- 160 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

The Maritime Marauder of Revolutionary Maine: Captain Henry Mowat

About this book

In 1775, Captain Henry Mowat infamously ordered the burning of Falmouth--now Portland. That act cast him as the arch-villain in the state's Revolutionary history, but Mowat's impact on Maine went far beyond a single order. The Scottish Mowat began his North American career by surveying the Maine coast, capturing and confiscating colonial merchant ships he suspected of smuggling. Already feared by Mainers when the war broke out, his legacy was further tarnished when he was blamed for dismantling Fort Pownall at the mouth of the Penobscot River. In this volume, local historian Harry Gratwick examines the life of Henry Mowat and whether he truly was the scoundrel of Revolutionary Maine.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access The Maritime Marauder of Revolutionary Maine: Captain Henry Mowat by Harry Gratwick in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & Early American History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Chapter 1

The Scottish Sailor

It is better to go to jail than to go to sea. At least in jail you are not apt to be drowned.

—Samuel Johnson

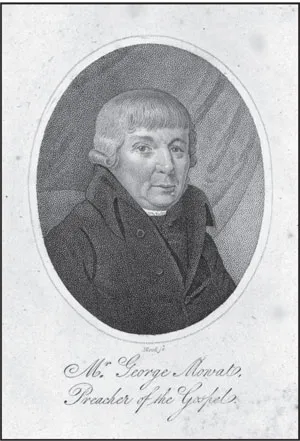

George Mowat was a minister and a cousin of Henry Mowat who lived in New Brunswick, Canada, in the mid-nineteenth century. Courtesy of the Maine Historical Society.

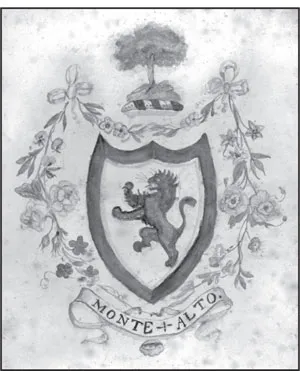

As noted, the origins of the Mowat name can be traced back to Normandy stemming from the surname Monhaut or, in Latin, de Monte Alto. In researching the origins of the family, David R. Jack wrote the following description in 1908: “In the hallway of the residence of Mr. George Mowat at Beech Hill near St. Andrews, New Brunswick, hangs a small frame containing the family coat of arms.” The crest is an oak tree growing out of a rock. Below is the motto “Monte Alto,” meaning on a high mountain. The crest in the Mowat hallway is similar to the one in Fairbairn’s Crests of Great Britain.

The Mowat family crest. Courtesy of the Maine Historical Society.

The first member of the Mowat family to arrive in Scotland was Robert de Montealto, who came from Wales in the twelfth century. His family had moved there after an ancestor had accompanied William the Conqueror. Robert de Montealto is believed to have come at the invitation of the Scottish king David I (1124–1153).

The Mowat family’s power and prestige increased during the reign of William the Lion (1165–1214) when William de Montetalto was granted the Lordship of Ferne in Angus. A branch of the family eventually moved on from this area in northeastern Scotland to the Orkney Islands, where Henry Mowat was born in 1734.

Henry Mowat grew up in the village of Stromness on the Orkney Islands. Courtesy of Wikipedia.

The Neolithic stone circle at Brodgar near Stromness continues to attract tourists. Courtesy of Wikipedia.

In the realm of folklore, there are still a few souls who persist in supporting the idea that the origins of the Mowat family in Scotland were Spanish. Their belief was that the Orkney Mowats were descended from a Spanish nobleman whose ship was wrecked following the defeat of the Armada in 1588. Although a good tale, historically it is apocryphal.

The nearest of the storm-swept Orkney Islands lies twelve miles off the northern coast of Scotland, and it was here that Henry Mowat was born in the village Stromness. The hamlet lies high on a bluff above the great naval anchorage of Scapa Flow. The lands around Stromness have changed little since Henry Mowat’s time. The ruins of the bishop’s palace still lie across the road from the great red sandstone of St. Magnus Cathedral. Nearby, the massive Neolithic stone circle at Brodgar and the tomb at Maeshowe, erected at the time of the pyramids, still attract tourists.

At one time, the Orkney Islands resounded with the Mowat name, although it is now nearly forgotten. In the cemeteries of Stromness and nearby Kirkwell, Mowat gravestones appear frequently, for the name was among the most illustrious in the island’s history. In the Jacobite rising of 1715 by James Francis Edward Stuart, the family backed the wrong side. Unfortunately for his followers, the “Old Pretender” failed in his attempt to regain the British throne.

