- 176 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Lost Youngstown

About this book

The massive steel mills of Youngstown once fueled the economic boom of the Mahoning Valley. Movie patrons took in the latest flick at the ornate Paramount Theater, and mob bosses dressed to the nines for supper at the Colonial House. In 1977, the Youngstown Sheet and Tube Company announced the closure of its steelworks in a nearby city. The fallout of the ensuing mill shutdowns erased many of the city's beloved landmarks and neighborhoods. Students hurrying across a crowded campus tread on the foundations of the Elms Ballroom, where Duke Ellington once brought down the house. On the lower eastside, only broken buildings and the long-silent stacks of Republic Rubber remain. Urban explorer and historian Sean T. Posey navigates a disappearing cityscape to reveal a lost era of Youngstown.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

Topic

HistoireSubtopic

Histoire de l'Amérique du NordPART I

INDUSTRIAL COLOSSUS

1

YOUNGSTOWN SHEET AND TUBE

For nearly eighty years, the Youngstown Sheet and Tube Company remained the central business institution in Youngstown. Known as “the boss,” Sheet and Tube exerted an outsized influence on the community. Unlike the other steel giants in the area, the company bore the Youngstown name. When literature, advertisements and products went out, they were stamped with the emblem “Quality Youngstown Service.” Formed locally in the early twentieth century, the company gradually expanded to become the fifth-largest steel company in the nation. Sheet and Tube became the centerpiece of the largest merger drama in the history of the steel industry, and it captured the attention of the nation’s highest court when Harry Truman seized the mills during the Korean War. The closing of Sheet and Tube’s Campbell Works in 1977 represented the largest peacetime plant shutdown in American history up to that point; it also marked the beginning of the fall of the nation’s large, integrated steel companies.

The Mahoning Valley’s nascent iron industry emerged in the early nineteenth century. The Mill Creek Furnace, constructed around 1833, was the first iron furnace to open in Youngstown proper. The Eagle Furnace, located just north of Youngstown, followed in 1846. The ensuing discovery of black coal underneath nearby Brier Hill and the building of the Pennsylvania and Ohio Canal enabled the affordable and efficient movement of the much-sought-after “Brier Hill black” coal and other goods from the area’s landlocked location. Mine owners David Tod and Henry Stambaugh used their profits from the mines to invest in and accelerate the growth of the local iron industry. The coming of the Civil War provided an enormous demand for iron products, and the local iron makers prospered accordingly. Soon, the canal closed in favor of the railroad. As iron furnaces sprang up, workers began coalescing around Brier Hill and other early immigrant communities. Youngstown was a “kingdom in iron,” but iron, by the end of the nineteenth century, was rapidly being replaced by steel production.

On November 23, 1900, investors incorporated the Youngstown Iron Sheet and Tube Company. The list of initial stockholders read like a who’s who of prominent citizens: Sallie Todd; George, Henry and Charles Wick; John and Henry Stambaugh; and Paul Powers, among others. The company raised funds to purchase land in a fallow area of East Youngstown (the present-day city of Campbell). Four sheet mills were soon constructed, fourteen double- puddling furnaces, three tube mills and a skelp mill.6 However, Sheet and Tube lacked an adequate process for making steel. Since the first American Bessemer converter began operation in Troy, New York, in the 1860s, steel had been gaining importance in America. Youngstown Sheet and Tube finally built its first Bessemer converter in 1905; for lack of capital funding, open-hearth furnaces remained on the drawing board.

Along with steel’s greater tensile strength, the process of making it proved to be far more efficient and cost effective. Iron puddling was a labor- intensive process of creating wrought iron. Puddlers possessed a valuable skill set, and they commonly worked twelve-hour days, seven days a week, in brutal conditions. Puddlers, however, made reasonably good money and were described as the “cocks o’ the walk” of early industrial workers in the valley.7 As the Bessemer process for making steel and then the open-hearth process expanded, the role of iron and the place of puddlers in the industrial hierarchy decreased markedly.

Citing ill health, George Wick resigned as president of the company soon after it formed. An experienced and driven businessman named James Campbell replaced him as president and chairman of the board. Under his leadership Sheet and Tube dropped “iron” from the company name and began aggressively building an infrastructure capable of competing in the rapidly expanding local steel business.

The company’s Campbell Works in East Youngstown steadily expanded until it ultimately reached almost five miles in length. Campbell, an experienced manager, maneuvered the business through the challenging early phases of growth. He also understood that the next technological step was to construct open-hearth furnaces, as they proved far superior to the Bessemer converter in all but the time needed to complete the process. In 1913, the first open-hearth furnace came online; it joined two existing Bessemer converters. Rapid growth led to rapid employment, and although conditions in the mills largely exceeded those in the old iron companies, problematic living and working conditions led to big clashes between labor and the steel industry.

