![]()

1

Newburgh

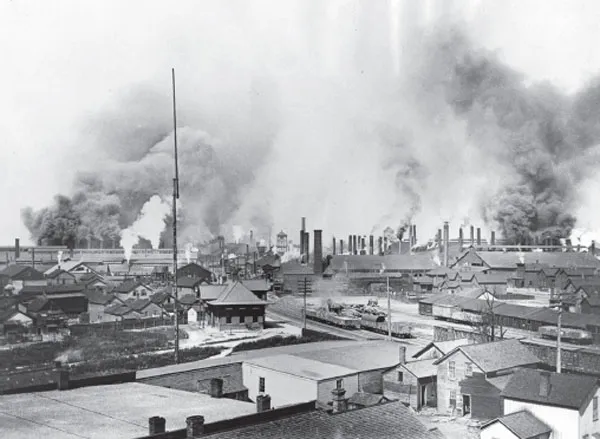

The Lure of the Steel Mills

John Pintar, the first known Slovenian visitor to Cleveland, arrived in 1879 but returned to his homeland after a stay of only five months. Four years later, he revisited the United States and soon migrated back to Cleveland. Unable to find suitable employment, he walked westward and, after thirty-three days, ended up in a Slovenian section of Pueblo, Colorado. With the prospects for finding work no better in the West, Pintar walked fourteen-hundred miles back to Cleveland, where he remained until his death more than three decades later.

In October 1881, Slovenian immigrant Joseph Turk survived an unusually long and arduous twenty-eight-day trip across the Atlantic Ocean. Speaking little English, Turk stepped off a train in Cleveland with no friends or relatives to assist him. He secured lodgings on Marble Avenue and found a job in a nearby shop that paid $1 for a ten-hour workday. By the end of one year, he had sent $100 back to his family in Slovenia.

Within two years, Turk had built a home on Marble Avenue, near the Newburgh steel mills where he now worked, and opened a prosperous saloon to serve as a meeting place for the thirty or so other Slovenians who had settled in the neighborhood. His daughter Gertrude joined him in 1885, becoming Cleveland’s first female Slovenian immigrant. By 1892, Turk had acquired a grocery store and three boarding homes. He presented the saloon to his daughter as a wedding gift and procured two more drinking establishments as presents for his sons.

In the late nineteenth century, the Newburgh Steel Mill provided employment for unskilled Slovenian immigrants. Courtesy of Cleveland Public Library, Photograph Collection.

Overly generous to newly arriving Slovenian immigrants, Turk lost his financial resources in an 1893 business downturn. For a time, he relied on the earnings of his two teenage sons. He eventually purchased land in Euclid, Ohio, where he grew grapes for making wine. He opened yet another saloon, this time in the Collinwood neighborhood.

John Bradac, who immigrated to Cleveland in 1890 at the age of twenty-two, resided in the Newburgh neighborhood for fifty-seven years. He opened saloons on Burke and Marble Avenues (about a block from each other) and aided more than eight hundred Slovenians in obtaining U.S. citizenship. Frank Kuznik arrived in Cleveland in 1900 and worked in the steel mills for five years before purchasing a tavern on East Eighty-First Street and a home above the tavern.

These and other saloons served as refuges where Slovenian immigrants, most unfamiliar with the English language and American customs, could share comradeship, debate politics, sing songs, play card games, participate in neighborhood gatherings and even obtain employment from factory foremen, who often recruited employees at the various saloons.

Drinking establishments enabled entrepreneurial Slovenians a straightforward entry into the business world if they agreed to sell beer manufactured by only one brewery. In exchange for this exclusive arrangement, the brewer provided essential expertise in composing property rental agreements, obtaining liquor licenses, securing bank financing and assisting in the training and paperwork required to acquire U.S. citizenship. With a multitude of brewers located in Cleveland, Slovenians experienced little difficulty in obtaining an obliging sponsor.

For Slovenian immigrants not interested in the business world, steady employment could be found in nearby factories, such as the American Steel and Wire Company, the Cleveland Rolling Mills and the Emma Furnace plant. John Horvath, settling in Cleveland in 1890, worked for American Steel and Wire for forty-one years. The plant employed Anton Gliha from 1900 to 1941 and Andrew Slack for decades following his 1898 arrival. Gliha died in his Aetna Road home above his own business, the Kozy Korner Tavern. Frank Strazar, the oldest of fourteen children, came to Cleveland in 1912 at the age of nineteen. After leaving his family’s Slovenian farm, he secured employment at the steel plant. Catering to immigrants’ love of music, the steel mill even organized a company band that presented concerts throughout the city.

With the advent of the automobile, the General Electric Company, located in the Hough neighborhood, also employed many Newburgh Slovenians. Eight to ten people would squeeze into an automobile to commute from the Broadway neighborhood. Immigrant John Strekal mastered the meat-cutting business as an employee of Swift and Company. Later, he and his wife, Mary, operated a grocery store and meat market for thirty years on East Eightieth Street. Mary lived her entire life above the store, as did her daughter, Mrs. Victor Matjasic.

