- 459 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

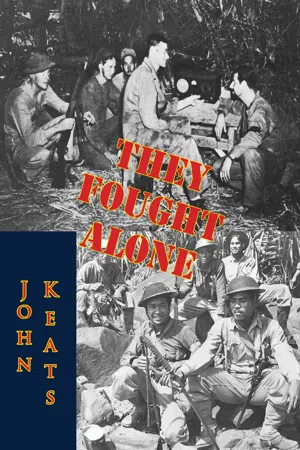

They Fought Alone

About this book

The time: 1942.

The place: The Japanese-occupied island of Mindanao in the Philippines.

The Story: A stirring true account of a man who refused to be defeated.

When the American forces in the Philippines surrendered in May, 1942, a mining engineer named Wendell Fertig chose to take his chances in the jungle. What happened to him during nearly three years far behind enemy lines is the amazing story that John Keats tells in They Fought Alone.

For Fertig, with the aid of a handful of Americans who also refused to surrender, led thousands of Filipinos in a seemingly hopeless war against the Japanese. They made bullets from curtain rods; telegraph wire from iron fence. They fought off sickness, despair and rebellion within their own forces. Their homemade communications were MacArthur's eyes and ears in the Philippines. When the Americans finally returned to Mindanao, they found Fertig virtually in control of one of the world's largest islands, commanding an army of 35,000 men, and at the head of a civil government with its own post office, law courts, currency, factories, and hospitals.

John Keats, who also served in the Philippines, has captured all the pain, brutality, and courage of this incredible drama, in which many memorable men and women play their parts. But They Fought Alone is essentially the story of one man—a testament to the ingenuity and sheer guts of an authentic American hero.

"This remarkable story of guerrilla fighting in the Philippines during WWII...it is absorbing reading. . . . More remarkable still, though it contains death, torture, and desolation, it bubbles with humor." —S. L. A. Marshall, The NY Times Book Review

"A true and admirably researched account of an American hero who refused to accept defeat. His courage was incredible and his resourcefulness equally so. . . . I have read scores of books in this genre and Keats' is one of the best." —Chicago Tribune

The place: The Japanese-occupied island of Mindanao in the Philippines.

The Story: A stirring true account of a man who refused to be defeated.

When the American forces in the Philippines surrendered in May, 1942, a mining engineer named Wendell Fertig chose to take his chances in the jungle. What happened to him during nearly three years far behind enemy lines is the amazing story that John Keats tells in They Fought Alone.

For Fertig, with the aid of a handful of Americans who also refused to surrender, led thousands of Filipinos in a seemingly hopeless war against the Japanese. They made bullets from curtain rods; telegraph wire from iron fence. They fought off sickness, despair and rebellion within their own forces. Their homemade communications were MacArthur's eyes and ears in the Philippines. When the Americans finally returned to Mindanao, they found Fertig virtually in control of one of the world's largest islands, commanding an army of 35,000 men, and at the head of a civil government with its own post office, law courts, currency, factories, and hospitals.

John Keats, who also served in the Philippines, has captured all the pain, brutality, and courage of this incredible drama, in which many memorable men and women play their parts. But They Fought Alone is essentially the story of one man—a testament to the ingenuity and sheer guts of an authentic American hero.

"This remarkable story of guerrilla fighting in the Philippines during WWII...it is absorbing reading. . . . More remarkable still, though it contains death, torture, and desolation, it bubbles with humor." —S. L. A. Marshall, The NY Times Book Review

"A true and admirably researched account of an American hero who refused to accept defeat. His courage was incredible and his resourcefulness equally so. . . . I have read scores of books in this genre and Keats' is one of the best." —Chicago Tribune

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access They Fought Alone by John Keats in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & European History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

BOOK SIX — War

1

Colonel Courtney Whitney read Fertig’s message to MacArthur, which said:

“Part 2 of your 161, received the night of the 28th, decoded and forwarded to me by runner over trail, requiring five hours, arriving my headquarters at 1600 hours after I had already left for rendezvous, 12 kilometers from my Hqs. Message reached beach after launch left for vessel. More allowance should be made for loss of time in transmission of messages. Due to these circumstances, Morgan is en route.”

