![]()

Chapter 1

THE ABENAKIS AND SOKOKIS

The early settlers of New England and New France had little in common other than the urge to immigrate. The English were Protestants. The French were Roman Catholics. Their mother tongues were quite different, and it was not surprising that the English and French had altogether different names for identical Indian tribes.

The tribal name of Abenaki was derived from Wobanaki (“Land of the East”), the name given by the Canadian Algonguins to the country of the Canibals and other Indians of Acadia. The French called these Indians the Abenaquiois and later Abenakis, which means the “Indians from where the daylight comes” or the “people of the East.” This name was first applied to all Native Americans from Maine to Nova Scotia, but later, it was given in particular to those living in Maine from the Saco River to the Penobscot.

The tribal name of Sokoki was derived from Sokoakiak, “a person from the south” or “one living under the noon-day sun.” It applied to those living between the Saco and Connecticut Rivers, which included most of what is now New Hampshire. The French called them Sokoquiois and later Sokokis.

Their campsites and villages were scattered throughout the state and were known to English merchants and fur traders by Indian names that described the localities in which they lived. For instance, the Coosucks lived at the Pine Place, the Pennacooks at the Crooked Place, the Suncooks at the Rocky Place, the Naticooks at the Cleared Place and so on. As neighbors, the English were much better acquainted with the New Hampshire tribes than the French, who lived two or three hundred miles away.

Under the peaceful leadership of Passaconaway and Wonalancet, the Sokokis did not become involved in either the Pequot War or King Philip’s War, which we shall examine later in the chapter on Indian warfare.

During the European colonization of New England, the land occupied by the Abenakis was in the area between the new colonies of England in Massachusetts and those of the French in Quebec. Since no party agreed to territorial boundaries, there were regular conflicts between them. The Abenakis were traditionally allied with the French. During the reign of Louis XIV, Chief S’Assumbuit was designated a member of the French nobility for his service.

Independent of the Abenakis, the chiefs did not take part in the Indian wars of Maine, which ranged from 1676 to 1679. Those who followed their Jesuit missionaries to Canada and founded the village of St. Francis did so from their own choice and not because they were forced out by the English.

The Pestilence of 1616–1618, which resembled yellow fever, was fatal to about 90 percent of the New Hampshire tribes and affected the Maine Indians to the same degree. Up until this time, the Sokokis and Abenakis had more than enough warriors to discourage the Mohawk raids into New Hampshire and the neighboring state of Maine. In 1633, an epidemic of smallpox swept through Maine, New Hampshire and eastern Massachusetts, further weakening the tribes to such an extent that the Mohawks began raiding their villages with little opposition. Because of the infectious diseases, the Abenakis started to migrate to Quebec around 1669. The first was the St. Francis River, which is presently known as the Odanak Indian Village Reservation.

Jesuit missionaries spent considerable time with the Sokokis of New Hampshire between 1650 and 1660; their journeys were largely unsuccessful, especially in the southern part of the state. Diseases and wars provided a continuation of misfortunes for the Abenakis of Maine, but the Sokokis of New Hampshire had another misfortune still worse than those of the Abenakis: they were not acquainted Christianity. The Protestant ministers John Eliot and Thomas Mayhew lived among the Indians and conducted schools for many years. Eliot was always thought of as an apostle to the Indians. He spent much of his time traveling among the tribal villages, reading to them from the Bible, which he had translated into their language.

The New Hampshire Indians suffered more than the Abenakis from Mohawks because they were much nearer to their enemies. Mohawk raids continued to increase until it was no longer safe for the Jesuits to travel from tribe to tribe or carry on the missions. By 1660, the Jesuits had recalled many of their missionaries back to Canada. It was during the 1660s that several Sokoki families left New Hampshire and founded the village of St. Francis. Some of these people had never been converted by the Jesuit missionaries, but others were nearly ready to receive the sacrament of baptism. At St. Francis, they could bring up their children in the Catholic faith as missions had been established in several nearby communities. There was a mission de loups (wolves) at the Cowass meadows in Haverhill, New Hampshire. They thought they would be able to hunt and fish in Canada without fear of ambush, but it was only a few years until the Mohawks and other Iroquois tribes began sending large war parties into Canada to kill, loot and take prisoners.

