- 288 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

'Charles Guthrie has been one of Britain's foremost soldiers as well as a terrific personality throughout his remarkable life. It is great that he is now telling his own story.' - Sir Max Hastings

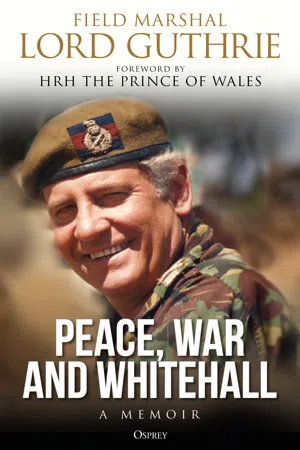

Field Marshal the Lord Guthrie commanded at every level in the British Army from platoon to army group, and was Britain's senior military commander at a time of great change. He oversaw the modernization of the armed forces following the Cold War years and led Britain's military involvement in operations in the Balkans and Sierra Leone.

Charles Guthrie was commissioned into the British Army in 1959 at a time when Britain's influence was shrinking throughout the world, and Peace, War and Whitehall describes his operational experience with both the Welsh Guards and 22 SAS in Aden, Malaya, East Africa, Cyprus and Northern Ireland.

As a senior officer he commanded the Welsh Guards during an operational tour of the Bandit Country of South Armagh at the height of the Troubles, before leading an armoured brigade in Germany in the midst of the Cold War, and eventually being appointed Commander-in-Chief of the British Army of the Rhine and Northern Army Group as the Cold War ended and the former Yugoslavia began to disintegrate into savage internecine warfare.

Peace, War and Whitehall details Lord Guthrie's extraordinary career from a young platoon commander through to Chief of the Defence Staff.

Field Marshal the Lord Guthrie commanded at every level in the British Army from platoon to army group, and was Britain's senior military commander at a time of great change. He oversaw the modernization of the armed forces following the Cold War years and led Britain's military involvement in operations in the Balkans and Sierra Leone.

Charles Guthrie was commissioned into the British Army in 1959 at a time when Britain's influence was shrinking throughout the world, and Peace, War and Whitehall describes his operational experience with both the Welsh Guards and 22 SAS in Aden, Malaya, East Africa, Cyprus and Northern Ireland.

As a senior officer he commanded the Welsh Guards during an operational tour of the Bandit Country of South Armagh at the height of the Troubles, before leading an armoured brigade in Germany in the midst of the Cold War, and eventually being appointed Commander-in-Chief of the British Army of the Rhine and Northern Army Group as the Cold War ended and the former Yugoslavia began to disintegrate into savage internecine warfare.

Peace, War and Whitehall details Lord Guthrie's extraordinary career from a young platoon commander through to Chief of the Defence Staff.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Peace, War and Whitehall by Charles Guthrie in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & Military Biographies. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

Harrow

Harrow 1953–1957, more than just the sum of its days.

Fate, as I have often found, is a matter of choice, not chance. It was only towards the end of my time at Harrow in 1957 that I found myself having to take the first real choice of my life. To humour myself during my skirmishes with academic classwork, I had become an avid reader of C.S. Forester’s Hornblower books, the fictional adventures of a Royal Naval officer in the Napoleonic Wars. Contemporary films like In Which We Serve starring Noel Coward, and Anthony Quayle in The Battle of the River Plate further sparked my enthusiasm for a career in the navy. Like Anthony Quayle playing Commodore Harwood, I saw myself on the bridge of HMS Ajax giving orders to engage the German cruiser Admiral Graf Spee and keeping true to Nelson’s dictum before the battle of Trafalgar, “No Captain can do very wrong if he places his ship alongside that of the enemy.” I sought the spirit of adventure, travel, sport and the friendship of like-minded people.

In those days, there was no such thing as a careers master, let alone careers advice. Harrow’s masters might give you a steer but that was about it. Many boys would join the professions of their fathers or, if they were from the landed gentry, had little ambition beyond a leisured life running their estates. My father was a successful businessman, but I had no inclination to be something in the City. I had expressed my interest in a naval career to Major Jim Morgan, known as ‘Monkey’ Morgan. ‘Monkey’ reputedly had only one testicle, though how anyone knew that I never found out. Monkey taught me mathematics, and he also ran the School Combined Cadet Force (CCF).

The Harrow CCF, as in most traditional public schools, sought to encourage its pupils to join one of the services. Many of my friends had lost their fathers in the Second World War. It was understandable that they should seek the spirit of their lost fathers in a service career. Monkey arranged for me to go and visit the navy in Portsmouth. A university friend of his was now Captain of HMS Dainty, a Daring-class destroyer.

HMS Dainty didn’t strike me as a promising name for a destroyer, and my visit quickly dispelled any idea I might have had of standing on a ship’s bridge, enveloped in a duffel coat, peering through a pair of Barr and Stroud naval binoculars and sinking the enemy. The Captain, whose name I cannot remember, was a sparse figure with a shock of marmalade-coloured hair.

