eBook - ePub

United States Army in WWII - Europe - the Ardennes: Battle of the Bulge

[Illustrated Edition]

- 762 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

United States Army in WWII - Europe - the Ardennes: Battle of the Bulge

[Illustrated Edition]

About this book

[Includes 14 maps and 96 photos]

During most of the eleven months between D-day and V-E day, the U.S. Army was carrying on highly successful offensive operations. As a consequence, the American soldier was buoyed with success, imbued with the idea that his enemy could not strike him a really heavy counterblow...Then, unbelievably, and under the goad of Hitler's fanaticism, the German Army launched its powerful counteroffensive in the Ardennes in Dec. 1944 with the design of knifing through the Allied armies and forcing a negotiated peace. The mettle of the American soldier was tested in the fires of adversity and the quality of his response earned for him the right to stand shoulder to shoulder with his forebears of Valley Forge, Fredericksburg, and the Marne.

This is the story of how the Germans planned and executed their offensive. It is the story of how the high command, American and British, reacted to defeat the German plan once the reality of a German offensive was accepted. But most of all it is the story of the American fighting man and the manner in which he fought a myriad of small defensive battles until the torrent of the German attack was slowed and diverted, its force dissipated and finally spent. It is the story of squads, platoons, companies, and even conglomerate scratch groups that fought with courage, with fortitude, with sheer obstinacy, often without information or communications or the knowledge of the whereabouts of friends...

In recreating the Ardennes battle, the author has penetrated "the fog of war" as well as any historian can hope to do. No other volume of this series treats as thoroughly or as well the teamwork of the combined arms-infantry and armor, artillery and air, combat engineer and tank destroyer-or portrays as vividly the starkness of small unit combat. Every thoughtful student of military history, but most especially the student of small unit tactics, should find the reading of Dr. Cole's work a rewarding experience.

During most of the eleven months between D-day and V-E day, the U.S. Army was carrying on highly successful offensive operations. As a consequence, the American soldier was buoyed with success, imbued with the idea that his enemy could not strike him a really heavy counterblow...Then, unbelievably, and under the goad of Hitler's fanaticism, the German Army launched its powerful counteroffensive in the Ardennes in Dec. 1944 with the design of knifing through the Allied armies and forcing a negotiated peace. The mettle of the American soldier was tested in the fires of adversity and the quality of his response earned for him the right to stand shoulder to shoulder with his forebears of Valley Forge, Fredericksburg, and the Marne.

This is the story of how the Germans planned and executed their offensive. It is the story of how the high command, American and British, reacted to defeat the German plan once the reality of a German offensive was accepted. But most of all it is the story of the American fighting man and the manner in which he fought a myriad of small defensive battles until the torrent of the German attack was slowed and diverted, its force dissipated and finally spent. It is the story of squads, platoons, companies, and even conglomerate scratch groups that fought with courage, with fortitude, with sheer obstinacy, often without information or communications or the knowledge of the whereabouts of friends...

In recreating the Ardennes battle, the author has penetrated "the fog of war" as well as any historian can hope to do. No other volume of this series treats as thoroughly or as well the teamwork of the combined arms-infantry and armor, artillery and air, combat engineer and tank destroyer-or portrays as vividly the starkness of small unit combat. Every thoughtful student of military history, but most especially the student of small unit tactics, should find the reading of Dr. Cole's work a rewarding experience.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access United States Army in WWII - Europe - the Ardennes: Battle of the Bulge by Dr. Hugh M. Cole in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & European History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Chapter I — The Origins

On Saturday, 16 September 1944, the daily Führer Conference convened in the Wolf's Lair, Hitler's East Prussian headquarters. No special word had come in from the battle fronts and the briefing soon ended, the conference disbanding to make way for a session between Hitler and members of what had become his household military staff. Wilhelm Keitel and Alfred Jodl were in this second conference. So was Heinz Guderian, who as acting chief of staff for OKH held direct military responsibility for the conduct of operations on the Russian front.

