- 596 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

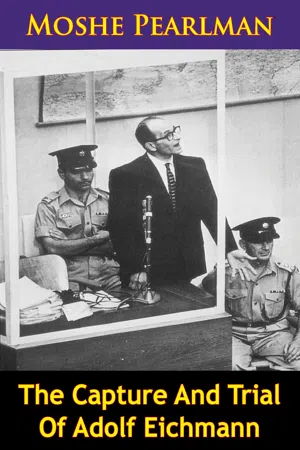

The Capture And Trial Of Adolf Eichmann

About this book

Includes, as an Appendix, a full text of the Indictment, translated from the Hebrew.

The horror trial of the 20th century has been that of Adolf Eichmann, Obersturmbannführer of Germany's death camps—the man who, between 1939-1945, in one way or another, caused the killing of six million men, women, and children.

Out of mountains of courtroom evidence, both live and documentary, Pearlman renders a relevant, reliable account of the drama. The whole story is here: from the capture in Argentina, to the world-famed image of the twitching man in the glass-enclosed dock as he listened to the sagas of the ghetto fighters, the confrontation of the accused and witnesses who came back as if from the dead, the indictment enunciated by Hausner, and the defense arguments of Servatius. And lastly the words of Eichmann himself: "I received orders and I executed orders."

A gripping read.

The horror trial of the 20th century has been that of Adolf Eichmann, Obersturmbannführer of Germany's death camps—the man who, between 1939-1945, in one way or another, caused the killing of six million men, women, and children.

Out of mountains of courtroom evidence, both live and documentary, Pearlman renders a relevant, reliable account of the drama. The whole story is here: from the capture in Argentina, to the world-famed image of the twitching man in the glass-enclosed dock as he listened to the sagas of the ghetto fighters, the confrontation of the accused and witnesses who came back as if from the dead, the indictment enunciated by Hausner, and the defense arguments of Servatius. And lastly the words of Eichmann himself: "I received orders and I executed orders."

A gripping read.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access The Capture And Trial Of Adolf Eichmann by Moshe Pearlman in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & Holocaust History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1—PRELUDE TO CAPTURE

THE FIRST DAY OF SPRING WAS A fateful day in the life of Adolf Eichmann. On that day, in 1935, he got married. On that day, in 1960, the seal was put on the plan for his capture.

On March 21, 1960, Eichmann rose early, as usual, pottered about the small, stark, mud-colored brick house in the dreary San Fernando suburb of Buenos Aires where he lived with his wife and three of his four sons, shaved carefully, washed in a primitive bathroom which lacked running water, dressed and sat down to a German-style breakfast. At 6:45 he left the house, on whose door was a card bearing the name “Klement.” It was now as Señor Klement that he walked the two hundred yards to the nearest bus stop to wait for one of the three buses he would be taking to reach his place of work, the Mercedes-Benz factory in Suárez, at the other, southeastern, end of the city. When he reached the factory, he clocked in with a card made out in the name of Ricardo Klement.

As he left the house, his face and every movement were watched through powerful binoculars by a young man half his age whom we shall call Gad.

Gad was seated behind the drawn blind of a window in a house situated four hundred yards from, and offering an uninterrupted view of, the house marked Klement. Two small holes in the blind, looking like moth holes from the outside, gave vision for the lenses of binoculars. He watched the house, as he had watched it now every morning for several weeks, saw Señor Klement open the door, turn to say good-bye to someone inside, close the door, and then walk down the dirt path to the edge of the cottage grounds, ringed by a chicken-wire fence. Gad followed him with his eyes as he walked toward the bus stop and stayed with him until the bus pulled up. He left his seat at the window only when the bus was out of sight. He then went to the telephone to make a two-word call. “Yigal?” he queried; and then, when he received the affirmation, he added, “Karagil.” The word is Hebrew for “as usual.” He hung up and went to make himself some coffee.

Yigal, at the other end, after hearing from Gad, put through his own call to Dov. “Beseder,” he said—“Okay.”

Dov had a room not far from the Mercedes-Benz works. For what he had to do now, there was plenty of time. He waited thirty minutes and then, taking a special briefcase which did not look special, he casually sauntered over to the bus stop nearest the factory. He got there at 7:20. A few minutes later, a bus hove into sight. As it approached he scrutinized its destination sign, giving a slight show of disappointment for the benefit of the three persons waiting with him, to suggest that this was not his bus. The four waited as the passengers began to alight. Dov watched them all, apparently idly, as people in a waiting queue usually do. He seemed, if anything, more listless than the others—since he would have to wait for the next bus. He stood with slightly sagging shoulders, his briefcase now in front of him resting on his body, its base supported by both hands, as if, with the long wait, he was reluctant to overburden one arm. The passengers got off, Señor Klement among them. Dov watched him. And the concealed tip of the middle finger of his right hand pressed sharply against the back of the briefcase near the bottom. As the bus pulled away, carrying the three who had waited with him, Dov continued watching Señor Klement as he walked across the road to the factory gate. Dov turned slowly so that the front of his briefcase always faced the figure of Klement. The finger on his right hand kept repeating its pressure. No one observing him could have seen the camera lens behind the small aperture of the lock on the briefcase. As Klement disappeared inside the plant, Dov lingered a few minutes at the bus stop. No one had joined him and no one appeared to be watching him. So he left and walked back to his room, telephoning Yigal that “Hakol Beseder”—”All’s well.” Had there been anyone about, he would have caught the next bus as a bona fide commuter, and telephoned later to Yigal that Señor Klement had gone to work as usual.