Monkey Morgan had told me that the Captain had been on the Arctic convoys during the war. The Captain’s laconic manner, and his eyes that appeared fixed on some far point on the horizon, suggested difficult and trying times in his past. After he had asked me a little about myself and if I had any family members who had served in the navy, he remarked that we should now go and see where the action took place.

The action, if you could describe it as such, took place below the waterline. As we made our way down into the bowels of the ship, I noted the grey but largely cheerful faces of the ship’s crew. Two huge boilers and two steam turbines dominated the engine room. I dimly remember the Captain firing statistics at me: “Displacement 4,000 tons, new Squid anti-submarine mortars, 34 knots, enough fuel oil to take us to Malta and back…”

I was at a loss for words and mumbled, “How do you command the ship when engaging the enemy?”

“Well, that’s the easy part,” he said. “More or less down to pressing a few buttons and radar fire control, Bofors 40mm cannon and 21-inch torpedoes. I sit down here and let the gunnery and weapons officers get on with it. Not too troublesome, really.”

I took the train back to London knowing that the navy was not for me. I wanted excitement, my reach to exceed my grasp, and though many years later as CDS I was full of admiration and respect for Britain’s Senior Service, I realised then my temperament was not really suited to it.

In the evening of my memory, I often return to Harrow. I had been to a prep school which had close links to Winchester College. My father was a Wykehamist and naturally was keen that I should follow him there. My prep school Headmaster with admirable foresight persuaded my father that Harrow would better suit my talents, adding that he did not see me in later years in the higher reaches of the judiciary or tax planning. That was a little unfair to Winchester, which has produced many fine soldiers.

Harrow School’s ethos was then, as it still is today, “To prepare boys for a life of leadership, service and personal fulfilment”. As I penned these memoirs, I thought about those principles and how they had formed my life after Harrow.

Until the age of 15, I was no different from most boys: argumentative, unkempt, the usual maddening teenager. Beating and ‘fagging’ (the running of errands for senior boys) was still going on at Harrow in the ’50s. Both practices died out soon after.

My contemporary and close friend to this day, Dale Vargas, who went on to teach and become a housemaster at Harrow, and who wrote The Timeline History of Harrow School, said that fagging developed at the great public schools to teach boys how to treat their servants fairly at home. As we never had servants, the arcane practice was lost on me.

On the cusp of 16, I was, however, beaten for some trifling misdemeanour by the head of house, who was 18. He didn’t amount to much as a leader or head of house, and I think he just wanted to establish his authority over me. It is an odd thing to say that I was indebted to this individual. Not because he forced me to wake my ideas up, but because it awoke in me a belief that I was to carry throughout my career: that the inappropriate use of authority is a false step.

Like many boys, I drew great personal fulfilment through sport, particularly rugby football. It has remained with me throughout my life. With the arrival in 1950 of A.L. Warr, an Oxford blue and England International, Harrow Rugby enjoyed a remarkable revival, unbeaten in 1954. We lost just one match in 1955 and 1956 when I captained the team, playing alongside Robin Butler, who was later to become Head of the Home Civil Service under Prime Ministers Thatcher, Major and Blair. Playing competitive sport taught me all the usual attributes of teamwork, communication, resilience and losing with grace. It also gave me the priceless gift of friendship and a much better understanding of how to instil confidence in others.

Everyone needs a hinterland, a backdrop to their lives apart from the love of family and friends, which gives them somewhere to travel to in life’s uncertain moments. My love of drama and music started at Harrow, where the tradition of the annual Shakespeare play in the Speech Room started as a result of a German bomber dumping its bombs on the school in 1940. The Speech Room’s roof was blown off, giving Harrow’s legendary Head of Drama, Ronnie Watkins, an opportunity to replicate the Elizabethan open-air Globe Theatre.

My first foray as an actor was as Peaseblossom in A Midsummer Night’s Dream. I was dressed rather suggestively, attracting whistles from the boys and a kiss on the lips from Blossom, played by James Fox, whose acting talent marked him out for the later stardom he went on to achieve.

My fondness for opera, which came later in life, was inspired by Harrow’s preference for large-scale choral works. After morning Chapel, the whole school would trudge across to the Speech Room to rehearse in our choral unison role. Many years later, while commanding my Regiment on a particularly demanding operational tour in South Armagh, I was listening one evening in my room to ‘The Chorus of the Hebrew Slaves’ from Verdi’s opera Nabucco, quite oblivious to the fact that we were under mortar fire from the IRA. Amusingly, and to my unintentional credit, word went round the Regiment that the commanding officer was a pretty cool hand if he could listen to opera while under mortar fire. ‘The Chorus of the Hebrew Slaves’ was to become my first choice of record when I was invited by Sue Lawley as a guest on Desert Island Discs in 2000, when I was CDS.

Harrow may not have been particularly enlightened in its outlook in the 1950s, but it did allow boys a considerable amount of freedom and responsibility in how the school’s daily business was run. The masters were there to teach, and the housemasters there to ensure their individual trains kept on the tracks. But they rarely interfered.

The Headmaster in my time was Dr James, a double first in classics, and known as ‘Jankers’. He was politically astute, a fine delegator, and seemed to know exactly what was going on without apparently leaving his study. His study reflected his temperament: neat, low-key and conservative. He had the gift of appearing to have time for everyone.