Herman Göring was absent. From this fact stems the limited knowledge available of the initial appearance of the idea which would be translated into historical fact as the Ardennes counteroffensive or Battle of the Bulge. Göring and the Luftwaffe were represented by Werner Kreipe, chief of staff for OKL. Perhaps Kreipe had been instructed by Göring to report fully on all that Hitler might say; perhaps Kreipe was a habitual diary-keeper. In any case he had consistently violated the Führer ordinance that no notes of the daily conferences should be retained except the official transcript made by Hitler's own stenographic staff.

Trenchant, almost cryptic, Kreipe's notes outline the scene. Jodl, representing OKW and thus the headquarters responsible for managing the war on the Western Front, began the briefing.{1} In a quiet voice and with the usual adroit use of phrases designed to lessen the impact of information which the Führer might find distasteful, Jodl reviewed the relative strength of the opposing forces. The Western Allies possessed 96 divisions at or near the front; these were faced by 55 German divisions. An estimated 10 Allied divisions were en route from the United Kingdom to the battle zone. Allied airborne units still remained in England (some of these would make a dramatic appearance the very next day at Arnhem and Nijmegen). Jodl added a few words about shortages on the German side, shortages in tanks, heavy weapons, and ammunition. This was a persistent and unpopular topic; Jodl must have slid quickly to the next item—a report on the German forces withdrawing from southern and southwestern France.

Suddenly Hitler cut Jodl short. There ensued a few minutes of strained silence. Then Hitler spoke, his words recalled as faithfully as may be by the listening OKL chief of staff. "I have just made a momentous decision. I shall go over to the counter-attack, that is to say"—and he pointed to the map unrolled on the desk before him—"here, out of the Ardennes, with the objective—Antwerp." While his audience sat in stunned silence, the Führer began to outline his plan.

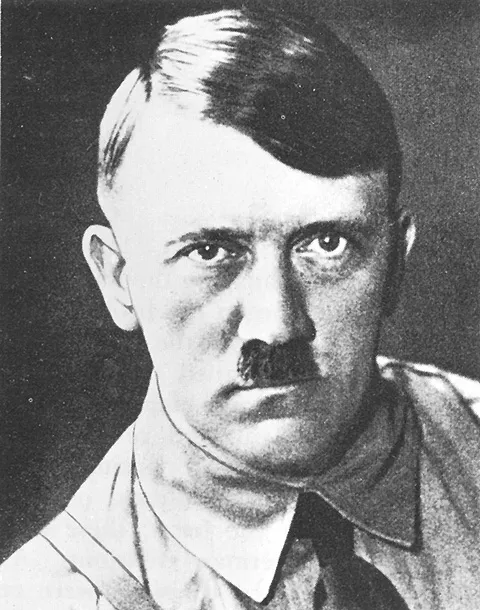

ADOLF HITLER

Historical hindsight may give the impression that only a leader finally bereft of sanity could, in mid-September of 1944, believe Germany physically capable of delivering one more powerful and telling blow. Politically the Third Reich stood deserted and friendless. Fascist Italy and the once powerful Axis were finished. Japan had politely suggested that Germany should start peace negotiations with the Soviets. In southern Europe, as the month of August closed, the Rumanians and Bulgarians had hastened to switch sides and join the victorious Russians. Finland had broken with Germany on 2 September. Hungary and the ephemeral Croat "state" continued in dubious battle beside Germany, held in place by German divisions in the line and German garrisons in their respective capitals. But the twenty nominal Hungarian divisions and an equivalent number of Croatian brigades were in effect canceled by the two Rumanian armies which had joined the Russians.

The defection of Rumanian, Bulgarian, and Finnish forces was far less important than the terrific losses suffered by the German armies themselves in the summer of 1944. On the Eastern and Western Fronts the combined German losses during June, July, and August had totaled at least 1,200,000 dead, wounded, and missing. The rapid Allied advances in the west had cooped up an additional 230,000 troops in positions from which they would emerge only to surrender. Losses in matériel were in keeping with those in fighting manpower.

