- 331 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

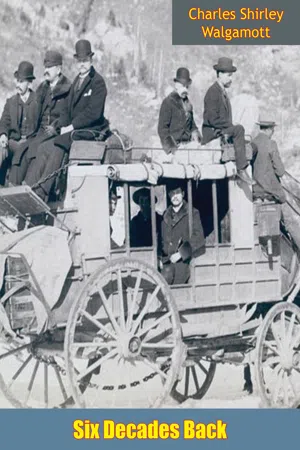

Six Decades Back

About this book

Charles Shirley Walgamott arrived by stage at Rock Creek Station, Idaho Territory, on August 8, 1875. In an untamed land, far from his native Iowa, he survived illness, hardship, and lawlessness with his humor intact. Never a stranger to work, Walgamott mined, trapped, ranched, and hunted. While living with settlers, Indians, and outlaws alike, he amassed a trove of unforgettable experiences.

First published in 1936, this one-volume book represents a collection of his fascinating stories, which were published in the mid-1920s.

"A glowing, colorful, and interesting section of the true frontier....stories exceptionally well done, for every one of them has pith and point and is effectively told."—The New York Times

First published in 1936, this one-volume book represents a collection of his fascinating stories, which were published in the mid-1920s.

"A glowing, colorful, and interesting section of the true frontier....stories exceptionally well done, for every one of them has pith and point and is effectively told."—The New York Times

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

PART I—FALLING IN LOVE WITH IDAHO

WHAT THE WEST SAID TO ME

I WAS THE ONLY BOY in a family of seven, three older and three younger than myself, living in a small town in south-eastern Iowa where my parents settled in 1843; and a germ of frontier longing was early injected into my young blood.

As I listened to stories told around our fireside by my father and mother, relating the happenings of the early days in Iowa and my father’s boyhood experiences as a leader of a string band (now called an orchestra) playing on the lower Mississippi River steamboats; and later when my older sister with her husband staged to California in the employ of the Ben Halliday Stage Company, and my sister made frequent visits back home, bringing with her the atmosphere of the West, this germ of frontier longing developed into a pronounced case of Western fever that proved as contagious as it was pronounced, and was contracted also by a boyfriend.

The two of us made hasty preparation to depart over the Chicago and North-western Railroad, which had recently laid rails as far west as Council Bluffs, where it bridged the Missouri River and landed us in the frontier town of Omaha, Nebraska, to mingle with a crowd of emigrants seeking passage westward over the newly constructed Union Pacific Railroad. I was surprised to find in this crowd of twelve or fifteen cars of emigrants, bound westward, only two women. Both were en route to meet their husbands in California, while my friend, John Garber, and myself were the only two passengers en route for the Idaho territory.

On the platform of the Union Pacific Depot an old man with a long gray beard and gentlemanly appearance was employed by the railroad company as train director and entertainer. I remember that his name was Captain White. I had considerable conversation with him. He told me a great deal about Idaho, informing me where we left the train to take the stage, and about the bad Indians and the still worse white men. After we were placed in our cars and almost in readiness to start, the Captain passed through the train, accompanying his voice with a guitar, and singing all about the West. As he approached the seat which my friend John Garber and I occupied, he improvised the words of his song to describe Idaho. I remember the chorus ran like this:

Hurrah, hurrah for the U.P. Road and a ride over the rolling plain;

We are going out to Idaho and intend there to remain.

One of the verses in doggerel was to this effect:

And if the Indians capture you, you will be lucky to save your head;

They have a habit of taking your scalp unless your hair is red.

As Captain White gracefully dropped out of sight, the train slowly crept out of the siding onto the main line, heading into the mysterious West, with all on board in happy expectation except my friend Johnny, who was truly a homesick boy. He had seen all the West he wanted. Captain White’s song description of Idaho had had a bad effect on him.

As our train for hours each day plowed slowly over the western plains, we were aware that on account of the newness and unballasted condition of the road it would take several days to reach the mountains. We were thankful when we remembered that, only a short time before, the only available transportation was by ox or mule team, consuming an entire season to make the trip. After stage service was established, it required in the neighborhood of a month to travel from the Missouri River to the coast, and our travel, though slow, was unraveling new scenes and writing new lessons on the blackboards of our experiences.

From the car window we peered into the distance to get a glimpse of a remnant of the once great herds of buffalo that only a few months before had furnished meat for the construction crews of the Union Pacific Railroad through western Nebraska, and we watched the capering antelope with their white end toward us seeking shelter in the distance, or viewed with some suspicion groups of Sioux and other Indians, who from distant elevations watched our train pass as they sat straight as arrows on their ponies.

As we were pushed onto a siding at Laramie, Wyoming, to wait for a train, we could see from the car window an animal we took to be a wolf chained to a post. I persuaded my friend Johnny that we go and see it. We were told it was a coyote. It tugged nervously at the chain which fastened it to a post in front of a saloon. We could see through the open door the walls decorated with animal hides. Cautiously we stepped inside the door. Three or four men who occupied the room paid us very little attention, but I could see that the long-tailed linen dusters which we wore seemed to be a curiosity to them; and one of the men, wearing a six-shooter that hung swaggeringly over his hip, approached us and inquired if we were preachers. We told him that we were not. He seemed to doubt us and remarked that only preachers and sports wore that kind of coats in that country.

