![Air Power For Patton's Army: The XIX Tactical Air Command In The Second World War [Illustrated Edition]](https://img.perlego.com/book-covers/3018630/9781782895008_300_450.webp)

eBook - ePub

Air Power For Patton's Army: The XIX Tactical Air Command In The Second World War [Illustrated Edition]

- 336 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Air Power For Patton's Army: The XIX Tactical Air Command In The Second World War [Illustrated Edition]

About this book

Illustrated with 3 charts, 28 maps and 88 photos.

This insightful work by David N. Spires holds many lessons in tactical air-ground operations. Despite peacetime rivalries in the drafting of service doctrine, in World War II the immense pressures of wartime drove army and air commanders to cooperate in the effective prosecution of battlefield operations. In northwest Europe during the war, the combination of the U.S. Third Army commanded by Lt. Gen. George S. Patton and the XIX Tactical Air Command led by Brig. Gen. Otto P. Weyland proved to be the most effective allied air-ground team of World War II.

The great success of Patton's drive across France, ultimately crossing the Rhine, and then racing across southern Germany, owed a great deal to Weyland's airmen of the XIX Tactical Air Command. This deft cooperation paved the way for allied victory in Western Europe and today remains a classic example of air-ground effectiveness. It forever highlighted the importance of air-ground commanders working closely together on the battlefield.

This insightful work by David N. Spires holds many lessons in tactical air-ground operations. Despite peacetime rivalries in the drafting of service doctrine, in World War II the immense pressures of wartime drove army and air commanders to cooperate in the effective prosecution of battlefield operations. In northwest Europe during the war, the combination of the U.S. Third Army commanded by Lt. Gen. George S. Patton and the XIX Tactical Air Command led by Brig. Gen. Otto P. Weyland proved to be the most effective allied air-ground team of World War II.

The great success of Patton's drive across France, ultimately crossing the Rhine, and then racing across southern Germany, owed a great deal to Weyland's airmen of the XIX Tactical Air Command. This deft cooperation paved the way for allied victory in Western Europe and today remains a classic example of air-ground effectiveness. It forever highlighted the importance of air-ground commanders working closely together on the battlefield.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Air Power For Patton's Army: The XIX Tactical Air Command In The Second World War [Illustrated Edition] by David N. Spires in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & European History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Chapter One — The Doctrinal Setting

The U.S. Third Army-XIX Tactical Air Command air-ground combat team is better understood in light of the doctrinal developments that preceded its joint operations in 1944 and 1945. Well before World War II, many army air leaders came to view close air support of army ground forces as a second-or third-order priority. After World War I the Air Service Tactical School, the Army Air Service’s focal point for doctrinal development and education, stressed pursuit (or fighter) aviation and air superiority as the air arm’s primary mission. Air superiority at that time meant primarily controlling the air to prevent enemy reconnaissance. At least among airmen from the early 1920s, tactical air doctrine stressed winning air superiority as the number one effort in air operations. Next in importance was interdiction, or isolation of the battlefield by bombing lines of supply and communications behind them. Finally, attacking enemy forces at the front, in the immediate combat zone, ranked last in priority. Airmen considered this “close air support” mission, performed primarily by attack aviation, to be the most dangerous and least efficient use of air resources.{1} Even in this early period, the air arm preferred aerial support operations to attack targets outside the “zone of contact.”{2}

Evolution of Early Tactical Air Doctrine

By the mid-1930s, leaders of the renamed Army Air Corps increasingly focused their attention on strategic bombardment, which had a doctrine all its own, as the best use of the country’s emerging air arm. Certainly among senior airmen at that time, tactical air operations ran a poor second to strategic bombardment as the proper role for the Army Air Corps. But this preference for strategic bombardment was not entirely responsible for the decline in attention paid to pursuit and attack aviation. Scarce resources and technical limitations contributed to tactical air power’s decline in fortune. Pursuit prototypes, for example, competed with bombers for resources, and Air Corps leaders hesitated to fund them when they often could not agree among themselves or with their Army counterparts on the desired performance characteristics and engine types. At the same time, the aircraft industry preferred the more expensive bombers for obvious economic reasons, and also because that particular Army-funded development offered technological benefits for commercial aviation.{3}

