![]()

1 — Army Penetration Operations

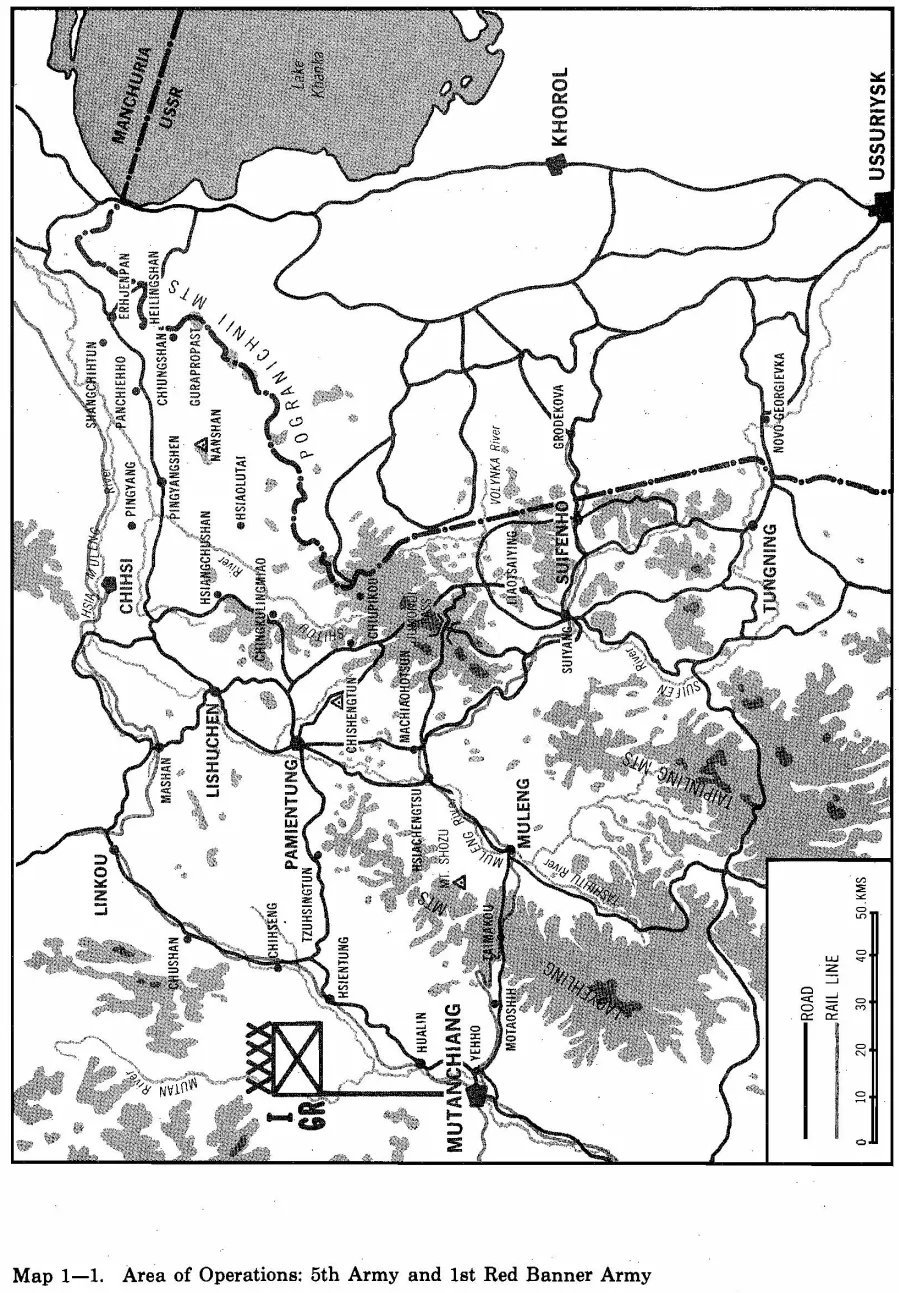

In the Manchurian campaign of 1945, the Soviet Army faced a myriad of offensive tasks. One of the most difficult was that of piercing the imposing Japanese defenses in eastern Manchuria (see map 1-1). Under the best conditions, a penetration operation can be costly, but a Manchurian summer can make the task doubly difficult. Only intensive planning, meticulous preparation, and artful conduct of the offensive can produce positive results. Such was the challenge facing the Soviet 5th Army.