At this point two men alighted from a wagon and rather boisterously entered the saloon. One of them, seemingly a lively fellow, whom the bartender addressed as Tom, tossed a dollar on the bar, ordering drinks for himself and partner. As they were about to drink, the man who had interrupted us approached them and said: “Tom, it has been some time since you danced for us.” Tom retorted: “Yes, and (as he made a pass to draw his gun) it will be a d—d sight longer.” But the intruder beat him to it and exclaimed: “Lay off that gun and dance!” and as the bullet from the intruder’s gun entered the floor near Tom’s feet the dancing began. Much excited, I said to my friend Johnny: “Let us go before they make us preach,” and since I was as badly scared as Johnny, I was able to keep up with him as we raced for our train.

Later that evening I looked over Johnny’s shoulder to see him writing a letter to his mother explaining that he was sure the West was not going to agree with his health.

From this time on we stayed close to our train until we entered the Mormon territory of Utah, where from every sagebrush scampered a jackrabbit, juggling his hind feet as if in preparation for a real race.

We were reminded of Captain White’s song advising a side trip from the Mormon village of Ogden to Salt Lake City, the home of Brigham Young and his nineteen or more wives, but we traveled now over the Central Pacific Railroad, passing Promontory on the shore of the Great Salt Lake. Promontory was made famous in 1869 when the Golden Spike was driven there connecting the Union and Central Pacific railways.

On we went until we landed in Kelton, Utah, where we left the train to take the stage into Idaho. Kelton, at this time and for several years later, was a historical place situated on the north end of Great Salt Lake, a mere speck in the desert, consisting of some half a hundred houses built around the depot, and large commission warehouses for handling the freight for Idaho. Groups of blanket Indians loitered around the depot, curiously watching the incoming trains and passengers. Large ox and mule teams moved here and there, loaded for the interior, or preparing to load. Every other door was a saloon with gambling wide open.

A daily stage left Kelton for The Dalles, Oregon, passing through Idaho, which would furnish us our next experience; and as we balanced ourselves to conform to the rough swing of the Thurnabrac coach on our two-day stage trip, our minds drifted back to the homes and associates we had left. My mind was buoyant in expectation of new experiences, but poor Johnny had seen enough. I felt sorry for him and somewhat guilty for his state of mind, and tried to encourage him. It was the 8th of August, 1875, that we arrived at our destination, more than one hundred miles from a railroad at a junction of the Oregon Trail and stage road adjacent to the Snake River mines, the only settlement in south-eastern Snake River Valley Here Johnny procured employment with the stage company and I in a trader’s store.

Sixty days later, just when the mountains were putting on their fall coat of variegated colors with their high peaks capped in white, I bade Johnny goodbye as he happily climbed on the stage to return to his Iowa home. It made me homesick. I, too, had left a good home and associates, and as I turned my head to hide a tear, I mused: “Oh, why should I stay?”

Then I thought: “I love the mountains, the mountain streams, the western atmosphere, and the hospitable people with their western ways, the smoky odor of Indian-tanned buckskin, so prevalent around the camp fires, mingled with the sage-sweetened air, and the ever-present element of risk even to the preservation of life; and even the frequent solitude has its fascination.”

As I mused, the stage had disappeared in the east and Johnny was lost to me forever.

CHRISTMAS DINNER SIXTY YEARS AGO

IN THE EARLY FORTIES two young men whose homes were in Pennsylvania accepted employment with one of the many stage lines which were pushing their way into the West at that time. These two young men were the Trotter brothers, Charles and William. When they, in following their employment, reached Iowa, the younger of the two boys married my oldest sister. Accompanied by their families, they followed staging, which continually led them farther west, until along in the sixties when they reached the Missouri River and went into employment with the Overland Stage Company, a Ben Halliday line, running between Omaha, Nebraska, and the Pacific coast. These two men always held responsible positions with the stage company, usually serving as division agents.

The construction of the Central Pacific Railroad east from the Pacific coast, and the Union Pacific Railroad hurriedly pushing its way west from Omaha, Nebraska, shortened each day the overland stage road at both ends.

In 1868 the Trotter boys left the California line, coming into Idaho and taking employment on the stage line running from Fort Hall to Boise, a route which had been completed in 1864.

In 1869, when the two Pacific railroads were completed and a mail route was established from Kelton, Utah, to The Dalles, Oregon, the two Trotter boys moved on to that line, and, as they were getting along in years, and, with their families, wanted to settle down, they both took charge of eating stations. Charles Trotter, my brother-in-law, took the Rock Creek station, and William Trotter took the City of Rocks station, fifty miles east. Both of these stations sprang into prominence on account of the hospitality of the landlords and the appetizing meals served. My sister, Mrs. Trotter, from the year she was married, made annual trips back home, bringing with her the atmosphere of the West, and her graphic descriptions of frontier life made such an impression on my young mind that at the first opportunity (I made the opportunity), I came west, landing at Rock Creek station on the 8th day of August, 1875.

