- 208 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

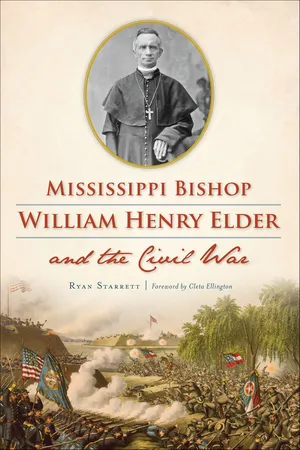

Mississippi Bishop William Henry Elder and the Civil War

About this book

Conquest. War. Famine. Death. During the Civil War, all Four Horsemen circled the flock of William Henry Elder, the third bishop of Natchez. Elder was a hopeful unionist turned secessionist whose diocese encompassed the entirety of Mississippi. Consequently, he witnessed many of the pivotal moments of the Civil War-the capitulation of Natchez, the Siege of Vicksburg, the destruction of Jackson and the overall desolation of a state. And in the midst of the conflict, Bishop Elder went about his daily duties of baptizing, teaching, praying, preaching, performing marriages, confirming, comforting and burying the dead. Join author Ryan Starrett on this moving account of Elder and the heroics of this wartime bishop.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Mississippi Bishop William Henry Elder and the Civil War by Ryan Starrett in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & American Civil War History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

THE APPOINTMENT

On May 3, 1857, in his home state of Maryland, William Henry Elder received his marching orders. On the same day he was appointed to take charge of the fledgling diocese of Natchez, Mississippi, he was ordained its bishop. The next twenty-two years of his life would be full of romance and joy, progress and war, sickness and destruction, ruin and reconstruction. Natchez was both the vocation and the cross for William Henry Elder.

Natchez, the city that would become Elder’s home for more than twenty-two years, already had an established reputation when he arrived. It was known both for its opulence and its violence. It was home to the dregs of the Mississippi River traffic and to some of the richest men in the nation. It harbored and nurtured scoundrels and serial killers at the same time it was home to a who’s who of United States culture. James Burr, John Murrell, James Audubon, Andrew Jackson and scores of other villains and icons had wandered its streets.

Despite the wealth and history of Natchez, the Mississippi legislature voted to move the state capital to a more centralized location, and the administrative center of the state moved ninety miles east, to Jackson, in 1822. Yet Natchez remained the episcopal see, the headquarters, of the Catholic presence in Mississippi.

Andrew Jackson. Library of Congress.

John James Audubon in the 1820s. Library of Congress.

John Murrell, based on a print. Cincinnati Digital Library.

A large diocese (in terms of land), a spread-out population and a see that was no longer the capital of the state meant that Elder would be on the road—something that didn’t bother the young and energetic bishop.

The thirty-seven-year-old bishop arrived at his see on May 30, 1857, with “soft breezes blowing across the Mississippi River.” He was the only native-born cleric in his entire diocese. Seven of his priests came from France, three from Ireland, one from Belgium and one from Saxony (in present-day Germany). In fact, Elder inherited about as many priests as siblings he had left behind in Maryland. He had grown up in a household with six brothers, three sisters and two or three orphans living under the same roof. Now, he had a dozen clerics responsible for the salvation of an entire state.1

A young William Henry Elder. Archives of the Diocese of Jackson.

One of his first acts as bishop was to appoint Father Mathurin Grignon as his vicar general, or representative. This would allow Elder to immediately travel the entirety of his extensive diocese. The odyssey would both familiarize him with his new home and introduce himself to his flock, both religious and lay.2

Elder completed his marathon inspection of the diocese and learned several significant facts. The Catholics of Mississippi formed a microcosm of the state. They stood upon all rungs of the economic and social ladder, from slave to subsistence farmer to professor to state legislator. Just about the time Elder assumed his see, large numbers of Irish people migrated to the state and took jobs as railroad and levee workers. Of the ten thousand Catholics in the diocese—7 percent of the population of Mississippi—one thousand were slaves. In all, Elder had eleven parishes with eleven churches and twenty-eight mission stations, and only a dozen priests to tend them. It was destined to be a busy two decades for the energetic bishop.

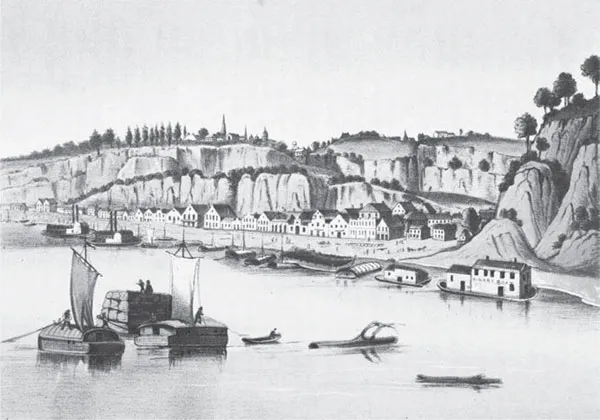

Natchez in the 1850s—the Bluff and Under-the Hill are both clearly visible. The Beinecke Library at Yale University.

Elms Court, Natchez, Mississippi—residence of the Honorable A.P. Merrill, 1850s. Metropolitan Museum of Art.

A ship at rest beneath one of the Natchez Bluffs in 1864. Library of Congress.

