- 176 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

Because they were situated near the Mason-Dixon line, Shepherdstown residents witnessed the realities of the Civil War firsthand. Marching armies, sounds of battle and fear of war had arrived on their doorsteps by the summer of 1862. The Maryland Campaign of September 1862 brought thousands of wounded Confederates into the town's homes, churches and warehouses. The story of Shepherdstown's transformation into "one vast hospital" recounts nightmarish scenes of Confederate soldiers under the caring hands of an army of surgeons and civilians. Author Kevin R. Pawlak retraces the horrific accounts of Shepherdstown as a Civil War hospital town.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Shepherdstown in the Civil War by Kevin R. Pawlak in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & American Civil War History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

“WE LABOR UNDER MANY DISADVANTAGES”

Hundreds of miles from the nearest battlefield, New Yorkers walking along bustling Broadway must have passed under it countless times—a sign with the haunting words “The Dead of Antietam” scrawled on it. Entering the studio of renowned photographer Mathew Brady in October 1862, curious citizens found themselves ascending a staircase to the second-floor exhibit. Once inside the room, “weird copies of carnage” and “pale faces of the dead” met visitors’ unsuspecting eyes.4 Who were these mangled, bloated, sun-beaten corpses in the photographs? They were the tangible embodiment of the struggle that ensued around Sharpsburg, Maryland, on September 17, 1862—America’s bloodiest day.

These images remain some of the most well remembered of the entire Civil War. The familiar images of Confederate corpses lying alongside the Hagerstown Pike, in front of the Dunker Church and inside the Bloody Lane continue to be engrained into the American psyche more than 150 years after Alexander Gardner and James Gibson took them. The several dozen Confederates found lifeless in these photographs are some of the most famous (despite their anonymity) Confederates of the war. Antietam’s photographic legacy stems from these images that showed the American public miles from the war’s bloody fields what war really looked like.

These grisly photographs only demonstrate a slight portion of the Confederate army’s losses at Sharpsburg. Thousands more Confederates that Gardner did not record became casualties on September 17 and, perhaps due to the lack of photographic evidence, have remained in the shadows of history. Yet while New Yorkers along Broadway symbolically experienced “the terrible reality and earnestness of war,” citizens of Sharpsburg, Boonsboro, Hagerstown and Frederick, Maryland, and Staunton, Richmond, Winchester and Shepherdstown, Virginia experienced it physically.5 Indeed, the latter four places became inundated with the comrades of the dead Confederates captured by Gardner’s camera. Until now, studies of Antietam’s victims have focused on Maryland’s citizens caught in the path of war, Confederate dead photographed by Gardner and Gibson and the Federal surgeons and wounded in the field hospitals around the battlefield, which also happen to be extensively photographed. However, the story of the Confederate surgeons and the wounded they cared for—as well as that of the citizens of Shepherdstown, who were first in the path of the mass of Confederate wounded—deserves to be told. Like any Civil War story, it cannot be viewed in a vacuum, for the origins of the story of Antietam’s Confederate wounded and how they fared during the Maryland Campaign of September 1862 begin in early 1861.

Confederate dead along the Hagerstown Turnpike on the Antietam battlefield. Library of Congress.

The idea so famously put forth by Confederate general Nathan Bedford Forrest that “war means fighting, and fighting means killing” would not have had much traction in either North or South in April 1861, as both sides expected a short and relatively bloodless conflict.6 This expectation is reflected in no better way than by examining the readiness of the medical departments of each army for war. For the purpose of this work, we will be looking exclusively at the Confederate medical department.

During wartime, the primary function of a medical department is “keeping the soldier ready for battle and returning him to duty at the earliest possible time after illness or injury.” Historian Horace H. Cunningham notes that both sides were “ill-prepared” to perform this task at the war’s outset.7 The lack of preparation can be partially traced to legislation authorizing the Confederate medical department, which allotted space for only eleven medical officers in the Confederate army and a mere $350,000 for its functions.8 Twenty-three former U.S. Army surgeons constituted the burgeoning medical department, a number clearly too small to accommodate the growing Southern army.9 Size, however, was not the only factor dooming Confederate medical success early. Disorganization, inept medical officers, disease and the small amount of funding led one historian to call the Confederacy’s medical corps “anything but encouraging” by July 1861, the month when the medical department faced its first test.10