It was all there: The delay in decoding Part 2. Part 2 was specifically mentioned to add believable detail. The difficulties of the trail —unspecified but left to the vivid imagination. The distances and times all carefully spelled out. Fertig must have worked with a clock in one hand and a map in the other. Then, the blame put on us. It’s our fault for not sending the message sooner. Therefore, it’s our fault that Morgan is arriving.

Colonel Courtney Whitney read on. Amazingly enough, Fertig was giving General MacArthur orders:

“Morgan is not to return here. I must either send him south or execute him to prevent Moro trouble (Charles M. Smith can get sworn statement if needed) as they intended to use his actions against me as excuse for rising against him and his men who in July and August 42 killed Moros promiscuously. This would have meant massacre of every Christian on north coast Lanao. I can possibly control Moros if they do not start killing but once started only Allah can stop them.... In future repatriations, will follow policy exactly.”

Faced with a fait accompli, Colonel Whitney merely endorsed Fertig’s message, and wrote a suggestion for MacArthur’s attention:

“Too bad our message disapproving evacuation of Morgan, Henry and Bonquist arrived too late. Their arrival, particularly that of Morgan, will present a problem but we will work out its solution in a manner that I trust will eliminate any burden on you. At least we will take a big load off of Fertig’s shoulders by having brought these misfits out...”

He filed the papers and concentrated on the next problem—that posed by Captain James Lawrence Evans, MD, the difficult young officer in charge of supplies at the base hospital in Brisbane. Captain Evans’ trouble was that he had too quick a mind. Ordered to turn over a quantity of cholera serum to an intelligence officer, Evans had refused, on grounds the man was asking for serum enough to inoculate more men than there were in the entire army. When the intelligence operative returned to Evans, armed this time with a handwritten order personally signed by General MacArthur, Evans had stuck to his guns. Worse, Evans’ suspicions had been aroused by the fact that an intelligence operative carried such an order. Worse yet, Evans had correctly deduced that the serum was meant to inoculate a population, rather than an army, and had asked the intelligence officer whether this was not so. Worse still, Evans had told the officer that he was tired of being a pill dispenser; that he wished to fight a war, and insisted on being the medical officer assigned to accompany the serum to its mysterious destination.

Obviously, unless something was done quickly about Captain Evans, the cat would be out of the bag. There were plenty of things that could be done, but Colonel Whitney decided to put Evans into the bag with the cat. Indeed, Captain Evans’ unique talents made such a course inevitable, for in addition to being a surgeon, desirous of adventure, Captain Evans held a ham radio license. Or so, at least, the Evans 201 file said. Clearly, a chat with the young man was in order.

During the conference that followed, Colonel Whitney sized up the slim doctor’s athletic appearance, and his quick and fearless replies.

“You understand that everything we have discussed in this room is secret, and not to go out of the room? That you are not to discuss, suggest, or imply to anyone anything that you might have learned or guessed from anything I have said?” Colonel Whitney asked.

“Yes, sir,” Evans said. “Then it’s all set?”

“You will return to your duties,” Colonel Whitney said.

Evans’ face was stricken with disappointment.

“Is that all?” he asked.

“That is all,” Colonel Whitney said.

Captain Evans’ life resumed its normal, monotonous course among the medical inventories. Weeks passed. And then, one night, in the small hours before dawn, Evans was awakened in his tent by men with hooded lamps who gestured him to be silent. Evans sat up, groping for his clothes. They were gone. His shoes were gone. His uniforms, his footlocker. Gone. He was handed navy work clothing. As he dressed, his visitors silently dismantled his mosquito bar, folded his blankets; folded his cot. It was all done quickly, and Evans’ tent mates were not awakened. Within five silent minutes, the personal corner of the tent that had been inhabited by the particular, unique human warmth the world knew as Evans was simply a blank space. Shivering with the morning chill, and with apprehension, Evans wondered what his tent mates would think when they woke to find nothing at all in his corner.

