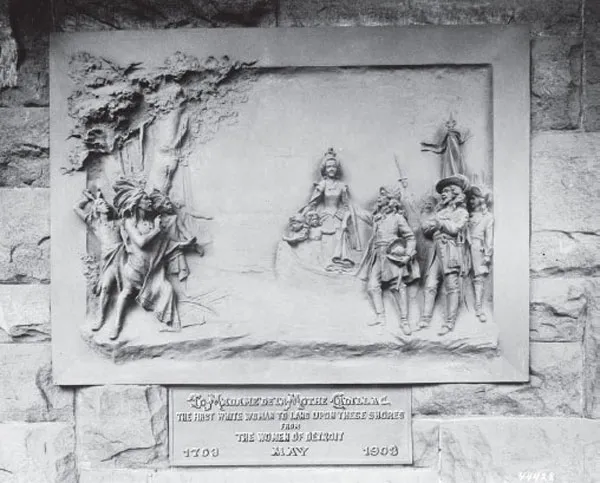

A postcard depicts the arrival of Madame Cadillac in what is now Detroit. Detroit Historical Society.

The plaque in the Detroit Art Museum reads, “To Madam de la Mothe Cadillac, the first white woman to land upon these shores from the women of Detroit.” Library of Congress.

Marie-Therese Cadillac and Anne Picote de Bellestre were already close friends, having met during their days at a strict boarding school operated by nuns at the Ursuline monastery in Quebec City. There they learned the arts needed by society girls of their time: home management skills, needlework, art, music, comportment and social graces. Now their lives had again intertwined as they set out to settle in and bring a much-needed touch of female refinement to an unimaginable wilderness. Their incredible journey had begun eight months earlier, when they climbed into one of the twenty-five canoes making the trip and traveled 750 miles through hostile Iroquois Indian territory. Both women took their turns paddling across Lake Ontario, then called Lake Frontenac. They had portaged around Niagara Falls.

Cadillac’s friends tried in vain to dissuade her. She replied, “Do not waste your pity on me, dear friends. I know the hardships of the journey, the isolation of the life to which I am going; yet I am eager to go, for to a woman who truly loves her husband there is no stronger attachment than his company wherever he may go.”

The reality was beyond anything either woman could have imagined. Because the fort had no doctor, ministering to the sick fell to Cadillac, who was assisted by Bellestre. They drew on remedies the nuns had used and also those they had learned from their native neighbors back in Canada. The latter involved growing herbs and turning them into potions and poultices.

While living in Fort Ponchartrain, Marie-Therese and Antoine had more children, bringing the final count to thirteen, seven of whom lived to adulthood. In addition to caring for an ever-growing family and serving as medicine woman, Marie-Therese helped Antoine in his business dealings, filled in for him when his travels took him away and arranged schooling for both the white and native children. It could be argued that had it not been for her tireless devotion to her duties in those early days, a city other than Detroit might have become Michigan’s largest. She has been described as pious, intelligent, business smart and possessing an outstanding devotion to humanity. No doubt those sterling character traits were called upon repeatedly in her time at the fort.

Eventually, Antoine fell out of favor with the powers that be and was assigned to a lesser Louisiana post. Following that, the family was sent to France, where Antoine died in 1736 at age seventy-eight. Marie-Therese died ten years later. She was seventy-five.

MADAME MAGDALAINE LAFRAMBOISE

Madame LaFramboise wasn’t a pioneer. As an Ottawa Indian, she was already on hand to meet new arrivals. One of those newcomers was Joseph LaFramboise, a member of a prominent French trading family. He first came to her village when she was fifteen and quickly fell in love with the beautiful Indian maiden.

Mackinac Island’s rich history begins with the Indians who first inhabited it. Magdalaine’s tribe, the Odawa (Otttawa), were first called the Algonkins and lived on and near the St. Lawrence River area. The Iroquois eventually drove them to the Michilmackinac area. The first white man to explore the region was Jean Nicolet in the early 1600s. That and the burgeoning fur trade cemented the ties between the French and the Ottawa.

