- 160 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Lost Miami Beach

About this book

"America's Playground" has seen many changes over the years. From architectural to botanical, Lost Miami Beach covers these changes and the development of the current preservation strategy.

Miami Beach has been "America's Playground" for a century. Still one of the world's most popular resorts, its 1930s Art Deco architecture placed this picturesque city on the National Register of Historic Places. Yet a whole generation of earlier buildings was erased from the landscape and mostly forgotten: the house of refuge for shipwrecked sailors, the oceanfront mansions of Millionaires' Row, entrepreneur Carl Fisher's five grand hotels, the Community Theatre, the Miami Beach Garden and more. Join historian Carolyn Klepser as she rediscovers through words and pictures the lost treasures of Miami Beach and recounts the changes that sparked a renowned preservation movement.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

CHAPTER 1

BISCAYNE HOUSE OF REFUGE

Florida was the nation’s last frontier, and it had much in common with the American West.

Both waged wars on their native populations. In Florida, the First Seminole War (1817–18) occurred under Spanish rule due to problems with border security. In 1821, Spain agreed to sell its Florida territory to the United States; then the Second Seminole War (1835–42) arose from Seminole resistance to forced relocation to the Arkansas and Oklahoma territories. Florida achieved statehood in 1845, the same year as Texas and five years before California.

In 1862, the U.S. government passed the Homestead Act for the purpose of settling federal lands in both Florida and the western territories. The act granted 160 acres of public land free to any adult citizen who improved it and lived on it for five years. Alternatively, one could purchase it for $1.25 per acre after only two years, but even this was a forbidding prospect in the steamy tropical wilderness of southern Florida

In 1860, the West had the Pony Express; in the 1880s, southern Florida had the Barefoot Mailman, who made a weekly round trip from Palm Beach to the Miami River (there was no Miami until 1896), a total of eighty miles on foot and fifty-six by rowboat or sail.

Both Florida and the West were opened up by the railroads. America’s first transcontinental rail line traversed the West in 1869. In 1886, Standard Oil partner Henry Flagler began consolidating and constructing rail service down Florida’s Atlantic coast, starting at Saint Augustine. What was eventually known as the Florida East Coast Railway reached Palm Beach in 1894 and the Miami River in 1896. By 1913, another 150 miles of track had been built through the Florida Keys to Key West, a thriving city for fifty years despite being accessible only by boat.

One problem in Florida that one didn’t find so much out West was shipwrecks. The problem was not that ships would crash on rocks but rather that they would grind to a halt on the submerged reefs and constantly shifting sandbars and capsize, especially during storms. (We are talking about sailing ships here.) The crew and passengers could make it to shore, but on that desolate coast, they would soon perish of thirst and exposure. One such incident in October 1873 made national news when the crew from a wreck just north of present-day Miami Beach survived only because a beachcomber came across them.1 Consequently, President Ulysses S. Grant ordered the United States Life-Saving Service (which became the Coast Guard in 1915) to construct a series of houses of refuge along the Florida coast. The first five were built in the winter of 1875–76; from north to south, they were called Bethel Creek (thirteen miles north of Fort Pierce), Gilbert’s Bar (near Stuart), Orange Grove (Delray Beach), Fort Lauderdale and Biscayne (near present-day Seventy-second Street in Miami Beach).

By 1885, six more houses of refuge had been built in Florida, as well as two lifesaving stations (at Pensacola and Jupiter), whose mission was to go to the rescue of ships in distress. The houses of refuge were meant only to provide food, fresh water, clothing and lodging to stranded mariners and return them to civilization. The houses were two-story frame structures and were spaced approximately twenty-six miles from one another or from a lighthouse so a castaway would not have to travel more than thirteen miles one way or the other. Signs were posted along the beach to point the way to the nearest aid. Each house of refuge held enough provisions for twenty-five people for ten days. For safekeeping of the supplies, and to watch for wrecks and keep the signs in good repair, a keeper and sometimes his family lived in each refuge.2

All eleven of the Florida houses of refuge were built to the same plans, drawn by Francis Ward Chandler, architect for the Life-Saving Service, who was from Boston and a graduate of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. In addition to the Florida structures, he designed lifesaving stations on the Pacific and Great Lakes coasts. The house of refuge buildings were of pine with cedar shingle roofs and were fifteen feet wide by thirty-seven feet long, plus an eight-foot-wide veranda that wrapped around three sides.3 Each site also had an observation tower, a privy, sheds and a boathouse for the keeper’s use.

The Biscayne House of Refuge as a U.S. Coast Guard Station in 1925, with the “beach road” in the foreground. Courtesy Miami-Dade Public Library, Gleason Romer archive 7B.

