![]()

LETTERS

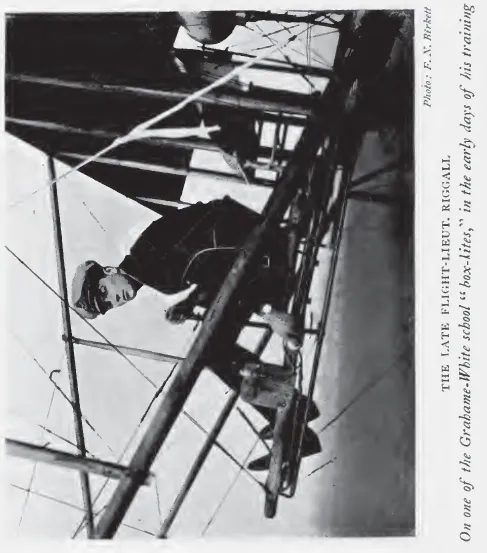

I—TRAINING

I

To his Father.

The Blue Bird, Brooklands Aerodrome,

Weybridge.

11th August, 1914.

DEAR DAD,

Am getting on famously and having a most amusing time. After I wrote you yesterday I went out and had my first lesson. Mr. Stutt, our instructor [for the British and Colonial Aeroplane Co.], sits immediately behind you, controls the engine switch and covers your hand on the stick. He took me straight up two or three hundred feet and then volplaned down. He always does this with new pupils to see how they take it. I think I managed to pass the ordeal all right. I had two or three flights backwards and forwards, and then another turn later on in the evening. Stutt is an awfully nice fellow, very small but very capable. On all sides one hears him recommended. When in the air, he bawls in your ear, “Now when you push your hand forward, you go down, see!“ (and he pushes your hand forward and you make a sudden dive), “ and when you pull it back you go up, and when you do this, so and so happens,” and so with everything he demonstrates. Then he says, “If you do so and so, you will break your neck, and if you try to climb too quickly you will make a tail slide.” It’s awfully hard work at first and makes your arm ache like fun. The school machines are very similar to the Grahame-Whites. You sit right in front, with a clean drop below you. We never strap ourselves in. The machines are the safest known, and never make a clean drop if control is lost, but slide down sideways.

When it got too dark we went in and had dinner, all sitting at the middle table. Could get no one to fetch my luggage, so decided to go myself after dinner. Unfortunately, I attempted a short cut in the dark and lost my way. After stumbling round the beastly aerodrome in the dark for an hour, I eventually got back to my starting point. I was drenched to the knees, and the moon didn’t help me much on account of the thick mist. It was about 10.30 p.m., so I gave up my quest; the prospect of the long walk and heavy bag was too discouraging.

I turned in in my vest and pants and had a good night. Was knocked up at 4.30 this morning and crawled gingerly into my still wet clothes. A lovely morning, very cold, and it was not long before I got wetter still, as the grass was sopping. Had two more lessons this morning, of about 15 minutes each, and took both right and left hand turns, part of the time steering by myself. Stutt says I am getting on. The machines are so stable that they will often fly quite a long way by themselves. Am now quite smitten, and if weather continues fine, I shall take my ticket in a week or ten days. Hope to be flying solo by Thursday or Friday. Experienced my first bump this morning. While flying at 200 feet, the machine suddenly bumped{1}, a unique sensation. These bumps are due to the sun’s action on the air and are called “sun bumps.” It’s owing to these that we novices are not allowed to fly during the day. To experienced airmen they offer no difficulty.

There was a slight accident here this morning. One of the Blériot people (known in our select circle as Blérites) was taxying [running along the ground] in a machine without wings. He got too much speed on, and the machine went head over heels and was utterly wrecked—man unhurt. With the Blériot machine you first have to learn to steer on the ground, as it’s much harder than ours. The men look awful fools going round and round in wee circles....

Very nice lot of fellow pupils here that I am getting to know, one naval man with a whole stock of funny yarns. Nothing to do all day long but sleep. Went into Weybridge this morning and got my suit case. Flora and fauna quite interesting. I live only for the mornings and evenings. More anon. Love to all.