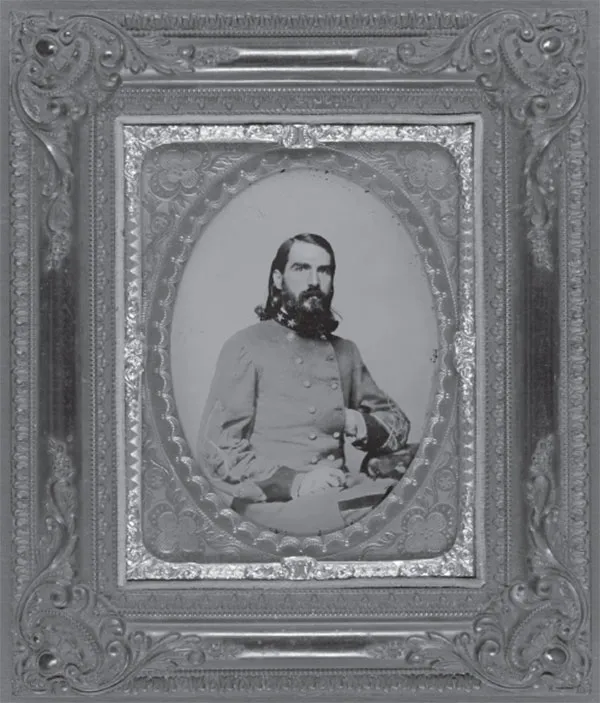

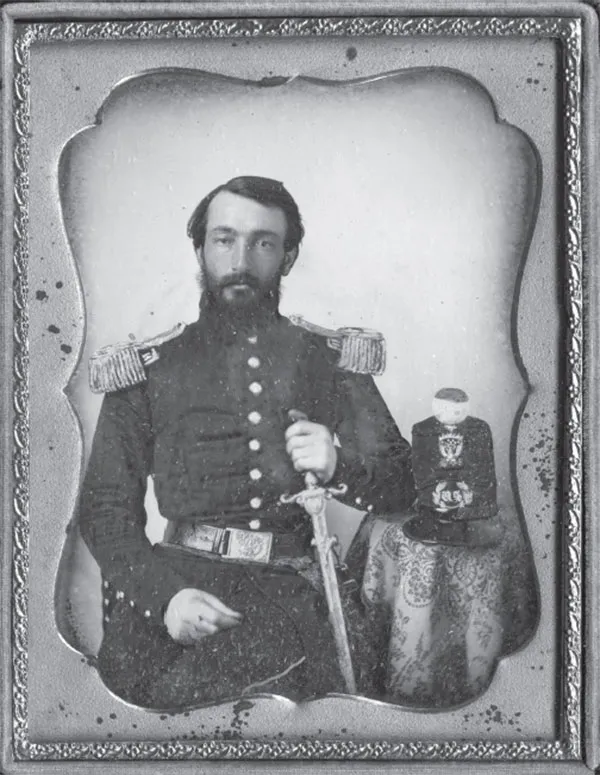

An unidentified surgeon wearing the regulation uniform of a Confederate surgeon. Library of Congress.

Sunday, July 21, 1861, witnessed the first serious bloodshed of the Civil War. In a battle that was branded as the fight to decide the war, Northerners and Southerners clashed on the plains of Manassas in an all-day battle that left approximately 4,800 Americans killed, wounded or missing. Nearly 1,900 of those fell fighting for the Confederacy. Despite the Confederate victory, disorganization ensued enough to prevent a Confederate counterattack.11 The performance of the Confederate medical department, however, was valiant but also disorganized. One Confederate wrote, “Our preparations for the battle, so far as the care of the wounded was concerned, were very imperfect.”12 Perhaps sensing this, President Jefferson Davis appointed Samuel Preston Moore to the post of surgeon general on July 30, 1861. Moore’s family had an extensive medical background, which, along with his efficiency and previous experience, made him a perfect candidate for the position, which he held for the duration of the war.13 Shortly following his promotion, Moore set to work preparing the department for a long, protracted war.

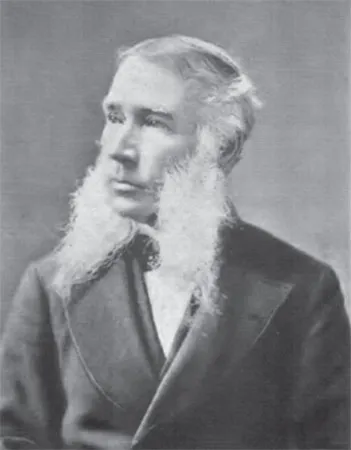

Samuel Preston Moore. From The Photographic History of the Civil War.

Working from a “single room, crowded to overflowing with employees, soldiers, and visitors on business,” Moore began standardizing and professionalizing the Confederate corps of surgeons.14 He established army medical boards that evaluated the readiness of surgeons for duty (and ousted those who were not), began the construction of numerous hospitals in the South and worked to provide the Confederacy with a reliable source of medical supplies.15 All of these improvements better prepared the Confederacy’s medical corps for the spring campaigns of 1862.

The corps’ next call to action in the field came in early April following the Union Army of the Potomac’s move to the Yorktown Peninsula, a campaign conducted to capture the Confederate capital, Richmond. However, the medical department’s resources were tested not only by battle casualties but also by sickness wrought upon the opposing armies. According to one modern study, conditions were so poor on the Peninsula that, at times, approximately 20 to 30 percent of men in each army could be termed “unfit for duty” due to illness.16 Despite the sickness, the two armies continued the campaign and met in pitched battle outside Williamsburg, Virginia. This action, fought on May 5, 1862, had important implications for the Confederate medical department.