Agnes Zagar, born on East 80th Street, moved one block east to make way for construction of the Slovenian National Home. During World War II, she worked at the Ohio Crankshaft Company on Harvard Avenue. Later employed by the Gottfried Clothing Company (located on Broadway Avenue at East 131st Street), she became a union steward and later chairman of the International Garment Workers Union. She served as a director of the Slovenian National Home for twenty-five years until she reached the age of eighty-five, four years prior to her death.

The approximate boundaries of this small Slovenian enclave were Union Avenue (north), Aetna Road (south), East Seventy-Eighth Street (west) and East Eighty-Second Street (east). Once farmland owned by Lorenzo Carter (Cleveland’s first settler) and his descendants, the Carter family sold the land for subdivision in the 1870s. Construction of homes began a decade later. To the west, Polish and Czech groups settled the neighborhoods between East Seventy-Eighth Street and Broadway Avenue. To the east, about ten sets of railroad tracks isolated East Eighty-Second Street from East Eighty-Eighth Street, the latter becoming part of a different neighborhood. The westernmost railroad track almost abutted the backs of the homes on East Eighty-Second Street. The tight fit allowed residents in their backyards to physically shake hands with the engineer of a passing train.

In the 1930s and ’40s, the close-knit community enjoyed summer picnics. At least one accordion player provided the accompaniment as picnickers sang old Slovenian songs and played baseball. Members of a teenage group made their own costumes for annual plays (mostly consisting of songs and jokes) staged at the local Slovenian Home. During the Depression, boarders occupied beds in most of the rooms of the houses except for the kitchen.

Along with neighborhood churches, Slovenian settlements constructed halls, usually called Slovenian National Homes. Functioning as meeting places and entertainment venues, these halls hosted local gatherings, political assemblies, boxing and wrestling matches, cultural programs and Friday evening fish fries. On October 19, 1919, the Newburgh neighborhood celebrated the laying of the cornerstone for the Newburgh Slovenian National Home, to be located on East Eightieth Street. The home opened the following June and, in 1949, expanded by adding still-existing bowling alleys and a large ballroom built to accommodate seven hundred persons.

The National Home is still in operation. Today, the basement area under the original meeting room is a barroom featuring a working jukebox and a non-operational wooden telephone booth. No ladies’ room exists in this part of the hall, since females were not allowed to enter the barroom when the facility first opened. Today, the National Home is a venue for weddings, comedy shows, fish fries, clambakes, Browns and Cavaliers watch parties and even a performance by members of the Cleveland Orchestra.

On the other side of the railroad tracks, the Slovenian Labor Auditorium on Prince Avenue also staged cultural events and wedding receptions and served as a public meeting place. The Socialist Party of America used the auditorium for its 1922 national convention. In the 1930s, the facility hosted meetings of the Russian Democratic Club. In 1932, three pistol shots interrupted the music of an accordion band entertaining at a Slovenian society dance. Twenty-one-year-old Carl Napoli had confronted Joseph Kravas (age forty-four) regarding Joseph’s advances toward the mother of Carl’s eighteen-year-old wife. As a fistfight continued, Carl, believing Joseph had pulled a knife, shot Joseph three times, once in the hip and twice in the arm. Extensively remodeled in 1949, the labor auditorium is now the home of the New Galilee Baptist Church.

The neighborhood supported grocery stores, meat markets, a barbershop and a tailor shop. Trucks containing milk, ice, produce, baked goods, fish and waffles made periodic visits to the community. A grandmother, who spoke no English and never left the neighborhood, explained to her grandchildren that she had everything she needed right in the community—her church, a grocery store, a butcher shop and a funeral home.

Three generations of the Perko family lived above their grocery store, which incorporated a smokehouse in the backyard. During the Depression, the family offered credit, sometimes extending for years, to struggling neighbors. In the 1950s, an A&P supermarket debuted on Broadway Avenue, but it acquired little business from Slovenians, who remained loyal to the Perko family, who had helped them survive the Depression.

Mathew Sirk’s store on East Eighty-Second Street, later owned by Frank Sirk, offered an amazing array of merchandise, including penny candy, ice cream, beer and liquor. It also had one solitary bowling alley.

After his barbershop closed for the day, Anthony (Bill) Strainer traveled to the homes of executives to supply evening haircuts for managers who had little time during working hours. Beginning in the 1920s and until the mid-1960s, Strainer operated his shop on East Eightieth Street. The site is now a parking lot for the Newburgh Slovenian Home.

Following World War II, Edward J. Zabak and his brothers organized a polka band. For more than forty-three years, Edward also owned Zabak’s Tavern, located on Union Avenue at East Seventy-Eighth Street. The tavern’s small stage sometimes accommodated multiple bands participating in impromptu polka jam sessions. Patrons desiring to dance maneuvered around a tiny dance floor, artfully learning how to step around each other without creating a crash. Zabak’s children, sleeping in a bedroom directly above the dance floor, closed their eyes nearly every night listening to polka music seeping up through the floor.

