- 128 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

Journalist and historian Chuck McShane traces the triumphs and troubles of Lake Norman from the region's colonial beginnings to its modern incarnation.

On a muggy September day in 1959, North Carolina governor Luther Hodges set off the first charge of dynamite for the Cowan's Ford Dam project. The dam channeled Catawba River waters into the largest lake in North Carolina: Lake Norman. The project was the culmination of James Buchanan Duke's dream of an electrified South and the beginning of the region's future. Over the years, the area around Lake Norman transformed from a countryside of cornstalks and cattle fields to an elite suburb full of luxurious subdivisions and thirty-five-foot sailboats.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access A History of Lake Norman by Chuck McShane in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & Development Economics. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

THE CATAWBA AND ITS PEOPLE

Before the lake there was the river. Approimately 320 miles of slow-flowing water trickling from the cool springs of Mount Mitchell, North Carolina, down to the hot, sandy valleys of the South Carolina midlands. There, the Catawba-Wateree converges with the Conagree. Together, they become the Santee, which meanders 100 miles more through swamp and bald cypress, into the Atlantic, somewhere between Charleston and Myrtle Beach. The Catawba was never a grand river—neither very broad nor particularly deep. In later years, even smaller ships would find the river impossible to navigate. But for the group of Native American tribes who found it first, perhaps six hundred years ago, its waters would do just fine. The river was so important to the tribes living in the area that they called themselves Kawahcatawba, meaning “the people of the river.” The Kawahcatawba were less of a tribe and more of a loose federation of smaller, related settlements living in several villages that formed a linear band on either side of the river. There, they took advantage of the rich bottomland—a rare, fertile crescent in the otherwise rocky and clay-filled Piedmont region. They lived in small, bark-covered homes with rounded roofs and grew corn, squash and beans in fields nearby. The men used canoes to fish in the river and hunted passenger pigeons with three-foot-long blowguns. Warfare was common, and they stood guard against potential encroachment from the Cherokee, whose lands bumped up against Catawba territory in the west. Catawba mothers flattened their infant sons’ heads so that they would look more threatening when they grew into men and warriors.

European explorers arrived early. In the mid-1500s, Hernando de Soto passed nearby on his quest for gold. Twenty years later, Juan Pardo and his men established several forts near the Indian villages. The largest of these forts was probably Joara, near present-day Morganton. About twenty Spanish soldiers lived in Joara for about eighteen months in the 1560s. Eventually, the tribes tired of the arrangement and killed off all but one Spaniard. It would be almost two hundred years before permanent white settlers returned to the region, though traveling traders from France and England often lived among the Catawba. The Catawba tribe was known for its pottery bowls, baskets and mats. Those goods proved valuable bartering currency, but trade with Europeans was deadly to many Catawba. Though the Catawba had, by the early 1700s, allied themselves with the British who were beginning to populate the eastern reaches of the state, alliances did not inoculate them from disease. Almost half of the tribes’ estimated five thousand members perished in the 1738 smallpox epidemic. Their villages stood abandoned and rotting. By 1780, only five hundred Catawba remained.

The River and the Great Wagon Road

White settlers started arriving in the late 1740s. Scots-Irish families mostly, but some Germans came as well. They had been priced out of the increasingly crowded valleys of Pennsylvania and Maryland. They were tired, too, of the long reach of the Anglican Church, which demanded taxes and fees to record marriages and feed their clergy. Many Scots-Irish had little use for religion, and those who did were Presbyterian. Neither wanted anything to do with the Anglicans, and they resented paying fees to support them. One Anglican itinerant minister received an angry welcome to Mecklenburg County in the 1760s. A group of Scots-Irish settlers chased him away, saying they wanted no “Damned Black Gown Sons of Bitches” near their settlement.