As a result, the family had lost their lands and titles by the time Henry Mowat was born. His grandfather was incarcerated for debt, and his father spent his much of his life struggling against the load of bonds and obligations. Therefore, the birth of a son to Lieutenant Patrick Mowat of the Royal Navy received little notice. For an Orcadian boy whose ancestors had included a bishop and an admiral, it was an inauspicious beginning.

Young Henry and his three younger brothers grew up hearing tales of Francis Drake and the Spanish Armada. With a father who was an officer in the Royal Navy (he accompanied Captain Cook on his Pacific explorations) and a deceased uncle who had been an admiral, the boys’ future was preordained.

As noted, however, there was a problem. Patrick Mowat’s side of the family was tainted politically as well as impoverished. Even in the best of times, obtaining a commission in the Royal Navy required a powerful patron willing to post a boy to a midshipman’s billet for a substantial sum. Although he would eventually command a ship in the Royal Navy, Patrick Mowat’s rank as a lieutenant meant he did not have the clout or finances to open any of these doors, and these were not the best of times.

For Henry, however, there was an alternative. The Royal Navy in the eighteenth century was woefully lacking in competent officers. Thus the navy turned to the professional merchant marine or the maritime “underclass” to sail and maintain the ships of their great fleets. The bulk of these navy men were recruited, or “seized,” from the merchant marine. Indeed, fortunate was the Royal Navy captain who had merchant marine officers under his command.

Patrick Mowat’s four sons received a better than average education at Stromness schools, where they developed skills in writing, grammar and mathematics. It was in school that Henry would exhibit the stubborn streak that was to last throughout his life. We do not know about his brothers’ academic achievements, but Henry was an enterprising student who made an important decision as he neared the end of his formal education. (Little else is known about his brothers except that they also joined the navy and presumably became officers. All three were killed in naval actions in the Caribbean in the 1790s.)

Through his father’s limited connections, Henry was able to obtain a berth aboard a local merchant vessel. For more than three years, the young man learned navigation and seamanship under the guidance of an experienced ship’s master. Henry showed a flair for leadership and might well have expected promotion to mate and the probability of becoming a ship’s master in the merchant marine at an early age. It was here, however, that he demonstrated the stubbornness that would characterize his career. Henry told his father that he would be leaving the merchant marine and intended to become an officer in the Royal Navy.

Armed with an introductory letter from the captain of the merchant ship attesting to his excellent service, as well as one from his father who was now Captain of HMS Dolphin, Henry Mowat headed for the great British naval base at Portsmouth. It was here that he hoped to meet Captain Clark Gayton of HMS Antelope. With hat in hand, he presented himself to the officer of the deck.

The conversation might have gone something like this. “Sir, I am here to volunteer and I have two letters for Captain Gayton.” The officer probably gaped at the respectful young man. (Remember, this was an age when sailors were normally pressed into the navy against their will and here was a youth who actually wanted to volunteer.) Within an hour, Henry Mowat had received the “King’s shilling” (a signing bonus) and was enrolled as an able-bodied seaman in the Royal Navy. Thus the enterprising Mowat joined the British Navy in the spring of 1755 at the age of twenty-one.

Here we might pause and reflect on the Samuel Johnson quote cited at the beginning of the chapter: “It is better to go to jail than to sea. At least in jail you are not apt to be drowned.” Of course, many men did enlist in the Royal Navy, particularly if the alternative was jail. Those who did so almost immediately regretted their decision. The greatest number of “recruits” was impressed. A more accurate term might be “shanghaied” in that they were snatched from the street or from other merchant ships. The almshouses and courts were also handy resources. A Royal Naval vessel refused no one.

Many recruits were boys, too young to be common seamen, who were relegated to the worst jobs aboard ship. As new crewmembers, their life was brutal, characterized by barbarous discipline. The pay was low, the food miserable and there was no chance to go ashore. Leave was determined solely at the discretion of the captain.

These conditions notwithstanding, young Mowat had no choice but to take this route if he was to follow his dream. Captain Gayton of HMS Antelope would determine his immediate future. With his seagoing experience and good education, the new recruit was not just another seaman and the crew soon realized this. Although he was a new hand, Mowat was not subject to the usual harassment from his shipmates, who knew that within a few months, he would become their superior.