The Route

The most direct avenue of approach from the Soviet Far East into eastern Manchuria was through the eastern Manchurian hills from Harbin in the central valley through Mutanchiang, across the Soviet Far Eastern border at Suifenho, and into the Ussuri River valley north of Vladivostok. The Eastern Manchurian Railroad followed this route, and the Japanese had fortified it with some of the most formidable defensive positions in Manchuria, attesting to the strategic value of this approach. Anchored at Suifenho, these Japanese fortifications dominated the approach into eastern Manchuria in much the same way as the Maginot Line canalized the main approaches to eastern France in 1940 (see map 1-2). On the flanks of this Manchurian fortified zone were dense forests and rugged mountains that the Japanese considered impenetrable by modern mobile armies and difficult even for infantry to traverse. Apparently, few Japanese military thinkers reflected on the French experience in similar terrain adjacent to the Maginot Line in 1940. The Soviets were better students of the Battle of France than the Japanese, and they emulated the German feat of 1940 by traversing the hindering Manchurian terrain and conducting an operational envelopment of Japanese forces in the border zones. Yet, for the Soviets, even this accomplishment was not sufficient. Contemplating deep operations against deep strategic objectives, they could not afford to leave large concentrations of Japanese forces astride communication and supply routes to their rear. So, the Soviets simultaneously conducted shallow tactical envelopment operations against the fortified regions in order to isolate and destroy them with minimum cost.

Missions and Tasks

The Far Eastern Command entrusted the task of penetrating Japanese defenses in eastern Manchuria to Marshal K. A. Meretskov’s 1st Far Eastern Front. A STAVKA directive of 28 June 1945 spelled out the front’s mission{3}. It would strike the main blow with two armies in the direction of Mutanchiang in order to penetrate the border fortified regions and to arrive on a line from Poli through Mutanchiang to Wangching by the fifteenth to eighteenth day of the operation. After consolidating its forces on the west bank of the Mutan River, as well as at Wangching and Yenchi, the front would continue the offensive toward Kirin, Changchun, and Harbin. Separate armies on each flank would support 5th Army’s main attack.

Marshal Meretskov planned to deploy his front in a single echelon of armies. He designated General N. I. Krylov’s 5th Army to make the main attack in coordination with General Beloborodov’s 1st Red Banner Army. The 5th Army would attack in the direction of Mutanchiang, penetrate frontier defenses in a twelve-kilometer sector north of Grodekova, destroy the Japanese Volynsk (Kuanyuehtai) Center of Resistance of the Border Fortified Region, and advance forty kilometers to secure the Taipinling Pass and Suifenho by the fourth day. Meretskov expected 5th Army to advance sixty to eighty kilometers deep and to secure crossings over the Muleng River in the vicinity of Muleng by the eighth day of the operation. By the eighteenth day, the army was to have secured Mutanchiang on the Mutan River, this in conjunction with 1st Red Banner Army advancing on Mutanchiang from the northeast. Once Mutanchiang was secure, Marshal Meretskov planned to have the 10th Mechanized Corps (in the 5th Army’s sector) develop the offensive to Kirin, where it would meet Trans-Baikal Front forces advancing across the Grand Khingan Mountains from the west.{4}

Japanese Defenses

The mission assigned to 5th Army was ambitious and extensive. Success depended on the ability of Krylov’s troops to overcome difficult terrain, strong in-depth fortifications, and a determined, though understrength and unsuspecting, enemy. The Japanese Border Fortified Region extended across a forty-kilometer frontage north and south of the main highway and railroad through Suifenho{5}. Though in most areas the fortified region was ten to fifteen kilometers deep, defenses along the highway stretched thirty to thirty-five kilometers deep. The Border Fortified Region consisted of four centers of resistance, with each center occupying a frontage of from 2.5 to 13 kilometers and a depth of 2.5 to 9 kilometers. The Northeast and Eastern Centers of Resistance (which the Japanese called the Suifenho Fortified Region) covered the approach to Suifenho from the east on a ten- to twelve-kilometer front north and south of the main eastern Manchurian rail line. Twenty kilometers to the north, the Volynsk Center of Resistance (Kuanyuehtai Zone) occupied the wooded, brush-covered hills north and south of the Volynka River. Ten kilometers south of Suifenho, the Southern Center of Resistance (Lumintai) sat on dominant hills overlooking the Soviet Far Eastern Province. These four centers of resistance occupied twenty-five kilometers of the total frontage of forty kilometers. Smaller field works were interspersed between them. A fifth center of resistance, consisting of lighter field trenches, dominated the road junction of Suiyang, thirty kilometers west of Suifenho. Grassy, brush-covered hills surrounded the Border Fortified Region and extended ten kilometers to the rear, finally merging into higher wooded mountains extending to the Muleng River.