Room for maneuver had been whittled away at a fantastically rapid rate. On the Eastern Front the Soviet summer offensive had carried to the borders of East Prussia, across the Vistula at a number of points, and up to the northern Carpathians. Only a small slice of Rumania was left to German troops. By mid-September the German occupation forces in southern Greece and the Greek islands (except Crete) already were withdrawing as the German grasp on the Balkans weakened.

On the Western Front the Americans had, in the second week of September, put troops on the soil of the Third Reich, in the Aachen sector, while the British had entered Holland. The German armies in the west faced a containing Allied front reaching from the Swiss border to the North Sea. On 14 September the newly appointed German commander in the west, Generalfeldmarschall Gerd von Rundstedt, acknowledged that the "Battle for the "West Wall" had begun.

On the Italian front Generalfeldmarschall Albert Kesselring's two armies retained position astride the Apennines and, from the Gothic Line, defended northern Italy. Here, of all the active fronts, the German forces faced the enemy on something like equal terms—except in the air. Nonetheless the Allies were dangerously close to the southern entrances to the Po Valley.

In the far north the defection of Finland had introduced a bizarre operational situation. In northern Finland and on the Murmansk front nine German divisions held what earlier had been the left wing of the 700-mile Finno-German front. Now the Finns no longer were allies, but neither were they ready to turn their arms against Generaloberst Dr. Lothar Rendulic and his nine German divisions. The Soviets likewise showed no great interest in conducting a full-scale campaign in the subarctic. With Finland out of the war, however, the German troops had no worthwhile mission remaining except to stand guard over the Petsamo nickel mines. Only a month after Mannerheim took Finland out of the war, Hitler would order the evacuation of that country and of northern Norway.

Political and military reverses so severe as those sustained by the Third Reich in the summer of 1944 necessarily implied severe economic losses to a state and a war machine fed and grown strong on the proceeds of conquest. Rumanian oil, Finnish and Norwegian nickel, copper, and molybdenum, Swedish high-grade iron ore, Russian manganese, French bauxite, Yugoslavian copper, and Spanish mercury were either lost to the enemy or denied by the neutrals who saw the tide of war turning against a once powerful customer.

Hitler's Perspective September 1944

In retrospect, the German position after the summer reverses of 1944 seemed indeed hopeless and the only rational release a quick peace on the best possible terms. But the contemporary scene as viewed from Hitler's headquarters in September 1944, while hardly roseate, even to the Führer, was not an unrelieved picture of despair and gloom. In the west what had been an Allied advance of astounding speed had decelerated as rapidly, the long Allied supply lines, reaching clear back to the English Channel and the Côte d'Azur, acting as a tether which could be stretched only so far. The famous West Wall fortifications (almost dismantled in the years since 1940) had not yet been heavily engaged by the attacker, while to the rear lay the great moat which historically had separated the German people from their enemies—the Rhine. On the Eastern Front the seasonal surge of battle was beginning to ebb, the Soviet summer offensive seemed to have run its course, and despite continuing battle on the flanks the center had relapsed into an uneasy calm.

Even the overwhelming superiority which the Western Allies possessed in the air had failed thus far to bring the Third Reich groveling to its knees as so many proponents of the air arm had predicted. In September the British and Americans could mount a daily bomber attack of over 5,000 planes, but the German will to resist and the means of resistance, so far as then could be measured, remained quite sufficient for a continuation of the war.

Great, gaping wounds, where the Allied bombers had struck, disfigured most of the larger German cities west of the Elbe, but German discipline and a reasonably efficient warning and shelter system had reduced the daily loss of life to what the German people themselves would reckon as "acceptable." If anything, the lesson of London was being repeated, the non-combatant will to resist hardening under the continuous blows from the air and forged still harder by the Allied announcements of an unconditional surrender policy.

