- 128 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Hidden History of Helena, Montana

About this book

Distinguished by statesmen and magnates, Helena's history is colored with many other compelling characters and episodes nearly lost to time. Before achieving eminence in Deadwood, Sheriff Seth Bullock oversaw Montana Territory's first two legal hangings. The Seven Mile House was an oasis of vice for the parched, weary travelers entering the valley on the Benton Road, despite a tumultuous succession of ownership. The heritage of the Sieban Ranch and the saga of "King Kong" Clayton, "the Joe Louis of the Mat," faded from public memory. From unraveling the myths of Chinatown to detailing the lives of red-light businesswomen and the Canyon Ferry flying saucer hoax, revered local historians Ellen Baumler and Jon Axline team up to preserve a compendium of Helena's yesteryear.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Hidden History of Helena, Montana by Ellen Baumler,Jon Axline in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & North American History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

GETTING HERE FROM THERE

Helena and the Benton Road

By Jon Axline

Transportation was a big deal for the Montana mining camps, and for Helena it was no different. During its mining camp phase, the Queen City was fortunate to be at the hub of several major arterials and a network of smaller feeder roads that led to other mining camps in the area. A good road was the lifeblood of any community, but this is especially so for a remote mining camp in the wilds of the northern Rocky Mountains. From Helena roads radiated to Butte, Virginia City, Deer Lodge, Confederate Gulch and the Gallatin Valley. Perhaps the most important of all the roads was Benton Road between Helena and the steamboat port of Fort Benton.

During the summer of 1805, William Clark noted an abundance of aboriginal trails north of the Helena Valley. The valley, even then, was a crossroads for Montana’s first citizens as they followed the bison herds in their annual migrations. In 1853, the federal government commissioned an extensive survey of the northern Rocky Mountains and the Pacific Northwest for potential routes for a northern transcontinental railroad. Through much of the 1850s, exploring parties crisscrossed the region in search of a good route for the steel rails. The most prominent of these explorers was a recent West Point graduate and lieutenant in the U.S. Corps of Topographical Engineers, John Mullan.

A firm believer in the railroad as a symbol of civilization, he was committed to finding the best way across the mountains for the proposed line. But he also concluded that a good military wagon road should precede the railroad. To that end, he and his boss, Washington territorial governor Isaac Stevens, convinced Congress to fund the construction of a wagon road from Walla Walla, Washington, across the Rockies to Fort Benton—the world’s innermost steamboat port. Mullan and 230 laborers and soldiers began the task of building the 624-mile wagon road in 1859. The road, which followed old Indian trails, skirted the Helena Valley in 1860. Mullan, clearly optimistic about the valley’s potential, described the valley in 1865 as containing “several small and choice localities for farms….I look forward with much hope to see all these creeks settled and fine farms developed under the hand of the Rocky Mountain farmer.” He completed the road on August 1, 1860. The first engineered and the first federally funded road in the Treasure State, Mullan Road became the core of the territory’s road network and, later, the modern highway system in western Montana.

Gold strikes on Grasshopper Creek in the summer of 1862 brought the first large numbers of Euro-Americans to the remote northern Rockies. Mullan Road was an important thoroughfare for pilgrims and supplies destined for the mining camps. Members of the Fisk Expeditions in 1862 and 1863 followed a northern overland route to Fort Benton and then navigated the road south over Mullan Pass to the gold camps. The pass west of Helena was a busy place in the early 1860s, and Mullan Road ruts still scar the meadow on top of the Continental Divide. The discovery of gold placers on Last Chance Creek in July 1864, though, changed the character and, eventually, the name of the road.

The rich gold strike on Last Chance Gulch drew hundreds of miners, businessmen and others to the Helena Valley. By the end of the year, freighters had blazed a trail from Mullan Road to Helena. Benton Road, as it became known, provided a significant lifeline to the settlement, enabling the importation of supplies critical to the survival and prosperity of the mining camp. It also facilitated the shipment of gold and other minerals back to the United States. The 130-mile route was well marked and easy to follow with stage stations located about every ten to fifteen miles along its length.

The first Benton Road configuration branched off Mullan Road at the Austin junction and followed Birdseye Road, Country Club Avenue and Euclid Avenue into Helena. It was the primary arterial into Helena from Fort Benton from 1864 until 1868, when the freighters blazed a new alignment. For a time, Andrew Glass operated a small stage stop and saloon, near where the road crossed Seven Mile Creek. Today, a collection of outbuildings and the remains of a false-fronted commercial establishment still stand at the site.