A mile west of the Catawba River, in what would become Catawba County, Adam Sherrill built one of the first permanent European homes here, most likely a simple log structure, near a ford (a shallow and narrow spot in the river good for crossing). As more settlers arrived from the North, Sherrill’s Ford and other crossings connected the loosely settled landscape. On the eastern side, and farther south, the Torrences, the Jettons and the Pottses farmed wheat and corn and raised hogs and cattle. Life centered on two institutions: the churches and the crossroads taverns. Most people grew what they ate and sold what they couldn’t. The farmers would turn any extra corn or peaches into liquor to get use out of them before they spoiled.

After a long trip down through the Appalachian Valley on the muddy and rocky Great Wagon Road, the settlers found what they were looking for: fertile land where they could be left alone.

They wouldn’t be left alone for long, though. The settlers here had never been friendly with the British colonial authorities. So, when news reached the area that British soldiers had fired on a Massachusetts militia in 1775, it didn’t take much convincing for the Catawba River settlers to support the revolution against the British. Some joined militia units or Continental army regiments and set off to the battles in the North. The war stayed far to the north for its first years. However, the Catawba area would not be spared. During the British southern campaign, in late 1780, the British passed over the Catawba several times. In January 1781, local militia and soldiers who were camped out near Cowan’s Ford heard news of British forces approaching the river from the southwest. Early on the morning of February 1, the British troops reached Cowan’s Ford and charged across the deep wagon ford. Several British horses drowned, and the American militia picked off a handful of British soldiers. The five thousand redcoats proved too much for the nine hundred ragged colonials; the British overpowered the colonials, who scattered east along the muddy road to Salisbury. General William Davidson was killed in the battle, shot through the heart with a rifle bullet. The next day, British troops led by Banastre Tarleton reached Torrence’s Tavern, near present-day Mount Mourne, where many colonial militiamen had retreated to regroup. Tarleton caught the colonials by surprise. When Tarleton and the redcoats arrived at the tavern, they chased the colonials, many of them drunk and carrying flasks of whiskey, out of the tavern. Then, Tarleton burned the tavern to the ground and destroyed the militia’s camp nearby.

A Revolutionary War memorial to General William Lee Davidson near the Cowan’s Ford Dam. Davidson died during the Battle of Cowan’s Ford on February 1, 1781. Courtesy of the Charlotte Observer.

War to War

The British won the battles along the Catawba, but the chase through the Carolinas weakened the British forces. The broken redcoats would soon surrender to General George Washington in Yorktown, Virginia. Back in the communities around the river fords, life returned to normal in the newly formed nation. On the Lincoln County side of the Catawba, a handful of iron forges sprung up, taking advantage of local iron ore deposits to make weapons and other manufactued goods. For the most part, people farmed. Corn and wheat were the primary crops, but more and more farmers began planting cotton. The cotton gin, introduced in the 1790s, had made cotton production easier and more profitable. Cotton sales brought prosperity to a handful of families around the river, and they poured much of their wealth into large plantation homes, like Latta Place and Beaver Dam and Mount Mourne. As historian Mary Kratt notes, “The people of northern Mecklenburg regarded themselves as the patricians of the county.” Like the rest of the South, most of that wealth was made on the backs of the slaves who worked the cotton fields. Major Rufus Reid named the plantation he built in the early 1830s, in southern Iredell County, Mount Mourne, after the picturesque Mourne Mountains in the north of Ireland. The name took on a different meaning for the slaves who often saw their families for the last time as they were bought and sold there.

Slaves also made the bricks of the buildings at Davidson College, which opened in 1837 as a Presbyterian alternative to the increasingly secular public university in Chapel Hill, 130 miles to the northeast. William Lee Davidson II, the son of the general killed at Cowan’s Ford, donated the land for the college. In time, a small village would spring up around the college, eventually becoming a commercial center for the rural area and a stagecoach stop along the road from Charlotte to Salisbury and Lincolnton. In heavy rain, the main road in front of campus became nearly impassable. The often-rowdy Davidson students nicknamed the road the “Red Sea” in wet weather.

