![]()

Chapter 1

VAUDEVILLE EMBRACES THE MOVIES

The inclusion of films in vaudeville bookings helped popularize movies and, in the process, hasten the demise of vaudeville. In downtown Cleveland, the Empire, Lyric and Prospect Theaters ranked among the most important in nurturing the allure of movies.

In 1900, the city’s first large playhouse dedicated strictly to vaudeville debuted on Huron Road. Attracting Cleveland’s wealthiest and most prominent citizens, the 1,400-seat Empire Theater featured twenty-four exclusive boxes decorated with green draperies and white-enameled chairs, a beautiful complement to the ivory and gold proscenium arch. Demand for opening-night tickets justified a special auction that commanded premium prices.

From the initial performance, either short Biograph or Edison Kinetoscope films enhanced the vaudeville programs. In 1901, customers packed the Empire to view “the first authentic movie” of Queen Victoria’s funeral. Yet live performances remained the major attraction. A few weeks after the theater’s debut, the Plain Dealer predicted an obscure escape artist “will certainly not be unknown on his next visit, as before the week is out his mystifications will become town talk.” The newspaper correctly anticipated the rise of Harry Houdini. Two years later, juggler W.C. Fields added a few new tricks to his routine prior to emerging as an entertainment legend.

In 1904, the Empire abruptly abandoned vaudeville, choosing not to compete with the powerful Keith organization that had purchased the nearby Prospect Theater. The Empire struggled to mold a new niche in Cleveland’s entertainment market. It reopened as the winter home of the Garden Theater Opera Company (which performed in an outdoor theater on Euclid Avenue), but the experiment lasted only seven weeks. William Farnum, star of the stage version of Ben-Hur, created a stock company to finish the season. Farnum assumed the male starring role in productions of Romeo and Juliet, The Three Musketeers, Camille, Spartacus and many other classics. Within ten years of his short Empire Theater undertaking, Farnum reigned as one of Hollywood’s highest paid actors, earning $10,000 per week. He continued in movies until a year before his death in 1953.

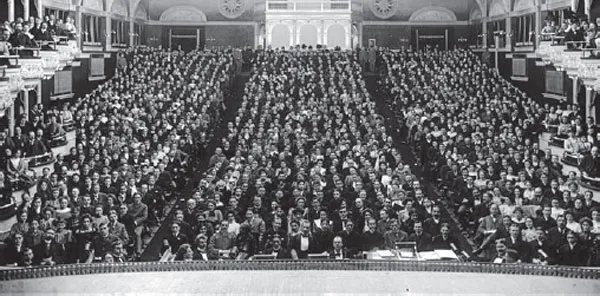

The Empire Theater exhibited movies to supplement its vaudeville acts. Courtesy of Cleveland Public Library, Photograph Collection.

Taken on March 7, 1900, with a revolutionary “electric flash,” this photograph of the Empire Theater’s audience hung framed in the theater’s lobby by the end of the performance. Courtesy of Cleveland Public Library, Photograph Collection.

Following a summer break, the Empire launched the 1905 fall season as a burlesque house and added a five-hundred-seat balcony. Here, the young monologist Will Rogers worked on perfecting his art. Wrestling matches soon developed into a strong box-office attraction while movies remained as part of the burlesque programs.

Although never quite achieving star status, Lillian Graham and Ethel Conrad composed one of the Empire’s most unique acts. In 1912, Lillian (with Ethel serving as an accomplice) shot, but did not kill, millionaire New York hotel owner W.E.D. Stokes. The wealthy executive had arrived at Lillian’s apartment to pay her blackmail and to retrieve letters that he had written to her. Later facing an attempted murder trial, Lillian mysteriously disappeared while free on bail. Discovered in a Poughkeepsie hotel using an assumed name, she claimed someone had kidnapped her, but she could not supply any specific information because her mind had gone blank.

During the trial, the defense proved that her apartment had been ransacked prior to the shooting, while the majority of Stokes’s letters had been stolen after the incident. A jury acquitted both Lillian and Ethel. Capitalizing on their previous showgirl experience, the duo (calling themselves “the shooting show girls”) developed The Girls Who Dared musical production, which consisted mainly of the singing of a few songs. Religious groups lobbied unsuccessfully to prevent the showgirls’ Cleveland appearance, but booing from the audience caused the performers to leave town in the middle of the booking.

In 1914, an unknown Ed Wynn appeared in a chorus just prior to his rise to fame in the Ziegfeld Follies. The Empire continued the burlesque and wrestling format until its closing in 1922.

Originally intending to operate a German playhouse, the Lyric Theater owners launched their new venue in 1904 in a remodeled German Lutheran church situated on East Ninth Street at Bolivar Avenue. Even prior to the theater’s debut, stockholders had decided against the German concept and attempted to sell or lease the pristine 1,150-seat theater highlighted by an “art nouveau” interior with six large chandeliers hanging from the ceiling.