Before my final year, Dr James called me in to his study and asked if I would like to be Head of School. We had struck up a rapport because he seemed to think that, as captain of rugby, I knew what was going on in the school. He would often call me in to his study for a chat to hear, as he described it, “the news from the bazaar”. I enjoyed these chats as it allowed me to miss lessons.

I remember on one occasion the worthy but uninspiring school chaplain knocked on the door, peering round to say, “Headmaster, may I have a word about next Sunday’s sermon?”

Jankers replied, “Not now, Chaplain. By all means pop in later, but I’m talking to Guthrie about something much more important.”

Ironically, it was more important. The Headmaster said he would like me to organise the Queen’s visit the following term – the Lent term of 1957. It was the first time the Queen had visited the school, and she was the first monarch to do so since King George V. Like any good delegator, the Headmaster set clear expectations with advice that the Press should be kept at arm’s length, that no boy should be seen snivelling in the corridors, and that time spent in rehearsal would ensure success.

The Headmaster had a pathological distrust of journalists, particularly those from the Mail and Express whose sole purpose, he thought, was to unearth any scandal they could. Given the visit’s importance – Prince Philip was to accompany the Queen – I knew we had to work in partnership with the Press, an experience which served me well throughout my army career.

The visit was considered sufficiently newsworthy to be filmed by Pathé News, the popular producer of film and newsreels at the time. Bob Danvers-Walker, the unmistakable ‘Empire’ voice of Pathé News, gave a characteristically upbeat commentary to the day’s events, though he was a little lost in his commentary when I arranged for the Queen and Prince Philip to watch the boys milking cows in the school farm.

I overheard Prince Philip remarking to one boy, “Used to this at home, are you?” to which the boy replied, “Not exactly, Sir, we live in Belgravia.”

The day finished in the Speech Room with the boys singing ‘Forty Years On’, one of the great traditional Harrow Songs. At the end I called for “Three Cheers for Her Majesty!” The response was resounding.

It was a demanding task for a 17-year-old boy to organise such a visit, but I was thankful for the ordeal, as exactly 20 years later it was left to me to organise much of the ceremonial for the Queen’s Silver Jubilee celebrations while serving as the Brigade Major (Chief of Staff) for The Household Division. The Queen reminded me at the time of the Silver Jubilee that she had met me before and recalled her visit to Harrow with affection. She had, she said, been intrigued to see what life was like in a boys’ boarding school.

Not all aspects of Harrow life were deemed opportune. Flogging and fagging, the former ceasing in the 1970s and the latter phased out in the 1980s, were not part of Her Majesty’s visit programme.

For role models on leadership and courage, Harrow was blessed. We had produced seven prime ministers, including Peel, Palmerston, Baldwin and Churchill, and the first Prime Minister of India, Jawaharlal Nehru. Fifty-five Harrovians fought at Waterloo under Wellington, Britain’s greatest military commander, who has always been a hero of mine.

Banners of the 19 Old Harrovian winners of the Victoria Cross hung in the Harrow War Memorial building. Just under half of the 2,917 Harrovians who served in the Great War were killed or wounded.

Field Marshal Alexander of Tunis, an Old Harrovian, was an inspiration. His son, Brian, was a contemporary of mine. Leadership and courage were in the fabric of the institution and I could not help but absorb its weave.

Like most school corps at the time, the Harrow Rifle Corps was unimaginative and unenlightened, with a dreary emphasis on drill, cleaning belts, polishing shoes and the parade ground.

It is a rule of thumb of mine that boys who flourish in their school corps are a menace if they go on to pursue a career in the services. The head of house who had beaten me when I was 16 encouraged me to join the corps, saying, “No boy will be the worse in the after-life for being able to change step and slow march properly.”

That might be true enough, but I have always felt that school sport, at whatever level, was a much better preparation for leadership, team-working and instilling confidence.

There is a rather touching scene in the film Young Winston when the Headmaster of Harrow, the Revd James Welldon (played by Jack Hawkins) accepts Churchill ...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half-Title

- Dedication

- Title

- Contents

- Foreword: HRH The Prince of Wales

- Preface: Major General Richard Stanford, CB, MBE, Regimental Lieutenant Colonel, Welsh Guards

- List of Illustrations

- Prologue

- 1 Harrow

- 2 The Welsh Guards

- 3 Aden

- 4 The SAS

- 5 Germany

- 6 Belfast

- 7 Military Assistant to the Chief of the General Staff

- 8 Cyprus

- 9 Brigade Major, The Household Division

- 10 Commanding the Welsh Guards in Berlin

- 11 Commanding the Welsh Guards in South Armagh

- 12 The Coconut War

- 13 Commander, 4th Armoured Brigade

- 14 Sport

- 15 Reflections on Command

- 16 Kate

- 17 Commander-in-Chief, British Army of the Rhine

- 18 Chief of the General Staff

- 19 Gold Stick, Colonel of The Life Guards

- 20 Chief of the Defence Staff

- 21 The Hinterland

- Epilogue

- Acknowledgements

- Plates

- Copyright