Hannibal D. Pierce, who had left Chicago during its Great Fire, was the first keeper of the Orange Grove House of Refuge at Delray Beach. His son Charles describes the house in his memoir, Pioneer Life in Southeast Florida:

The houses of refuge were built to withstand storms and hurricanes. The foundation was framework of 8 by 8 timber placed some three or four feet in the ground: onto this framework were mortised 8 by 8 posts that in turn were mortised into the sills and held there by large wooden pins. The roof extended over the porches on each side of the building…The porch at the north end was enclosed for a kitchen and supplied with a fireplace and brick chimney. This chimney proved a source of much trouble later on: it smoked badly when there was a strong wind from the northwest or north as the chimney was too short for a proper draft.

All of these houses were built exactly alike, and all of the keepers used the four rooms on the ground floor in the same order as we did. The south room was a bedroom and the next was always used as a living room; the next was a dining room and then the kitchen. North of the kitchen was the cistern, built in the ground and made of brick. Eave troughs led from the house to this cistern, which was the only water supply furnished by the government. The shingles were new unseasoned cypress and when we arrived the cistern was full of water from this new roof. It was brown in color, bitter, and with a strong cypress flavor, more like medicine than drinking water.

The house…had a second story dormitory for shipwrecked sailors.4

A few years later, in 1883, Hannibal Pierce was appointed keeper of the Biscayne house. Charles worked as his assistant and describes the keeper’s duties:

There was not much to do except keep a lookout for anything that might appear in sight on the ocean or on the beach. We had to keep the log and enter in it the number of brigs, barks, ships, and steamers that passed each day. We also entered the state of the weather and sea and the direction of the wind. We made barometer and thermometer readings three times a day. The service asked that these records be kept, yet it did not furnish any of the instruments. We happened to have a good barometer that belonged to my uncle and a thermometer of our own, so we kept proper records.5

A highlight of Pierce’s term at Biscayne was when the coconut planters came through. In 1882, New Jersey entrepreneurs Elnathan Field, Ezra Osborn and Henry Lum had purchased about sixty miles of oceanfront land extending from Key Biscayne to Jupiter, Florida, and planned to start a coconut plantation. Coconuts were valued for coir, the husk fiber used to make rope, and copra, which produces oil. Very few coconut palms were growing naturally in this area at that time. Over three years, this group hired a schooner to bring more than 330,000 coconuts from Trinidad, Nicaragua and Cuba and had a team of off-season Atlantic City lifeguards plant them along this trackless coast. Because there was no customs officer in the area, the Key West customhouse appointed Hannibal Pierce to supervise the offloading of the coconuts in 1883. Charles helped with the planting and recounts it in his memoir. The coconut plantation failed, but this was an important episode in Miami Beach history because one of the New Jersey investors in the project was city founder John S. Collins.

John Thomas (Jolly Jack) Peacock, an Englishman who settled in Coconut Grove, succeeded Hannibal Pierce as keeper of the Biscayne house from February 1885 to July 1890. His son Richard Peacock was born there on November 4, 1886, the first recorded birth in what would become Miami Beach. William H. Fulford, a former ship’s captain, was the next keeper at Biscayne, from July 1890 to April 1902. The Miami Metropolis reported that he killed a nine-foot crocodile behind the house of refuge in 1896, with two rounds from a shotgun:

The coconut planters in the 1880s would dismantle these shacks and reassemble them as they progressed along the coastline. Courtesy Arva Moore Parks, Ralph Munroe collection.

For some time the beast had been permitted the freedom of the grounds as a sort of pet, but on the day he was killed he was in a savage mood and was lashing the water furiously a short distance away from where Capt. and Mrs. Fulford were making a landing.6

During his service, Fulford acquired one of those 160-acre tracts under the Homestead Act in the area of present-day 163rd Street; it later became the town of Fulford. After he left the house of refuge, Captain Fulford was his town’s first postmaster. The town of Fulford was renamed North Miami Beach in 1931.