It soon became evident that Mowat would be “rated” (a petty officer) and carry the rattan “starter” (a cane or switch) of a master’s mate. Indeed, five months later, in November 1755, he was transferred from Antelope to HMS Chesterfield where he served for the next two years as a master’s mate until 1757. Aboard the British battleship of the day, known as a ship of line, the master and his mates were directly subordinate to the first lieutenant, who was the ship’s executive officer.

In reality, it was the master who ran the ship, and there was little for which he was not responsible. This ranged from the sailing, navigation and upkeep of the vessel to maintaining the ship’s stores and even the writing of the log. Needless to say, the bulk of this work was performed by several of HMS Chesterfield’s master’s mates, one of whom, for two years, was Henry Mowat.

The multitude of tasks and responsibilities for the master’s mates created a practical, hands-on experience for these men. It was a seagoing trade school offering instruction in all the skills expected, but seldom found, among the regularly commissioned “gentleman” officers. It also provided an introduction to the Royal Navy with all of its rules, regulations and paperwork for the proper conduct of a ship and its company. John Flint, a former merchant marine officer, tells us, “It is a sad commentary on the Royal Navy that it rarely reaped the benefits of commissioning these men who were so superbly trained.” They didn’t fit the image of the “officer class.” Henry Mowat, however, would be an exception.

When Mowat was appointed a midshipman in the Royal Navy and transferred to HMS Chesterfield in 1755, he had taken the all-important first step into the officer class. Midshipmen, however, were neither fish nor fowl. Most were appointed by senior admiralty figures and entered the service as boys between the ages of twelve and fourteen. Their quarters below decks were dark and dirty, a shadow world above the bilges, lit by tallow candles but supplied with an ample amount of rum.

Midshipmen were the most junior officers, with authority only over the common seaman. They shared their quarters with many others: older midshipmen, master’s mates and assorted ship’s clerks. Many of these were middle-aged men unlikely ever to become officers. All were at the beck and call of ship’s officers and the ship’s master. It was a rough and ready existence filled with hazing, beating and bullying, but it was the route the prospective young officer was expected to take.

An eighteenth-century naval battle between England and France, similar to the one in which Henry Mowat was involved in 1756. Courtesy of Wikipedia.

Henry Mowat entered this world when he went aboard HMS Antelope, and it continued when he was transferred to HMS Chesterfield. Even with his merchant marine background and his father’s reputation, Mowat’s advancement was not automatic. He did, however, have several advantages. He was older than most of the youthful midshipmen, he was an experienced mariner and, compared to many of his shipmates, he was an educated man who, according to reports, carried himself with a certain bearing.

With a senior officer acting as their instructor, Henry and other midshipmen would have studied composition as well as learned the routine, customs and traditions of the Royal Navy. As a dogsbody (a drudge) to the ship’s officers, Mowat would also have polished his navigation, gunnery, signal and leadership skills. On occasion, he would have been coxswain of the captain’s gig (launch), all the while taking verbal abuse from the commissioned officers, who had all undergone the same hell.

We know that Midshipman Mowat saw action aboard HMS Chesterfield in May 1756. The forty-four-gun frigate was a member of the British force involved in a major naval engagement with the French during the Seven Years’ War. The fleet was under the command of Admiral John Byng and was badly beaten off the island of Minorca in the Mediterranean Sea. Following the defeat, Admiral Byng was relieved of command. He was subsequently court-martialed and found guilty for “failing to do his utmost” to prevent Minorca falling to the French. Public indignation was so great that the unfortunate Byng was sentenced to death and executed by firing squad in 1757.

British admiral Byng was executed for having lost the battle of Minorca. Courtesy of Wikipedia.

Moving to HMS Ramilles in August 1757, Henry Mowat would prove his abilities frequently to the officers and captain of that venerable old warship. (It was originally launched in 1664 and rebuilt in 1706.) It was no great surprise, therefore, when he passed his lieutenant’s exam on May 9, 1758. The certificate of his “passing” by the admiralty noted:

He produceth journals kept by himself in Ches...

Table of contents

- Front Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Dedication

- Contents

- Foreword, by George Daughan

- Acknowledgement

- Introduction

- 1. The Scottish Sailor

- 2. HMS Canceaux and the Atlantic Neptune Project

- 3. The Revolution Begins in Maine

- 4. The Burning of Falmouth

- 5. Interlude: 1776 to 1779

- 6. The Expedition to the Penobscot

- 7. Last Years: 1783 to 1798

- Appendix. Henry Mowat’s Service Record in the Royal Navy

- Bibliography

- About the Author