- 124 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Fix Bayonets!

About this book

A collection of picturesque and observant stories about the hard-fighting Fifth Marine Regiment in France by a writer who has been called the Kipling of the Marines Corps.

During his 27 years as a Marine officer, John W. Thomason also became one of America s foremost illustrators and by virtue of his singular combination of talents, Thomason immortalized the Marines who served in World War I.

These stories follow their grim daily lives with ironic humor, acute observation and sympathy from Belleau Wood to the march to the Rhine.— Print Ed.

During his 27 years as a Marine officer, John W. Thomason also became one of America s foremost illustrators and by virtue of his singular combination of talents, Thomason immortalized the Marines who served in World War I.

These stories follow their grim daily lives with ironic humor, acute observation and sympathy from Belleau Wood to the march to the Rhine.— Print Ed.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

III—MARINES AT BLANC MONT

“The taking of Blanc Mont is the greatest single achievement of the 1918 campaign—the Battle of Liberation.”—MARSHAL PÉTAIN.

THE battalion groped its way through the wet darkness to a wood of scrubby pines, and lay down in the slow autumn rain. North and east the guns made a wall of sound; flashes from hidden batteries and flares sent up from nervous front-line trenches lighted the low clouds; occasional shells from the Boche heavies whined overhead, searching the transport lines to the rear. It lacked an hour yet until dawn, and the companies disposed themselves in the mud and slept. They had learned to get all the sleep they could before battle.

A few days before, this battalion, the first of the 5th Regiment of Marines, a unit of the 2d Division, had pulled out of a pleasant town below Toul, in the area where the division rested after the Saint-Mihiel drive, and had come north a day and a night by train, to Chalons-sur-Marne. Thence, by night marches, the division had gathered in certain bleak and war-worn areas behind the Champagne front, and here general orders announced that the 2d was detached from the American forces and lent by the Generalissimo as a special reserve to Gouraud’s 4th French Army.

Forthwith arose gossip about General Gouraud, the one-armed and able defender of Rheims, who had broken the German offensive in July. “A big bird with a beak of a nose and one of these here square beards on ‘im—holds hisself straighter than the run of Frog generals,” confided a motorcycle driver from division headquarters. “Seen him in Challawns. They say he fights.”

“Yeh, ole Foch has picked the right babies this time,” observed the files complacently. “Special reserve—that’s us all over, Mable! Hope they keep us in reserve—but we know they won’t! The Frogs have got something nasty they want us to get outa the way for them. An’ we see Chasser d’Alpinos and Colonials around here. Somethin’ distressin’ is just bound to happen.”

“Roll your packs, you birds! The lootenant passed the word we’re goin’ up in camions to-night!”

The battalion got aboard in its turn, just as dusk deepened into dark, rode until the camion train stopped, and marched through the rain to its appointed place.

I

The dawn came very reluctantly through the clouds, bringing no sun with it, although the drizzle stopped. The battalion rose from its soggy blankets, kneading stiffened muscles to restore circulation, and gathered in disconsolate shivering groups around the galleys. These had come up in the night, and from them, standing under the dripping pines, came a promising smell of hot coffee. Something hot was the main consideration in life just now. But the fires were feeble, and something hot was long in coming. The cooks swore because dry wood couldn’t be found, and wet wood couldn’t be risked, because it would draw shell-fire. The men swore at the weather and the slowness of the kitchen force, and the war in general, and they all growled together.

“Quite right—entirely fitting and proper!” said the second-in-command of the 49th Company, coming up to where his captain gloomed beside the galley. “We wouldn’t know what to do with Marines who didn’t growl. But, El Capitan, if you’ll go over to that ditch yonder, you’ll find some Frog artillerymen with a lovely cooking-fire. They gave me hot coffee with much rum in it. A great people, the Frogs—” But the captain was already gone, and the second-in-command, who was a lean first lieutenant in a mouse-colored raincoat, had to run to catch up with him.

They returned in time to see their company and the other companies of the battalion lining up for chow. This matter being disposed of, the men cast incurious eyes about them.

The French artillerymen called the place “the Wood of the Seven Pigeons.” There were no pigeons here now. Only hidden batteries of 105s, with their blue-clad attendants huddled in shelters around them. The wood was a sparse growth of scrubby pines that persisted somehow on the long slope of one of the low hills of Suippes, in the sinister Champagne country. Many of the pines were blackened and torn by shell-fire, and the chalky soil was pockmarked with shell craters from Boche counter-battery work, searching for the French guns camouflaged there. Trenches zigzagged through the pines, old and new, with belts of rusty wire. There were graves.

