![]()

BOOK IV—TO THE STARS

![]()

XXXVI—THE DEVIL IS LET LOOSE

WHAT followed was the greatest campaign in American history, one of the greatest in any history, possessing for the military student the same passionate thrill of inspired performance as a Beethoven symphony for the musician or a da Vinci portrait for the painter. During the five months since Chattanooga both armies had become perfectly attuned instruments; the high commands were accurately balanced for the roles they assumed. Sherman’s fire was mitigated by the solidity of his lieutenant, Thomas; Joseph Johnston had replaced Bragg for the Confederacy, a wary defensive man, enlivened by the boldness of his helper, Hood. The prize was worthy the contestants; Atlanta was the great city of the Confederacy, the plexus of the railroads connecting Richmond with the deep South, the indispensable center of all its heavy industries, cannon and powder factories, rolling mills and depots of supply. The Union army had 98,000 men, the Confederate 71,000—exactly the odds which would permit the former to attack with even chances across the bastions of the Appalachian ridges.

Johnston thought they must attack with shouts and flashing cannon; “Cump” Sherman, he knew the man from old days at the Academy, a sanguine, liquid fellow with a bad nervous system, given to outbursts of temper, who would drive in like fury and tumble back as fast, leaving the way open for a powerful counterstroke. There was only one way he could come—straight down the railroad from Chattanooga. The Confederates spent the winter stretching breastworks thirteen feet thick across this line between the breakneck precipices around Dalton and gathering their forces for the blow. It was heavy work; Jefferson Davis, galled to the quick at being forced to dismiss his favorite, Bragg, haggled over every pound of beans, and Johnston had no art of conciliation to make things easier.

Sherman’s trouble was transport; only one line down to base at Ringgold and a hundred thousand unproductive mouths to feed, with the country naked as a senator’s skull. They ground up corncobs to make their bread till he appointed an energetic Colonel Anderson director of rails, sent him to Nashville to steal locomotives from the Northern lines and closed the supply road to civilian traffic. The population howled; the nabobs who were making a good thing out of contraband cotton turned the political thumbscrews on Lincoln, who begged Sherman to withdraw the order.

“The railroad cannot supply the army and the people, too, one of them must quit,” retorted the general. “I will not change the order and I beg of you to be satisfied that the clamor is humbug.” Two years ago this would have been cause for dismissal but now Lincoln merely used it to convince the politicians that he was unable to do anything with these rude warriors and they dried up, while Sherman stripped his army to the buff for work. One wagon to a regiment, no tents even for officers, no change of clothes, not even kitchen utensils. Three weeks out a Confederate cartel officer found the commanding general squatted by a roadside, coat unbuttoned, his face dark with a combined accumulation of red beard and black dirt, probing in a tomato can with a pocket knife for lumps of meat and carrot.

This program would not do for Thomas, however, who felt ill if there was a speck of dust on his boots and told an officer that the fate of an army might depend upon a buckle. He refused to eliminate his creature-comforts as flatly as Sherman to change the railroad order. The rest of them laughed at “Thomas’ circus” or “Tom town,” but the old man was the shield of the army, the boss round which Sherman could spin his arabesques of maneuver.