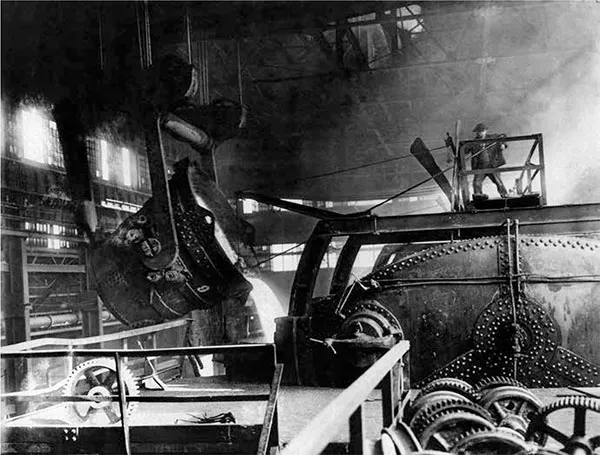

A steelworker labors in the intense heat of a Youngstown Sheet and Tube mill. Courtesy of Thomas Molocea.

Youngstown Sheet and Tube unveiled a new emergency hospital in East Youngstown for workers in 1915. The Italian Renaissance–style structure cost nearly $100,000. The company also started a fund to pay for medical expenses for injured workers; however, the hospital really represented a practical step in the direction of “welfare capitalism.” Executives understood the brutal nature of millwork, and perhaps more importantly, they feared anything that could give unions a foothold in the workplace.8 Yet it would take the disastrous events of 1916 before even minimal changes in work and community life began.

The life of early ironworkers was exhausting and routinely dangerous. According to Mahoning Valley iron and steel historian Clayton Ruminski, death and the possibility of being maimed or permanently injured remained the reality of ironwork.9 The transition to larger and more efficiently run steel mills lessened those dangers, yet early steelwork was still a life lived in a maze of potential peril in the overwhelming world of the integrated mill. Nor could workers look forward to safe and sanitary conditions in the perpetually overcrowded housing market outside the mills.

The original Youngstown Sheet and Tube hospital still stands in Campbell, Ohio. Photo by the author.

Without proper sanitation or paved streets, the hovels of East Youngstown contained a restless population. That restlessness exploded into rage during a strike against Youngstown Sheet and Tube and Republic Iron and Steel in January 1916. An exchange of gunfire between police and strikers resulted in a riot that destroyed four blocks of East Youngstown and resulted in numerous deaths and injuries. The strike itself represented “one of the most dramatic that the country has ever known.”10 In response to the destruction in East Youngstown, Sheet and Tube moved on several fronts to contain worker frustrations.

The company formed a subsidiary, the Buckeye Land Company, to build worker housing in East Youngstown and the city of Struthers. The result in East Youngstown was forty acres of prefabricated concrete apartments. Both fireproof and well-appointed, they represented the first such units ever constructed.11 The company’s efforts extended to providing opportunities for recreation at company-sponsored events, usually held in Campbell (East Youngstown) or at Idora Park. Dances, baseball teams and enormous Labor Day outings—a rare occasion where management and the rank and file mingled—were designed to assuage worker grievances.

In the workplace, Youngstown Sheet and Tube introduced the Bulletin newsletter in 1919. One of the very first of its kind, the Bulletin contained a mixture of gossip, industrial news and items intended to publicize the company’s efforts to make both work and leisure more pleasant for employees. Despite such efforts, strikes and attempts to unionize the mills continued.

Youngstown Sheet and Tube moved into the 1920s under a cloud of merger rumors. The possibility that the Sheet and Tube name might be subsumed in a steel merger filled the local business community with dread. The 1920s only furthered the trend of consolidation in the industry. In 1921, Youngstown Sheet and Tube found itself at the center of a proposed merger with the Brier Hill Steel Company, Inland Steel, Midvale and possibly the massive Bethlehem Steel, among others.

Time and the elements have failed to bring down the original Campbell worker homes, which were the first prefabricated concrete apartments built. Photo by the author.

This former Youngstown Sheet and Tube plate mill building, built in 1918, dates back to the original Brier Hill Steel Company. Photo by the author.

After the proposed merger fell through, James Campbell acquired the Brier Hill Steel Company; part of that company’s facilities became the Sheet and Tube Brier Hill Works. More importantly, the company obtained the Steel and Tube Company, which owned valuable properties on Lake Michigan and just outside Chicago. This acquisition was widely viewed as a hedge against what James Campbell and others saw as the future of the industry: midwestern mills situated on large, navigable water routes.