North from the edge of the pines the battalion looked out on desolation where the once grassy, rolling slopes of the Champagne stretched away like a great white sea that had been dead and accursed through all time. Near at hand was Souain, a town of the dead, a shattered skeleton of a place, with shells breaking over it. Beyond and northward was Somme-Py, nearly blotted out by four years of war. From there to the horizon, east and west and north and south, was all a stricken land. The rich top-soil that formerly made the Champagne one of the fat provinces of France was gone, blown away and buried under by four years of incessant shell-fire. Areas that had been forested showed only blackened, branchless stumps, upthrust through the churned earth. What was left was naked, leprous chalk. It was a wilderness of craters, large and small, wherein no yard of earth lay untouched. Interminable mazes of trench work threaded this waste, discernible from a distance by the belts of rusty wire entanglements that stood before them. Of the great national highway that had once marched across the Champagne between rows of stately poplars, no vestige remained.

The second-in-command, peering from the pines with other officers of the battalion, could see nothing that moved in all the desolation. Men were there, thousands of them, but they were burrowed like animals in the earth. North of Somme-Py, even then, Gouraud’s hard-fighting Frenchmen were blasting their way through the lines that led up to the last strongholds of the Boche toward Blanc Mont Ridge, and over this mangled terrain could be seen the smoke and fury of bursting shrapnel shell and high explosive. The sustained roar of artillery and the infernal clattering of machine-guns and musketry beat upon the ears of the watchers. Through glasses one could make out bits of blue and bits of green-gray, flung casually about between the trenches. These, the only touches of color in the waste, were the unburied bodies of French and German dead.

“So this, Slover, is the Champagne,” said the second-in-command to one of his non-coms who stood beside him. The sergeant spat. “It looks like hell, sir!” he said.

The lieutenant strolled over to where a French staff captain stood with a knot of officers in the edge of the pines, pointing out features of this extended field, made memorable by bitter fighting.

“Since 1914 we have fought hard here,” he was saying. “Oh, the French know this Champagne well, and the Boche knows it too. Yonder”—he pointed to the southwest—“is the Butte de Souain, where our Foreign Legion met in the first year that Guard Division that the Prussians call the ‘Cockchafers.’ They took the Butte, but most of the Legion are lying there now. And yonder”—the Frenchman extended his arm with a gesture that had something of the salute in it—“stands the Mountain of Rheims. If you look—the air is clearing a little—you can perhaps see the towers of Rheims itself.”

A long grayish hill lay against the gray sky at the horizon, and over it a good glass showed, very far and faint, the spires of the great cathedral, with a cloud of shell-fire hanging over them.

“All this terrain, as far as Rheims, is dominated by Blanc Mont Ridge yonder to the north. As long as the Boche holds Blanc Mont, he can throw his shells into Rheims; he can dominate the whole Champagne Sector, as far as the Marne. Indeed, they say that the Kaiser watched from Blanc Mont the battle that he launched here in July. And the Boche means to hang on there. So far, we have failed to dislodge him. I expect”—he broke off and smiled gravely on the circle of officers—“you will see some very hard fighting in the next few days, gentlemen!”

It was the last day of September, and as the forenoon went by an intermittent drizzle sent the battalion to such miserable shelters as the men could improvise. Company commanders and seconds-in-command went up toward ruined Somme-Py for reconnaissance, and returned to profane the prospect to their platoon leaders.

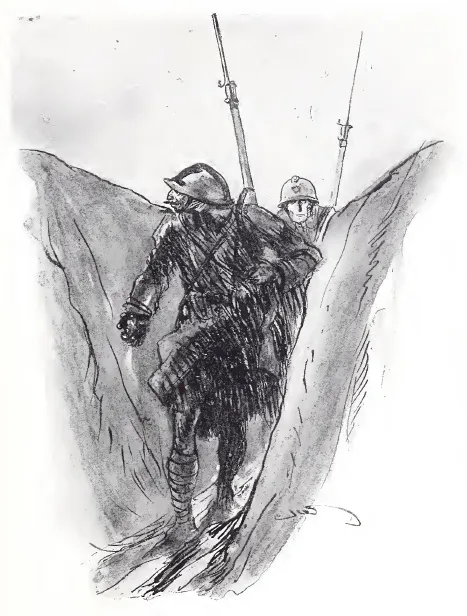

French grenadier—Blanc Mont.