The last keeper of the Biscayne house was Laurence F. (Frank) Tuten, who took over in 1917. By that time, Miami Beach was already a city a few miles to the south, and the house of refuge had outlived its original purpose. The Coast Guard officially discontinued it after World War I, but Tuten stayed on there with his family until the September 1926 hurricane, keeping a lookout for rumrunners during Prohibition. He needed only to turn his spyglass landward; by the early 1920s, a two-story log house known as the Jungle Inn stood just a few hundred yards away, at what is now the southeast corner of Abbott Avenue and Sixty-ninth Street. Outside the city limits and surrounded by empty land, it was a notorious speakeasy and had a gambling parlor upstairs. An exposé in the Miami Metropolis led to a raid in 1923.7

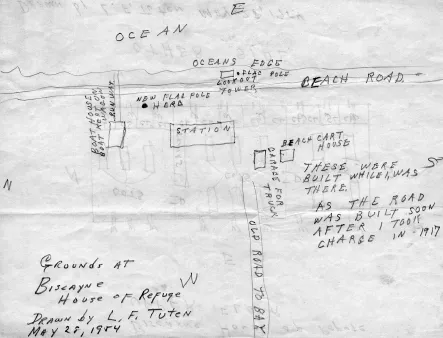

The sketch of the Biscayne House of Refuge site that its last keeper, Frank Tuten, drew from memory. Courtesy HistoryMiami.

Tuten’s wife, Helen, died in 1925. During the hurricane the following year, Tuten and his young son narrowly escaped as the house of refuge blew off its foundations.8

In 1954, when he was interviewed for an article in the Miami Herald, Frank Tuten made a pencil sketch of the Biscayne House of Refuge site that is now in the HistoryMiami archive. What is interesting about this sketch is that it shows a “beach road,” with Tuten’s notation that “the road was built soon after I took charge in 1917.” There will be more about this road in Chapter 5. It was built by the Tatum brothers.

Bethel B., Johnson R. and Smiley M. Tatum were Georgia boys. Bethel moved to Florida in 1881 at age seventeen and worked in the newspaper business. Johnson Tatum, two years younger, went to business college and moved to Miami in 1911, working in banking and insurance. The third brother, Smiley, was a chemist for many years in Bartow, Florida, until acid fumes injured his eyes. He moved to Miami in 1902.9

In Miami, the brothers formed a number of realty and investment firms, platted several subdivisions there and, in Florida City, developed vast tracts of the Everglades. The Tatums Ocean Park Company owned most of the oceanfront land north of the Biscayne House of Refuge, extending up to Fulford (163rd Street), but it was difficult to access. On September 11, 1917, the Tatums and other property owners gained from the Dade County Commission the right of way to build a coastal road from the Miami Beach city limits, which were then near present-day 46th Street, up to the beach adjacent to Fulford, a stretch of about seven miles, in order to access their land. After the road went through, the Tatums began, in 1919, to plat their six Altos del Mar subdivisions, followed by Ocean Beach Heights in what is now Bal Harbour and Tatums Ocean Beach Park in what is now Sunny Isles.

In 1922, at the Tatums’ request, a land survey was conducted in the vicinity of the house of refuge because they felt they were being taxed for more land than they owned. The tax outcome is unknown, but the survey revealed that the Biscayne House of Refuge had been constructed about two hundred feet south of its tract of U.S. government land. The Treasury Department took bids for moving it; accepted one on February 12, 1923;10 and shortly thereafter, the house and its outbuildings were hauled no farther than necessary to the south end of the government property. It is really not surprising that the house had been built out of place since there were no landmarks at that time and surveying was rather hit or miss.

(The Fort Lauderdale House of Refuge had also been built off its intended site because the lumber for its construction had been floated ashore, and the ocean currents carried it a mile and a half to the north. The house was built where the lumber landed, which was easier than carrying it back. In 1891, while undergoing repairs, that house, too, was moved to its proper location.)11

After fifty years, the Biscayne House of Refuge had become obsolete, and it was torn down after the 1926 hurricane damaged it beyond repair. The local Coast Guard station placed a new bronze plaque at its site at Seventy-second Street in 2004. The only house of refuge still standing is the one at Gilbert’s Bar near Stuart, Florida, which is now a museum.

CHAPTER 2

OCEAN BEACH

Many people built Miami Beach. At the beginning, Elnathan Field, Ezra Osborn and Henry Lum bought the land for their coconut plantation in the 1880s. Henry Lum died in 1895, and his portion of land went to his son Charles.

In 1901, four years before the Government Cut shipping channel opened, Richard M. Smith built a two-story wooden pavilion on Lum’s land, on the beach just north of where the cut would be. It had a hig...

Table of contents

- Front Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Contents

- Acknowledgements

- Introduction

- 1. Biscayne House of Refuge

- 2. Ocean Beach

- 3. The Miami Beach Improvement Company

- 4. Fifth Street

- 5. Ocean Drive

- 6. Millionaires’ Row

- 7. Other Homes

- 8. Lincoln Road

- 9. The Carl Fisher Hotels

- 10. Other Hotels

- Notes

- Selected Bibliography

- About the Author

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Lost Miami Beach by Carolyn Klepser in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & North American History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.