- 191 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

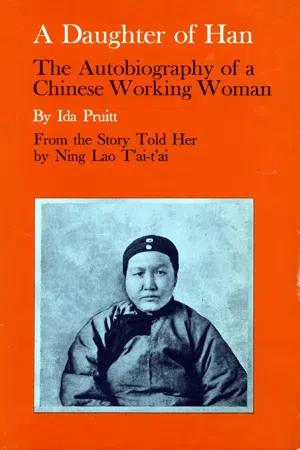

A Daughter Of Han

About this book

Within the common destiny is the individual destiny. So it is that through the telling of one Chinese peasant woman's life, a vivid vision of Chinese history and culture is illuminated. Over the course of two years, Ida Pruitt—a bicultural social worker, writer, and contributor to Sino-American understanding—visited with Ning Lao T'ai-ta'i, three times a week for breakfast. These meetings, originally intended to elucidate for Pruitt traditional Chinese family customs of which Lao T'ai-t'ai possessed some insight, became the foundation for an enduring friendship.

As Lao T'ai-t'ai described the cultural customs of her family, and of the broader community of which they were a part, she invoked episodes from her own personal history to illustrate these customs, until eventually the whole of her life lay open before her new confidante. Pruitt documented this story, casting light not only onto Lao T'ai-t'ai's own biography, but onto the character of life for the common man of China, writ large. The final product is a portrayal of China that is "vividly and humanly revealed."

"This is surely the warmest, most human document that has ever come out of China….The report of her life and labors has the lasting symbolic quality of literature."—The American Journal of Sociology

"No recent book has better portrayed the common man in China….This short autobiography is right in description of Chinese Social customs….In writing this book, Ida Pruitt has rendered a great service to the Chinese people...She has written a personal story through which the spirit of the common people of China is vividly and humanly revealed."—Pacific Affairs

"This book opens a window into the Chinese world. Although the story is of one Chinese woman, the events of her life reach out into the experiences of many other people. They are a part of that wider social and imaginary world from which the Chinese draw meaning to their life."—The Far Eastern Quarterly

As Lao T'ai-t'ai described the cultural customs of her family, and of the broader community of which they were a part, she invoked episodes from her own personal history to illustrate these customs, until eventually the whole of her life lay open before her new confidante. Pruitt documented this story, casting light not only onto Lao T'ai-t'ai's own biography, but onto the character of life for the common man of China, writ large. The final product is a portrayal of China that is "vividly and humanly revealed."

"This is surely the warmest, most human document that has ever come out of China….The report of her life and labors has the lasting symbolic quality of literature."—The American Journal of Sociology

"No recent book has better portrayed the common man in China….This short autobiography is right in description of Chinese Social customs….In writing this book, Ida Pruitt has rendered a great service to the Chinese people...She has written a personal story through which the spirit of the common people of China is vividly and humanly revealed."—Pacific Affairs

"This book opens a window into the Chinese world. Although the story is of one Chinese woman, the events of her life reach out into the experiences of many other people. They are a part of that wider social and imaginary world from which the Chinese draw meaning to their life."—The Far Eastern Quarterly

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access A Daughter Of Han by Ning Lao T'ai-t'ai, Ida Pruitt in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & Central Asian History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

BOOK THREE—THE FAMILY

XII—TOGETHER AGAIN, 1899

MY DAUGHTER Mantze was now fifteen. It was time that she learned to cook and to sew and the ways of a small house, for she must prepare to go to her mother-in-law that she might be settled in life. Also I feared that what she saw in the household of the Ch’ien family would not teach her what was right. And my old opium sot had become more dependable in his later years. He did not now take what I had laid down for a moment and sell it before I could get back. He did not now smoke opium as a regular thing, but never till he died was he entirely free of it. He still drank it also at times. That method is less expensive. The paper in which opium is wrapped is soaked and the water drunk. That is the poor man’s way. But we could live together again. When the lease of the first house I had taken when we moved to the city had run out he had lived from one opium den to another. Then, when I became angry with my mistress of the K’ang Shih yamen and lost my job I had rented a house from Mrs. Chang, and he had lived there. He sold food in front of the district magistrate’s yamen. Mantze cooked it for him and he loaded his baskets and spent his days in front of the magistrate’s yamen. He made enough to pay for his own food and for most of his clothes. In the winter I added a garment or two as he needed them.

With each passing year my old opium sot was more dependable than he had been, but he could not talk without reviling something. It was the fault of his mother, who had not trained him to talk properly. Every other word was a word of abuse. I would say to him, “How you do talk.”

And he would say, “That’s the way I talk.”

