- 175 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

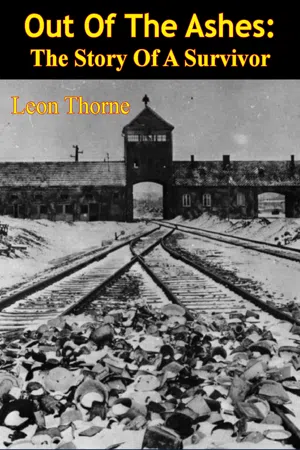

Out Of The Ashes: The Story Of A Survivor

About this book

You are holding in your hand one of the most remarkable and unforgettable personal narratives to emerge from the Hitler holocaust in Europe.

While there have been literally thousands of books written about and by the life of the Jews during the years when six million Jews were wiped out in concentration and extermination camps, few volumes are as authentic and as stark as Out of the Ashes; Rabbi Thorne not only possesses total recall; he owns a literary style which brings to life a period which shall forever be remembered as one of the most dramatic eras in human existence. But this is more than a personal document. It represents the agony of an entire people and even the reader who thinks he knows what happened under Hitler will gasp in amazement at this story of a man who, deeply religious and faithful to the precepts of Orthodox Judaism, manages to retell the tale of a handful of years which saw men, women and children subjected to atrocities beyond human imagination.

You will read in this book of moments of heroism, self-sacrifice and destruction which you will always remember. You will be convinced that this is exactly how it was and you will marvel at how the author managed to survive scores of "Actions" and pogroms. You will wonder how he survived. But at the same time, you will understand how, in surviving, Rabbi Thorne held fast to his belief in the ultimate triumph of the Jewish people.

Although Out of the Ashes is full of sadness, it is also replete with stories of the victory of the human spirit. It is a valuable historical document; it is, for sheer story-telling, unsurpassed by any other writer who lived through these years. It is the story of one man, of an entire people and of a history which all mankind would do well to ponder.

Out of the Ashes is a major book, a great contribution to the literature of our time.— Print Ed.

While there have been literally thousands of books written about and by the life of the Jews during the years when six million Jews were wiped out in concentration and extermination camps, few volumes are as authentic and as stark as Out of the Ashes; Rabbi Thorne not only possesses total recall; he owns a literary style which brings to life a period which shall forever be remembered as one of the most dramatic eras in human existence. But this is more than a personal document. It represents the agony of an entire people and even the reader who thinks he knows what happened under Hitler will gasp in amazement at this story of a man who, deeply religious and faithful to the precepts of Orthodox Judaism, manages to retell the tale of a handful of years which saw men, women and children subjected to atrocities beyond human imagination.

You will read in this book of moments of heroism, self-sacrifice and destruction which you will always remember. You will be convinced that this is exactly how it was and you will marvel at how the author managed to survive scores of "Actions" and pogroms. You will wonder how he survived. But at the same time, you will understand how, in surviving, Rabbi Thorne held fast to his belief in the ultimate triumph of the Jewish people.

Although Out of the Ashes is full of sadness, it is also replete with stories of the victory of the human spirit. It is a valuable historical document; it is, for sheer story-telling, unsurpassed by any other writer who lived through these years. It is the story of one man, of an entire people and of a history which all mankind would do well to ponder.

Out of the Ashes is a major book, a great contribution to the literature of our time.— Print Ed.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Out Of The Ashes: The Story Of A Survivor by Leon Thorne in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & Holocaust History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

THE STORM

That trouble was brewing was evident from the rumors we heard and the new orders that had been issued. Late in July, 1942, the District Prefect at Sambor had demanded that there be an increase in the Jewish Ordnungsdienst from 40 to 100 men. Of itself, this edict could have been useful to us. It meant that an additional 60 young folks would be able to work at light jobs instead of heavy tasks. Yet we all realized that the Prefect did not have our benefit in mind. Then there followed a second order. All villages in the area were to be “cleared” of Jews within three days! It was suddenly recalled that six months earlier the Prefect had ordered the members of the Jewish Council to appear before him and had told them that when the time came for transporting the Jews elsewhere, the job would have to be done, in large measure, through the Jews themselves—through the Council. And if any of the German orders were not heeded, the members of the Council as well as the Ordnungsdienst would be hanged in the center of the town.

The day the new order was issued, the Jewish Council hurriedly called together its staff to make up a list of all the Jews living in the surrounding villages, of which there were almost 100. The only Jews exempted were those working for the Germans.