Despite the early concerns over the future of Youngstown’s landlocked steel mills, the late 1920s represented a heady era locally. In 1927, the Youngstown district was the largest steel producer in the country, and the city’s manufacturing workers earned the highest average wages among similar industrial cities.12 The population swelled at the end of the decade to over 170,000; the city fathers foresaw a future population of 350,000 or more. But as Youngstown reached new heights, more rumors about a possible merger between Youngstown Sheet and Tube and Bethlehem Steel, the second-largest producer after U.S. Steel, set the city on edge.

Bethlehem Steel was a major shipbuilder with an aggressive, expansionist outlook, and Bethlehem came to covet Sheet and Tube’s Indiana Harbor Works, near Chicago. James Campbell, unlike many in Youngstown, sought the merger with Bethlehem, as he feared for Sheet and Tube’s long-term competitive footing. The potential combination drew enormous opprobrium from the public, however. A particularly harsh editorial in the Youngstown Vindicator on March 10, 1930, summed up the situation for many: “Youngstown is face to face with the gravest crisis in its history. Upon the solution hangs the future of this city and the Mahoning Valley for all time to come. This is the question: Shall Youngstown remain a first class city, directing its own affairs and master of its own fate, or shall it allow control to slip from its hands and take orders from somebody else for the rest of its life.”

The deal ran into further trouble when Cyrus Eaton, a large stockholder, began to rally investors in opposition. Eaton’s fortune came from a combination of financial acumen and ruthlessness. Only a few years previous, he orchestrated the formation of the Republic Steel Company, which led to the movement of Republic’s corporate headquarters from Youngstown to Cleveland. Still, Eaton understood the importance of maintaining the Youngstown Sheet and Tube name in the Mahoning Valley. He also maintained a visceral dislike for what he considered to be East Coast business elites in the shape of Bethlehem executives. The collapse of the economy and the deepening of the Depression furthered public opposition to what seemed like a deal made by the same type of people who had helped overheat the economy in the first place. A court injunction halted the deal at the end of 1930, and the biggest potential merger in the history of American steel went up like so much smoke from the mill.

The first years of the Great Depression proved as disastrous for Sheet and Tube as they did for the city. Operations were reduced to less than 25 percent of total capacity, and the seemingly perpetually sullen skies around the mills were suddenly clear. Youngstown gained notoriety nationally as “the hungry city,” and the local government wrestled with how to handle the ever-growing number of unemployed. In Campbell, (East Youngstown had been renamed after James Campbell in 1922) idle workers spent their hours tending “Depression Gardens.” Sheet and Tube maintained over one hundred acres for families to work; every acre held about eight gardens. At least three thousand workers tended such plots during the 1930s.13

Stop 14 in Struthers, Ohio. Courtesy of Thomas Molocea.

While events became increasingly desperate outside, inside the executive offices of Sheet and Tube, management conceived of a daring capital investment. The company already played a major role in the production of pipe. Yet the market for steel sheet, used in manufacturing automobiles, looked like the next sure bet—at least before the Depression. After James Campbell retired in 1930, Frank Purnell became the company’s third president. He believed Sheet and Tube should modernize, even if the foreseeable economic climate seemed to rule out such investments. An experimental hot strip mill and new cold rolling mill capacity came online in Campbell during the Depression. Construction of a new seamless pipe mill in 1938 helped solidify Youngstown Sheet and Tube as the second-largest producer of pipe in the nation.14 But the late 1930s also brought renewed tensions between labor and management.

In 1935, Youngstown Sheet and Tube became the second steel company in the country to offer paid vacations to rank-and-file workers with ten years of service or more.15 Perhaps it represented another effort to appeal to workers who continued to flirt with efforts to unionize the company; nevertheless, laborers across Sheet and Tube’s plants joined employees striking against so-called Little Steel companies (mainly Inland, Sheet and Tube and Republic) in 1937. At the beginning of March, U.S. Steel, after facing sustained pressure from the Steelworkers Organizing Committee (SWOC) and the Congress of Industrial Organizations (CIO), agreed to recognize the steelworkers’ union. As the largest company in the cartel-like steel business, U.S. Steel regularly set prices that affected all other steel companies. It appeared the same would hold true for the recognition of unions; instead, the Little Steel companies refused to follow U.S. Steel’s example and unionize.

Unlike Rep...

Table of contents

- Front Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Dedication

- Contents

- Acknowledgements

- Introduction: The Biggest Little City on Earth

- Part I: Industrial Colossus

- Part II: Third Places

- Part III: Communities of the Past

- Notes

- Bibliography

- About the Author

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Lost Youngstown by Sean T. Posey in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Histoire & Histoire de l'Amérique du Nord. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.