From the 1920s into the 1960s, adventurous Newburgh residents traveled north down Broadway Avenue to partake in additional shopping, grocery and banking alternatives. Some residents walked as far as East Fifty-Fifth Street, whose intersection with Broadway Avenue comprised a thriving retail district. At times, these jaunts included a visit to one of four movie theaters along the route—the Market Square, Grand, New Broadway and Olympia. To the east, the Union and Union Square movie houses presented even more options.

A few creative neighborhood teenage boys developed their own forms of entertainment. One of the more unusual escapades involved the use of railroad “dynamite caps.” Railroad companies placed these two-inch-square caps on tracks to warn engineers that another train had stopped in an unexpected place. The loud noise created by a cap would alert the engineer to slow down and exercise extreme caution. Raiding a parked caboose used to store the caps, the Slovenian urchins would steal the noisemakers and place them on Broadway Avenue streetcar tracks. In addition to creating an earsplitting clamor, the caps at times knocked the streetcars right off their tracks. Another imaginative prank involved filling old, unwanted purses with human feces. The boys would throw the purses on Broadway Avenue and enjoy the surprise when a passerby retrieved the purse by placing his hand in it.

Counterbalancing the mischievous boys, a few Slovenian girls mastered the art of creating exquisite bobbin lace, a tradition learned at an early age in Slovenia. The artistic work at times produced family heirlooms, such clothing used at baptismal and confirmation ceremonies and as decorations on a ring bearer’s pillow. The lace also beautified folk costumes and liturgical dress.

In the early 1970s, the Newburgh neighborhood exhibited its first outward signs of decline—the closing of the St. Lawrence Church School. The Slovenian presence markedly deteriorated in the ensuing decades. Today, the still-open National Home and the former St. Lawrence Church are among the few visible reminders of Cleveland’s first Slovenian neighborhood.

![]()

2

St. Lawrence Church

Newburgh’s Slovenian Foundation

Most Newburgh Slovenians initially celebrated mass in the basement of the nearby Holy Name Catholic Church (located on Broadway Avenue near Harvard Avenue), but the immigrants never felt comfortable in the predominately Irish church. A few, yearning to worship in an established Slovenian church, endured a reasonably long jaunt to St. Vitus near St. Clair Avenue. Finally, on May 11, 1902, more than three thousand mostly Slovenian individuals celebrated the cornerstone-laying ceremony for St. Lawrence Catholic Church and its affiliated school, both to be located on East Eightieth Street in the heart of Newburgh’s Slovenian community. Three bands provided the musical entertainment for the joyful occasion. Bishop Jacob Trobec of St. Cloud, Minnesota (America’s only Slovenian bishop at the time), delivered the principal speech. The new church began with about eight hundred members.

The quickly built, two-story, brick Romanesque building combined a school on one floor and a place of worship on the other. Reverend Francis Kerze, the church’s first priest, had previously been an assistant pastor at St. Vitus Church. Along with delivering spiritual messages, Kerze dealt with numerous issues involving both the church’s parishioners and the community. In 1905, when Cleveland examined the impact of railroad train smoke, the city appointed Kerze as a special deputy inspector to report, on a daily basis, the conditions around the church, school and neighborhood.

On several occasions, when ill feelings arose between differing factions of the church, malcontents stoned Kerze’s home. One evening, an unusually unruly crowd broke a window in the rectory. The priest pulled out a revolver and fired a shot, allegedly to frighten the rowdies away. Police arrested Kerze on a charge of shooting with intent to wound, but the case was quickly dismissed. Following Kerze’s seven-year tenure at St. Lawrence, Reverend Joseph Lavric served as pastor until 1915. The next priest led the church for forty-seven years.

In the 1870s, Simon Oman emigrated from Slovenia to Brockway Township, Minnesota, one of North America’s oldest Slovenian settlements. On May 22, 1879, Simon and his wife welcomed John J. Oman into the world, the second of their eleven children. John gave up school in the fifth grade to work on his parents’ farm. After later toiling as a water boy at a locomotive plant and as a lumberjack, fireman and miner, he entered a Minnesota seminary.

In 1912, a year after his ordainment, Reverend Oman reluctantly departed the picturesque Brockway setting for an assignment at Cleveland’s St. Vitus Church. Three years later, the young, American-born priest, who lacked a good command of the Slovenian language, became head pastor at St. Lawrence. Any initial misgivings on the parishioners’ part seemed to quickly evaporate. Oman taught the congregation enough English for them to pass citizenship examinations and stressed teaching the Slovenian language in the church school. Following his 1962 retirement, Oman returned to Brockway. When he died four years later, his funeral mass took place in the same church where he had been baptized.

Between 1910 and 1920, church membership doubled from 1,500 to 3,000 worshipers. In 1924, construction began on a new church; by the end of the 1920s, 4,413 people attended services at St. Lawrence. Yet the church remained unfinished. Fundraising, always difficult in the poor congregation, became virtually impossible during the Depression. In the meantime, parishi...