One day he was gathering pine cones off the floor to build the fire for cooking. We always used pine cones for our fires. That winter we were raising small chickens. My husband could not see well. He had always been one that peered. He could not raise his eyelids. He thought the little chickens were pine cones and tried to gather them up and so got his hands into their droppings. It made him angry. He began to swear. He said, “Rape this mess of dung.”

Our neighbor standing in the doorway said, “Dung is not a plaything.”

I laughed and said, “There you are, the two of you, contending over who shall play with and who shall rape a piece of dung.”

One day my husband and I had gone to see the lanterns at New Year’s time. I saw a long thing lying on the ground. It looked like an ankle band, “It is not mine,” I said to myself, and went on. My husband stooped to pick it up and it was a snake. The snake was cold and could not move. It had come into the city in a bundle of pine branches that are used for burning under the stoves.

One day while we were living in the house of Mrs. Burns’ cook to watch it for him, a fortune-teller said to me, “You have no fortune. Your destiny is bad. You will marry man after man but always there is bad luck for you.”

He gave me such a bad fortune and I wept so hard that I thought I would die. I said to my old opium sot, “It is no use. I will never leave you since the others are even worse than you.”

It was time that I thought of my daughter’s marriage. I had long determined to get a better husband for her than my parents had got for me. I would not let a professional matchmaker find a mother-in-law for her. I talked the matter around among my friends and relatives. My sister’s daughter’s husband said that he knew the very man. In fact I had seen him myself. He was the son of a sworn sister of my sister and I had seen him once or twice as he came or went with his mother. There were five brothers in his family, the Li family—fine upstanding young men. The oldest was dying of tuberculosis, but the second had married, and this was the third. He was a cobbler in the camp in the Water City where my sister’s son-in-law was a soldier. It was practically a match among relatives, and my heart felt at peace. My daughter was twelve when I made this match. Now she was fifteen and it was time she learned to keep a house.

And so we lived together in the house I had rented from Mrs. Chang and I worked for two years for the foreigners and my daughter kept house and my old man was better than he had been and I let him sleep on my pallet again. We had not been together all those years. But now it seemed to me that we needed children. My daughter soon would be married and go away. Water poured on the ground does not return. There was no son. What would my old man and I do when we were old? Also there was one to carry on the life stream for us.

XIII—WITH THE MISSIONARIES, 1899-1902

THERE had been foreigners living in P’englai ever since I was a child. The first time I had seen the tall man with the black beard I had thought he was a devil and had squatted in the road and hid my head in my arms. But I had gradually become used to them. The gate of our house, when my mother was alive, was only a few gates away from theirs. The room I rented from Mrs. Chang, who believed in their religion, and helped them preach it, had only a wall between my court and theirs. The foreign women had visited my mother while she was alive, and they visited the official ladies while I worked with them. Mrs. Chang had asked me to arrange the visits with my mistresses. And she had suggested me to Mrs. Burns when she wanted a new amah for her baby.

In Chinese families it is the custom for the maids to live in the house of the family they serve, and the family feeds them. In foreign families it is the custom for the maids to go home at night and to eat their own food. And even if the maid was required to live on the compound of the family for whom she worked, still she ate her own food and had a room in the back court away from the family, so that there was a semblance at least of home life. So I was glad to work for a foreign family.

But it is easier to work for a Chinese family than a foreign family. In a Chinese family, the maid brings the hot water in the morning for the mistress to wash, combs her hair for her, and brings in the meals. The rest of the day is the maid’s, to do with what she likes.

After each meal the servants in a Chinese family eat what is left and also what is prepared for them. In a foreign family there is the mopping of the wooden floors. I always thought that should have been a man’s work, but Mrs. Burns made me do it and she made me sweep the carpet. She had to teach me how to take the heavy side strokes of the foreign broom.

Cleaning in a Chinese home is simple—sweeping up the brick-paved floor with a light broom. And the making of beds in a foreign home is very fatiguing. It is hard to please some mistresses who are particular about the making of the beds. Making a Chinese bed is simple. The bedding is folded and laid in a pile on the low bench at the end of the k’ang.

Washing in Chinese families is much simpler too. To wash twice a month is enough for the garments which are not much soiled. We washed in the river whenever we could. Clothes washed in the river water were always whiter and pleasanter to touch than those washed at home. We did not waste soap either, as the modern young people do. One piece of soap would last us several months. The day before we washed we would take the ashes of the pine branches burnt under our kitchen boilers and seep water through them as water is seeped through grain for making wine. We would rinse the clothes in this liquid, and the next day wash them in the river. They would be pleasant to the touch. We would beat them on the rocks and spread them to dry on the banks. The men’s stockings and the foot wrappings of the women we would treat with starch until they were stiff and white and beautiful.