In attack aviation, the Spanish Civil War demonstrated the high risks of relying on traditional tactics of low-level approach with the restricted maneuverability at that altitude, in the face of improving antiaircraft defenses. Attack aircraft thus had to be given whatever advantages of speed, maneuverability, and protective armor that technology allowed, and they also had to be mounted with sufficiently large fuel tanks to ensure an extended range with a useful bomb load. For single-engine aircraft, this challenge proved insurmountable in the late 1930s. Under the circumstances, civilian and military leaders considered the twin-engine light bomber the best available answer. In the spring of 1939, Army Air Corps chief, Maj. Gen. Henry H. (Hap) Arnold selected the Douglas A-20 Havoc for production. The fastest and most advanced of the available light bombers, it was clearly a major improvement over previous tactical aircraft. Nevertheless, it was neither capable of nor intended for precise, close-in support of friendly troops in the immediate battle zone. The A-20 fell between two schools: airmen criticized its light bomb load while Army officials considered it too large and ineffective for close air support of ground operations. The Army also disagreed with the Air Corps over enlisting pursuit aircraft in a ground support role. According to Air Corps tactical doctrine, pursuit aircraft should not provide close air support except in emergencies. As a result, before 1941 Army Air Corps fighters such as the Bell P-39 Airacobra and the Curtiss P-40 Warhawk, though suited to the close air support role, were seldom equipped or flown with bomb racks.{4}

After 1935, desires for an independent air force, doctrinal preferences, and financial limitations reinforced the airmen’s focus on the strategic bombardment mission. Increasingly, Air Corps leaders relied on bombers rather than fighters in their planning for Western Hemisphere defense. Turned against an enemy’s vital industries, they saw strategic bombing as a potential war-winning strategy. Above all, such a strategy promised a role for an Air Corps independent of direct Army control. For many airmen, a strategic mission represented the key to realizing a separate air force. The Boeing four-engine B-17 heavy bomber that first flew in 1935 appeared capable of performing effective strategic bombardment. Furthermore, in 1935, when the U.S. Army contributed to the revision of Training Regulation 440, Employment of the Air Forces of the Army, it gave strategic bombardment a priority equal to that of ground support. In an earlier 1926 regulation, strategic bombardment was authorized only if it conformed to the “broad plan of operations of the military forces.” If the primary mission of the Army’s air arm remained the support of ground forces, by 1935 the growing influence of the Army Air Corps and the need for a consolidated air strike force resulted in the establishment of General Headquarters (GHQ) Air Force, the first combat air force and a precursor of the numbered air forces of World War II. Although Air Corps leaders might emphasize strategic bombardment, they also upheld conventional Army doctrine, asserting that “air forces further the mission of the territorial or tactical commander to which they are assigned or attached.” Taken as a whole, the revised 1935 regulation represented a compromise on the question of operational independence for the air arm: although the air commander remained subordinate to the field commander, the changes clearly demonstrated the Air Corps’ growing influence and the Army leadership’s willingness to compromise.{5}

German blitzkrieg victories at the beginning of World War II rekindled military interest in tactical aviation, especially air-ground operations. On April 15, 1940, the U.S. Army issued Field Manual (FM) 1-5, Employment of the Aviation of the Army. Written by a board that Army Air Corps General Arnold chaired, it reflected the German air achievement in Poland and represented a greater compromise on air doctrine than did the 1935 Army training regulation. The field manual, however, reaffirmed traditional Air Corps principles in a number of ways. For example, it asserted that tactical air represented a theaterwide weapon that must be controlled centrally for maximum effectiveness, that the enemy’s rear rather than the “zone of contact” was the best area for tactical operations, and that those targets ground forces could bracket with artillery should not be assigned to the air arm.{6} To some unhappy Army critics, the new manual still clearly reflected the Air Corps’ desire to control its own air war largely independent of Army direction.

On the other hand, the 1940 Field Manual did not establish Air Corps-desired mission priorities for tactical air employment, but it did authorize decentralized air resources controlled by ground commanders in emergencies. Although the importance of air superiority received ample attention, the manual did not advocate it as the mission to be accomplished first. Rather, assessments of the particular combat situation would determine aerial mission priorities. Among other important intraservice issues it ignored, the manual did not address organizational arrangements and procedures for joint air-ground operations.{7} Field Manual 1-5 attempted to strike a balance between the Air Corps’ position of centralized control of tactical air forces by an airman and the ground forces’ desire to control aircraft in particular combat situations. Given this compromise approach to air support operations, much would depend on the role of the theater commander and the ability of the parties to cooperate and make the arrangements effective.