Yigal, Gad and Dov were Israelis. All three were in their late twenties. Yigal, taller than his companions, was dark, his hair black, his brown eyes set in a long, pale face that belied an outdoor youth spent in the desert. He was the leader of the trio. The expression on his face suggested the grave young executive, heavily conscious of his responsibilities. In fact, he carried responsibilities easily, was a deft planner, and exercised command with a light touch. Gad and Dov were both of medium height, blond, and of cheery countenance; they moved through life as if they had not a care in the world. Gad was broad-shouldered, and his bronzed round face was topped by thick woolly hair. Dov, of slim build, had a mop of corn-colored spikes, which gave his healthy suntanned face a perpetually boyish air.

All three had spent many years as youthful pioneers creating a cooperative farm village in a desert outpost in southern Israel. Now they were together again, in Buenos Aires. They had come to kidnap Adolf Eichmann.

They were almost certain that the man they had kept under continual surveillance for several weeks, and who went under the name of Ricardo Klement, was Eichmann. But their certainty had to be absolute before they could proceed with the capture plan. He was living as the second husband of a lady who was known beyond doubt to have been the wife of Adolf Eichmann. Three of the four sons of the family were known beyond doubt to be the sons of Adolf Eichmann. What was not clear beyond doubt was whether Ricardo was Eichmann or whether he was indeed what he and Señora Klement claimed him to be, her second husband, whom she had married after the death of her first.

The reason for the uncertainty was that, while much was known of the activities of Eichmann during the heyday of Nazi rule, very little was known of the man himself. For he had taken good care to remain in the shadow while engaged in his grim Gestapo business. He rarely had appeared in front of the cameras. And details of his person were recorded only in the secret documents in his personal file at Nazi SS headquarters.

These particulars were in the file which Yigal had brought with him from Israel. And so he knew Eichmann’s height, the color of his eyes, the color of his hair, the size of his collar, the size of his shoes, the dates of his promotions, the date of his marriage and the birth dates of his sons. He also had a photograph which had been taken in the late thirties and which had been found in 1946. But many years had now passed. He might today have no hair. His face would have undergone changes in more than twenty years, even if he had not resorted to plastic surgery—a possibility which could not be ruled out. His height would have remained the same, and this tallied with the height of Klement. So did the color of his eyes. The size of his neck and feet could be checked only with physical custody; they could not help to identify him from a distance.

The three Israelis had managed to photograph “Klement” numerous times since they had started their surveillance. A casual encounter, with a concealed camera, while he walked to the bus that took him to work; camera shots as he descended from the bus near his factory. They could not be perfect portraits. For they had to be taken surreptitiously, with no time to linger, no time to focus. It was important to snap him. It was even more important to give him not the slightest ground for suspecting that he was being watched or followed. The results, at times, were odd. Yigal today has some fine shots of Señor Klement’s shoes and the cuffs of his trousers. He also has some excellent enlargements of a waist-coated belly.

But they also managed to get shots of his face. There was a good likeness to the old photograph they had of Eichmann. And there seemed to be no signs of plastic surgery. But Señor Klement was a much older man. And they could not decide with complete certainty that the subjects of the two sets of photographs were the same. Nor could they tell definitely whether the likeness was real or whether it reflected wishful thinking. They needed something more concrete to convince them that Klement was Eichmann living under an assumed name.

This Monday, March 21, passed as every weekday had passed since the three Israelis had begun their vigil. Klement had been seen to leave the factory at 12:30 P.M. and to enter a nearby restaurant, where he had ordered the same meager lunch he ordered every day. At 1:30 he had left the restaurant and strolled away from the factory for some three blocks, and by 2 P.M. he was back at work. At 5:30 P.M. he had left. But today, instead of walking straight to the bus stop, he stepped into a nearby horticultural nursery and emerged carrying a cellophane-wrapped bunch of flowers. He then caught his bus.

Dov added this fact to the usual telephone report he made to Yigal as soon as the bus had moved off. Yigal was careful to avoid mentioning it when he telephoned Gad that Klement had left work.

Three quarters of an hour later, Gad telephoned Yigal. The man, he said in Hebrew, had reached home, but he was carrying a bouquet. Yigal’s response was the code word for a meeting. He set it for 9:30 that night. He called Dov to give him the same order. Such meetings were held in a room they had rented in a Buenos Aires suburb far from both the Klement residence and the Mercedes-Benz factory.

Yigal was already there when Gad and then Dov arrived. His eyes showed excitement, but the rest of his expression was as grave as usual. His first question to both was, “What do you make of the flowers?” They thought for a few minutes and then Yigal added, “What is today’s date?”

“The twenty-first of March.”

