- 176 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

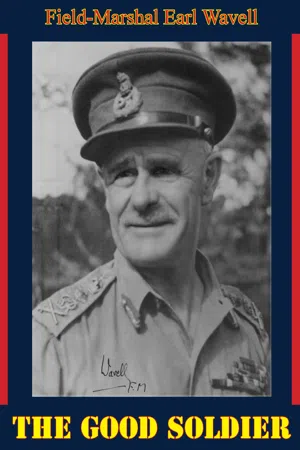

The Good Soldier

About this book

The Good Soldier contains the distilled wisdom of Field Marshal Wavell, collected from his numerous articles and speeches.

"Practically all the articles collected here were written between the two Great Wars, between 1926 and 1938; a few were written during the late war. Nearly all have been previously published, in newspapers or military journals. Whether they are worth collection and republication I must leave readers to judge. Inoculation with the deadly virus of war does not seem to confer immunity on any people or on the world as a whole for more than a very limited period. There must still be soldiers, and I fear there will still be wars in spite of UNO and ATOM. So long as war has to be studied there may be something of value in these notes of one who has studied war for close on fifty years. That is my only excuse for re-enlisting these old soldiers of my pen.

Some of them may be thought old-fashioned and out of date, with little more to tell the modern student of war than would a visit to the pensioners of Chelsea Hospital. But passing down their ranks and looking them over with, I admit, an indulgent eye, I still believe that there may be something in each of these veterans, or at least in some of them, to induce thought and perhaps to sow the germ of a fresh idea. If I can claim to any merit as a soldier, it is that I have always tried to keep my mind receptive to fresh ideas, and that I have striven to present these ideas in as simple and practical a form as possible—in battle dress rather than in review order. If these old soldiers of mine can in any way help a young soldier to learn his trade—the training and handling of men in circumstances of great complexity and difficulty—they will not have come back from the Reserve in vain."—Author's Preface, 1946

"Practically all the articles collected here were written between the two Great Wars, between 1926 and 1938; a few were written during the late war. Nearly all have been previously published, in newspapers or military journals. Whether they are worth collection and republication I must leave readers to judge. Inoculation with the deadly virus of war does not seem to confer immunity on any people or on the world as a whole for more than a very limited period. There must still be soldiers, and I fear there will still be wars in spite of UNO and ATOM. So long as war has to be studied there may be something of value in these notes of one who has studied war for close on fifty years. That is my only excuse for re-enlisting these old soldiers of my pen.

Some of them may be thought old-fashioned and out of date, with little more to tell the modern student of war than would a visit to the pensioners of Chelsea Hospital. But passing down their ranks and looking them over with, I admit, an indulgent eye, I still believe that there may be something in each of these veterans, or at least in some of them, to induce thought and perhaps to sow the germ of a fresh idea. If I can claim to any merit as a soldier, it is that I have always tried to keep my mind receptive to fresh ideas, and that I have striven to present these ideas in as simple and practical a form as possible—in battle dress rather than in review order. If these old soldiers of mine can in any way help a young soldier to learn his trade—the training and handling of men in circumstances of great complexity and difficulty—they will not have come back from the Reserve in vain."—Author's Preface, 1946

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

PART I—GOOD SOLDIERS

“‘Generals and Generalship’ were three lectures delivered at Trinity College, Cambridge, in 1939, shortly before the outbreak of the late war; the two articles on Military Genius were written in 1942, when I was Commander-in-Chief in India; ‘The Good Soldier’ was written in 1945. They may, I suppose, be taken to represent my mature judgment on soldiers and soldiering, after more than fifty years of it.”—W.

GENERALS AND GENERALSHIP

I. THE GOOD GENERAL

WHEN you did me the honour to ask me to deliver this series of lectures I chose, instead of a campaign or a period of history, as I believe has been customary, to inflict upon you some general observations on generals and generalship. I felt that certain points which I wished to put before you with regard to the study of military history could thus be better illustrated than in the relation of some particular campaign. Comparatively few of you are perhaps likely to become generals; but many of you are likely to suffer, perhaps even to triumph, under generals; and all of you are likely to have opportunity to criticise generals. I should like your criticism to be as well informed as possible. Generalship, and especially British generalship, has had a bad Press since the late war (1914-18). I am not proposing to deliver to you an apologia for generals, but to explain the qualities necessary for a general and the conditions in which he has to exercise his calling.