In the Evidenzbüro of the Jewish Council there were accurate lists of Jews living both in the town and in the villages, whereas in the office of the German Registrar the Jews had not been listed at all, for the files had been destroyed early in the occupation.

The Council members worked through the first night and on the morning of the second day the lists were ready. More than 2,000 names were included. The Council hired 100 carts owned by local farmers and sent the entire Ordnungsdienst to each of the villages, with a list of every Jew in that village.

Two days passed. In the afternoon hours of the third day, just a few hours before the three-day deadline came, the carts slowly entered the town from the various villages in the outlying districts. Jews, with their wives, children and meager possessions, had come in the carts.

It was a Friday, toward evening. The rain was falling steadily, drearily, as though the Heavens were lamenting the bitter fate of the village Jews. On the carts, together with the Jews, were mountains of bedding, without sheets; pots and pans, pails and shovels. And among these items were huddled little children, looking out at the world with intelligent but curious eyes. Aged Jewesses wearing kerchiefs, and white-haired and bearded Jews, who had not left their villages for decades, were looking at us with frightened eyes. They seemed to ask us with their eyes why they had been torn away from their homes, the houses in which they have lived for so long. Why had they been driven out in the rain, and where were they being taken?

As I sit now in my hiding place, in the hole under the stable, writing down what happened on that sorry day, I realize that this Friday remains in my mind as one of the blackest, most miserable moments in my life. The unspeakable distress, the helplessness of these people—and our own impotence—come back to me with a rush of emotion.

The Jews of Sambor were terribly moved by what they had seen and, in an act of solidarity, they were about to take the Jewish families into their own homes—but they were reminded that at the last moment the German authorities had ordered all the incoming Jews to be placed in military barracks to be guarded by Ukrainian militiamen. The town Jews were not permitted to enter the building, with the exception of a few who worked in the soup-kitchen.

The Ordnungsdienst, threatened with the gallows or, at best, the Janover extermination camp, took great pains to carry out whatever orders were issued them. They were to have transported the unfortunate Jews to the town, but they found that the Ukrainians—among whom the village Jews had lived—were eager to drive them out. The Jews, reluctant to carry out their unhappy tasks, discovered that the Ukrainians had already done the job quite well enough.

The human tragedies involved in the mass moving of population were horrible to see. One case remains vivid in my mind. You will recall that Jews who were employed by Germans did not move out of their villages. This, however, was not always a “break” for the men and women concerned. There was a Jewish couple with an infant child and both mother and father worked for the Germans, and as a result, were forced to remain with their employers. Their child, on the other hand, possessed no certificate of occupation and, according to orders, had to leave the village. The mother, hysterical with fear and anger, could not leave with her child, for when any Jew left his place of work, the punishment was death.

The child was taken away from her, but that very night, the mother fled from her village and came to Sambor. With great effort, she was smuggled into the barracks and reunited with her infant. The tension, however, made the mother temporarily demented and the Ukrainian guard reported her abnormal behavior to the German police. That evening, the Germans led the mother out of the barracks and attempted to pry the child out of her arms. Her violent opposition to the cruel Nazis was so great that they were literally unable to get the child away from her. So they drove the frenzied woman, still clutching her youngster, to the Jewish cemetery.

There, two shots united the mother and child forever

Day by day, the situation of the Jews in the barracks grew worse. Life became more difficult, and the uncertainty of their fate made the Jews depressed and lethargic.

And then the rumors started up again. On Sunday, August 2, 1942, all was quiet, but on Monday, a wild story began to make the rounds. No one knew who had brought the story to Sambor, but everyone was talking about it. On Tuesday, the very next day—it was said—all the Jews were to be slaughtered!

In panic, Jews ran to the headquarters of the Jewish Council in order to learn the truth. But the Council officers refused to talk. Instead, they merely stood in front of the building, looking grave. Before any questions could be put to them, they gesticulated that they knew nothing, but the expression on their faces indicated otherwise. We learned that there were 50 boxcars standing on a siding in the railway station, which were to be used to transport the Sambor Jews to another area to be shot—or at least this is what the Aryan railway workers had told the Jews who had been assigned to the station.