The biggest challenge to Elder’s episcopacy was the threat of a looming civil war. It was not the first time the horrors of a fraternal war threatened the unity of his homeland. A significant number of New Englanders had threatened secession in the midst of the War of 1812. Large numbers of Westerners made similar threats to join the ambiguous Burr-Wilkinson alliance that, if successful, might have sundered the West from the infant nation. John C. Calhoun imperiled the Union with constant rhetoric involving state’s rights and nullification. Now, a new brand of fire-eaters promised secession if the institution of slavery was not protected and extended.

From his installation in 1857 to the presidential election in 1860, Elder remained on the sidelines, as did nearly every American bishop. The ecclesiastical provinces of Baltimore and Cincinnati summarized the Catholic position regarding the role of the clergy in the secession debate. The former stated: “Our clergy have wisely abstained from all interference with the judgement of the faithful, which should be free on all questions of polity and social order, within the limits of the doctrines of Christ.”3 The latter proclaimed: “While the Church’s ministers rightfully feel a deep and abiding interest in all that concerns the welfare of the country, they do not think it their province to enter into the political arena.”4 Bishop Elder adopted the same stance. Neither he nor his priests promoted nor condemned secession. That was a matter for the laity (nonclergy) to decide.

Although he kept his thoughts to himself, Elder prayed for peace. If secession could occur peacefully, so be it. If not, then war was always a great evil—necessary sometimes, as his church’s just war theory set forth,5 but always ugly and vile and to be avoided at nearly all costs. War interrupted the day-to-day business of saving souls. It introduced chaos into the public order, and it imposed upon churches, schools and charitable institutions.6 Not to mention, it frequently demonized the enemy and dehumanized the soldiers of one’s own side.

Finally, Elder’s desire for peace would have been strengthened by the fact that both Natchez and Vicksburg—the two Mississippi cities with the largest concentrations of Catholics—were full of hopeful Unionists. They were wealthy cities with politically powerful merchants who relied upon the cotton trade and an open Mississippi River. War, or even the threat of war, would endanger their pocketbooks. Thus, Elder, though in an ardent secessionist diocese, spent the majority of his days leading up to 1860 surrounded by Southern Union men.7

In the weeks leading up to the secession convention, Elder sent a circular letter to his priests instructing them to offer prayers and Masses that the legislators would receive heavenly wisdom before the upcoming convention. He also implemented a diocesan-wide fast for each Friday of Advent.8 Unlike many of his Protestant counterparts, Elder didn’t tell his priests to urge their flocks to vote one way or another. He simply prayed that the legislators would vote the right way. What that “right” way was, Elder never mentioned publicly—if he even knew himself.9

Ultimately, Elder’s handling of the secession question can be summed up in a letter he wrote to his cobishop and friend Francis Kenrick, of Baltimore, Maryland:

My course, & I believe the course of my clergy, has been not to recommend secession—but to explain to those who might enquire, that—if they were satisfied, dispassionately—that secession was the only practical remedy, the only means of safety—their religion did not forbid them to advocate it—on the contrary they were bound to do, what they believed the safety of the community required.10

Some of Elder’s flock sided with the Unionists, some with the secessionists. The latter garnered the necessary votes, and Mississippi officially seceded from the United States on January 9, 1861. Once it was clear that a new state government—and, on March 29, 1861, a functioning Confederate government—would be established, Elder urged his flock to support the new authority. He wrote a letter to the bishop of Chicago, James Duggan, explaining his decision to stand by the new Confederate States of America:

I hold it is the duty of all Catholics in the seceeding [sic] states to adhere to the actual government without reference to the right or the wisdom of making the separation—or to the grounds for it:—our State governments & our new Confederation are de facto our only existing government here, & it seems to me that as good Citizens we are bound not only—to acquiesce to it—but to support it, & contribute means & arms.11

Shortly after, Elder wrote to Bishop Kenrick:

Since secession has been accomplished—I have advised even those who thought it unwise—still to support our State Govt. & the new Confederacy—as being the only Govts. which exist here de facto. I have encouraged all to give a hearty support—to enrol [sic] as soldiers—to go forward with their taxes—to co-operate in any way they had occasion for.12

For better or worse, the Confederate States provided the functioning government of Mississippi. Right or wro...

Table of contents

- Front Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Dedication

- Contents

- Foreword, by Cleta Ellington

- Preface

- Acknowledgements

- Introduction

- 1. The Appointment

- 2. The Soldier-Sheep

- 3. The Ghosts of Battle

- 4. October 28 to November 16, 1862

- 5. Flashback: Childhood and Parents

- 6. November 19, 1862, to February 23, 1863

- 7. The Queen of the West

- 8. February 25 to July 6, 1863

- 9. Meanwhile…in Vicksburg

- 10. July 7 to July 20, 1863

- 11. St. Peter’s Becomes a Relic of “Chimneyville”

- 12. July 20 to July 24, 1863

- 13. The Battle

- 14. July 24 to September 16, 1863

- 15. The Hospitals

- 16. September 17 to October 25, 1863

- 17. December 22, 1863, to June 25, 1864

- 18. June 26 to August 13, 1864

- 19. August 14 to December 27, 1864

- 20. The Occupation

- 21. December 27, 1864, to March 27, 1865

- Conclusion

- Notes

- Works Cited

- About the Author