![]()

1

INDIAN CHIEFS and red man warfare have written their stirring saga into American history though to many of today’s readers James Fenimore Cooper’s forest redskins have been far overshadowed by the Plains Indians, the “heavies” of countless western novels and motion pictures, as well as the heroes of some stories and an occasional photoplay.

One making a survey of Indian leaders in the United States will soon find himself becoming familiar with such names as Powhatan, the Great Sachem of Virginia, who had eleven daughters and twenty sons and whose most famous child was the Indian princess, Pocahontas; Opechancanough, the scourge of Virginia, the younger brother of the famed Powhatan and Chief Sachem of the Chickahomminies; Sassacus and Uncas, rival chieftains of the Pequot Rebellion, and the latter the Mohegan ally of the Connecticut settlers; King Philip of “King Philip’s War;” and the Ottawa leader against the British, mighty Pontiac; Massoit, chief of the Wampanoags and friend of the Puritans; Red Jacket, the great warrior of the Senecas; and Logan, the mighty orator and warrior of the Mingoes, betrayed by certain white men in return for his friendship to the invading race.

One would have to recall Captain Joseph Brant, the warrior chief of the Mohawks; Little Turtle, the Miami conqueror of St. Clair; the heralded Tecumseh, Shawnee soldier, diplomat and orator, ally of the British in the war of 1812; Weatherford, the Creek conspirator and fearless fighter; Black Hawk, the leader of the Sacs and Foxes and top warrior of the Black Hawk Rebellion; Osceola, the Creek leader of the Seminoles defeated only by means of a white flag violation in the Florida War; Roman Nose, the Custer of the Cheyennes; Geronimo, the wily Apache who led the cavalry many a chase; and Sequoyah, the amazing genius of the Cherokees, son of a Dutch ancestry Indian trader and a Cherokee mother, who was granted a literary pension of $300 a year out of the Cherokee National Treasury, probably the initial literary pension in American history and most assuredly the first and only one to be granted by an Indian tribe.

Then there are Red Cloud, the tall, eloquent fighting chief of the Ogala; Chief Joseph of the Nez Perce up in the Pacific Northwest and the mighty Sitting Bull, general of the Great Sioux Rebellion with its epic Indian victory over Custer at Little Big Horn, and his able lieutenant Crazy Horse, and Quanah Parker, eagle of the “Lords of the Plains,” the Comanches.

Yes, anyone who has “read up” on the Indians will recognize all these names of outstanding fighters and leaders and he’ll be acquainted with many in addition whose contributions to history are somewhat comparable.

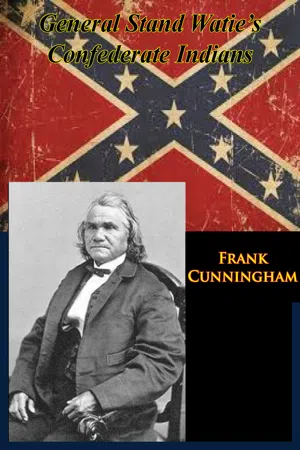

Yet, will he know the story of the three-quarter Cherokee statesman and fighter who was the Principal Chief of the Southern Cherokee, who was the major Indian leader on the side of the Confederacy in the War for Southern Independence, and who rose to be a Brigadier General in the Secessionist army? And whose name and exploits were at one time as feared in the strifetorn lands of the border as those of Charles Quantrill!

A fearless raider about whom Sherman J. Kline, in an article in the Americana, said, “His operations have been likened to those of Francis Marion, who conducted many successful raids in South Carolina during the Revolutionary War, and who became widely known as the ‘Swamp Fox.’ “

James Street in The Civil War, when he mentioned his favorite Confederate generals, wrote, “Gimme Old Jack Jackson or Nathan ‘ygod Bedford Forrest helling for leather. Or Stand Watie, the Cherokee. Who can help loving a man with a name like that—General Stand Watie.”

A man on whose death in 1871, Judge John F. Wheeler wrote in the Fort Smith, Arkansas, Herald: “He was never known to speak an unkind word to his wife or children. He was never morose under any circumstances, and was kind to a fault. His house was the home of every Cherokee...there never lived a better man...”