Following a brief lease by a stock company, two Detroit capitalists conceived of a concept so unique that they applied to patent their idea. The duo planned to initiate grueling four-a-day vaudeville performances that also included movies. Intending to rename the playhouse the Merchant’s Theater of the United States, their innovative idea consisted of selling all the tickets to local businesses to give away as sales promotions. Theater patrons would never purchase a ticket; in fact, no theater box office would even exist. Never successfully implementing the scheme, the Detroiters sold the Lyric to another vaudeville owner who initiated “high class vaudeville, ideal for ladies and children.”

The theater presented three performances per day (which included both vaudeville acts and movies) that cost ten or twenty cents. Making good on the promise to appeal to children, the theater manager scheduled numerous animal acts—dogs, horses, lions, bears and elephants. The combination of low ticket prices and family appeal seemed ideal. Yet, in 1906, a bondholder purchased the Lyric at a foreclosure sale.

A new management team retained the vaudeville acts and improved the movie format by introducing “cameragraph,” promoted as the latest innovation in motion pictures. A nursery in the basement, filled with toys and dolls and staffed by two nurses, accommodated young children. But in 1908, the Lyric abruptly shut down without even notifying incoming performers of the closing.

In 1909, the Grand Theater (the reopened and renamed former Lyric) debuted with excitement not confined to the stage. In the Grand’s first two months, a gunman flashed a loaded revolver in the theater lobby following an argument with a ticket seller; a fireman rescued a puppy from an abusive boy but suffered a concussion when a theater electrician hit him over the head as he attempted to smuggle the dog into the theater; and police arrested the theater’s manager for employing children under the age of fourteen. On the stage, the vaudeville and movie format continued. Movies of Pittsburgh defeating Detroit in the World Series topped the year’s film attractions.

In 1911, clarinet virtuoso Philip Spitalny, who would later play an important part in the early success of the Allen Theater, made one of his first stage appearances at the Grand. Beginning in 1912, the Grand exhibited movies all day on Sundays. During the showing of the five-reel epic The Battle of Gettysburg, the Empire employed singers and instrumentalists to accompany the film. In 1916, films of ex-president Roosevelt’s trip through the African jungles drew large crowds. By 1919, the vaudeville-movie format still continued, but feature-length movies had become the major attraction as famous actors (including Douglas Fairbanks) and directors (such as D.W. Griffith) attracted large audiences.

Following its closing in 1921, the Grand reopened the next year as the New Empire burlesque house to replace the razed Empire on Huron Road. The theater garnered its best attendance from boxing and wrestling matches. In 1925, an unusual match pitting heavyweight versus lightweight contestants did not involve grapplers or pugilists; customers instead enjoyed a battle composed of different-sized shimmy dancers. Adhering to a policy of “smoke if you like,” the Plain Dealer characterized the New Empire as a “smoke-filled auditorium fit only for a rowdy element.” In 1928, the second incarnation of the Empire closed.

The Prospect Theater debuted in 1904 with the mission of presenting “high-class plays at a low scale of prices.” The grand opening developed into a social affair with many of Cleveland’s upper crust attending a performance presented by a stock company. The format lasted a mere seventeen weeks until the Keith organization purchased the theater and turned it into a vaudeville house with accompanying Biograph movies. Films of the 1906 San Francisco earthquake generated especially large audiences. Harry Houdini returned to downtown Cleveland to baffle Prospect Theater audiences. Boxing and wrestling matches also drew large crowds.

In 1908, when the B.F. Keith chain purchased the downtown Hippodrome Theater, the organization converted the Prospect into a short-lived playhouse specializing in movies. Travelogues and short comedies composed the greatest portion of the seventy-minute shows where tickets sold for five and ten cents. The Keith organization added vocalists to accompany the films, advertising the innovation as “Keith’s singing-living-selected pictures.”

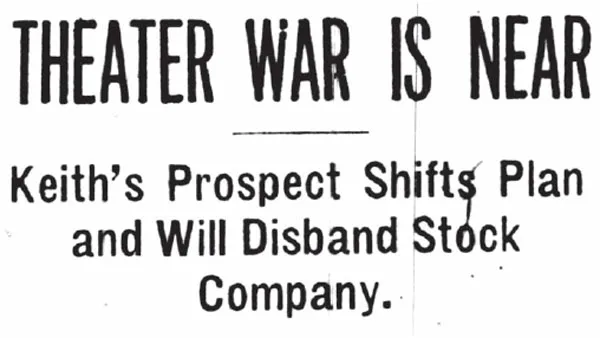

The Keith chain made a practice of suppressing its competition. In 1909, rumors persisted of the opening of a “small time” vaudeville theater on Euclid Avenue near Public Square. Although noted for operating “first-class” vaudeville houses, Keith nevertheless met the new threat by converting the Prospect into a “small-time” vaudeville venue with movies shown between live acts and all day on Sunday. A local theater critic described the offerings as “acts of less than headline caliber but of good quality.” Audiences enjoyed performances by mostly obscure singers, dancers and comedians along with trained cockatoos, gymnastic dogs and mechanical horses. Yet Prospect patrons did witness future star Will Rogers rope a horse on the theater stage. Keith even offered a novelty in its exhibition of movies. A “Daylight Motion Picture” apparatus allowed films to be shown with remarkable clarity in the well-lighted theater. The novel experiment became known as “daylight motion views.”

