- 128 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Hidden History of East Texas

About this book

The heritage of East Texas partakes in the same degree of unexpected turns and hidden depths as its backroads and bayous. One line of inquiry meanders into another. Start out searching for La Salle's grave and end up chasing Spanish gold in Upshur County. From Sam Houston's Bible to the Longview nightclub that hosted both Frank Sinatra and Elvis Presley, one tale follows another and introduces a cast of characters that includes Candace and Peter Ellis Bean, Old Rip, Jack Lummus and Vernon Wayne Howell. Part the Pine Curtain with Tex Midkiff for a history as heated as the La Grange Chicken Ranch's parlor and irresistible as a batch of Golden sweet potatoes.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Hidden History of East Texas by Tex Midkiff in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & North American History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

PART I

BEFORE 1850

ANCIENT TEXANS

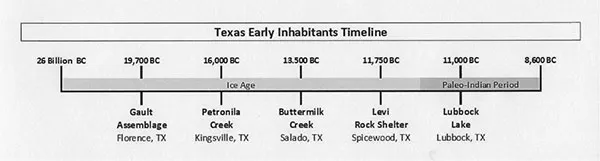

Everybody loves East Texas—even the people who were evading the vast glacial thaws and pushing animals of all kinds south some twenty-one thousand years ago. The earliest people who lived in what we now call Texas showed up during the later stages of the ice age. Scientists can identify them by the kinds of weapons they made for hunting. Archaeologists have found this evidence by looking at several types of sites, including campsites, where people lived; quarries, where people cut away material to use as tools; kill sites, with evidence of hunters and the remains of their prey; and cave painting sites.

Gault Assemblage of Tools, 19,700 BC

As recently as July 2018, a research team led by Thomas Williams from the Department of Anthropology at Texas State University, working at the Gault Site near Florence, northwest of Austin, dated a significant assemblage of stone artifacts to sixteen thousand to twenty thousand years of age, pushing back the timeline of the first human inhabitants of North America. Williams’s team of archaeologists excavated the Texas bedrock and uncovered ancient rocks shaped into bifaces—used as hand axes—blades, projectile points, engraving tools and scrapers. They refer to the tools as the Gault Assemblage.

Gault archaeological excavation site in East Texas. Wikimedia Commons.

Author’s graphic.

According to Science News, “the team used optically stimulated luminescence to age the materials, which means they were able to find how long it had been since the sediment the items were found in had been exposed to sunlight.” Not much about the physical traits of the people who used the tools can be determined from the material in the find, but its significance lies in how old the items are. The team does not claim to have answered the question, “Who were the first Americans?” But the find illustrates the presence of a heretofore unknown “projectile point technology” in North America long before any previously dated sites.

Petronila Creek Mammoth Bones, 16,000 BC

Humans were occupying a hunting and fishing camp on Petronila Creek, between Kingsville and Corpus Christi, eighteen thousand years ago. They were hunting for mammoth, ground sloth, camel, horse, peccary, antelope, coyote, prairie dog and alligator, as well as fishing for catfish, gar and other fish.

A “bone bed” was found at this site that contained some of the largest mammoth femurs (1,429mm/400mm) ever found in North America and included “cut marks” from sharp stone tools. The Petronila Creek site was important at the time because it preceded the advent of the “Clovis” culture by seven thousand years.

Buttermilk Creek Hunter-Gatherers, 13,500 BC

On March 25, 2011, along with colleagues, archaeologist Michael R. Waters, director of the Center for the Study of the First Americans at Texas A&M University, reported that excavations at the Buttermilk Creek Complex at the Debra L. Friedkin Paleo-Indian archaeological site in present-day Salado showed that hunter-gatherers were living at this site and making projectile points, blades, choppers and other tools from local chert for a long time, possibly as early as 15,500 years ago.

More than fifteen thousand artifacts were embedded in thick clay sediments immediately beneath typical “Clovis” material. These discoveries predated the arrival of the Clovis people from Asia and confirm the emerging view that people occupied the Americas long before what scientists had previously determined.

Levi Rock Shelter, 11,750 BC

The Levi Rock Shelter, named for former property owner Malcolm Levi, is an archaeological site near Spicewood in western Travis County. Located along Lick Creek, the site was excavated on three occasions (1959–60, 1974 and 1977) under the direction of Herbert L. Alexander Jr. He collected considerable evidence of the use of this shelter in pre-Paleo-Indian times. A travertine deposit containing bone and flakes against the back wall is apparently the oldest deposit in the shelter.

