![]()

1

THE STORY OF THE UNION’S LOST GOLD

THE KEEL MOUNTAIN TREASURE

Keel Mountain, near Gurley, has managed to stave off development and remain nearly untouched. Like so many people before me, I believe that the pristine land on Keel Mountain is hiding a secret, one dating back more than 150 years.

In April 1862, Brigadier General Ormsby Mitchel of the U.S. Army made an unexpected and brash maneuver with his Army of Ohio and marched on the city of Huntsville, Alabama, taking the townspeople by such surprise that no one offered resistance. The capture of Huntsville gave the Union army control of most of the larger cities between Huntsville, Alabama, and Nashville, Tennessee.

From his new headquarters in Huntsville, General Mitchel was able to observe the populace of the growing southern city. The Union troops did not witness open rebellion from the townspeople, but they sensed a feeling of unrest that General Mitchel found disconcerting. But he had a more immediate problem—Huntsville lacked a standardized system of currency.

By this point in the war, the Confederate script was useless to the locals, and in any case, Union soldiers would not accept it as a form of payment. But shopkeepers and citizens in Huntsville would not accept the U.S. currency, fearing they would be branded traitors to the Southern cause. General Mitchel was convinced that finding a standard medium of currency would stabilize the local economy and cool some of the resentment toward occupation. So General Mitchel came up with a bold plan: he asked the War Department for $50,000 in gold coins.

Keel Mountain today. Author’s collection.

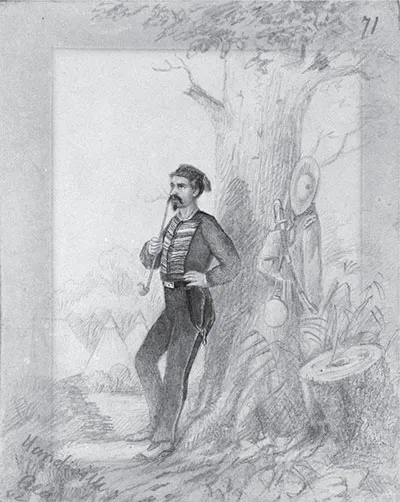

Drawing of First Lieutenant William Urlan, Company B, Camp at Huntsville, 1862. Library of Congress.

At any other time, this request would have been absurd, but timing and circumstance happened to fall on the general’s side. After seizing Huntsville with relative ease, Mitchel was considered something of a hero, and he was promoted from brigadier general to major general. General Mitchel had gained a reputation for leadership, and the War Department granted his request and sent the gold from Washington to the army headquarters in Nashville.

Once the gold was in Nashville, the problem became how to get the gold to Huntsville. Mitchel assembled a small unit from his Fourth Ohio Cavalry division and devised a plan to sneak through the countryside to Nashville, collect the gold and secret it back to Huntsville. Army leaders thought the smaller unit would stand a better chance of avoiding Confederate cavalry or one of the guerrilla units that roamed the low, rolling hills of northern Alabama and southern Tennessee.

It was mid-September when the detachment of heavily armed cavalry troopers left Huntsville for Nashville. The group was led by a first lieutenant and consisted of a sergeant and nine enlisted cavalry soldiers. This small group was able to navigate its way to military headquarters in Nashville with few problems. Once at the camp, the soldiers rested and agreed to set out for Huntsville with the gold at the next nightfall.

The next night, the soldiers loaded the gold coins into two large leather bags and put them in strongboxes, which they fastened securely to a pack mule. One of the enlisted cavalry troopers would lead the mule behind his horse. The soldiers then set out for the return trip, but this part of the journey would not go as smoothly.

It was near the town of Belleview that the Union soldiers encountered their first problem—one of the group’s scouts reported a Confederate cavalry detachment camped west of the town. The lieutenant, attempting to avoid the Confederates, moved his troops east toward Booneville to take a different route. But this course led them into the path of a group of Southern guerrillas hidden in a tree line, and the Rebels opened fire on the Union soldiers.

The Union soldiers fled the firefight as fast as their horses could gallop, stopping a few miles down the road to set up an ambush for the guerrillas following them. Four of the Union troopers took a defensive position while the rest of the detachment continued south, protecting the gold. The Union troopers were able to kill several of the guerrillas but three of the four Union soldiers were killed in the battle. The remaining soldier caught up with his group near Fayetteville, which happened to be where they encountered a much larger group of Confederate marauders.

This time, they avoided being spotted by the new band of guerrillas by riding through woodland trails, but when they got back on the road, they ran directly into the guerrillas’ scouting party. The troopers were able to kill one of the guerrillas, but one escaped and warned his band of thirty men. The men chased the small Union detachment, which was riding furiously toward the state line at Old Elora Place.

Crossing into Alabama, the Union soldiers thought they had lost their pursuers and went through New Market, heading for Lewis Mountain and the Flint River. They thought they would be able to follow the river south to the Union outpost at the John Gurley farm, but little did they know, they had been spotted by a third group of Confederate guerrillas who had a hideout in the nearby valley known as Potts Hollow.

The guerrillas from Tennessee were also catching up to the Union troopers, who were now being charged on two sides. This left the lieutenant with only one choice. He ordered his men to ride up the slope of Keel Mountain, which was looming in front of them. He thought that if they could make it to the top and set up a defensive position, Union troops from the other side of the mountain would hear the firefight and come to their rescue.

Union soldiers on Lookout Mountain. Library of Congress.

Rendition drawing of the camp of General Alexander McDowell McCook near Stevenson, summer 1862. Library of Congress.