Meanwhile, the hour of the street curfew was approaching, and all Jews had to hurry home. There, they remained in terror, waiting helplessly for word from Council officials. Although the Jews wore their heavy winter coats, they trembled. What were they to do? Should they remain out-of-doors to avoid the Nazis and thereby gamble that they would not be caught? Or would they be better off to remain at home during the cold night, on the chance that nothing would be attempted until morning?

It was a terrifying period.

We, at that time, were living on the outskirts of town, and I was tense with anxiety, for inactivity in the face of imminent peril is difficult to face. Other Jews were no less upset. At the Council headquarters, the corridors and the offices were crowded with Jews who had hurried there to hide, in spite of the curfew. Council officials themselves were bringing their own wives and children to the building, to hide them in the attic and in the cellar. All signs pointed to a calculated wholesale slaughter of Jews.

Slowly, information began to seep down to all the Jews, and they began to learn what had happened on Monday. At about noon, Dr. Schneidscher, the president of the Council, and his Deputy, Dr. Zausner, as well as other officers of the Council, had been ordered to appear at Police Headquarters. There they found local police officers and Gestapo members, who told them that action was to be taken against 1,000 Sambor Jews. There would be no executions in town. Instead, the Sambor Jews, plus 2,000 Jews from the villages, would be sent to an area already agreed upon by the German authorities. The Council would play no part in assisting the Germans, but the Jewish leaders were being kept informed of developments in order that there should be no breakdown in plans. The Council would be required to list all “criminals,” “thieves” and “beggars” to facilitate matters for the Germans. As usual, the Council was threatened with collective hanging if they refused to co-operate with the Nazis.

The Council leaders pleaded for a few hours’ time for consultation and planning. The Police accepted the plea and agreed to wait, demanding brandy to help them pass the hours more pleasantly. The Jews of the Council were faced with a difficult dilemma: they were to become murderers or martyrs, and the choice, in either case, was a cruel one.

Time moved with agonizing slowness. Periodically, the phone would ring and the sadistic Gestapo would ask what decision had been taken. Some of the Jewish officials, unable to take a stand, went into hiding themselves so that they would not have to cast a vote.

Eventually, however, the moment of truth had to come. Rationalizing that they could perhaps save other Jews, the Council leaders agreed to compile lists which, they knew, would send fellow Jews to certain death.

No one seriously believed that the Nazis would limit themselves to the names on the lists; it was clear that the lists would indicate the houses in which Jews were living. At that time, Jews were dispersed throughout the area and had not yet been driven into a definite ghetto quarter. It seemed that in yielding to the Germans, the Council spokesmen were attempting to save their own lives and those of their families. It was thought by some that the Council leaders had received pledges that the Germans would have found the Jews no matter what they had decided to do. Thus, the Council leaders could dig for excuses to explain their capitulation.

When I learned what the final decision was, I ran back to my home on Kosharova Street, where my family waited in terror to learn what developments had taken place. Would I bring good news? Or would I be the bearer of evil tidings? I had to tell them the truth, bitter though it was. And I still remember how my youngest brother cried out in anger and desperation, “The damned criminals! Where can I get a gun? Any gun? I’d walk to my death with joy if I could take some of those men along with me! The dogs!”

Something had to be done. We could not simply wait in our room for fate to overtake us. There was no sense in thinking of fighting back. We had no weapons. My wife ran upstairs to our Polish landlady, to ask for permission to hide in her cellar. She was a decent woman of Italian origin and allowed us to use her cellar but warned us that the Ukrainians who lived in the same house must not discover us. Silently, on tiptoe, my family—consisting of more than twenty persons—began to steal down to the cellar. I decided to remain upstairs so that, if necessary, I could run to the Jewish Council if I were needed.

To my dismay and shock, I noticed—when everyone was already in the cellar—that my Ukrainian neighbor had been watching the entire operation. As I walked toward him, he smiled and asked me, “Why are you all creeping into the cellar so late at night?” From the tone of his voice, I realized that he completely understood our desperate situation. I knew Ukrainians too well to allow myself to be deceived, even for an instant, as to their generosity and charity. So I spoke up and said, “You know what is happening. I need help. And I’m willing to pay you for it. If you remain quiet, and tell nobody what you have seen here tonight, I’ll pay you well.” And then I told him, “I’ll give you, right away, two new suits, an overcoat and a gold ring.”

He quickly agreed to my terms and promised to do all he could to help me. I trusted him at the time and after I paid him off, we parted on the best of terms. I hurried through the fields back to the headquarters of the Council.