By the 1670s, the Sokokis were well established in St. Francis. In September 1677, a party of Sokokis from St. Francis, some of whom were relatives of Wonalancet, visited Chelmsford and asked him to return with them to St. Francis. They told him “that the war in Maine might continue for some time and he would live better and safer with his friends in Canada.” His oldest son and his wife’s relatives already lived at St. Francis, so he decided to go and live there with them. Three of the men and their families went with him and stayed at St. Francis until the war with the eastern tribes was over. According to records in the New Hampshire secretary’s file in Concord, New Hampshire, Wonalancet was back at Penacook in September 1785 but was no longer the chief of his tribe

This was further reason to believe that the Sokokis were firmly established at St. Francis during the 1670s. At an assembly of the leading citizens of the district in October 1678 to get the opinion on the liquor trade with the Indians, Jean Crevier, whose trading post was located at the village of St. Francis, gave his opinion as follows:

If the trade in liquor was not permitted it would do considerable harm to the country, in that the large number of Sokokis who live here, and who acquired the drinking habit from the English, would go back there and deprive the Canadians of the large profit brought in by the trade, not knowing of any disorder from their drunkenness, and if it should happen it would not be because of that since the Ottawas who do not use liquor and are taught by the Jesuit missionaries, commit all sorts of crimes every day, which shows that it is their barbaric disposition which brings them to this wickedness and not the use of liquor.

The Sokokis who acquired the drinking habit from the English were no doubt from the Pennacook tribe as they lived nearer the settlements than the Coosucks or Pequakets.

Jean Crevier’s mention of the large number of Sokokis with whom he traded fur would indicate that they were well established at St. Francis in 1678. They had no parish register until 1687. Previous to that time, their records were kept at Sorel or Three Rivers. Sokoki children were baptized at Sorel as early as April 14, 1676. The first Abenaki infant mentioned was baptized on August 17, 1690.

The Abenakis formed an attachment to the French and their culture, mainly through the influence of their missionaries, and continued a constant war with the English during the turn of the century. The accounts of these struggles may be found in chapter three. As the early white settlers encroached on them, the Abenakis gradually withdrew to Quebec, Canada, and Vermont to protect the trade on Lake Champlain.

The Abenakis continued to migrate from Maine to Canada during the long wars that cost them their homes and land. The French welcomed them in Canada and provided village sites for them at Chaudière Rapids and Becancour. Some of them joined the Sokokis at St. Francis, Quebec, and with them carried out countless raids on the frontier settlements of New England. Outnumbered, the colony of New France would have fallen long before it did had it not been for their faithful Indian allies.

When the mission at the Chaudière Rapids was transferred to St. Francis during the 1700s, it caused the Sokokis to be greatly outnumbered by the Abenakis. In spite of this, the two tribes continued to hold their own identity. Each had its coat of arms and clan totem, the bear for the Abenakis and the turtle for the Sokokis.

Let us embellish on the clan totems and the tribal symbolism. The bear was called Ogawinno, or “the sleeper,” because he passed the whole winter in hibernation. The turtle was called Pelawinno, “slow moving,” because he took his time and enjoyed himself. These totems were often painted over the doors of the wigwams and tattooed on the tribe members’ bodies. The Abenakis chose the bear for their insignia because they greatly admired that animal. They never tried to get a second shot at a bear because they believed it would cost them their lives.

No one really knows why the Sokokis had such respect for the turtle, but it was likely because of its slow movements. Nearly all Sokokis kept little turtles made of stone with their other possessions, and these are sometimes found today beneath the surface of their primitive campsites.

For many years, the Indians of St. Francis were divided into two parties named after the animals on their totems. In their councils, the tribal names were never mentioned. Their speakers instead said, “Oganwinno thinks in this manner” or “Pelawinno thinks in that manner.” In playing such games as lacrosse, one team was called Ogawinnos and the other Pelawinnos.

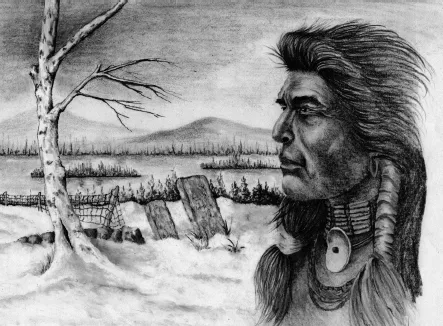

Abenaki Indian warrior overlooking Lake Winnipesaukee with Ossipee Mountain in the distance. Courtesy of author.

In addition to the Sokokis of New Hampshire, the Nipmucs, Pacomtucks, Mohegans and Missiassiks were all represented at St. Francis to some extent and all spoke similar Algonguian dialects. The Abenakis accounted for over 75 percent of the population, and it was only a matter of time before the smaller groups became absorbed by the larger one. Today, the people and their language are known as Abenaki, and we seldom hear Sokokis mentioned except by students of Indian history or at Missisquoi in Vermont.

