- 256 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

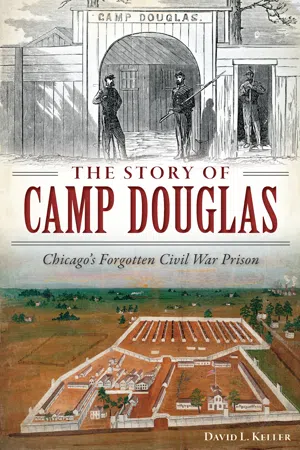

The Story of Camp Douglas: Chicago's Forgotten Civil War Prison

About this book

If you were a Confederate prisoner during the Civil War, you might have ended up in this infamous military prison in Chicago.

More Confederate soldiers died in Chicago's Camp Douglas than on any Civil War battlefield. Originally constructed in 1861 to train forty thousand Union soldiers from the northern third of Illinois, it was converted to a prison camp in 1862. Nearly thirty thousand Confederate prisoners were housed there until it was shut down in 1865. Today, the history of the camp ranges from unknown to deeply misunderstood. David Keller offers a modern perspective of Camp Douglas and a key piece of scholarship in reckoning with the legacy of other military prisons.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access The Story of Camp Douglas: Chicago's Forgotten Civil War Prison by David L. Keller in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & American Civil War History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Chapter 1

The Role of Chicago in the Civil War

Chicago’s Camp Douglas was created as a reception and training center in September 1861. Growing from a population of 108,305 at the 1860 census to 298,997 in 1870, Chicago was the fastest-growing city in the country during the decade of the Civil War. Since the 1850s, the city had been developing its “broad shoulders” with a rich history regarding the question of slavery. It was transforming from a frontier town incorporated less than thirty years before to the most significant city in the West.

Fed by the influx of Irish, German and other European immigrants, along with the nucleus of founding pioneers, the city searched for its identity. More than any city in America, Chicago was defined by the Civil War, which left a mark on the city and its citizens that would remain for years to come. Social restructuring, economic development and Chicago’s role in the conduct of the war were but a few factors that shaped the city.

As it turns out, the leading protagonists of the Civil War—Abraham Lincoln, Jefferson Davis and Robert E. Lee—indirectly established Chicago as the rail center of the West. Eventually, this resulted in Chicago taking the leading role in the West from the older cities of St. Louis and Cincinnati. Rail prominence drove an expanded role for Chicago in the Civil War.

In 1854, the first bridge across the Mississippi River was being built. The Rock Island Bridge was to span the river from Rock Island, Illinois, to Davenport, Iowa. The bridge would connect the Chicago and Rock Island Railroad over the Mississippi River with the Mississippi and Missouri Railroad, leading ultimately to Council Bluffs, Iowa, and the Missouri River. The railway to the developing West from that point on was to come through Chicago. President Franklin Pierce’s secretary of war, Jefferson Davis, was concerned that the bridge was unsafe and should not cross the U.S. military installation at Rock Island. The future president of the Confederacy took this position in spite of the positive recommendation from U.S. Army lieutenant Robert E. Lee that it be built.

More importantly, Davis was concerned that the Rock Island Bridge was placed too far north and would reduce the effectiveness of the South as a transportation hub. He wanted a bridge at Natchez, Mississippi, to serve the Mississippi Delta. Davis took the matter to court in United States v. the Railroad Bridge Company in April 1854. The Circuit Court for Northern Illinois, in Chicago, ruled that the military installation on Rock Island, Fort Armstrong, had been abandoned and therefore the United States had no standing in the court.

The Rock Island Bridge opened on April 22, 1856, with a train of eight cars filled with passengers crossing over to Davenport, Iowa. Subsequently, riverboat interests in St. Louis and New Orleans sued in Hurd v. Rock Island Bridge to stop all bridges over the Mississippi. Abraham Lincoln was engaged by the railroads to defend the suit. Using his personal knowledge of the river and the earlier data compiled by Robert E. Lee, Lincoln presented the case for the importance of east–west travel as equal to north–south river travel. His knowledge of river currents, coupled with Lee’s data and study of the crash of the Effie Afton into the bridge in May 1856, led him to infer that the crash was caused on purpose by the riverboat interests. He prevailed.1

PRO- AND ANTISLAVERY FORCES IN CHICAGO

While Chicago was by no means unanimous in its support of the antislavery movement, significant elements of the city encouraged and were actively involved in the Underground Railroad and the abolitionist movement. In November 1837, early abolitionist Dr. Charles Volney Dyer hosted a public meeting in Chicago to protest the murder of Elijah Lovejoy, editor of the Alton Observer, the leading abolitionist newspaper in Illinois.2 Dyer would go on to be active in the antislavery movement in Chicago throughout the Civil War. He was instrumental in the formation of the Chicago Anti-Slavery Society and in convincing Zabina Eastman, editor of the Genius of Liberty, successor to the Alton Observer, to come to Chicago to become the editor of Chicago’s abolitionist newspaper, Western Citizen.3