The lives of the French Canadians and natives had become intermingled over the years, and Magdalaine, born in 1780, was the daughter of another French fur trader, Jean Baptiste Marcot, and his Ottawa wife, Marie Nekesh. Though there are no images of her, history reports she was beautiful, having inherited the best of both parents: natural good looks coupled with French elegance.

One thing they had in common was unwavering Catholicism. Joseph’s devotion to the faith was said to be second only to that of ordained priests. The two married when she was sixteen in an Indian ceremony but were later remarried by a Catholic missionary. A year later, Magdalaine bore her first child, a daughter she named Josette in honor of her beloved husband. Joseph took his wife and daughter with him when he visited and conducted business with the various tribes in the Michigan forests. Magdalaine proved a valuable partner, for though she was unable to read, she spoke four languages: English, French, Ottawa and Ojibwe. They traveled through what is now Michigan with a servant or two and a dozen or so oarsmen, called voyageurs, navigating two pelt-filled boats through the scenic waterways. Once the business had been completed, the LaFramboise family returned to Mackinac Island, where they spent their summers.

This idyllic family life came to an abrupt end in 1809, when an Indian named White Ox, believing falsely that he had been cheated, killed Joseph. Indians in another village eventually caught Joseph’s killer and delivered him to LaFramboise so she could have her pound of flesh. Tempting though that must have been, her abiding Catholicism required her to forgive him. The rest of the village was less pious, and though his life was spared, he lived the rest of his life as a social pariah. White Ox was dealt with in the Ottawa version of an Amish shunning.

Her husband’s death pushed LaFramboise deeper into the family’s prosperous business, as she was then forced to take over Joseph’s responsibilities while still caring for her young family, which by then included a son, Joseph. It was a logical choice, as her options were limited. She had learned the fur business from her husband and, before that, her father, so despite having no formal education, she had an innate business sense.

By all accounts, she did an outstanding job. She traveled the territory and was well known and respected in the Grand River Valley. Her fluency in four languages made it possible to negotiate with her diverse clientele in their own languages, an advantage most other traders lacked. Her trading post was on the river east of Grand Rapids in what is now the village of Ada. One way she cemented her relationship with the natives was by extending them credit when no one else was willing to take the risk. That way, the trappers could obtain what they needed for their winter’s work and pay her in pelts come spring.

Another step she took had to have tugged at her conscience a bit, but she felt it necessary. Though providing liquor to the natives was forbidden by her church and frowned upon by most, rightly or wrongly, LaFramboise sidestepped the issue by offering a watered-down, tobacco- and herbenhanced, less intoxicating product. Most trappers refused to negotiate with a trader without first obtaining some firewater. Responding to those demands was the only way she could have remained in business. This was affirmed by Potawatomi chief Topenebee’s statement to Indian agent Lewis Cass in 1821: “Father, we care not for the land, or the money, or the goods; what we want is whiskey.”

Among her competitors, the biggest, the American Fur Company, was owned by the wealthy Astor family of New York. When the Michigan Astor representative proved unable to steal her business, they took her into the company, where she worked until retirement.

LaFramboise earned the respect of all for her business savvy and integrity. She flourished and eventually became wealthy enough to send her children to the best schools in Montreal. She knew the phenomenal success she had achieved without an education had been a fluke and wanted to make sure all children had every advantage.

When Josette, her firstborn, married fort commander Captain Benjamin Pierce, whose brother was future president Franklin Pierce, it was a social highlight to remember. Benjamin’s military colleagues wore full dress uniforms, while female guests sparkled in the latest fashion. But with the exception of the bride, LaFramboise was the showstopper. She wore a deerskin dress that in its simple elegance showcased the intricately beaded designs that were further enhanced with porcupine quills. It was a work of art.

Josette died of childbirth complications on November 24, 1820, a few days after giving birth to her second child, Benjamin Langdon. The infant also died. Her first child was a girl, Josette Harriet. Had Josette lived until his inauguration on March 4, 1853, the daughter of an Ottawa Indian mother and French Canadian fur trader would have been a sister-in-law of the president of the United States. The Pierce family’s presidential association didn’t end with Franklin. Barbara Pierce Bush, wife of the forty-first president and mother of the forty-third, was Franklin Pierce’s direct descendant.