“What happened to him on the twenty-first of March?”

Seconds went by before both exploded at the same moment. “He got married!”

“Precisely,” said Yigal. “So today is his wedding anniversary. The twenty-fifth, in fact. Does anything strike you as odd?”

“Heavens, of course,” Gad exclaimed. “What would the second husband of Mrs. Eichmann be doing remembering her first wedding anniversary? And why, if he did, would he wish to commemorate that event with flowers?”

Dov grinned. “So Klement is Eichmann after all. There can be no doubt now. This is the break we’ve been waiting for.”

“Boys,” said Yigal, “this calls for two immediate acts. A drink, and a cable home. The drink we’ll have right away. The signal I’ll send on my way back.”

Forty minutes later, the following cable was sent to an address in Israel from a post office midway between the meeting place and Yigal’s apartment: “Ha’ish hu ha’ish.” The nearest English translation is “The man is the man.”

Who was this man Adolf Eichmann?

The first whisper of his name in public came dramatically from the witness box at the International Military Tribunal in Nuremberg at the end of 1945. Overnight it became a symbol of horror. And as the trial proceeded, defendants, witnesses and counsel unfolded a tale of slaughter unprecedented in its magnitude and cruelty—the slaughter of six million Jews. The man responsible for the organization of this mass murder, they said, was Adolf Eichmann.

In the dock were men whose names were familiar to the world, neon stars of the dark sky that was Nazi Germany. Göring and Keitel, Ribbentrop and Seyss-Inquart, Kaltenbrunner and Frank, Frick and Streicher, Sauckel and Jodl and others. For twelve years they, as principal ministers of the Führer, had ruled Germany, and for five of those years more than half of Europe. In that brief period, they had loosed upon the universe more misery than had any regime in history. They had launched a world war in which millions of soldiers and civilians had been killed in military operations. But this was only one of the reasons why these men were now in the dock facing charges as war criminals before a tribunal comprising judges from America, Russia, Britain and France. The basic charge against them was the crime against humanity.

In war, soldiers meet death. Civilians too are often casualties when caught in the cross fire of opposing units. But these men were now charged with the deliberate killing of wholly innocent people—men, women and children—for no other reason than that they belonged to a national, religious or ethnic group whom the Nazis despised. This was the crime against humanity.

And this is what made the men in the Nuremberg dock feel so uncomfortable. It was natural that men like Göring and Kaltenbrunner should look deflated, brought low by disaster, their egos shattered by the fall from dizzy heights of power to a humble place before the bar of justice, facing the judicial representatives of peoples against whom their might had been flung—and broken. But before appearing for trial, they were reported to have retained a certain cockiness, as if they were recalling the peaks they had reached before the collapse, the piles of winning chips the gamblers had amassed before their luck had turned. They had lost all. But they had come near to gaining all. They had been unfortunate. But misfortune was not a crime. They had a fleeting hope that they might yet cheat the gallows.

But then they were brought into court. And in court they heard the stories, told quietly, dispassionately, factually, by prosecuting counsel, backed by documents, records and living witnesses. They were stories of murder. And as the grim record was unrolled, the men in the dock began to lose whatever jauntiness they had mustered. As the eyes of the court and public and representatives of the world press turned to watch them, their own eyes dropped, their shoulders sagged, and they fidgeted in embarrassment. It was one thing to be a glamorous warrior in an army that had fought and lost. It was quite another to be a common criminal, part of a sordid gang whose power had enabled them to undertake, on a mighty scale and in more than sixteen countries, every crime known to man, and some not known until they had conceived them.

These crimes included “murder, extermination, enslavement, deportation, and other inhumane acts committed against civilian populations before and during the war, and persecutions on political, racial or religious grounds.”

The Nuremberg court itemized some of the methods used. “The murders and ill treatment were carried out by divers means, including shooting, hanging, gassing, starvation, gross overcrowding, systematic undernutrition, systematic imposition of labor tasks beyond the strength of those ordered to carry them out, inadequate provision of surgical and medical services, kickings, beatings, brutality and torture of all kinds, including the use of hot irons and pulling out of fingernails and the performance of experiments, by means of operations and otherwise, on living human subjects....”

The men in the dock listened. Some had the grace to look shamefaced.

The inexorable list continued. “They conducted deliberate and systematic genocide, viz., the extermination of racial and national groups...particularly Jews, Poles, and ...

Table of contents

- Title page

- TABLE OF CONTENTS

- 1-PRELUDE TO CAPTURE

- 2-THE CHASE BEGINS

- 3-ON THE RUN

- 4-THE CHASE RESUMED

- 5-THE CAPTURE

- 6-THE DIPLOMATIC BATTLE

- 7-THE COURTROOM

- 8-THE PRELIMINARY ARGUMENTS

- 9-THE CRIME

- 10-THE ACCUSED

- 11-THE INTERROGATION

- 12-THE EVIDENCE

- 13-ON THE STAND

- 14-THE CROSS-EXAMINATION

- 15-QUESTIONS FROM THE BENCH

- 16-THE JUDGMENT

- APPENDIX-FULL TEXT OF THE INDICTMENT