The Catawba River’s purpose was clear then. Its waters were for fish and its banks for rich farmland. As the cotton economy boomed in the 1840s and ’50s, local plantation owners and wealthy North Carolinians saw different possibilities for the river. In Lincoln County, the mineral springs near Denver attracted vacationers and health seekers. In 1824, geology professor Dennis Olmsted recommended the springs as a cure for liver disease and chronic fatigue. A small hotel had operated there since the 1790s, but the new popularity of mineral springs brought bigger crowds than it could house. In 1838, Joseph Hampton expanded the Catawba Springs hotel to one hundred rooms. Guests arrived on the Salisbury-to-Asheville stagecoach line or in their private wagons. On weekends, Davidson College students swam in the springs and held large parties in the ballroom. The hotel would not survive the Civil War, though, as the cotton planters’ wealth faded. Later on, the growth of railroads made more exotic and faraway destinations easier to reach.

The Atlantic, Tennessee and Ohio Railroad cut through the area that would become Lake Norman in 1860. Despite its ambitious name, the railroad would only ever make it the forty or so miles from Charlotte to Statesville. At the height of the Civil War, in 1863, the cash-strapped Confederate government tore up the lines to use them for more critical supply routes. Civil War battles avoided the Catawba, except for a brief crossing by Stoneman’s Raiders near Nations Ford, far to the south of the area that would become Lake Norman. But no area remained entirely isolated from the war’s effects. Farmers sent their sons off to battle. Davidson College was mostly empty, its older students off fighting in Confederate brigades. With blockades and torn-up railroad tracks, costs for daily necessities skyrocketed. Coffee and sugar were so rare that, in Davidson at least, they were reserved for only injured soldiers and the very elderly. In town, Davidson student Dandridge Burwell remembered, “only one store was open, next to nothing in it.”

Bringing the Mills to the Cotton

The lack of major Civil War battles left the Catawba River region relatively unscathed and ready to take advantage of returning postwar prosperity. The Southern economy had long lagged behind the rest of the nation in terms of industrialization. Though some cities, such as Charlotte, supported minor industry, there were no grand factories here. The aftermath of war made the situation worse. Some Southern towns lay in ruins, and refugees from the countryside poured into unaffected cities like Charlotte, which had emerged as a railroad hub. In northern Mecklenburg, the destroyed train tracks wouldn’t start running again until the 1870s.

Though blacks had gained their freedom with the end of the Civil War, many stayed in the area as tenant sharecroppers—a system that, economically at least, resembled slavery. Cotton remained a cash crop. Many made the two-day trek to Charlotte with their wagonloads of cotton, camping along the muddy roadside. In northern Mecklenburg County, the market town of Davidson and an upstart cotton merchant, R.J. Stough, competed for those farmers’ business. Providing scales for weighing and shipping, Stough’s shop, one mile south of Davidson’s town limits, would later grow into the town of Liverpool, the site of present-day Cornelius.

As it turned out, there would be enough business for both towns. Demand for cotton only increased after the textile mill boom of the 1880s. Southern industrialists took advantage of the cheaper labor in the South, while avoiding the often-humiliating and usurious process of getting credit from northern financiers. Charlotte, with its railroad connections in all directions, would become the epicenter of the textile push. Some mills would rise in the growing railroad town, but most set up shop outside the city limits. Mill owners built most intensely in rural areas, along riverbanks where water power was plentiful. It was easy to recruit the impoverished migrant farmers from the isolated Appalachian Mountains to work in such semi-rural places. It was easier to control them there, too.

The rushing waters of the hilly terrain on the border of Catawba and Lincoln Counties proved a good spot to take advantage of water power. A textile mill had operated there since the early 1850s, on a mile-long stretch of island in one of the river’s wider spots. In 1881, brothers Columbus and Wilfred Turner of Iredell County bought the old mill and set out to increase production. A few miles south, Columbus built a house on a hillside overlooking the river, near another cotton mill and company store. Turner named the house Mont Beaux, French for “beautiful mountain.” When the millworkers began to pronounce the name of the place as “Monbo,” the Turners embraced the name and established the Monbo Mill Company. In the late 1880s, the Turners sold the Long Island Mill. The brothers turned their focus to building their business at the Monbo Mill, whose machinery was powered by a small log dam and a water wheel.