“I do not like this place,” declared the captain of the 49th Company to his juniors. “It looks like it was just built for calamities to happen in.”

“Yep, and all the division is around here for calamities to happen to....A sight more of us will go in than will ever come out of it!”

Meantime it was wet and cold in the dripping shelters. Winter clothing had not been issued, and the battalion shivered and was not cheerful.

“Wish to God we could go up an’ get this fight over with!”

“Yes, an’ then go back somewhere for the winter. Let some of these here noble National Army outfits we’ve been hearin’ about do some of the fightin’! There’s us, and there’s the 1st Division, and the 32d—Hell! we ain’t hogs! Let some of them other fellows have the glory——”

“Gawd help the Boche when we meets him this time! Somebody’s got to pay for keepin’ us out in this wet an’ cold.”

“Hear your young men talk, El Capitan? They’re goin’ to take it out on the Boche—they will, too. Don’t you take any more of this than your rank entitles you to! I’m gettin’ wet.”

The second-in-command and the captain were huddled under a small sheet of corrugated iron, stolen by an enterprising orderly from the French gunners. The captain was very large, and the other very lean, and they were both about the same length. They fitted under the sheet by a sort of dovetailing process that made it complicated for either to move. A second-in-command is sort of an understudy to the company commander. In some of the outfits the captain does everything, and his understudy can only mope around and wait for his senior to become a casualty. In others, it is the junior who gets things done, and the captain is just a figurehead. In the 49th, however, the relation was at its happiest. The big captain and his lieutenant functioned together as smoothly as parts of a sweet-running engine, and there was between them the undemonstrative affection of men who have faced much peril together.

“As for me,” rejoined the captain, drawing up one soaked knee and putting the other out in the wet, “I want to get wounded in this fight. A bon blighty, in the arm or the leg, I think. Something that will keep me in a nice dry hospital until spring. I don’t like cold weather. Now who is pushin’? It’s nothin’ to me, John, if your side leaks—keep off o’ mine!”

So the last day of September, 1918, passed, with the racket up forward unabated. So much of war is just lying around waiting in more or less discomfort. And herein lies the excellence of veterans. They swear and growl horribly under discomfort and exposure—far more than green troops; but privations do not sap their spirit or undermine that intangible thing called morale. Rather do sufferings nourish in the men a cold, mounting anger, that swells to sullen ardor when at last the infantry comes to grips with the enemy, and then it goes hard indeed with him who stands in the way.

On the front, a few kilometres from where the battalion lay and listened to the guns, Gouraud’s attack was coming to a head around the heights north of Somme-Py and the strong trench systems that guarded the way to Blanc Mont Ridge. Three magnificent French divisions, one of Chasseurs, a colonial division, and a line division with a Verdun history, shattered themselves in fruitless attacks on the Essen Trench and the Essen Hook, a switch line of that system. Beyond the Essen line the Blanc Mont position loomed impregnable. Late on the 1st of October, a gray, bleak day, the battalion got its battle orders, and took over a mangled front line from certain weary Frenchmen.

Gathering the platoon leaders and non-coms around them, the captain and the second-in-command of the 49th Company spread a large map on the ground, weighting its corners with their pis...

Table of contents

- Title page

- TABLE OF CONTENTS

- DEDICATION

- INTRODUCTION-THE LEATHERNECKS

- ILLUSTRATIONS

- I-BATTLE SIGHT: THE FIGHTING AROUND THE BOIS DE BELLEAU

- SONG ONE-“BANG AWAY, LULU”

- II-THE CHARGE AT SOISSONS

- SONG TWO-“CARRY ME BACK TO OLE VIRGINNY”

- III-MARINES AT BLANC MONT

- SONG THREE-“MADEMOISELLE FROM ARMENTIÈRES”

- IV-MONKEY-MEAT

- SONG FOUR-“SWEET AD-O-LINE”

- V-THE RHINE

- SONG FIVE-“LONG BOY”

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Fix Bayonets! by Captain John W. Thomason, Jr. in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & Military Biographies. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.