Excitement still reigned at headquarters, for people kept pouring in, regardless of the curfew law. Even the sight of a few dead Jews, shot because they had been caught defying the curfew, had not stopped the majority from coming to the Council. The leaders of the Council stood by, quietly, guilt written on their faces. The entire Council office was nightmarish in its total effect. A detachment of Jewish militiamen was present, waiting for the awful moment when it would have to help the Germans catch and shoot fellow Jews. On another floor, a handful of officials were compiling lists of Jews to be taken away and murdered. There were 7,000 Jews in the town and 1,000 “criminals” had to be found. Of course, there were no “criminals” among them, and the very Jews crowding into the office would be on the list, innocent Jews, oblivious, at the moment, to their fate at the hands of those compiling the lists.

Then, at about three o’clock in the morning, a sound of trucks was heard in the yard. Everyone became panic-stricken and both town Jews, village Jews and officials tore about senselessly yelling to each other, and to themselves, “Hide! Hide! Quick! Quick!” And then the agonizing cry: “The Gestapo are coming!”

It was true. A long row of military vehicles drove up to the Council building, and in the cars were German police of all variations, well equipped with pistols, rifles and other military gear. Rapidly, the officer in charge jumped from his car, ran into the headquarters and reappeared with the dreaded lists in his hand and distributed them to his men.

In the streets there was a deathly silence.

And in each little Jewish home, the pious, observant Jews still slept, some of them unaware of the horror that was to come upon them.

These Jews had committed but one crime: they believed in one God, the Creator of the world, whose Laws they were to obey at all times. As the morning came, these Jews rose from their beds, said their prayers, as Jews had been reciting them for centuries, and awaited the new day. They did not know how that day was to end. Perhaps they should have been grateful for that innocence.

As I try to put down on paper what occurred, I wonder if there were greater horrors. Did the world’s breath stop? Apparently not. But I find it hard even to recreate a portion of those hours.

When morning came, the whole town was surrounded by the police, who held their guns ready for murder. Every street corner was covered; there was no escape.

And the police were thorough. Men, women and children were driven from their homes and hiding places. Many had been torn from their beds, wearing only night clothes and stumbling about bare-footed. Mothers, shocked and disheveled, carried their helpless, innocent children in their arms—and these “criminals” were hunted down with rifle butts and rubber truncheons and driven to areas where other police rounded them up in groups of forty and fifty. There was no charity shown. It was a bitter, cruel and poisonous exhibition of the bestiality of man.

When Dr. Schneidscher, the head of the Jewish Council, saw, from his window, that the “action” was not going “according to plan,” he broke down and ran wildly into the bloody street to argue with the Germans. He did not get very far. He was slugged with a rubber truncheon and collapsed in the gutter. Other Council members carried him back into the building, unconscious. Dr. Zausner, too, was badly beaten by the police, who complained that the Council had warned the Jews that they were coming and, as a result, they had captured only a few hundred victims.

Slowly, the Jewish militiamen returned to the Council, beaten and blood-spattered, exhausted and angry. They had helped the Germans in an ugly job and yet the Germans had mishandled them, too, for the Nazis felt the Jews had not uncovered enough of the hiding places of their fellow Jews.

Similar “actions” took place in other towns as well at the same time. The Gestapo went into action in...

Table of contents

- Title page

- TABLE OF CONTENTS

- DEDICATION

- AUTHOR’S PREFACE

- FROM THE CELLAR

- SCHODNICA

- SAMBOR

- BOOKS IN SAMBOR

- THE STORM

- JANOVER CAMP

- ADVENTURES OF BATHING

- HOPE?

- PIOUS PRISONERS

- THE PERSECUTIONS CONTINUE

- ESCAPE INTO THE LEMBERG GHETTO

- IN THE LEMBERG GHETTO

- DROHOBYCZ

- DESPAIR IN THE JEWISH QUARTER

- MY START IN DROHOBYCZ

- THE SITUATION OF THE CHRISTIANS

- IN THE SHADOW OF DEATH

- THE EXECUTION

- INTERVAL

- THE LAST DAYS OF THE SAMBOR GHETTO

- THE LAST DAYS OF THE DROHOBYCZ GHETTO

- THE CAMP

- HYRAWKA

- THE LIQUIDATION OF THE “W” CAMPS

- WHY THERE WAS NO RESISTANCE

- NAFTALI BACKENROTH

- BESKIDEN, CELLAR AND LIBERATION