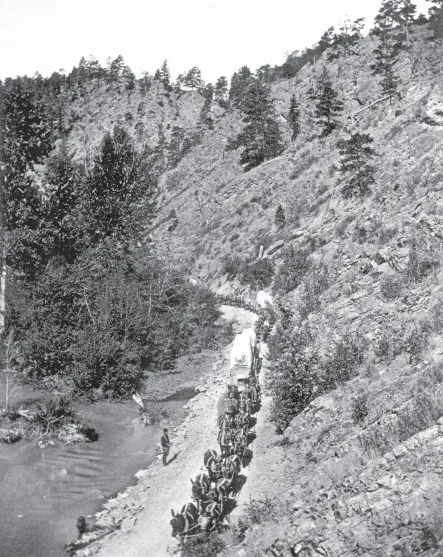

Hugh Kirkendall’s mule-drawn freight wagons were a common sight on Benton Road during the 1860s and 1870s. From MHS Photograph Archives, Helena, Stereograph Collection.

By 1868, heavy traffic on the road led to the establishment of a second branch road to Helena from Benton Road. From Silver City, it mostly followed today’s Lincoln Road and curved into the valley from the Scratch Gravel Hills. Once in the valley, Benton Road followed two routes to the city: one along today’s Green Meadow Drive to Euclid Avenue and the other along the general alignment of North Montana Avenue. This alignment came into Helena via Gold Avenue and North Last Chance Gulch. This route eventually superseded the original Benton Road alignment to Helena and was the primary arterial into the city until the completion of the Northern Pacific Railway in 1883. Because the new road lacked the steep grades of its predecessor, it was easier for the heavy freight wagons to negotiate.

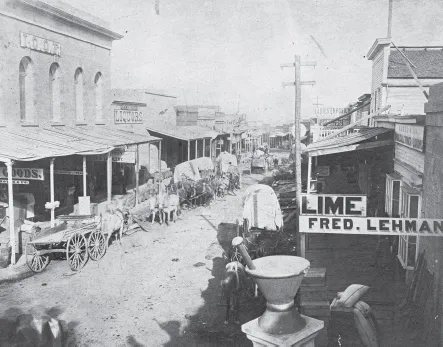

Freighters had to wait their turn to deliver supplies in narrow Last Chance Gulch. From MHS Photograph Archives, Helena, 954–200.

In the late summer months, an observer on the edge of town would have seen the freighters coming this way long before they ever saw a wagon or heard a bullwhacker cursing at his charges. Like many well-traveled roads at the time, Benton Road was not limited to a single track. During the summer months, the dust on the heavily used route, combined with the shortage of grass for the horses, mules and oxen, would have caused the wagons to fan out. The road cut a wide swath across the Prickly Pear and Little Prickly Pear Valleys as it neared Helena. Ten Mile Creek got its name because it was ten miles from Silver City—the valley’s first population center before the gold strike on Last Chance Gulch. Creek crossings provided mile markers of sorts for the freighters and coachmen who used the road.

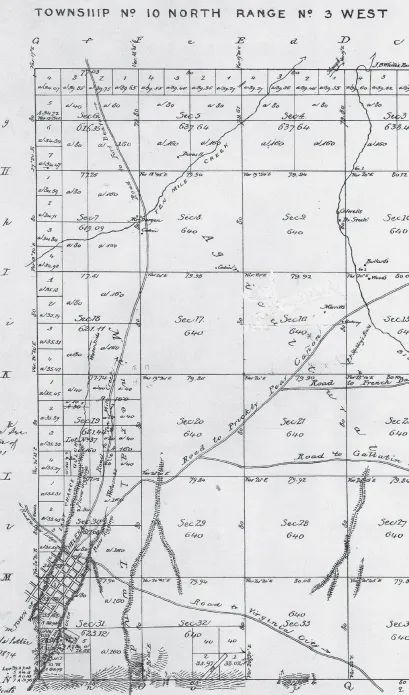

The 1868 Government Land Office map showing routes of both Benton Roads in the Helena Valley. From Montana Department of Natural Resources and Conservation.

Once the wagon trains reached Helena, they camped outside of town, either near the present location of the railroad depot or just off today’s I-15 Cedar Street Interchange. Last Chance Gulch was too narrow to accommodate many wagons and choked traffic to Bridge Street, Helena’s first commercial district. The freighters took turns driving their teams into the gulch and delivering supplies to the camp’s merchants. A feeling for this Helena tradition can still be experienced by anyone who tries to navigate the gulch during the morning delivery times for the many businesses that line the street.