The material means available to the armed forces of the Third Reich appeared relatively unaffected by the ceaseless hammering from the air. It is true that the German war economy was not geared to meet a long-drawn war of attrition. But Reich Minister Albert Speer and his cohorts had been given over two years to rationalize, reorganize, disperse, and expand the German economy before the intense Allied air efforts of 1944. So successful was Speer's program and so industrious were the labors of the home front that the race between Allied destruction and German construction (or reconstruction) was being run neck and neck in the third quarter which Hitler instituted the far-reaching military plans eventuating in the Ardennes counteroffensive.

The ball-bearing and aircraft industries, major Allied air targets during the first half of 1944, had taken heavy punishment but had come back with amazing speed. By September bearing production was very nearly what it had been just before the dubious honor of nomination as top priority target for the Allied bombing effort. The production of single engine fighters had risen from 1,016 in February to a high point of 3,031 such aircraft in September. The Allied strategic attack leveled at the synthetic oil industry, however, showed more immediate results, as reflected in the charts which Speer put before Hitler. For aviation gasoline, motor gasoline, and diesel oil, the production curve dipped sharply downward and lingered far below monthly consumption figures despite the radical drop in fuel consumption in the summer of 1944. Ammunition production likewise had declined markedly under the air campaign against the synthetic oil industry, in this case the synthetic nitrogen procedures. In September the German armed forces were firing some 70,000 tons of explosives, while production amounted to only half that figure. Shells and casings were still unaffected except for special items which required the ferroalloys hitherto procured from the Soviet Union, France, and the Balkans.

Although in the later summer of 1944 the Allied air forces turned their bombs against German armored vehicle production (an appetizing target because of the limited number of final assembly plants), an average of 1,500 tanks and assault guns were being shipped to the battle front every thirty days. During the first ten months of 1944 the Army Ordnance Directorate accepted 45,917 trucks, but truck losses during the same period numbered 117,719. The German automotive industry had pushed the production of trucks up to an average of 9,000 per month, but in September production began to drop off, a not too important recession in view of the looming motor fuel crisis.

The German railway system had been under sporadic air attacks for years but was still viable. Troops could be shuttled from one fighting front to another with only very moderate and occasional delays; raw materials and finished military goods had little waste time in rail transport. In mid-August the weekly car loadings by the Reichsbahn hit a top figure of 899,091 cars.

In September Hitler had no reason to doubt, if he bothered to contemplate the transport needed for a great counteroffensive, that the rich and flexible German railroad and canal complex would prove sufficient to the task ahead and could successfully resist even a coordinated and systematic air attack—as yet, of course, untried.

In German war production the third quarter of 1944 witnessed an interesting conjuncture, one readily susceptible to misinterpretation by Hitler and Speer or by Allied airmen and intelligence. On the one hand German production was, with the major exceptions of the oil and aircraft industries, at the peak output of the war; on the other hand the Allied air effort against the German means of war making was approaching a peak in terms of tons of bombs and the number of planes which could be launched against the Third Reich.{2} But without the means of predicting what damage the Allied air effort could and would inflict if extrapolated three or six months into the future, and certainly without any advisers willing so to predict, Hitler might reason that German production and transport, if wisely husbanded and rigidly controlled, could support a major attack before the close of 1944. Indeed, only a fortnight prior to the briefing of 16 September Minister Speer had assured Hitler that German war stocks could be expected to last through 1945. Similarly, in the headquarters of the Western Allies it was easy and natural to assume the thousands of tons of bombs dropped on Germany must inevitably have weakened the vital sections of the German war economy to a point where collapse was imminent and likely to come before the end of 1944.

Hitler's optimism and miscalculation, then, resulted in the belief that Germany had the material means to launch and maintain a great counteroffensive, a belief nurtured by many of his trusted aides. Conversely, the miscalculation of the Western Allies as to the destruction wrought by their bombers contributed greatly to the pervasive optimism which would make it difficult, if not impossible, for Allied commanders and intelligence agencies to believe or perceive that Germany still retained the material muscle for a mighty blow.