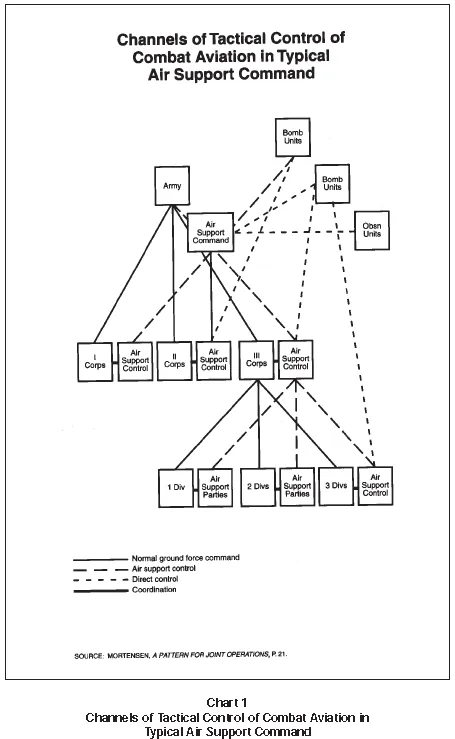

The common theme that emerges from these pre-war doctrinal publications is one of compromise and cooperation as the most important attributes for successful air-ground operations. This theme reappeared in the manual issued following the air-ground maneuvers conducted in Louisiana and North Carolina in 1941 that tested the German system of close air support. In these exercises, newly formed air support commands operated with specific ground elements, but a shortage of aircraft, unrealistic training requirements, inexperience, and divergent air and ground outlooks on close air support led both General Arnold and Lt. Gen. Lesley J. McNair, Commanding General of the Army Ground Forces, to declare the joint training unsatisfactory. Although the air and ground leaders exhibited patience and a willingness to cooperate, that spirit did not always filter down to the lower echelons of command. As a result, despite greater attention paid to close air support in all quarters, the state of air-ground training in the U.S. Army by the spring of 1942 was cause for genuine concern.{8} In response to these shortcomings and the country’s entry as a combatant in World War II, the War Department published FM 31-35, Aviation in Support of Ground Forces, on April 9, 1942. This field manual stressed organizational and procedural arrangements for the air support command. Here, as in previous publications, there was much to satisfy the most ardent air power proponents in the newly designated Army Air Forces (AAF). The air support command functioned as the controlling agency for air employment and the central point for air request approval (Chart 1). Later, in Northwest Europe, Air Support Command would be renamed the Tactical Air Command (TAC) in deference to air leaders in Washington and would support specified field armies. Centralized control of air power would be maintained by collocating air and ground headquarters and assigning air support parties to ground echelons down to the division level. The field manual called for ground units to initiate requests for aerial support through their air support parties, which sent them to the air support command. If approved, the latter’s command post issued attack orders to airdromes and to aircraft.{9}

Field Manual 31-35 of 1942, like FM 1-5 (1940), acknowledged the importance of air superiority and isolation of the battlefield. It also declared that air resources represented a valuable, but scarce commodity. Accordingly, it deemed as inefficient the use of aircraft in the air cover role in which, when they were based nearby or circling overhead, they remained on call by the supported unit. The 1942 manual nonetheless stressed the importance of close air support operations “when it is not practicable to employ other means of attack upon the desired objective in the time available, or when the added firepower and moral effect of air attacks are essential to insure the timely success of the ground force operations.”{10} Despite opposition expressed later by key air leaders, this rationale for close air support would govern the actions of General Weyland and other tactical air commanders in Northwest Europe. On the central question of establishing priorities for missions or targets, however, the manual remained silent, and this would cause difficulty.

In the final analysis, would the ground or air commanders control scarce air resources? The manual’s authors attempted to reach a compromise on this fundamental issue. The 1942 Field Manual declared that “designation of an aviation unit for support of a subordinate ground unit does not imply subordination of that aviation unit to the supported ground unit, nor does it remove the combat aviation unit from the control of the air support commander.” Attaching air units directly to ground formations was judged an exception, “resorted to only when circumstances are such that the air support commander cannot effectively control the combat aviation assigned to the air support command.”{11} Yet “the most important target at a particular time,” FM 31-35 added, “will usually be that target which constitutes the most serious threat to the operations of the supported ground force. The final decision as to priority of targets rests with the commander of the supported unit.”{12} In principle, therefore, air units could be parceled out to subordinate ground commanders, who were authorized to select targets and direct employment. Despite the central position accorded the commander of an air support command and explicit recognition that air assets normally were centralized at theater level, aviation units still could be allocated or attached to subordinate ground units.

Field Manual 31-35 of 1942, like its predecessors, attempted to achieve a balance between the extreme air and ground positions. This manual, however, underscored the importance of close cooperat...

Table of contents

- Title page

- DEDICATION

- TABLE OF CONTENTS

- Foreword

- Editor’s Note

- Preface

- Charts

- Chapter One - The Doctrinal Setting

- Chapter Two - Preparing for Joint Operations

- Chapter Three - The Battle for France

- Chapter Four - Stalemate in Lorraine

- Chapter Five - The Ardennes

- Chapter Six - The Final Offensive

- Chapter Seven - An After Action Assessment

- Sources