Never had I been asked to wash unclean things until I worked for the foreigner. If a Chinese woman accidentally soils her garments she rinses them out herself before she gives them to a maid to wash. It is better to use paper that can be thrown away than to use cloth that must be washed each month. Also such things we feel are private and each woman keeps such matters to herself. But Mrs. Burns did not care what she used or whose cloth. She even used her baby’s diapers. That to us Chinese was very terrible. No woman will let anyone use the diaper of her son. She is afraid that his strength will be stolen away. There are those who steal the diapers of a healthy child for disappointed mothers who have no sons. They will also steal the bowl and chopsticks out of which the child eats, in the hope of having sons of their own. In the Descendant’s Nest, the hole in the floor by the bed where the afterbirth of sons is buried, they bury the stolen diaper of one family and the stolen bowl and chopsticks of another, to hold the new-born child within the house. The afterbirth of girls is buried outside the window, for girls must leave home.

To work for foreigners was more difficult than to work for Chinese officials, and paid less. The only advantage was that I could live at home. I thought that I would get more money with Mrs. Burns. But though Mrs. Burns paid me three thousand cash a month and the Chinese only one thousand, I saved money with the Chinese and lost with Mrs. Burns. With my Chinese mistress I got my room, my food and that of my child, heat and water. With my wages I bought clothes and saved the tips. I had about thirty thousand cash saved, but I used it all when I started working for Mrs. Burns. I used it for getting my home established, but I got it back working for my former mistress at night when her husband died. Working for the foreigner and living at home, I had to pay rent, pay for my own food and heat and light, as well as for my clothes.

With the foreigner there was no idle moment until I went home, and then I had my own work to do. Mrs. Burns was very exacting and not always just.

She went to Chefoo on a journey and took me along to care for the baby. After we had got started and were in the inn where we had stopped for the first meal, she said, “How are you going to eat?”

I said that I did not know, that I would listen to her words.

“But did you not bring food?” she said.

“No.”

“Did you not travel with your Chinese mistress into Manchuria?”

And I answered that I had. “But what she ate I ate.”

Then said Mrs. Burns, “I will lend you money to buy your food.”

But she gave the boy his food and I did not think this fair. And when we got to Chefoo the eating was not convenient. The missionaries lived on the top of a hill, and the food stores were all at the bottom of the hill. I did not know which shops to go to, nor did I have time to go, I was kept so busy, and so was often hungry. The boy ate with the cook of the family they were visiting, and had an easy time. I was not happy.

One day Mrs. Burns said to me, “Why is it that you are always angry since we came to Chefoo?”

And I told her and she said that such was the custom, and from one word we went to another. It was the first time I had ever passed words with her. Truly had my old mistress said that my temper was bad, and I had tried to restrain it.

But now I was truly angry, and I said, “When we get back to P’englai you can find another woman. I shall find a Chinese position.” She did not think I meant it.

In Chefoo also we had had words about my sewing on Sunday. I was standing by the washhouse door sewing on a shoe sole. The boy was inside doing some ironing. The door of the washhouse was opposite the door of the chapel, and I was watching the worshipers going in. One of the missionaries saw us and told Mrs. Bums that her people were breaking the Sabbath, Mrs, Burns came over to see us. I saw her coming and slipped the sewing up the wide sleeve of my coat. Our sleeves were very wide in those days. But the boy had his back to the door and was intent on the ironing and so she caught him.

She said, “Why do you iron on Sunday?”

“Because you demand clothes.”

“But I do not want them today. You must not iron today. It is the Sabbath.” And so she scolded him.

She did not scold me, for she knew I was not a believer. But she had seen the sewing before I had slipped it up my sleeve, and when we got to her room she asked me not to sew on Sundays where people could see me. And I asked her why, if their God was one that could see everywhere, it should be wrong for me to sew in one place and not in another. Were the laws that were to be kept not God’s laws?

Then one Sunday when I went into her room to make the bed she was mending her son’s stockings. I walked around the bed to the other side where she could see that I could see, and I smiled. And she said, “Ai, but what can I do? Half his leg was showing.” But she never said anything to me again about sewing on Sundays.

At that time we had not yet quarreled. But it added to my feeling, and when we did quarrel I said that I would get a Chinese position when we returned to P’englai. Like a man hanging, killed by his own weight, I insisted on quarreling. I had used all my money, two thousand cash. I had not enough to live on. We came to bitter words.

“Never since I came to China have I hated anyone so much as you.”...

Table of contents

- Title page

- TABLE OF CONTENTS

- ILLUSTRATIONS

- ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

- PROLOGUE

- THE CITY

- BOOK ONE-THE FAMILY

- BOOK TWO-IN SERVICE

- X-WITH THE MOHAMMEDANS, 1895-1897

- XI-WITH THE CIVIL OFFICIALS, 1897-1899

- BOOK THREE-THE FAMILY