Ever your loving son,

HAROLD.

II.

To his Father.

The Hendon Aerodrome, Hendon.

7th September, 1914.

DEAR DAD,

Only a few lines, as it is already late, and I still have plenty to do. The latest excitement down here is a balloon, especially for our use. It is to be up all night, and we have to take turns in keeping watch from it; four hour shifts, starting to-morrow night. She has 4,000 feet of wire cable, but I don’t suppose we shall be up more than 1,500 feet. It will be frightfully cold work, and in all probability we shall all be sea-sick.

On Saturday night we had a Zeppelin scare from the Admiralty. I was on duty and called out the marines, etc., etc. Ammunition was served round and the machines brought out. Porte [J. C. Porte, Wing Commander, R.N.] went up for a short time.

Tons of love.

Ever your loving son,

HAROLD.

III.

To his Grandmother.

The Hendon Aerodrome, Hendon.

7th September, 1914.

DEAREST GRANNY,

Can only send you a few lines just now as I am so frightfully busy. Thanks so much for your letter received two days back. Am hard at it now from 4.30 a.m. to 11.0 p.m., and one day in five for 24 hours on end. Our latest acquaintance is a captive balloon in which we are to take turns to keep watch in the night. It will be terribly cold work. The watches are 4 hours each, and we shall probably be about 1,500 feet up in the air—the full limit of cable is 4,000 feet. I quite expect we shall all be horribly sea-sick, as the motion is quite different from that in an aeroplane. There is also a rumour that we are going to have an airship down here. We had a Zeppelin scare the other night and had all the marines out, ammunition served round, searchlights manned, and aeroplanes brought out in readiness. It was quite exciting for a false alarm.

It’s pretty chilly work sleeping in tents now. Unless you cover your clothes up over-night, they are sopping wet in the morning. Also there is a plague of crane flies here, which simply swarm all over one’s tent. These are all little troubles, however, which one takes philosophically, and at the same time tries to picture mentally the distress of those at the front. Hope I shall be out there soon; they seem to be having quite good fun.

Must cut short now, so goodbye, Granny dear. Heaps of love.

Ever your loving grandson,

HAROLD.

IV.

To his Father.

The Hendon Aerodrome, Hendon.

11th September, 1914.

DEAR DAD,

Many happy returns. I started writing you last night, so that you might get my letter first thing this morning, but was fated not to finish it.

We had another false alarm and my place was on the ‘phones. I didn’t get off until 12.30 a.m., so gave it up as a bad job and started afresh this morning.

I expect you will have seen in the papers about the accident last night. Lieut. G— went up in the Henri Farman, and on coming down made a bad landing—internal injuries—machine absolutely piled up. Nacelle{2} telescoped and the tail somehow right in front of the nacelle. The accident is expected to have rather a bad effect on the moral of the pupils. Personally it doesn’t affect me; and anyhow I didn’t see G— at all, as I was bound to the ‘phones.

Things are going on much better with me. Yesterday I did five straights [straight flights] alone and managed quite well, having excellent control of the machine, and making good landings, except for the first straights in the morning, when it was rather windy and in consequence the machine was all over the place.

By the way, this is now the third successive night that we have had an alarm. Have not yet been up in the balloon but am looking forward to it. I never thought that we should come down to an old (z 902) gas bag.

Heaps of love and don’t let Mummie get alarmed. You must bear in mind that night flying is ten times more dangerous than day.

Ever your loving son,

HAROLD.

NOTE.

An interesting letter, written in September, is missing. In this the winter described a balloon trip that he made over London in the dark, ultimately coming down near Ashford, and having an exciting experience while landing.

Early in October, 1914, the aviator went from Hendon to the Royal Naval Air Station, Fort Grange, Gosport. A letter of this date is also missing. It described his first cross-country flight, when, owing to engine failure, he had to make three forced landings (from heights of about 4,000 feet), all of which he managed safely without damaging his machine. The engine was afterwards found to be faulty. In this letter he referred to the Commanding Officer’s pleasure that he had made so good a beginning.

2323__perl...