A sparse lithic assemblage and bones of deer, rabbit, bison, dire wolf, horse and other species were recovered. This site also contained bones of extinct animals, including bison, peccary and tapir. Alexander is credited with discovering the “Levi Point” (also known as Plainview-Angostura arrowheads). Two types were found at this site. One was a lanceolate form, and the other was a constricted stem point. Both points were thought to be made by the same localized group.

Lubbock Lake Bison Bones, 11,000 BC

Apparently, an ancient tribe with no sense of direction missed East Texas and wandered over to the next watering hole! In 1936, the City of Lubbock dredged the meander of the Yellow House Draw, also known as “Punta de Agua,” a tributary of the Brazos River, to make it a usable water supply. These efforts were unsuccessful but brought to light the archaeological significance of the site. The first explorations of the site were conducted in 1939 by the West Texas Museum, now the Museum of Texas Tech University. In the late 1940s, several bison kills were discovered. These charred bison bones produced the first-ever radiocarbon date.

Like at all these archaeological sites in Texas, the smallest artifact can be a crucial clue to unraveling a “day in the life” of an ancient Texan—a bison kill, an overnight camp, a projectile point providing a meal—sealed by the almost unbroken deposition of windborne dust, overbank flood mud or pond and marsh deposits.

It is comforting to think that the oldest inhabitants of North America chose East Texas to make their homes. Contrary to popular belief, the oldest Texans are not those guys surrounding the “Table of Knowledge” at the Yantis Café each morning.

A FRENCH WHODUNIT AND A TEXAS WHEREWASIT

MYSTERY OF THE EXPLORER LA SALLE’S LAST RESTING PLACE

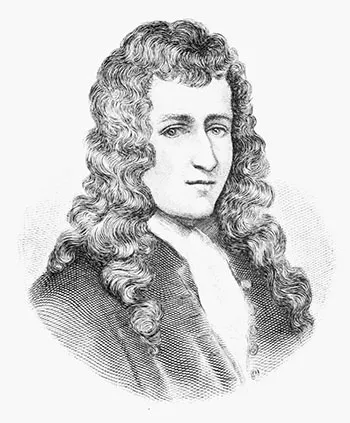

In the tenth or eleventh grade, while studying European exploration of the New World, you probably came across the French explorer René-Robert Cavelier, Sieur de La Salle. If your memory is somewhat available from that period when you passed notes in study hall and stuck chewing gum to the bottom of your desk, then you might recall that he was on an expedition in Texas when someone killed him and disposed of his body. To this day, history has fallen a little short on the “whodunit” or the “wherewasit.” The fact that La Salle’s death occurred in 1687, before satellite imaging and GPS positioning, not to mention the television show Expedition Unknown, contributes to the mystery.

What we do know is that on July 24, 1684, La Salle set out for North America with a large contingent of four ships and three hundred sailors to establish a French colony on the Gulf of Mexico at the mouth of the Mississippi River and challenge Spanish rule in Mexico.

The expedition was doomed from the very beginning. La Salle argued with the marine commander over navigation. Pirates took one of his ships in the West Indies. When the fleet landed at Matagorda Bay (near present-day Port O’Connor), they were five hundred miles west of their intended destination. There, a second ship sunk and a third headed back to France. A drunken pilot wrecked the last ship, stranding the remaining crew on land. In October of that year, La Salle took a small contingent of men and headed up the Lavaca River, trying to locate the Mississippi. After most of his men were lost, he continued with about thirty men until a mutiny erupted.

Nineteenth-century portrait of René-Robert Cavelier, Sieur de La Salle. Wikimedia Commons.

On March 19, 1687, he was slain by one of his own men during an ambush. According to a written account of one of the survivors, they were “six leagues” from the westernmost village of the Hasinai (Tejas) Indians. Historians differ on which of his men pulled the trigger on La Salle, but the preponderance of the evidence rests with Pierre Duhaut, aided by Jean L’Archevêque.

This may have been the first known murder of a Caucasian male in East Texas, but the lasting mystery continues to be a Texas “wherewasit.” At least eight communities in Texas have made claims as “the place where La Salle was killed.”

Alto, Texas

An area near the town of Alto is one of the contenders for this debatable honor. The late F.W. Cole, a Cherokee County historian, did considerable research of La Salle’s movements in East Texas. He concluded that La Salle was killed on the east bank of Bowles Creek in the Martin Lacy Survey two and a half miles southeast of Alto.