Even after April 9 at Appomattox Court House where the immaculate gray-clad Robert E. Lee, after having received a message from General John Gordon...“my command has been fought to a frazzle, and I cannot long go forward,” commented grimly, “There is nothing left for me to do but to go and see Grant, and I had rather die a thousand deaths;” even a few days later, on April 18, after Joseph E. Johnston surrendered the Army of the South to William T. “scorched earth” Sherman near Durham Station in North Carolina; indeed even after E. Kirby-Smith, known as “the last Confederate General to surrender”—(actually by General Simon Bolivar Buckner who had replaced Kirby-Smith)—had hauled down the Stars and Bars of the Army of the Trans-Mississippi in May and the vast undefeated Rebel Texas lands fell; yes, after all these Southern capitulations, this Confederate Indian leader still held out!

Despite the verdict of most histories, E. Kirby-Smith was not the last Confederate General to surrender. Edward A. Pollard, editor of the Richmond Examiner, wrote in his book, The Lost Cause, that “With the surrender of General Smith the war ended, and from the Potomac to the Rio Grande there was no longer an armed soldier to resist the authority of the United States.”

But there was!

This Indian General kept holding out. A short time previously he speculated that even though the South had lost in the West, the East and the Deep South, Kirby-Smith had some 36,000 well-fed troops with the possibility that this force could be raised to 90,000 if the still fighting, but retreating C.S.A. soldiers could reach Kirby-Smith’s territory.

This Indian General was so resolved that the Indian allies of Richmond could win out over their enemies—both white and Indian—that even at the time of Lee’s abandoning the struggle he was preparing to raise an army of 10,000 men to invade the abhorred abolitionist land of Eastern Kansas.

Yes, one Confederate Army brigade refused to quit! This was the Indian Brigade with headquarters in the Choctaw Nation, commanded by a warrior small in stature, of little talk but an eloquent writer, and with strong lion-like features that heralded the innate courage which never ordered a charge that he did not lead.

This was a man born December 12, 1806 at an old home on the Coo-sa-wa-tee stream, near the present site of Rome, Georgia; a man at birth named either Ta-ker-taw-ker, meaning “to Stand Firm—Immovable,” or De-gata-ga, conveying the meaning that two persons are standing so closely united in sympathy as to form but one human body. He was the son of Uweti, also known as David-oo-Wa-tee, and Susannah Reese. His mother was one-half white, a member of the Moravian Church, and a descendant of the well-known Reese family of North Carolina and Georgia.

Skilled as a ball player and an excellent rider, the lad soon became known as Stand, though he spoke only his native tongue until he was twelve, and his companions at the Brainerd Mission School in Tennessee little realized that he was to grow up to be one of the foremost names in the history of the Cherokee Nation, a name that, alas, has been obscured by the passing years, perhaps because of the bright light brought forth by the same Sequoyah for, as the Creek Indian poet and editor of the Muskogee Morning Times, Alex Posey, wrote in his Ode to Sequoyah:

“The names of Watie and Boudinot—

The valiant warrior and gifted sage—

And other Cherokees, may be forgot...”

But the name of Brigadier General Stand Watie, the only Indian General in the service of the Confederacy, should ever stand in the front ranks of those who revere the dauntless courage of the men of the Confederacy, men such as General Jo Shelby, who rode into Mexico rather than surrender, and who would say to their scouts returning to report on the enemy:

“Did you see them?”

“Yes, General.”

“Did you count them?”

“No, General.”

“Then, suh, we’ll fight them, by heaven!”

Morris L. Wardell wrote in his Political History of the Cherokee Nation that in rating the entire Indian leadership in the War between the States that General Watie stood out as the most prominent, the most highly respected and the most aggressive, certainly as high a tribute as could be paid the Confederate leader.

And Confederate General Douglas H. Cooper, who finally rose to command all the Indian troops, said after the war’s end, “General Watie was not only a soldier, brave and efficient and courageous, but he was a great man, whose honor and integrity were above reproach.”