Assuming that the Third Reich possessed the material means for a quick transition from the defensive to the offensive, could Hitler and his entourage rely on the morale of the German nation and its fighting forces in this sixth year of the war? The five years which had elapsed since the invasion of Poland had taken heavy toll of the best physical specimens of the Reich. The irreplaceable loss in military manpower (the dead, missing, those demobilized because of disability or because of extreme family hardship) amounted to 3,266,686 men and 92,811 officers as of 1 September 1944.{3} Even without an accurate measure of the cumulative losses suffered by the civilian population, or of the dwellings destroyed, it is evident that the German home front was suffering directly and heavily from enemy action, despite the fact that the Americans and British were unable to get together on an air campaign designed to destroy the will of the German nation. Treason (as the Nazis saw it) had reared its ugly head in the abortive Putsch of July 1944, and the skeins of this plot against the person of the Führer still were unraveling in the torture chambers of the Gestapo.

Had the Nazi Reich reached a point in its career like that which German history recorded in the collapse of the German Empire during the last months of the 1914-1918 struggle? Hitler, always prompt to parade his personal experiences as a Frontsoldat in the Great War and to quote this period of his life as testimony refuting opinions offered by his generals, was keenly aware of the moral disintegration of the German people and the armies in 1918. Nazi propaganda had made the "stab in the back" (the theory that Germany had not been defeated in 1918 on the battlefield but had collapsed as a result of treason and weakness on the home front) an article of German faith, with the Führer its leading proponent. Whatever soul-searching Hitler may have experienced privately as a result of the attempt on his life and the precipitate retreats of his armies, there is no outward evidence that he saw in these events any kinship to those of 1918.

He had great faith in the German people and in their devotion to himself as Leader, a faith both mystic and cynical. The noise of street demonstrations directed against himself or hi...

Table of contents

- Title page

- TABLE OF CONTENTS

- MAPS

- ILLUSTRATIONS

- DEDICATION

- FOREWORD

- THE AUTHOR

- PREFACE

- Chapter I - The Origins

- Chapter II - Planning the Counteroffensive

- Chapter III - Troops and Terrain

- Chapter IV - Preparations

- Chapter V - The Sixth Panzer Army Attack

- Chapter VI - The German Northern Shoulder Is Jammed

- Chapter VII - Breakthrough at the Schnee Eifel

- Chapter VIII - The Fifth Panzer Army Attacks the 28th Infantry Division

- Chapter IX - The Attack by the German Left Wing - 16-20 December

- Chapter X - The German Southern Shoulder Is Jammed

- Chapter XI - The 1st SS Panzer Division's Dash Westward, and Operation Greif

- Chapter XII - The First Attacks at St. Vith

- Chapter XIII - VIII Corps Attempts To Delay the Enemy

- Chapter XIV - The VIII Corps Barrier Lines

- Chapter XV - THE GERMAN SALIENT EXPANDS TO THE WEST

- Chapter XVI - The Threat Subsides; Another Emerges

- Chapter XVII - St. Vith Is Lost

- Chapter XVIII - The VII Corps Moves To Blunt the Salient

- Chapter XIX - The Battle of Bastogne

- Chapter XX - The XII Corps Attacks the Southern Shoulder

- Chapter XXI - The III Corps' Counterattack Toward Bastogne

- Chapter XXII - The Battle Before the Meuse

- Chapter XXIII - The Battle Between the Salm and the Ourthe 24 December-2 January

- Chapter XXIV - The Third Army Offensive

- Chapter XXV - Epilogue

- REQUEST FROM THE PUBLISHER

- Appendix A - Table of Equivalent Ranks

- Appendix B - Recipients of the Distinguished Service Cross

- Bibliographical Note

- Glossary

- Basic Military Map Symbols