The northern flank of the Border Fortified Region blended into the heavily wooded, brush-covered, and presumably impassable eastern Manchurian mountains north of the Volynka River. This lightly defended sector extended sixty kilometers from the northern edge of the Border Fortified Region to the Mishan Fortified Region northwest of Lake Khanka. The southern flank of the fortified region tied in loosely with the northern flank of the Tungning Fortified Region, twenty-five to thirty kilometers south.{6}

Japanese centers of resistance consisted of underground reinforced concrete fortifications, gun emplacements, power stations, and warehouses. Many of the reinforced concrete pillboxes had walls up to one and one-half meters thick, with armor plating or armored gun turrets. Some even came equipped with elevators for transporting the gun and its ammunition. In August 1945 the four main centers of resistance contained 295 concrete pillboxes, 145 earth and timber pillboxes, 58 concrete shelters, 69 armored turrets, 29 observation posts and command posts, and 55 artillery positions. These centers of resistance comprised three to six major strongpoints, each occupying 250,000-square meter sectors, up to two kilometers apart. Strongpoints, usually located on dominant heights, consisted of reinforced concrete positions or several timber and earth bunkers, as well as antitank, machine gun, and artillery firing positions. Machine gun bunkers were positioned every 250 to 350 meters; artillery positions with underground entrances, 500 to 700 meters or less{7}. The centers of resistance usually contained military settlements, complete with warehouses and a water supply. Communications trenches tied the entire complex of strongpoints together. The outer defenses of each strongpoint and the defenses of the center as a whole included multiple barbed wire barriers, mines, antitank ditches, and anti-infantry obstacles, usually covered by interlocking fields of machine gun fire.

Although the Japanese planned for a regiment to defend each center of resistance, a battalion could render credible defense because of the strength of the fortifications{8}. Companies usually defended strongpoints; sections, squads, and platoons manned outposts and satellite bunkers. The Fortified Border Region formed the first important Japanese line of defense in Manchuria.

Field works located eighty kilometers to the rear in the heavily wooded mountains west of the Muleng River composed a second Japanese line of defense. A third line of defense anchored at Mutanchiang, 150-180 kilometers to the rear, completed the defensive zone across which the Japanese hoped to delay and wear down advancing Soviet forces. For the Japanese defensive plan to function correctly, the Border Fortified Region had to take its toll of Soviet strength and time.