His visitors led Evans through camp to a company street where an army jeep and a navy truck waited. Evans’ effects were put into the jeep. He was loaded in the truck. All the rest of that day, Evans sweated with a navy work gang, loading supplies into the largest submarine he had ever seen. When the loading was complete, and he was about to leave with the stevedores, someone touched his arm and drew him aside. Another man of Evans’ build, in identical, soiled navy work clothes, took Evans’ place in the departing work party, so that if anyone had been counting the number of stevedores who had gone aboard, he would have seen exactly that number return ashore.

Hours later, the USS Narwhal, the largest submarine in the world, was running submerged due north. In the officer’s wardroom, Captain Evans was meeting her skipper, Captain Frank Latta, and a stocky deeply tanned man who wore an air of sleepy charm and endlessly flipped and caught a Chinese silver dollar.

2

“Do you think they really mean ninety tons on one submarine?” Hedges asked.

“We checked the message,” Fertig said.

“And room for sixty passengers going south?”

“It must be a hell of a submarine.”

“I still say we ought to bring it in here.”

“Ninety tons of supplies is a lot of supplies,” Fertig said. “Twenty times more than we have had to handle at one time.”

“My boys can handle it,” Hedges said.

“Sure they can,” Fertig said. “But not easily, and not safely. It takes time to get that much stuff out of the sub and into the boats, and out of the boats and onto the beach. To clear it from the beach in one load, we’d need thirty-five hundred men, to put it on their backs and carry it over the hills. But if we bring the sub into the river mouth, we can load the stuff right onto barges and move it up the river, into the back country, a hell of a lot faster, farther, and with fewer men.”

“Christ, I know that,” Hedges said. “But I still say it would be safer to bring it in here. You’re going to have women and children going out on that sub. What if the Japs hit us? McClish’s outfit can’t give you the protection my boys can.”

“That’s another reason for moving there,” Fertig said. “It’s time we found out just what is wrong with that outfit.”

The two friends studied the map of Mindanao, which Fertig had divided into six separate areas that more or less conformed to the provincial boundaries. Each area was garrisoned by a different guerrilla division, although the word division was more of a military courtesy than a description. Lanao province, home of Hedges’ 108th Division, primarily consisted of wild mountains and a narrow seacoast embraced by headlands garrisoned by Japanese. When a submarine came in on the Lanao coast, it had a Japanese garrison fifteen miles away on one side of it and another Japanese force fifteen miles away on the other.

The Zamboanga Peninsula, including Misamis Occidental, the area of the 105th Division, was too easily divisible from the rest of the island to serve as a center for the distribution of supplies, even if the Japanese had not now been there in force, still hunting for Fertig’s headquarters.

Cotabato was an immense province, but hardly advantageous, for there were not only plenty of Japanese troops in residence but too many pro-Japanese Moros, and the position of Pendatun, commander of the 106th Division, was by no means clear. Rumor said that Pendatun was trying to sign a truce with the Japanese.

Davao, future home of 107th Division, was out of the question. The province was dominated by Davao City, which even before the war had been the largest Japanese city outside the home islands. In Davao before the war, Japanese children had gone to schools that flew the Rising Sun flag, rather than the United States or Philippine Commonwealth flags. The people of Davao City were not merely pro-Japanese, they were Japanese. Davao province was the site of the Japanese sea and air staging bases for the campaigns of the South Pacific.

One of the troubles with Bukidnon province, home of the 109th Division, was that its seacoast, Macajalar Bay, was firmly Japanese. The Bukidnon seaport, Cagayan, was the second-ranking enemy base on Mindanao, and the Japanese Army Air Force occupied the airfields of Del Monte plantation, on the plateau above the city. Moreover, the national road of Mindanao split through the Bukidnon and this road was in Japanese hands.

This left Agusan province, and the 110th Division of Ernest McClish. The area—and indeed the entire island—was dominated by the meandering Agusan River and its dendritic tributaries, a huge complex of waterways. Supplies could be brought up from the sea as far as barges could go, and then barrotos could take barge loads even farther upstream and up the tributaries. Back trails led everywhere from the interior to the barrios on the banks of this natural highway. Supplies could move upriver, and then over back trails to the guerrilla commands. Much as Hedges hated the thought of Fertig’s moving to Agusan, Hedges could see that the map left no choice. Simple geography made Agusan inevitably the site of a guerrilla headquarters.