In an article originally published in the Rusk Cherokeean and later printed in Two Hundred and Fifty Years: History of Alto, Texas, 1686–1936, Cole contended that La Salle could not have been killed near Navasota but was instead murdered somewhere near the Neches River. His thorough inspection of French records shows that La Salle’s expedition crossed the Colorado River on January 27, the Brazos River on February 9, the Trinity River on March 6 and the Neches River on March 14, 1687. Cole placed the murder site as two to three leagues (a league being about three miles) northeast of the point where La Salle crossed the Neches, or just south of what was once Harrison’s Branch, in the Martin Lacey Survey in Cherokee County.

Beaumont, Texas Country Club

Another claim to the historic murder site has been made by the Weiss family of Beaumont. What makes this claim unusual is that the family places La Salle’s death at the current location of the Beaumont County Club. A few historians have asserted that the murder took place at “a crossing about fifty miles up the Neches river,” and the Beaumont Country Club would fit this description.

The arguments for this site revolve around the “excellent camping grounds” and “high banks affording safe landing,” plus the fact that the Beaumont Country Club marks an ancient crossing of the Neches long known as Collier’s Ferry. As you stroll up the eighteenth fairway, you may be walking in the shadow of what the French courtiers called the “Adventurer.”

Burkeville, Texas

In 1913, Jasper native Jesse J. Lee wrote a letter to a friend at the University of Texas claiming that a camp of German stave makers (whiskey barrel parts) cut down a large white oak tree near Burkeville, in Newton County, Texas, and found carved in its trunk the words “La Salle.” This led to local speculation that La Salle may have been killed near the Sabine River. This historic crossing, which is now called Burr’s Ferry Bridge, is where LA 8 meets Texas State Highway 63 at the Louisiana and Texas state line between Burkeville, Texas, and Burr Ferry, Louisiana.

Hainesville, Texas

This community became famous as a possible burial site in 1870, when excavations were being made for the Haines mill. Ditch diggers uncovered some twenty-five old rifles and later the unmarked grave of a white man interred in a hewn-log coffin near the Joe Moody farm. Speculation had it that the body was that of the French explorer La Salle. Another theory advanced in the 1950s suggested that the remains were those of a member of the Moscoso expedition. Because of the lack of conclusive evidence, both legends have been generally discounted. Further research suggests that the rifles dated from the 1700s and not the 1500s, as previously believed.

Navasota, Texas

One of the most convincing claims to the French explorer’s killing field is from Navasota. So certain of their historical assertion, the Texas Society of the Daughters of the American Revolution and the townsfolk of Navasota erected a local statue to the memory of La Salle in 1930. Their claim is strongly supported by a book, The La Salle Expedition to Texas: The Journal of Henry Joutel, 1684–1687, edited by William C. Foster. Included in the book is a map indicating that La Salle was ambushed somewhere in western Grimes County, about twelve miles west of Navasota. The expedition crossed the Brazos River on March 14, 1687, and he was killed five days later north of the crossing, according to this account.

Pine Island Cemetery in Vidor, Texas

This is the only cemetery that claims to be the burial site of the famous adventurer. The cemetery isn’t located on an island. It was so named because its boundaries fell within a stand of pine trees that grew in the middle of an open prairie, like an island. Just off Mansfield Ferry Road in Vidor, about three-quarters of a mile south of FM 105, the overgrown cemetery is a visual aid to the legend of the French whodunit.

In an interview for an Orange County Historical Society publication in 1976, Marion Stephenson of Vidor said that his grandmother Martha Day Stephenson, who was an Alabama Indian, told him that La Salle and six of his men were buried at the Pine Island Cemetery. Apparently, this was based on stories handed down in her family from generation to generation.

Credibility of the Stephenson family story is supported by an 1897 book by M.E.M. Davis, The Story of Texas Under Six Flags. According to Davis, one of La Salle’s men, Moragnet (his nephew), had been on bad terms with two others, Jean L’Archevêque and Pierre Duhaut, when they camped “near the crossing of the Neches River.” These two murdered Moragnet and an Indian hunter named Nika while they slept. When La Salle went looking for his nephew, they fatally shot him in the head. Davis wrote about La Sa...

Table of contents

- Front Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Contents

- Acknowledgements

- Introduction

- PART I: BEFORE 1850

- PART II: 1850–1900

- PART III: 1900–1950

- PART IV: SINCE 1950

- About the Author