Although Helena folklore reports that Benton Avenue is the old Benton Road, there is no strong evidence that supports that belief. While minor portions of it may have been, historic maps of Helena suggest otherwise. Portions of Benton Avenue were originally known as Senior Street until March 1887, when the city commission designated it as part of Benton. The 1884 Sanborn Fire Insurance map of Helena indicates that Benton Avenue terminated at the intersection of Holter Street and later extended north past Carroll College to the combination city golf course and airfield. The street, moreover, was named in honor of the late Thomas Hart Benton, a Missouri senator and famous proponent of westward expansion.

Contrary to popular belief, the rock retaining walls adjacent to South Park Avenue were also not part of Benton Road. In fact, little is known about the road or the retaining walls. They do not appear in an 1875 Helena street map of the city but are apparent in an 1885 photograph of the Reeder’s Alley area. The fire insurance maps show it as an “unimproved alley” but without the walls. It is not known who constructed them. The stone for the walls was likely quarried on Mount Helena by Jacob Adami and his sons. The old road, which is now closed to traffic, was certainly designed for wagon traffic, not for today’s automobiles, and may have been part of the road to Unionville and Park City. The origin of the prominent retaining walls is one of Helena’s enduring mysteries.

Sojourners today miss much of the adventure that travelers experienced on Benton Road in the late nineteenth century. No longer are they subject to broken axles, runaway horse teams, massive potholes, rickety bridges and price gouging by toll keepers. Indian attacks and the laboriously slow plodding of the ox teams are also a thing of the past. But motorists today still share the excitement and relief of rounding the Scratch Hills and seeing Helena spread out before them.

2

STOPPING ALONG THE WAY AT THE SIEBEN RANCH

By Ellen Baumler

The Sieben Ranch in the Prickly Pear Valley is a special heritage place that reveals a diversity of human experience, a depth of contribution and an important pattern of stewardship. But its story, intertwined with the larger Prickly Pear Valley, began in the dim past when the valley lay in the shadow of the Bear’s Tooth. This impressive landmark—two massive peaks resembling a bear’s open jaw—guided generations of Native American travelers on the Old North Trail from Canada to Mexico. The MacHaffie quarry site near Montana City preserves evidence of these early migrations where the first people stopped to make tools some twelve thousand years ago. More recent Native American art on local cliff faces is further evidence of those who passed before.

Members of the Lewis and Clark expedition explored the region, naming Prickly Pear Valley for the painful cactus that penetrated their moccasins. They also knew about the Bear’s Tooth from Nicholas King’s 1803 map of the Northwest, which shows the landmark just above what the expedition named “Gate of the Rocky Mountains.” Isaac Stevens passed through in 1853, scouting a route for the Northern Pacific, and John Mullan’s wagon road eventually passed through the valley.

Malcolm Clarke was among the valley’s first settlers. He left a tragic legacy. Twice expelled from West Point for fighting with fellow cadets, in 1841, Clarke signed on with the American Fur Company as a clerk at Fort McKenzie, above the later site of Fort Benton. Clarke’s two wives—Coth-co-co-na (Kohkokima), a Piegan woman, and Good Singing Sandoval, a mixed-race woman—made him an asset to the fur trade. But a fatal encounter with Owen McKenzie, son of Fort McKenzie’s founder, forced Clarke to move his family to the Sun River experimental agricultural station, where he was hired to reverse its financial misfortune. This Clarke accomplished, but when Indian agent Gad Upson arrived for inspection, the carousing Clarke had fostered earned him prompt dismissal.

The Bear’s Tooth, sketched in 1868, guided travelers until an earthquake destroyed one of its tusks in 1878. From A. E. Mathews, Pencil Sketches of Montana.

Clarke and his large family relocated to acreage in the Prickly Pear Valley in 1864, on the cusp of gold discoveries at Last Chance Gulch. The Clarkes offered primitive lodgings and fresh horses for the stage along the well-traveled Benton Road that skirted the Clarke ranch. Early Montanans esteemed Clarke for his thirty years in Montana. In February 1865, Clarke was among the twelve prominent Montanans who signed the act incorporating the Montana Historical Society. He had more longevity in Montana than any of them.

Acting territorial governor Thomas Francis Meagher and Judge Lyman Munson were Clarke’s guests in 1865. They enjoyed champagne and a fine meal. Clarke’s cultivated acreage, his prize horses and his accomplished daughter Helen greatly impressed Meagher. But saddles and blankets served as beds, and the men slept under a shed with their rifles loaded. While their picketed horses foraged around haystacks, sentinels patrolled the camp. Times were uncertain, and no one was entirely safe.