As with all the Confederate leaders, defeat continually could not be staved off and in late June 1865, General Stand Watie struck his colors to Lieutenant Colonel Asa C. Matthews, at Doaksville, which had been the capital of the Choctaw Nation from 1850-63; the last Confederate General to surrender!

Behind him were the battles and skirmishes in which his Indian Army of battling mixed-breeds, chiefs of whom had lived as Southern gentlemen, with prosperous plantations, expensively furnished, with faithful white wives who dressed in fancy silks to match their husbands’ frock coats and high hats, with slaves, many of whom remained true to their masters, and a passionate devotion to States Rights not exceeded by the most ardent South Carolinian, had marked—sometimes with shotgun and tommy-hawk—a bloody campaign encompassing such places as Wilson’s Creek, Bird Creek, Pea Ridge, Spavinaw, Newtonia, Fort Wayne, Fort Gibson, Honey Springs, Webber’s Falls, Poison Spring, Massard Prairie, and Cabin Creek.

The Five Civilized Tribes which backed the Confederacy—though such action split the Indian Nations into warring factions in some cases—lost more men in proportion to the number enlisted than any Southern state.

Who can question whether these deaths were in vain for Mabel Washbourne Anderson wrote in Life of General Stand Watie, a slim volume first published in Oklahoma in 1915 and now practically unobtainable in the book market:

“Sherman’s terrible raid, on a smaller scale, might have been repeated in the Indian Territory and Texas had it not been...for General Watie and his command. His brigade was like a stone wall between Texas and the foe.”

Had Watie’s stout but sinewy defense in the Indian Territory been broken and his headquarters in the Choctaw Nation smashed, the horror of the Southern hated Sherman, who had been a college president in the South before the war, could well have been over again, for along with the white Northern troops, the foes of the half-breed Indians who fought under the Confederate flag were the full-blooded Indians—the despised Pins who were loyal to the Union. Whether to line up for Lincoln or Davis was not the first question on which the rival Cherokees had taken sides—and arms—and blood!

And to tell the whole story of this little known part of the War between the States one must delve briefly into Cherokee history.

![]()

2

ORIGINALLY, THE CHEROKEES, had been the allies of the British. They had sided with the English in early Colonial struggles, fought a Border war in the South around 1760, but sued for peace after fourteen of their villages burned.

G. E. E. Lindquist in The Red Man in the United States, wrote:

“The Cherokee Indians of North Carolina have behind them probably a longer history of white civilization than any other tribe. Eight of their chiefs returned to England with Oglethorpe after his expedition of 1733. Two years later Wesleyan missionaries were made welcome by the tribe. Their first treaties with the white man were made with George III and their earliest diplomatic relations with the United States came in 1785 when boundaries were established and 15,000 families were settled on Cherokee lands by the treaty of Hopewell. As early as 1800 the Cherokees were manufacturing cotton cloth. Each family had a farm under cultivation. There were districts with a council house, judge and marshal, schools in all villages and churches of several denominations. Many of the Indians were Christians and were said to lead exemplary lives.”

Edward Everett Dale discussed in Oklahoma—a Guide to the Sooner State the fact that the Indians of the Five Civilized Tribes were alertly cognizant of the favorable geographic position of their lands—east of the Mississippi—and they were adept at playing nation against nation in an effort to hold a balance of power. This involved France, England and Spain as well as Florida, Louisiana, the Carolinas and Georgia.

Scotch families had emigrated following the uprising of 1745 and in the Revolution many of these people had remained “true to the old flag.” When the Continental Army triumphed, a large number of the Loyalists fled into the Cherokee country and the unmarried men soon were husbands of the Cherokee women, frequently Christians as the Moravian Church had been in the Cherokee country since 1740. It was the white blood—so often of the best Scotch families—which was to produce the aristocratic mixed-bloods who were to play the most prominent roles in coming Cherokee history.

After General Pickens had subdued their Tory tendencies, the Cherokees acknowledged the sovereignty of the United States by the Treaty of Hopewell, signe...