LaFramboise sold her business to Rix Robinson and moved permanently to Mackinac Island in 1821. Robinson was an Astor agent who, among his other accomplishments, founded the city of Grand Haven along with Presbyterian Reverend William Montague Ferry.

A postcard shows an artist’s rendering of the fort at Mackinac, with the bridge to Mackinac Island in the distance. Author’s collection.

Picturesque Mackinac Island is where Magdalaine LaFramboise summered before returning permanently in retirement. Library of Congress.

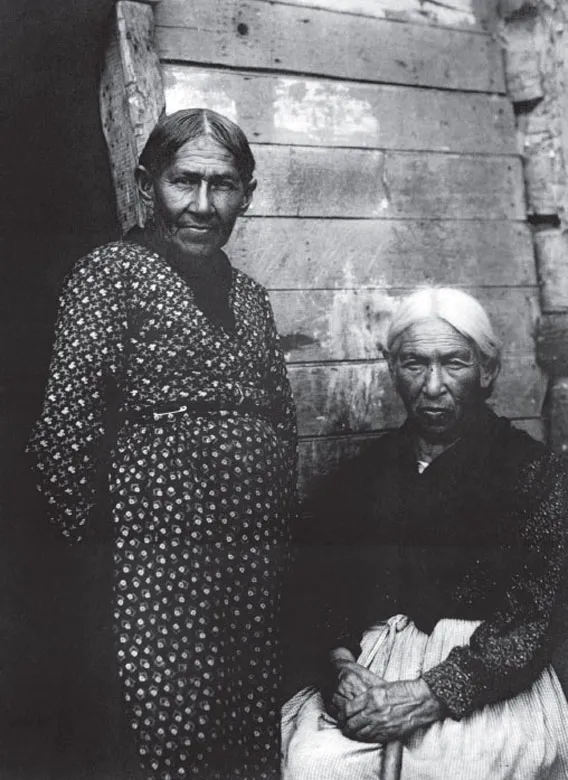

Ottawa Indian women pose in typical dress on Mackinac Island in 1903. Library of Congress.

Back home on Mackinac Island, Magdalaine worked hard in the local Catholic St. Anne’s Parish, even to the extent of keeping the congregation going during a few years when there were no priests. She is also remembered for training young Ottawa women to become schoolteachers. She wanted to make sure that Ottawa children whose families could not afford to send them to faraway schools, as she had done, also received an education that would permit them to find employment. When the church had to be moved, LaFramboise donated the property next to her house, asking only that she be buried under the altar at her beloved St. Anne’s. Before her death in 1846 at age sixty-six, LaFramboise made time to learn to read French and English, languages she had long spoken.

JANE JOHNSTON SCHOOLCRAFT

Thirty-seven years before Michigan became a state, Jane Johnston was born in 1800 in Sault Ste. Marie. Her Ojibwe mother Susan’s Indian name was Ozhaguscodawayquay, meaning Woman of the Green Valley. She was the daughter of Waubojeeg, the chief of the north shore of Lake Huron and both shores of Lake Superior Ojibwes.

Jane’s father, John Johnston, was a fur trader who had immigrated to the territory from Belfast, Ireland. Her travels with him to Ireland and England gave her a world perspective unknown to most of her contemporaries. That dual heritage also meant she was fluent in the Ojibwe language, learned the history of the tribe through age-old stories passed down in the oral tradition and grew proficient in native needlework. From her father, young Jane learned to speak, read and write in English. Her reading textbooks were her father’s Bible and other tomes in his massive library.

Her native name, Bamewawagezhikaquay, translates to Woman of the Sound that Stars Make Rushing through the Sky. Perhaps it was that lyrical name that inspired her to become the first known native female poet and writer. One also has to wonder if she found it refreshingly liberating to trade that mouthful of a moniker for “Jane.”

She began writing in her mid-teens, creating poems and capturing the stories of her people. To further spread the Ojibwe culture, she also translated some of the tribe’s songs into English. Literature was something she had in common with her husband, Henry Rowe Schoolcraft, whom she marrie...