It was customary in those day for all emigrants, or tender-feet, to have the mountain fever immediately after arriving in this country, and as soon as I was aware of what was expected of me developed quite a severe case of so-called mountain fever, and for a couple of weeks I was certainly a sick kid. If I had not been so sick I might have been homesick, which would have been about as bad, but after some two weeks we got the fever broken, or it wore itself out, or I changed the thought, or something. At any rate I lost my fever; but not until it had burned up all my surplus flesh and more too, leaving me in a very weakened condition.

In the absence of a doctor (one could not be secured nearer than Boise) my friends prescribed sagebrush tea. I have always thought the early popularity of sagebrush was mostly on account of its plentifulness; but at any rate I drank at least enough to fill two wash boilers of strong sagebrush tea. This was to break my fever, and, as I said, the fever left me in a very weakened condition.

In a short time I began to mend and regain my strength, and soon found myself with a very great desire to eat food. I wanted to eat all the time and at Rock Creek station, where I was boarding, the stage arrivals made necessary the serving of four meals each day, and I ate at all of them. My friends became alarmed, feeling that I would overeat and have a relapse, and advised that I make a trip to the City of Rocks station and stay with Bill Trotter until I was able to go to work.

I found when I arrived at the City of Rocks that on account of the time of the stage arrivals they had five meals a day. Mr. Trotter undertook to tramp on my toes when he thought I had had enough to eat, but he soon gave it up, as I always had beaten him to it, and on each day I gained strength and flesh.

I was doing so well that Mr. Trotter persuaded me to stay with him and “run helper” over the summit. My duties would be to ride on an outrigger, or projecting seat on the sled opposite the driver, and at frequent intervals, which would be indicated by the driver, stick a willow into the snow as a guide to where the road was when we came back. My employment was not to begin until the snow came, which might be any time after November first. That would give me plenty of time to regain my strength.

I decided to stay. I liked City of Rocks station, built on the east side of the mountain among scattering pines on the headwaters of Raft River, and on the line of the old California emigrant road. The buildings were of logs and, as it was handy for material, they were built commodiously but with low ceilings. The sitting room, or barroom, was about thirty feet long east and west by some fourteen feet wide. The large fireplace in the west end, the dining room, kitchen, and three bedrooms were as commodious; but at any time except meal time or when I was out running over the mountains, I could be found in the barroom, watching the snow fall, hoping that the fall would be sufficient to put on a sled, or probably sitting by the open fireplace talking to Glove-Maker Jim, who sat tailor fashion on a table nearby working on some buckskin articles, as he would relate his experiences of fifty years ago when he was trapping with the John Grant Fur Company with headquarters at old Fort Hall. I don’t know what the glove-maker’s surname was; I only remember that he was called Jim, the Glove-Maker. He was an old friend of William Trotter, and was a man of about seventy years of age—a hale, hearty, tidy old man, ripe in the experiences of the West. My eagerness to listen was an incentive for him to talk, and I could always get a story from him about his Indian experience or his life as a trapper fifty years ago.

A great many Indians came to the City of Rocks at that time of year. Many came to gather pine nuts, and some came to sell their venison. I greatly enjoyed getting some of these Indians into the house and having Glove-Maker Jim talk to them. Jim spoke Indian and apparently was equally conversant with either Bannack, Shoshone, or Piute, all of whom came to the pine nut country. Usually Jim would translate these Indian conversations for my benefit, and the time passed swiftly and pleasantly at City of Rocks; and when the first of December was with us I had stored up more energy than it required to tramp out several four-horse stage outfits floundering in the snow.

You know those old stage horses that have had great experience don’t struggle in the deep snow, but when it gets too deep quietly lie down; then the helper gets among them and tramps the snow down solid, and when the driver speaks to them, they get up and move on. Usually the experienced snow horse will run through the snow route in the winter and will be removed to the low valleys in the summer; and when I learned that the company was moving its snow horses to the mountains I realized that my work was about to commence. I was pleased one afternoon when William Trotter told me to go to the creek and cut four bundles of willows about the size of my little finger and some eighteen inches long, leaving the bush on. I was to cut about one hundred in all, and he continued to tell me that when the stage went west on the next morning they would go by sled. I cut the willows and ...

Table of contents

- Title page

- TABLE OF CONTENTS

- DEDICATION

- AUTHOR’S PREFACE

- AUTHOR’S INTRODUCTION

- PART I-FALLING IN LOVE WITH IDAHO

- PART II-IDAHO SIX DECADES BACK

- EPILOGUE-TO IDAHO

- APPENDIX-SOUTH IDAHO’S NAMES

- REQUEST FROM THE PUBLISHER

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Six Decades Back by Charles Shirley Walgamott in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & American Civil War History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.