Casualties in the sharp engagement amounted to less than those at First Manassas—1,682 Confederates and 2,283 Federals.17 Regardless of the lower numbers, the performance of the Confederate medical corps was worse than it had been ten months earlier. Wounded soldiers were left behind in the Confederate withdrawal, some did not receive any aid and no details were created to remove the wounded from the field in the first place. Two days following the battle, Surgeon General Moore released a circular meant to care “more systematically and effectually for the necessities of the wounded, during and subsequent to engagements.” Hospitals at brigade level would be set up in fixed locations beyond the range of enemy fire, each marked by a flag; each hospital and brigade carried all the necessities of nineteenth-century battlefield medical care; and various infirmary corps, consisting of men detailed from the ranks, were responsible for transporting wounded to the rear. In the sense of removing wounded from the battlefield, the importance of Moore’s directive cannot be understated. “This order stands as a significant milestone along the bloody way of battle and as one which pointed in the direction of more effective field work,” noted one prominent historian.18

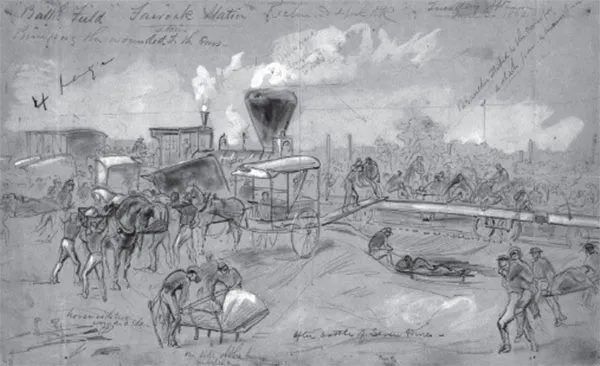

The new system’s first test came several weeks later, ten miles outside Richmond. This time, the bloodletting was the worst yet seen in the war’s Eastern Theater. In two days of fighting near a crossroads called Seven Pines, over 11,000 men fell between the two armies (approximately 8,400 of the 11,000 were wounded).19 When the guns fell silent, the herculean task of caring for the wounded began amid the “groans of the wounded and cries for help.”20 The Confederate medical department performed well in extracting the wounded from the field.21 Most of the Confederate wounded began to funnel toward the major hospitals in the area, all of which happened to be in the capital of the Confederacy. Richmond’s hospitals filled well beyond their capacity, prompting Confederate officers to seize private homes and buildings for hospital purposes. Richmond’s streets, homes and warehouses became “one vast hospital.”22 It was not the last time such a grisly term would be applied to a Virginia community.

Bringing wounded soldiers to the railroad cars after the Battle of Seven Pines. Library of Congress.

Even though the Confederacy’s stewards, nurses and surgeons were getting closer to perfecting a near impossible art, change soon shook the Confederate army and its medical corps following the fight at Seven Pines. Joseph Johnston, the army’s commander, became incapacitated by a wound during the battle and was soon replaced by Robert E. Lee on June 1.23 Lee quickly brought changes to the medical corps, appointing David C. DeLeon as its chief medical officer.24 DeLeon’s stint only lasted twenty-four days, however. On June 27, 1862, in the middle of one of the war’s largest and deadliest campaigns, Lee promoted Alabamian Lafayette Guild to the post of medical director, Army of Northern Virginia.25 For the next few months, Guild would become acquainted with his new position through a trial by fire.

Born on November 24, 1825, in Tuscaloosa, Alabama, Lafayette Guild grew up around the fields of surgery and medicine—after all, his father was a doctor. In 1845, Guild graduated from the University of Alabama before attending Jefferson Medical College, which he graduated from in 1848. While Guild attended lectures there, the dean of the school was future Union army commander George B. McClellan’s father; Army of the Potomac medical director Jonathan Letterman also graduated from that school. The year following his graduation, Guild joined the U.S. Army. Following service in Florida, Guild served as a surgeon at Governor’s Island, New York, where he prevented the spread of yellow fever in the area and thereupon published an influential book about the disease.

Prewar image of Lafayette Guild, medical director of the Army of Northern Virginia. Museum of the Confederacy.

In 1851, Lafayette Guild married Aylette Fitts, a native Alabamian. She accompanied Guild on his next assignment, which took him to the American West, where he remained until the beginning of the Civil War. When hostilities erupted, Guild did not renew his oath to the U.S. Army and became one of twenty-three U.S. Arm...

Table of contents

- Front Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Dedication

- Contents

- Foreword, by James A. Rosebrock

- Acknowledgements

- Introduction: “One Vast Hospital”

- 1. “We Labor Under Many Disadvantages”

- 2. “All Is Terrible Suspense”

- 3. The Woe of the Wounded

- 4. “We Surrender! We Are Wounded Men!”

- 5. Shepherdstown, Hospital Town

- 6. “The Longest, Saddest Day”

- 7. “Like an Awful Dream”

- 8. “I Shudder Even Now, in Recalling It”

- 9. “Their Deeds Are Not Forgotten”

- Notes

- Bibliography

- About the Author