As the soldiers were riding up the mountain, the guerrillas began firing on them, killing one trooper and the pack mule carrying the gold coins. The trooper leading the mule jumped off his horse and cut the boxes loose from its back. He took the leather satchels out of each box and began dragging them up the slope of the mountain. A round from the guerrillas struck the trooper in the neck, mortally wounding him and knocking him into a depression—along with the coins. His weight, combined with that of the coins, pushed him to the bottom of the hole; the leaves then covered his body, making him virtually undetectable.

This is where we meet the man at the crux of this story: sixty-yearold Jeremiah McCain. The guerrillas continued to force their way up the mountain after the federal troopers, oblivious to the fallen soldier and the gold—all of the guerrillas, that is, except for Jeremiah McCain. McCain had seen the trooper fall and went into the hole to plunder the body. Imagine McCain’s surprise when he opened the bags and discovered the gold coins. Being greedy and having no desire to share his newly discovered treasure, he buried the satchels in a hole near the top of the mountain and covered it with stones and leaves. He then counted off exactly seventy-six paces from a nearby oak tree.

Jeremiah McCain survived the skirmish on Keel Mountain, as did most of the guerrillas. Only two of the Union troopers survived to make it back to Huntsville to report the lost gold. General Mitchel was irate at the loss of so much gold and sent several patrols and search parties to Keel Mountain in search of the treasure, but it was never recovered. The army eventually wrote off the gold as being stolen by the Confederates. Mitchel also sent armed patrols to capture any Confederate marauders in the area, and this is how Jeremiah McCain met his fate. Before he was able to return for his gold, he, along with several other guerrillas, were attacked by Union forces near New Market.

During this skirmish, McCain took a bullet to the stomach, and like so many others who had been gut-shot, caught an infection and died a slow, painful death. On his deathbed, he tried telling one of his comrades of the existence and location of the gold, but in his pained and delirious state, his story was unintelligible. Still, people knew the gold had last been seen on Keel Mountain, and the story was passed from one generation to the next. In the last century and a half, many have searched for the treasure, which is now worth $1.5 million.

How much of this story is true? The occupation of Huntsville by General Mitchel, the need for currency and the presence of numerous bands of guerrillas in rural Alabama and Tennessee were real. And one of the groups did include a man named Jeremiah McCain. But the story of the gold? It is repeated often in the South, listing differing cities where the stash may have been lost. There are also plenty of stories about Southerners who hid their gold from Union troops, and in at least one case, a Civil War treasure was discovered.

It happened near Demopolis, Alabama, in 1926. Newspaper accounts at the time reported that Gayus Whitfield found gold hidden by his grandfather General Nathan Bryan Whitfield, using a map left to Gayus by his father, Boaz Whitfield. The general was “one of the richest of Alabama’s pre-war citizens,” according to an Associated Press story, and the builder of the Greek Revival mansion called Gaineswood that today is a museum offering tours.

What did the general’s grandson discover in 1926? Gold worth $200,000, which would be more than $2.6 million today. It was discovered eighteen miles from Demopolis “in an old powder can which crumbled at touch.”

Did You Know

Dan Sachs wrote a song, “Lost Keel Mountain Gold,” about the lost treasure.

![]()

2

THE LEGEND OF THE MISER’S GOLD

The legend of a miserly north Alabama man is reminiscent of the Charlie Daniels song “The Legend of Wooley Swamp”:

People didn’t think too much of him

They all thought he acted funny

The old man didn’t care about people anyway

All he cared about was his money.

He’d stuff it all down in Mason jars and bury it all around

But on certain nights if the moon was right

He’d dig it up out of the ground.

He’d pour it all out on the floor of his shack

And run his fingers through it.

Old Lucias Clay was a greedy old man

And that’s all there ever was to it.

Copyright © Universal Music Publishing Group

The gentleman in the Alabama story is one C.S. Sharps, who was a businessman in Lauderdale County in the late 1890s. Not only did he mistrust the bank, but he also had a quirk—he would only accept payment in the form of gold coins. Every few weeks, he’d take the accumulated coins and bury them in the woods near his gristmill just outside of Florence.

Sharps was already established as a businessman when he purchased the White Mill in 1897. It was one of the oldest in the area and had been profitable under the ownership of Sherwood White. Sharps, a consummate businessman, planned to make it even more successful.

Northeast view of Florence, June 22, 1862. Library of Congress.

Man with shovel. Library of Congress.

Located on Second Creek in the eastern portion of the county, the mill was already being utilized by many area farmers to grind corn for their personal use. Soon, Sharps began buying crops from local farmers and grinding them into flour, which he would then sell back to the people in the area. It was profitable for everyone: the farmers had more opportunity to sell crops, additional local people were put to work in the mill, the residents could purchase cheaper flour and Sharps watched the money roll in. His system was working so well that he purchased one hundred acres of nearby forest to clear and plant new crops.

Now remember, Sharps was eccentric. As he obtained more and more gold coins, Sharps became the subject of rumors, as people made guesses about what he did with his fortune. They could only guess, until one day, when a young man working at the mill came forward with an outrageous story. That man was Sharps’s nephew Grady, who was the mill bookkeeper.

Grady told several locals that every week, his uncle would count the gold he had taken in during the week and then put it in old feed sacks. He would then secretly take the bags into the woods when he thought no one was around. On more than one occasion, Grady followed Sharps into the woods, but knowing the old man’s temper, he would never follow too closely for fear of discovery. He never got close enough to determine where he was taking the sacks of gold.

After a couple of years, Sharps decided to use some of his profits to make much-needed repairs to the mill and upgrade some equipment. He hired crews of men to do the work while he oversaw the projects.

While supervising a crew on the roof one day, Sharps lost his footing and slid down the sloped roof. Several of the workers tried to grab the old man, but none was successful. He fell into the retention pond below. Sadly, he was unable to swim, and even though some of the workers jumped in ...