In 1851, Deacon Philo Carpenter of the First Congressional Church, along with Dyer, Eastman and other local abolitionists, including famed detective Alan Pinkerton, organized a section of the Underground Railroad that led to the freedom of many escaped slaves.4

John Jones, a free black tailor, and his wife, Mary, were also instrumental in the Underground Railroad in Chicago.5 Jones had come to Chicago in 1845 and by 1860 was one of the wealthiest African Americans in the country. He was a founder of the Olivet Baptist Church that today is located on the northern edge of Camp Douglas. He and Abram T. Hall, a free African American from Pennsylvania, were leaders in the opposition to the Black Codes. These were laws that, among other things, prohibited blacks from suing whites, owning property or merchandise or gaining an education.6 In September 1850, Jones and other African American leaders in Chicago, including Henry O. Wagoner and William Johnson, invoked the proclamations of earlier struggles:

We who have tasted freedom are ready to exclaim with Patrick Henry, “Give us liberty or give us death”…In the language of George Washington, “Resistance to tyrants is obedience to God.” We will stand by our liberty at the expense of our lives and will not consent to be taken into slavery or permit our brethren to be taken.7

While Chicago was considered a hotbed of abolitionism in 1850, the proslavery movement also had strong advocates. The Illinois law making harboring a runaway slave a crime was upheld by the Illinois Supreme Court in 1843. The Chicago Common Counsel, after passing a resolution in October 1850 calling the Fugitive Slave Act “a cruel and unjust law [that] must not be respected,” reversed its position and, after an impassioned presentation by Stephen A. Douglas, who supported the act, repealed its earlier resolution.8 Illinois statutes also included the Black Codes, which severely reduced the rights of free African Americans.9

In addition to Stephen A. Douglas’s support of states’ rights and thus slavery, other Chicago civic leaders, including former mayors Levi Boone (1855–56) and Buckner Morris (1838–39), were noted Southern sympathizers. Both Boone and Morris were imprisoned at Camp Douglas for short periods of time for their Southern sentiments.10 Morris and his wife, Mary, were tried as conspirators for their participation in the Camp Douglas Conspiracy of 1864.11 Southern-sympathizing Copperhead organizations, including the Sons of Liberty and the Knights of the Golden Circle, were also active in Chicago.12

Buckner Morris, mayor of Chicago Mayor from 1838 to 1839. Chicago Public Library.

The passion of the abolitionist movement in Chicago was demonstrated in the city’s reaction to the enactment of the Kansas-Nebraska Act in 1854. This act repealed the Missouri Compromise of 1820, which prohibited slavery in the western territories, and thus opened the territories to slavery. The new act, sponsored by Illinois’s Senator Stephen A. Douglas, supported the concept that inhabitants should determine slavery in their territories. In August 1854, Douglas defended the Kansas-Nebraska Act before nine thousand people in Chicago. When the hostile crowd booed and hissed him, Douglas ended his two-hour justification speech with, “Abolitionists of Chicago! It is now Sunday morning. I’ll go to church, and you may go to hell!”13

Levi Boone, mayor of Chicago from 1855 to 1856. Chicago Public Library.

Without compromising his states’ rights position, Douglas redeemed himself with the Union and Chicago when he unequivocally supported President Lincoln and the war effort after the Confederate attack on Fort Sumter. On May 1, 1861, at the Wigwam in Chicago, he accused the South of a conspiracy. He then asked for Union support, saying, “Every man must be for the United States or against it. There can be no neutrals in this war, only patriots and traitors.” On June 1, Douglas died in Chicago of typhoid fever.14 His final act in support of the Union was a significant factor in Camp Douglas being named in his honor.

CHICAGO AND THE SURROUNDING REGION SUPPLY TROOPS FOR THE WAR

Chicago, the state of Illinois and the surrounding region played significant roles in providing manpower for the Civil War. Illinois ranked behind only New York, Pennsylvania and Ohio in the number of men who enlisted. Almost 260,000 soldiers for the Union effort came from Illinois, with approximately 40,000 of those from the Greater Chicago region and more than 17,000 from the city itself. Nearly 35,000 Illinois soldiers died in the conflict, the third-highest total of all Union states. Throughout the war, Chicago and Illinois consistently met recruiting quotas. During the course of the war and seven calls for volunteers, Illinois provided 237,488 volunteers compared to a quota of 225,791, or nearly 6,000 over the quota.15 Illinois required draft registration; however, between volunteers and the hiring of replacements, virtually no draftees entered the military from Illinois.