Malcolm Clarke was the first owner of the far-famed Sieben Ranch. From Helen Fitzgerald Sanders, A History of Montana.

Good Singing died during childbirth in 1868, and in 1869, a dispute over horses prompted Coth-co-co-na’s relatives to murder Clarke. He was buried in the nearby cemetery alongside Good Singing, their stillborn daughter Mary Ann and several of their other children. Retaliation for Clarke’s murder led to the tragic Baker Massacre a few months later.

Scotsman James Fergus and his wife, Pamelia, acquired the Clarke ranch and moved there in 1872. Fergus raised cattle; blooded horses; and marketed beef, grain, hay and potatoes. Pamelia ran the stage station, hotel and restaurant. She built a business, selling fifty to one hundred pounds of butter every week to restaurants, grocers and private customers. James Fergus was heavily involved in local politics, served on the Board of County Commissioners for most of the 1870s and was chairman from 1875 to 1877. Fergus also had a fine library.

After the Battle of the Big Hole in the fall of 1877, General William T. Sherman, commander-in-chief of the U.S. Army, traveled through Helena to visit recuperating survivors and stopped at the Fergus ranch. Upon inquiring about the small graveyard, he was shocked to discover that Malcolm Clarke, a fellow West Point classmate, was buried there. Sherman had regretted losing touch and always wondered what became of him.

The Ferguses weathered a personal crisis in 1876 when their youngest daughter, Lillie, got pregnant. Her suitor had left to buy land in Iowa. When he returned, Lillie was within weeks of delivery, and the time for a proper wedding had passed. The couple quietly said their vows, and James Fergus did not attend the ceremony. The newlyweds left immediately for their farm in Iowa. Despite Pamelia’s efforts to keep the pregnancy quiet, all the neighbors gossiped about it.

Indians had warned early settlers about frequent earthquakes. Tremors and several quakes were recorded during the nineteenth century, including one that claimed the Bear’s Tooth. In February 1878, a hunting party noticed a brief rumbling of the earth. When they reached the Bear’s Tooth, they discovered one of its tusks—a perpendicular mass of rock three hundred feet in circumference and five hundred feet tall—had dislodged and tumbled down the mountainside, leveling an entire forest. The loss of the tooth left only one peak, and the landmark became a hazy memory. Its replacement, the Sleeping Giant, was not recognized until 1893. The giant’s nose is the remaining tusk.

The Sieben Ranch lies in the shadow of the remaining tusk of the Bear’s Tooth, known since the 1890s as the Sleeping Giant. From author.

James Fergus intended to make substantial sums racing and breeding horses on his ranch. He paid an astounding $3,000 for two blooded stallions, Fayette Mambrino and Don A, hoping to realize substantial income from stud fees. Fayette Mambrino grew ill and died in 1878. It was an economic calamity for Fergus and many western Montana horse breeders who had counted on breeding their thoroughbred mares with t...

Table of contents

- Front Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Dedication

- Contents

- Introduction: More from the Quarries of Last Chance Gulch

- 1. Getting Here from There: Helena and the Benton Road

- 2. Stopping Along the Way at the Sieben Ranch

- 3. What’s in a Photograph?: Bridge Street, 1865

- 4. Life and Death on the Frenchwoman’s Road

- 5. Before There Was Deadwood

- 6. An Oasis of Questionable Virtue: Seven Mile House

- 7. Helena’s Public Heart

- 8. Red-Light Businesswomen

- 9. Trouble with Neighbors: The House of the Good Shepherd

- 10. Was Helena Invaded by Hairy Aliens in 1976?

- 11. The Hanging of the Golden Lanterns: Nighttime Airway Beacons Surround the Capital City

- 12. They Shall Not Pass: The Ground Observer Corps and the Helena Filter Center

- 13. Planting the Seeds of Saint Peter’s Hospital

- 14. Unraveling the Myths of Helena’s Chinatown

- 15. The Joe Louis of the Mat: The Saga of “King Kong” Clayton

- 16. To Ornament the City: Jewish Landmarks

- 17. Building a Better Helena: The Southside Lime Kilns

- 18. Haunting on Holter Street

- 19. The Great Canyon Ferry Flying Saucer Hoax

- 20. Bryant School’s Unusual Friends

- Bibliography

- About the Authors