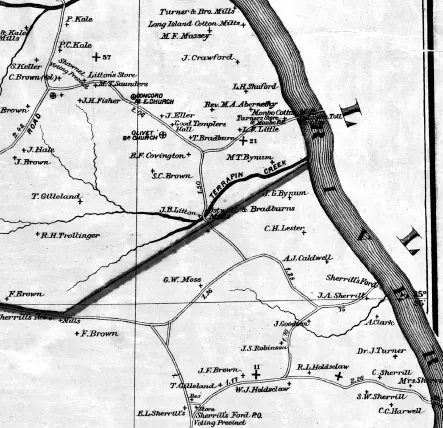

A map of the Catawba River area near the Monbo and Long Island Mills in 1896. Courtesy of the State Archives of North Carolina.

Residents of mill villages describe them as communal places, where families looked out for one another. But there was a dark side to mill life, too. Mill companies built houses, which they rented to the workers; stores, whose customers were almost exclusively millworkers; and often hired their own security forces to watch out for any workers getting out of line. Mill villages could be rough places. Jim Brown found that out one night in 1894. Brown, a recently arrived English businessman, had bought the mill from the Turners a few years before. He stopped by the company store one night to check on something. There, he found an employee—a man named Covington—trying to rob the store. The startled Covington shot and killed Brown. Millworkers and others from throughout the county packed the courthouse in Newton for Covington’s trial and subsequent hanging.

Jim Brown’s son, Osborne, took over after his death and set about expanding the Long Island Mill with new buildings and machinery. The early 1900s were a good time for mill owners. Labor was cheap, cotton prices were reasonable and demand for cloth was high. Countless mills popped up throughout the region. In Monbo, the Turner brothers expanded across the river to Iredell County and built a second mill and village called East Monbo. In 1910, the brothers replaced the old wooden dam that reached halfway across the river to Goat Island—named for the herd of wild goats that lived there—with a solid concrete dam stretching from bank to bank. Business would only get better with the beginning of World War I. Soldiers needed cotton uniforms and wool blankets to keep warm in cold European fields.

“Buck” Duke and the Electric River

James Buchanan “Buck” Duke was a wealthy man. He had built his father’s fledgling Durham, North Carolina tobacco company into a national powerhouse. Anyone who used tobacco around the turn of the twentieth century—and lots of people did—added to Duke’s wealth with each puff or chaw. Duke was successful because he embraced new technologies and was marketing savvy. He cornered the market on the Bonsack rolling machine, which put immigrant hand-rollers in New York City out of work but meant his American Tobacco Company could make cigarettes much faster than competitors and sell them for much cheaper. He was also an early pioneer of vertical integration—the business strategy of owning as many links in the supply chain as possible. More visible to the everyday American, Duke’s companies also invested heavily in advertising. Brightly colored ads for Duke’s Cameo cigarettes filled general store shelves and warehouse walls. It was a successful plan—so successful that by 1890, 90 percent of all cigarettes sold in the United States were made by the American Tobacco Company and its subsidiaries. The plan was so successful that in 1911, the U.S. Supreme Court ordered Duke’s American Tobacco Company dissolved for violating antitrust laws.

James “Buck” Duke on the Atlantic City, New Jersey boardwalk in 1924. Courtesy of Duke University Archives.

Duke could have retired with his millions to his Fifth Avenue mansion on New York’s Upper East Side or t...

Table of contents

- Front Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Contents

- Preface

- Acknowledgements

- Introduction

- 1. The Catawba and Its People

- 2. Electric River: The Flood of 1916 and Southern Power

- 3. The Cowan’s Ford Dam: A Project for Its Time

- 4. The Expressway to Prosperity

- 5. Growing Pains: Becoming a Suburb

- 6. The Lore of the Lake: Tall Tales and Future Challenges

- Afterword

- Bibliography

- About the Author