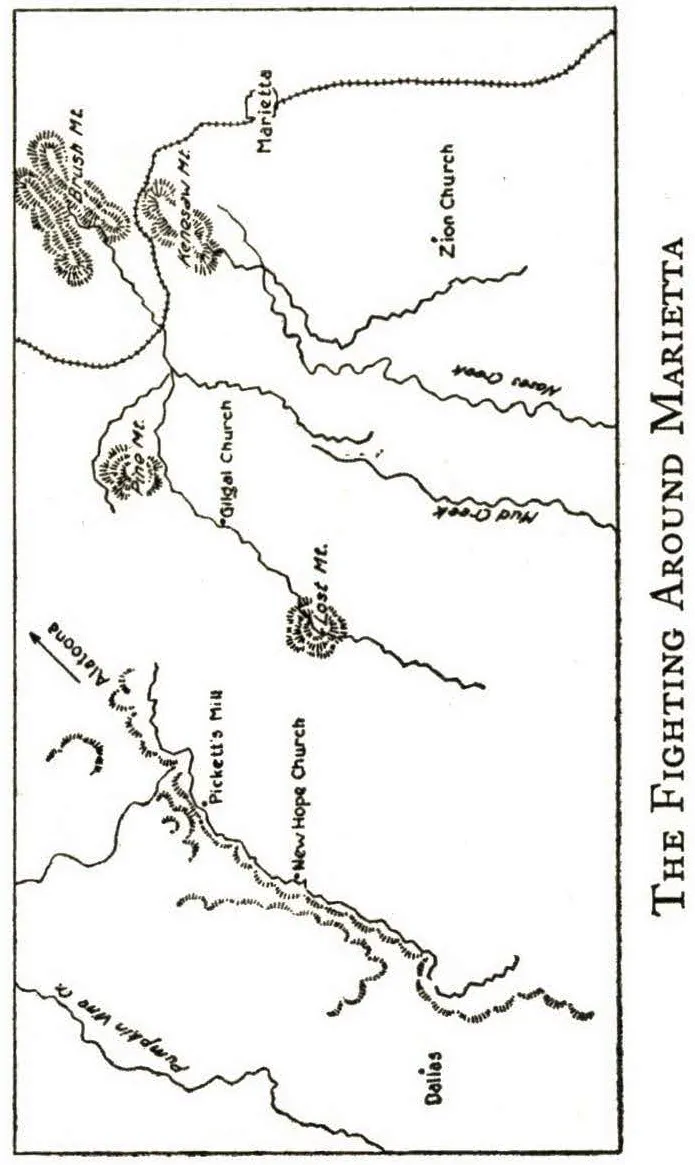

As on the first operation of the campaign. The army came down the roads to a stand before the buttress of Rocky Face Mountain with the Army of the Ohio (13,000) on the left under Schofield, a new man, a philosopher with a long beard, suspect as a dude and intellectual till one day the men saw him chewing tobacco—“He’s all right, boys, look how he handles that cud.” Thomas had three corps (Army of the Cumberland—61,000) in the center, McPherson two corps (Army of the Tennessee—24,000) on the right. Schofield tapped at the summits but between granite and gunnery made no headway; Thomas massed as though for assault and Johnston thought he had tempted his rash adversary. He was mistaken; the country was savage as Turkestan, without maps, but Thomas remembered having ridden through a narrow gorge, Snake Creek Gap, years before. It debouched on the banks of the Oostanaula near Resaca, behind the rebel flank and onto their railroad line. Sherman snapped at the plan his lieutenant drew; on the 9th May the Armies of the Cumberland and Ohio made a noisy pretense of attack that kept the Confederates within their lines at no sacrifice of life, while McPherson filed to the right through an awesome defile where the sun never reached bottom, into the broken ground around Resaca.

The rebels had a cavalry division in the town. They came out and annoyed McPherson, who took them for the precursors of a bigger force and intrenched in the gut of the pass. Sherman’s messenger galloped through mud and rain to urge him on, but the news rode faster to Johnston down the electric telegraph, and he had two army corps on hand by train before McPherson nerved himself to try assault. Next day the Union pressure on the Dalton lines relaxed; Johnston thought Sherman had followed the Army of the Tennessee down to Resaca, and made an attack with the design of breaking down the Federal rearguard and cutting Sherman’s lifeline railroad. Mistake again; Sherman had sent only a corps to McPherson. The attack fell on Thomas and like most attacks on the Rock of Chickamauga, broke down with loss. Johnston dared no longer stay in his fortress with McPherson hammering at his rear, and that night left for Resaca. Sherman wins this round, the Dalton lines are flanked—but he must tell McPherson, “Well, you have missed the greatest opportunity of your life.”

A creek, Camp Creek, covered the west front of Resaca, with high hills behind it. Johnston had his three corps in a semicircle of fortifications from south to north, Polk, Hardee and Hood. Sherman came in against it along a somewhat pinched front, with Schofield swinging wide to the north. Hood discovered that Thomas’ left flank was bare and launched a stirring charge against Howard’s Corps, which held it. He got not far; Sherman had discovered the weakness and threw Hooker against Hood’s flank as the rebel went in. Hood was badly mauled before he could get out, but Johnston reinforced him from Hardee and ordered a stroke on Schofield for daybreak.