“If it hadn’t been for Morgan, I’d have gone there when the Japs ran me out of Misamis,” Fertig said, looking at the map. “But as long as we had to worry about him, I wanted to be close enough to handle him, but with your outfit as bodyguard.”

“What the hell,” Hedges said. “I can see it. Particularly about those supplies. That was a hell of a thing, when we lost Knortz and all that ammunition.”

“Ball’s still broken up about it,” Fertig said. “He thinks we’re a pretty chickenshit outfit.”

The two friends fell silent, remembering the handsome, golden-haired Knortz, who had been everyone’s idea of a hero. Absolutely unafraid, glorying in hand-to-hand combat, Knortz had done a marvelous job in bringing rival guerrilla chieftains of Surigao province into line. He had gone among them in what became known as his pacification uniform, which included a Browning automatic rifle, bandoliers of ammunition, a bolo, and crossed gunbelts, stuffed with ammunition, that supported two Colt .45-calibre automatic pistols. Thus armed, and carrying a sheer load of metal that would have foundered a lesser man, Knortz presented a formidable appearance. But his bare hands were dangerous weapons. Persuading when he could, and administering physical beatings when he could not, Knortz had singlehandedly cleaned out bandit gangs. He had led attacks on Japanese patrols, and McClish had made him a captain. But a few days ago, Knortz had drowned when a sudden storm at night swamped the overladen motor launch he had been trying to take across Gingoog Bay. In his youth and his pride, Knortz had died trying to swim in a storm while wearing his guns.

To Fertig, however, the point was not Ball’s grief, nor the poor judgment of Knortz, nor even the loss of the supplies on the launch. It was simply that the Japanese, aroused by the arrival of the submarine that had taken Morgan out, had been patrolling the coast so diligently that Knortz had been forced to dare a storm at night. There was as yet no large Japanese installation on the Agusan coast. If unprecedented quantities of material were to arrive, and if he was also to send safely out the American refugee families hiding in the back country, Fertig should establish himself on that relatively empty coast as soon as possible.

“I’m going to establish a secondary headquarters and radio station at Misamis,” Fertig told Hedges. “I’m going to put Bowler in charge of it. He will take over if anything happens to me.”

Then quickly, seeing the hurt in Hedges’ face, Fertig said:

“By all rights, you should be second in command. I’ve never met Bowler, and I know you. But, Charley, I need you here in Lanao. Somebody’s got to be mother and father and God Almighty to fifteen thousand Moros, and you’re the only one who can be that.”

“You know it doesn’t make a damn bit of difference to me, Wendell,” Hedges said, although it did.

“Well, that’s fine,” Fertig said, although it wasn’t. He was glad that he did not have to tell Hedges why he felt he could not name him as his successor.

The trouble was, Hedges was not called Colonel Goddamn for nothing. Too many Filipinos and Americans hated Charley’s guts, complaining that Hedges not only drove men too hard but sometimes drove them with his fists. Hedges’ temper might not only lead him into trouble, but Hedges might run the command into trouble by his habit of asking as much of his men as he asked of himself. Besides, although Fertig knew Bowler only by reputation, the reports of mutual friends, and by radio messages, everything he had heard of him was good. Moreover, Bowler was a trained army officer, a lieutenant colonel, and Hedges was not.

“I’ll meet Bowler on my way to Agusan,” Fertig said. “I’l...

Table of contents

- Title page

- MAPS

- TABLE OF CONTENTS

- PREFACE

- A NOTE ON FOOTNOTES

- BOOK ONE - Surrender

- BOOK TWO - Decision

- BOOK THREE - The Dragon’s Teeth

- BOOK FOUR - Harvest

- BOOK FIVE - Morgan

- BOOK SIX - War

- Envoi

- Appendix

- The Author