In Chicago, as in other places, filling of quotas was not without controversy, even among those who supported the war. In February 1865, a delegation from Chicago headed by Joseph Medill, publisher of the Chicago Tribune, and civic leaders attorney Samuel S. Hayes and Roselle M. Hough (a wealthy meatpacker and former commander of guards at Camp Douglas shortly after the beginning of the war) called on Abraham Lincoln to protest the December 1864 Illinois volunteer quota. They complained that the earlier troops provided by Chicago and Cook County had been undercounted and that the quota should be reduced. After Secretary of War Edwin M. Stanton informed the party that the quota would stand, Medill and the others continued to object. Lincoln tried to convince them that his decision was proper, but as objections continued, he bitterly stated:

Gentlemen, after Boston, Chicago has been the chief instrument in bringing this war on the country. The Northwest has opposed the South as the Northeast has opposed the South. It is you who are largely responsible for making blood flow as it has. You called for the war until we had it. You have called for emancipation and I have given it to you. Whatever you have asked for you have had. Now you come here begging to be let off from the call for men which I have made to carry out the war you have demanded. You ought to be ashamed of yourselves. I have a right to expect better things of you. Go home and raise those 6,000 men. And Medill, you are acting like a coward. You and your Tribune have had more influence than any paper in the Northwest, in making this war. You can influence great masses and yet you cry to be spared at a moment when your cause is suffering. Go home and send us those men.16

In the hallway after the encounter, one of them said, “Well gentlemen, the old man is right. We ought to be ashamed of ourselves. Let us never say anything of this and go home and raise those men.”17 They did.

As Lincoln so well reiterated, the political and business climate in Chicago supported the war effort. Medill’s Chicago Tribune was a longstanding supporter of Lincoln and the Union effort. Only the Chicago Times was an outspoken voice for the anti-war Peace Democrats and Southern sympathizers. Editor Wilber F. Storey and publisher Cyrus Hall McCormick were harsh critics of Lincoln and the prosecution of the war.

In June 1864, Major General Ambrose Burnside, commander of the Department of Ohio (which included Chicago), on his own authority, ordered the suspension of publication of the Times. After significant unrest by Southern sympathizers in the city and communications with President Lincoln, which included a weak petition supporting free speech by William B. Ogden, first mayor of Chicago and head of the Chicago and Northwestern Railroad, a request was made to President Lincoln by Republican Senator Lyman Trumbull and Congressman Isaac N. Arnold to rescind Burnside’s order.

Lincoln, who was unaware of Burnside’s actions and in spite of his personal animosity toward the Times, requested that Burnside lift the ban. On June 4, just before a pro-suppression rally planned by the Republicans, the ban was lifted.18

CIVILIANS IN CHICAGO SUPPORT THE WAR

The civilian population directly supported the war effort—not by being deprived of food and comforts, as happened in the South, but by supporting the troops mustered in in Chicago. Preparation and donation of uniforms, banners and flags were common before the troops went off to war. Women of Chicago were very active in their support of the medical needs of the Union military. When the first prisoners arrived at Camp Douglas in February 1862, the local population was interested in seeing the “secesh.”19 Local women conducted a drive to provide clothing, blankets and food for the prisoners when they first arrived. Churchwomen from Chicago opened a shelter in a renovated hotel for soldiers passing through Chicago in 1863. Before the end of the war, a Soldiers’ Rest building was erected in Dearborn Park.20

The development of the U.S. Sanitary Commission traces its roots to New York, where Unitarian minister Henry Bellows created the basis for ...

Table of contents

- Front Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Dedication

- Contents

- Foreword, by Dan Joyce

- Prefaces

- Acknowledgements

- Introduction

- 1. The Role of Chicago in the Civil War

- 2. Creation and Development of Camp Douglas

- 3. Camp Douglas as a Reception and Training Center for Union Troops

- 4. History of the Treatment of Prisoners of War in America

- 5. Camp Douglas Selected as a Prison Camp and Prisoners Arrive

- 6. Camp Douglas and U.S. Prison Camp Leadership

- 7. Prisoner Exchanges Under the Dix-Hill Cartel and Oath of Allegiance

- 8. Prison Life: Stories and Treatment from the Prisoners’ Perspectives

- 9. Prisoner Health and Medical Care

- 10. Death in the Civil War and at Camp Douglas

- 11. The Conspiracy of 1864

- 12. Reasons for Conditions and Death at Camp Douglas

- 13. Other Union and Confederate Prison Camps

- Epilogue

- Appendix I. Timeline

- Appendix II. Camp Douglas Principal Commanders

- Appendix III. U.S. Army Units Mustered in at Camp Douglas and Guard Units at Camp Douglas

- Appendix IV. Camp Douglas Prison Population

- Notes

- Bibliography

- About the Author