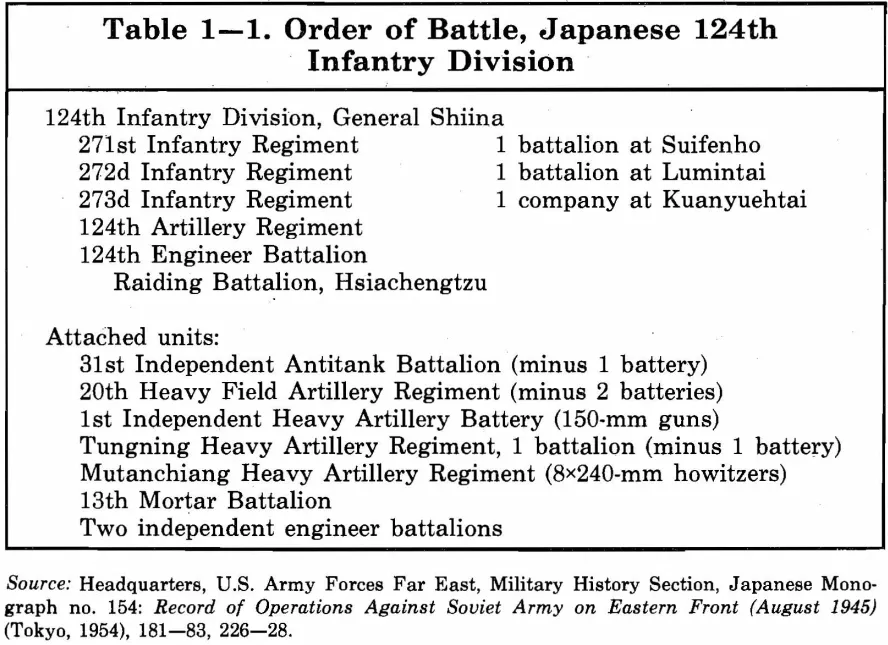

The Japanese 5th Army, which was responsible for the defense of much of eastern Manchuria, positioned its 124th Infantry Division to defend the Suifenho sector (see table 1-1). General Shiina, commander of the 124th Infantry Division, assigned one battalion from each of its three infantry regiments to defend the border region. The 1st Battalion, 273d Regiment, defended the Volynsk (Kuanyuehtai) Center of Resistance, the 1st Battalion, 271st Regiment, defended the Northeast and Eastern Center (Suifenho), and one company of the 1st Battalion, 272d Regiment, held the Southern Center (Lumintai).{9} Additional Japanese security, construction, and reserve units in the border region were available to reinforce the regular border garrison.

The bulk of the 124th Infantry Division was garrisoned at Muleng, Suiyang, and Hsiachengtzu, forty to eighty kilometers west of the border. Some of these units were building fortifications in the mountains west of Muleng in anticipation of a future conflict with the Soviet Union.{10}

The Japanese 126th Infantry Division, with headquarters at Pamientung, defended the 124th Infantry Division’s left, while the 128th Infantry Division, headquartered at Lotzokou, defended its right flank. But both units occupied large sectors, and could thus provide little support to the 124th. Likewise, the 5th Army and First Area Army, with headquarters at Mutanchiang, could provide only minimal reinforcement from army and area army support troops and military school units.