In 1960, the people of the St. Francis Reserve at Odanak celebrated the 300th anniversary of the founding of their village by the Sokokis of New Hampshire. Hundreds of their friends came from miles around to enjoy singing, dancing, feasting and participating in their religious services. This was considered a day of remembrance.

CULTURE AND CUSTOMS

It was mentioned earlier that the Abenakis were a tribe of the Algonquian-speaking people of northeastern North America. They lived in the New England region of the country and in Quebec and the Maritimes of Canada. The Abenakis are one of the five members of the Wabanaki Confederacy. The confederation of Algonquian-speaking peoples inhabited New Hampshire before European settlement. By far the largest were the Pennacooks, located in the Merrimack River Valley near the present site of the capital city of Concord. These people of the Pennacook tribe lived in a fertile land, surrounded by cultivated fields.

Other groups of the Algonquian culture included the Sokokis north of the White Mountains, known as the Pigwackets, whose territory extended into western Maine in the upper Saco Valley in the Conways on the southeastern boarder of the White Mountains, and the Pocumtucks of western Massachusetts, whose territory extended into the lower Connecticut Valley of New Hampshire

Indian scholar Solon Colby states the following:

The Abenakis lived in bands of extended families and were considered extremely friendly. Hospitality was to them an unwritten law that would be obeyed and was part of their nature. Each man had different hunting territory inherited through his father, During the spring and summer months, bands came together at temporary villages near rivers and lakes, such as Lake Winnipesaukee at the Weirs.

The bands were also found along the seacoast for planting and fishing and in the Cowass meadows in Haverhill, New Hampshire.

There was peace among the Native Americans and early European settlers. The native tribes taught the early settlers the essentials to their survival in the new countryside. Their villages held everything as common property, like a large family. Their homes were often sixty to eighty feet long with a round roof, which was generally covered with movable matting. The natives sought to trade with the settlers for metal tools and utensils, blankets and weapons, both for hunting and resisting attacks from their enemy, the Mohawks.

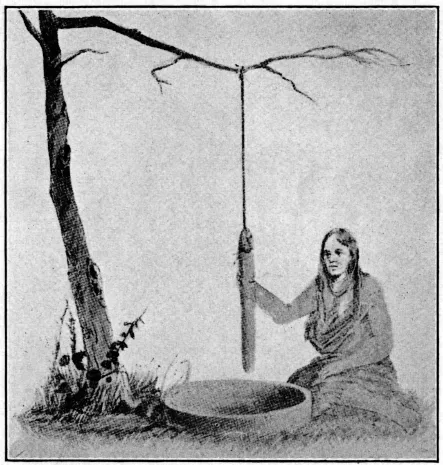

All the Abenaki tribes lived a lifestyle similar to the Algonquians of southern New England. They cultivated crops and located their villages near the fertile Pennacook land where fishing and hunting were plentiful. It was along the banks of the Merrimack and Connecticut Rivers in the rich soil that the Indians had their small patches of cultivated land where the women planted corn, pumpkins, squash, melons and beans. They always ground the corn and cooked it into cakes or made mush.

A typical primitive Indian mill. Courtesy of author.

When the corn was large enough, it was cut from the cob and boiled, which was known by the Indians as samp. When corn and beans were cooked together, the meal was called succotash. Their food was boiled in earthen pottery and placed on the fire. During the spring, the women tapped the maple trees and boiled the sap into a syrup in birch kettles.

They lived in scattered villages of families, and many villages had to be fortified, depending on the enemies of other tribes or Europeans near the village. Abenaki villages were quite small compared to those of the Iroquois.

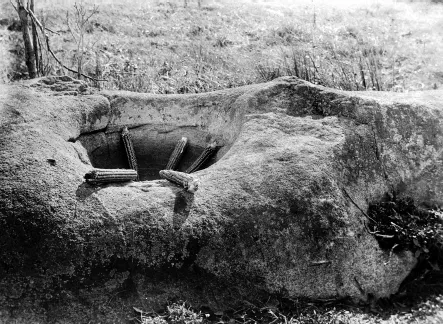

The old mortar. Photo courtesy by Mary Burleigh.

During the winter months, the Abenakis lived in small groups in dwellings of dome-shaped, bark-covered wigwams and a few oval-shaped longhouses. They would line the inside of their conical wigwams with bear skin for warmth.

The Abenakis were a farming people who supplemented their agriculture through hunting and fishing. G...