The Keith organization turned the Prospect Theater into a vaudeville house to suppress a potential rival. Courtesy of the Plain Dealer.

The novelty of movies added extra appeal to the live entertainment at the Prospect Theater, shown here in its vaudeville period. Courtesy of Cleveland Public Library, Photograph Collection.

By 1911, with the threat of a competitive theater crushed, live dramas evolved as the theater’s main attraction, with movies relegated to Saturdays and Sundays. But in 1917, the Prospect played an entire summer of feature-length movies and developed into a movie-only theater just before its closing in 1923. For more than three-quarters of a century, Clevelanders believed the playhouse had been totally demolished for commercial development. Yet in the first decade of the twenty-first century, construction workers peeled off lawyers of false fronts to expose the ceiling and a wall of the old theater.

While the Empire, Lyric and Prospect Theaters all closed in the 1920s, a few second-generation vaudeville venues, including the Hippodrome and Palace, transformed themselves into magnificent movie theaters.

![]()

Chapter 2

THE NICKELODEON ERA

In 1894, New Yorkers excitedly embraced the latest entertainment innovation, the Kinetoscope parlor. Placed inside attractive oak cabinets, Thomas Edison’s movie machines created an image of movement by using spools to revolve film. A coin dropped into a slot triggered an electric light to shine on the film. The machine projected the lighted image onto the end of the cabinet. Curious customers watched dancers, animals, boxing matches and other sights that emphasized motion, viewed through a peephole just large enough for the eye. The film show continued for about one minute, and the novelty of watching movies from machines survived for a mere six months.

Edison and his competitors correctly presumed customers would enjoy viewing movies projected onto large screens rather than watching films from a peephole. Since Edison considered movies no more than a quickly passing novelty, he balked at spending the small amount of money needed to adequately protect his movie machine and projection equipment through patents. As a result, the technology to project images onto screens progressed rapidly, as did the era of the nickelodeon.

Nickelodeons debuted in downtown Cleveland during the first decade of the twentieth century. The term “nickelodeon,” combining the five-cent admission price with the Greek word signifying an enclosed theater, denoted an early theater designed exclusively for movies. The nickelodeons did not employ coin-operated machines and, in fact, led to the machines’ obsolescence except in risqué settings.

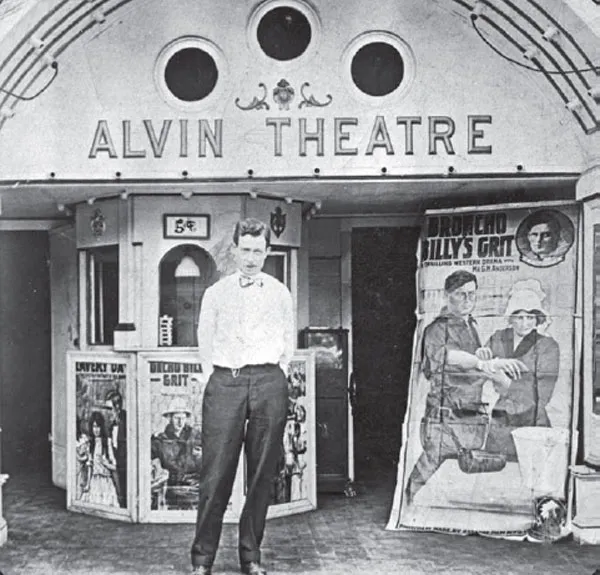

One of Cleveland’s first nickelodeons, the Alvin (shown here in 1913) survived as a movie theater into the late 1920s. Courtesy of Special Collections, Michael Schwartz Library, Cleveland State University.

Nickelodeons exhibited single-reel movies on screens (or sometimes bedsheets) that hung on back walls; added attractions incorporated lectures, slides and music played on phonographs. A singer, using hand-colored slides depicting a song’s lyrics, often plugged the latest popular melodies while the projectionist changed movie reels. A piano player usually provided accompaniment for the movies while audience members ate peanuts, tossing the shells on the floor. These primitive movie theaters all seemed to share one common characteristic: incredibly uncomfortable wooden seats, sometimes constructed from sawed-off telephone poles with planks nailed to the poles to create the backs of the chairs.

Three of Cleveland’s earliest nickelodeons evolved in a converted store on the corner of Superior Avenue and West Third Street, in the fifty-seat Alvin Theater on Ontario Street opposite the Sheriff Street Market and in the American Theater on Superior Avenue across from the current Federal Reserve Bank.

Alvin Theater patrons desiring a musical accompaniment to their film viewing reached through a hole in the theater’s wall and placed a nickel in an old Wurlitzer piano located in a next-door saloon. The music easily traversed the flimsy wall separating the beer parlor and theater. The Alvin’s owner eventually rented the saloon, knocked down the wall and greatly expanded...