Operational Planning

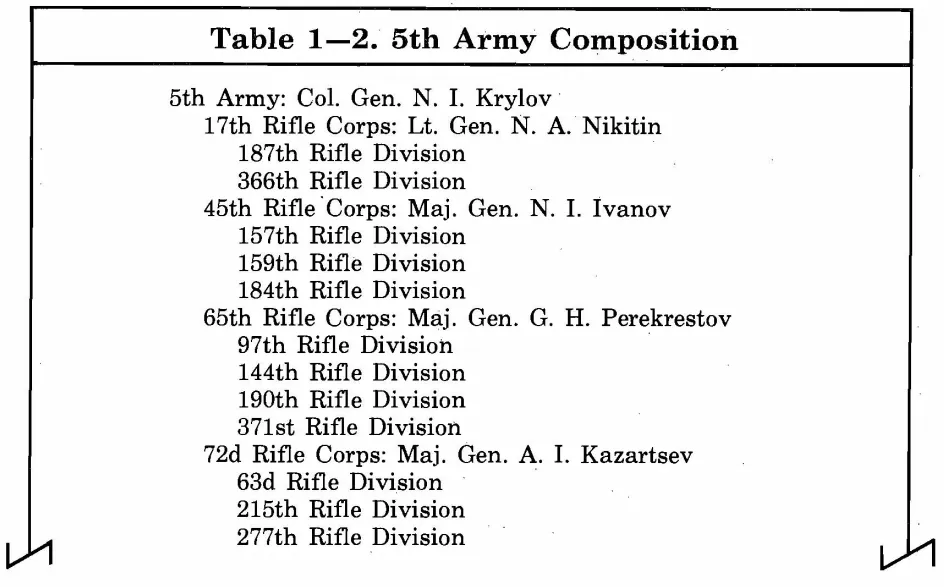

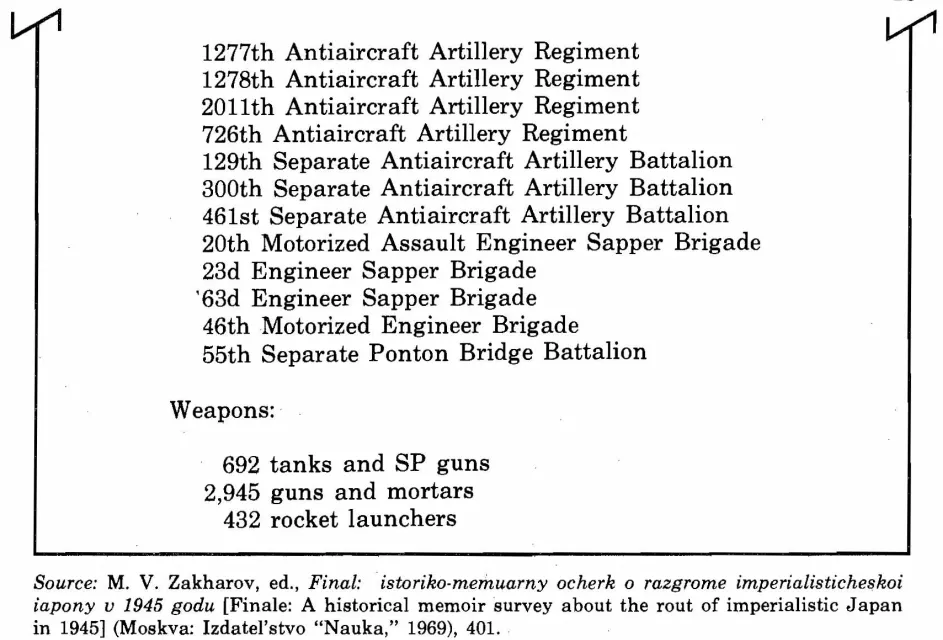

The Soviet 1st Far Eastern Front commander, Marshal Meretskov, structured his forces to insure rapid reduction of this Japanese Fortified Region. Soviet 5th Army was large because Marshal Meretskov provided considerable reinforcement and thus had adequate forces to maneuver through the fortified region and, if need be, to crush the Japanese by sheer weight of numbers and firepower. Soviet 5th Army contained 4 rifle corps of 12 rifle divisions, 1 fortified region, 5 tank brigades, 6 heavy self-propelled artillery regiments, 22 artillery brigades, 4 engineer brigades, an antiaircraft division, and numerous supporting regiments, for a total of 692 tanks and self-propelled guns, 2,945 guns and mortars, and 432 rocket launchers (see table 1-2).{11} Marshal Meretskov tasked 9th Air Army to provide air support for 5th Army; 252d Assault Aviation Division and 250th Fighter Aviation Division were to do likewise for both 5th Army and 1st Red Banner Army during the penetration operation and its pursuit phase; and 34th Bomber Aviation Division and 19th Bomber Aviation Corps were to provide air support as required under air army control.{12} These bomber units would provide invaluable support in the reduction of heavily fortified zones.

By July 1945, 5th Army forces had completed their long movement by rail from the Konigsberg area of East Prussia and had occupied concentration areas in the Ussurysk, Spass-Dalny, and Khorol areas, 100-120 kilometers from the Manchurian border. After about two weeks of reorganization and training, army forces began moving into waiting areas fifteen to twenty kilometers from the border. Because of the difficult, wooded terrain, the waiting areas of the 1st Far Eastern Front were closer to the border than waiting areas of other units assigned to the Far East Command. Movement into waiting areas, conducted primarily at night under stringent control to maintain secrecy, was completed by 25 July. Once in the waiting areas, 5th Army units continued training. The final movement of 5th Army to points of departure adjacent to the border took place during the nights of 1-6 August.{13}

Unit movement was according to the unit training plan, and each unit occupied positions prepared by engineers. Army artillery units, in a single four- to five-hour period, also moved at night into prepared positions. All movement by 5th Army into the sixty-five-kilometer zone along the border was highly screened to maintain secrecy and to achieve surprise. Soviet fortified regions stationed along the ...

![August Storm: The Soviet 1945 Strategic Offensive In Manchuria [Illustrated Edition]](https://img.perlego.com/book-covers/3018076/9781786250421_300_450.webp)