Before it took place there was trouble at the other end of the line, where Polk had intrenched a commanding height on the west side of Camp Creek mouth. Osterhaus, “Sow-belly Osterhaus” of Logan’s Corps of McPherson, stormed a bridge and penetrated Polk’s line; from the height he gained he smothered the west hill trenches under a cross-fire and won them, too. Logan got his artillery onto the eminence, and as twilight came down, shot out the railroad bridge, Johnston’s only line of retreat, and began to rain shells into the streets of the town. Simultaneously, McPherson got a corps, Dodge’s, across the Oostanaula lower down, and came swinging up river with a storm cloud of cavalry round him. Johnston canceled Hood’s attack order and beat a hurried retreat on a pontoon bridge; next morning Sherman was in Resaca with the second round won.

Shift scenes for the next act; the mountain passes are passed, here we are in the rolling prairie between the Oostanaula and the Etowah, with Sherman getting his food down a long neck of railway line as sensitive as a giraffe’s, an Johnston sitting right on his base, drawing in continual reinforcements. Rebel scouts said Sherman was moving in close column, concentrated for battle. Johnston laid a deadly ambush at Adairsville, with both flanks forward on hills, concealed, center intrenched across the intervening valley, to catch Sherman’s column in a narrow funnel and crowd it to death. On the 16th, afternoon, Howard’s Corps of Thomas came up out of a stream the men had crossed by wading naked with packs held overhead, to find the rearguards stiffening; the air smelled of battle. Howard spread skirmishers and punched through the screen before him, then formed line with orders “attack at dawn.”

Johnston’s midnight orders were the same, but at two in the morning a wild-eyed aide roused him with the news that Garrard’s Union light horse had ridden into Rome the previous noon, followed by a division of infantry, the vanguard of McPherson’s whole army, which now lay outside and behind his left wing, ready to strike. Half an hour later came another Job’s messenger with tidings that Schofield had worked round the Confederate right flank. Instead of trapper Johnston was trapped; Sherman had capped his funnel with a bell of which Thomas was the clapper. He might hurt Thomas but certain annihilation was coming from the flanks if he stopped to do it. The men were gotten out of their tents in the cold dawn hours for a comfortless rapid retreat past hummocks of burning stores.

The old horse could still prance, however; Johnston sent only Hardee down the normal road to Kingston, himself taking Polk and Hood cross-country to Cassville. Sherman, as he expected, followed Hardee with Thomas and McPherson; only Schofield spread toward Cassville. The rebels tore up the railroad in retreat, twisted the rails, burned the ties and blew out the bridges; that would detain the gross of the Union army; Polk and Hood were to turn and demolish Schofield. Hardly had the rebels got into position, however, when their astonished ears caught the “Fweet-weet” of a locomotive whistle and Hardee came tumbling in on the main body, with the horizon from west to east behind him a-shimmer with Union bayonets. Sherman’s railroaders had actually rebuilt that line as fast as the troops marched, and Thomas had driven Hardee remorselessly before him, no chance for a stand. “That man Sherman,” said a disgusted Georgian, “will never go to hell. He’ll outflank the devil and get past Peter and all the heavenly hosts.” Retreat again; this time across the Etowah, where it runs deep and swift through a rocky gorge north of Allatoona, and a passage may not be forced.

Sherman did not try to force a passage; the detachments he made for rail guards had brought down his numbers to nearly equal Johnston’s, and though General Blair was coming from the west with a new corps, 10,000 strong, he had to be careful. He gave Blair a rendezvous at Eubarbee, the engineers threw a bridge at that point, and the army, with twenty days’ rations for a move away from its supports, crossed the Etowah into a new kind of country—a tangle of loblolly pine thicket so dense one cannot see twenty feet in any direction, interspersed with quicksand pools and high bosses of mountain which would be called mesas farther west. The direction was Dallas; from that point the army could cut in behind the Allatoona defile at Ackworth and get back to the railroad line.

Division Geary of Hooker’s Corps struck rebel outposts near Dallas on the evening of May 25, and there was fighting. Hooker found the Confederates intrenched on hills behind Pumpkin Vine Creek, but kept feeding his divisions in on the left as fast as they came up, and near New Hope Church delivered an assault with all his old spirit. Howard heard the tumult and gathering all Schofield’s men (who were on the road with him), rushed through the dark of a gathering night to fall on at Hooker’s left, near Pickett’s Mill. A storm came up; thunder, lightning and artillery fire cracked across the night as the armies locked in fierce grapple, but at six in the morning, with Palmer’s Corps of Thomas coming up behind Hooker and the Army of the Tennessee falling in on his right, they had to give over with nothing gained and many men lost.

The next day there was continuous hot skirmisher fire along the line; officers dared not appear on horseback, the sharpshooters picked them off. Men called the place “the Hell Hole.” On the third day Howard tried the Confederate right again, thought he had outflanked it and went in full steam, but only fell into a re-entrant angle of Hood’s line and was severely punished. Sherman’s line was a mess, with divisions, brigades and regiments everywhere as they had come in down the back roads and army commanders did not know the location of half their men. The Union leader adroitly used the fact to build up a new movement, by picking the pieces of Schofield’s Army of the Ohio out of line and filing them left, behind the rest for a wide flanking sweep toward Allatoona. Johnston spotted signs of activity opposite. Sherman had got this far by perpetually sweeping around his left; he thought the Federals would try to do the same thing again, and ploying Hardee’s Corps into heavy columns, tried to hurl it through McPherson’s center, the hinge of the movement as he imagined it. McPherson received them with a concave line and a centered artillery fire that brought men down by hundreds; meanwhile Schofield and the cavalry worked around behind Johnston’s right flank, captured Allatoona and the river-crossings and compromised the whole Confederate line.

As usual the general advance found Johnston vanished into the pinelands southward. Sherman held Schofield fast in his new position while he slid Thomas and McPherson around behind him to base on the railroad line, then felt forward; General Hazen noted that the men in his brigade were letting their hair grow “till they looked like prophets.” Down in Atlanta Braxton Bragg had arrived as the personal representative of Jefferson Davis. He surveyed the operations of his successor (and enemy) Johnston with a jaundiced eye and reported to the President that the man was destroying the morale of the rebel army by constant retreat under heavy losses. Joseph E. Brown, the truculent and not too intelligent governor of Georgia, threatened General Johnston with civil arrest if he persisted in his obnoxious habit of interrupting commercial railroad traffic for his supply trains. And on the 5th June Sherman’s vanguard made contact with the new Confederate position.

It was the usual thing; double revetted trenches with slashed timber and chevaux-de-frise—frizzy horses—out in front, stretching from the mesa of Lost Mountain to that of Brush Mountain with Pine Mountain making a salient in the center. The lines covered every point of attack; they were prodigious—too prodigious, declared Sherman, riding along to inspect them from afar, at least ten miles overlong for such numbers as Johnston had, there must be a weak spot somewhere. He was opposite Pine Mountain as he spoke; at that moment his horse shied to the kick of a Minie ball and he looked up to see a party of rebel officers on an outcrop looking down. “Give them a shot,” he called to a battery nearby. The third shell fell on the group and slew the Confederate bishop-general, Polk. “Blizzards” Loring, who once held Grant off on the Yazoo, got his corps.

The steady snap of skirmisher fire rose crescendo as divisions all along the line pecked to find the soft spot; day and night they tapped away. The spring rains had come; the streams were up and the roads quagmires; out on the flanks life was frugal for the wagons with supplies could not get through. It prohibited the flanking move Sherman would have made, but on the 15th Thomas seeped men into the interstices of the Confederate line caused by rough ground around the foot of Pine Mountain and pinched out that salient. Johnston drew men from his right to take up the shock and held the new line b...

![Ordeal By Fire: An Informal History Of The Civil War [Illustrated Edition]](https://img.perlego.com/book-covers/3018828/9781786257789_300_450.webp)