While I was trying to define to myself the essential qualifications of a higher commander I looked back in history to see how these qualifications had been defined in the past. I read a number of expositions, by various writers, of the virtues, military or otherwise, that were considered necessary for a general. I found only one that seemed to me to go to the real root of the matter; it is attributed to a wise man named Socrates. It reads as follows:—

“The general must know how to get his men their rations and every other kind of stores needed for war. He must have imagination to originate plans, practical sense and energy to carry them through. He must be observant, untiring, shrewd; kindly and cruel; simple and crafty; a watchman and a robber; lavish and miserly; generous and stingy; rash and conservative. All these and many other qualities, natural and acquired, he must have. He should also, as a matter of course, know his tactics; for a disorderly mob is no more an army than a heap of building materials is a house.”

Now the first point that attracts me about that definition is the order in which it is arranged. It begins with the matter of administration, which is the real crux of generalship, to my mind; and places tactics, the handling of troops in battle, at the end of his qualifications instead of at the beginning, where most people place it. Also it insists on practical sense and energy as two of the most important qualifications; while the list of the many and contrasted qualities that a general must have rightly gives an impression of the great field of activity that generalship covers and the variety of the situations with which it has to deal, and the need for adaptability in the make-up of a general.

But even this definition of Socrates does not to my mind emphasise sufficiently what I hold to be the first essential of a general, the quality of robustness, the ability to stand the shocks of war. Probably this factor did not apply so much in Socrates’ time. People did not then suffer from what is now elegantly known as “the jitters” I can perhaps best explain what I mean by robustness by a physical illustration. I remember long ago, when I was a very young officer, being told by a mountain gunner friend that whenever in the old days a new design of mountain gun was submitted to the Artillery Committee that august body had it taken to the top of a tower, some hundred feet high, and thence dropped on to the ground below. If it was still capable of functioning it was given further trial; if not, it was rejected as flimsy. The committee reasoned that mules and mountain guns might easily fall down the hillside and must be made capable of surviving so trivial a misadventure. On similar grounds rifles and automatic weapons submitted to the Small-Arms Committee are, I believe, buried in mud for 48 hours or so before being tested for their rapid firing qualities. The necessity for such a test was very aptly illustrated in the late war, when the original Canadian contingent arrived in France armed with the Ross rifle, a weapon which had shown its superior qualities in target shooting at the Bisley ranges in peace. In the mud of the trenches it was found to jam after a very few rounds; and after a short experience of the weapon under active-service conditions the Canadian soldier refused to have anything to do with it and insisted on being armed with the British rifle.

Now the mind of the general in war is buried, not merely for 48 hours but for days and weeks, in the mud and sand of unreliable information and uncertain factors, and may at any time receive, from an unsuspected move of the enemy, an unforeseen accident, or a treacherous turn in the weather, a bump equivalent to a drop of at least a hundred feet on to something hard. Delicate mechanism is of little use in war; and this applies to the mind of the commander as well as to his body; to the spirit of an army as well as to the weapons and instruments with which it is equipped. All material of war, including the general, must have a certain solidity, a high margin over the normal breaking strain. It is often said that British war material is unnecessarily solid; and the same possibly is apt to be true of their generals. But we are certainly right to leave a good margin.

It is sometimes argued whether war is an art or science. I noted that in the invitation to me to deliver these lectures I was to choose some branch of the “science” of war. Perhaps had I been lecturing at a rival university it might have been termed the “art” of war. I know of no branch of art or science, however, in which rivals are at liberty to throw stones at the artist or scientist, to steal his tools and to destroy his materials, while he is working, always against time, on his picture or statue or experiment. Under such conditions how many of the great masterpieces of art or discoveries of science would have been produced? No, the civil comparison to war must be that of a game, a very rough and dirty game, for which a robust body and mind are essential. The general is dealing with men’s lives, and must have a certain mental robustness to stand the strain of this responsibility. How great that strain is you may judge by the sudden deaths of many of the commanders of the late war. When you read military history take note of the failures due to lack of this quality of robustness.

I propose to say a few words about the physical attributes of a general: courage, health, and youth. Personal appearance we need not worry about: an imposing presence can be a most useful asset; but good generals, as they say of good race-horses, “run in all shapes”. Physical courage is not so essential a factor in reaching high rank as it was in the old days of close-range fighting, but it still is of very considerable importance today in determining the degree of risk a commander will take to see for himself what is going on; and in mechanised warfare we may again see the general leading his troops almost in the front of the fighting, or possibly reconnoitring and commanding from the air.

As an example of the extent to which generals came under fire in the old days you may like to know that at Marlborough’s assault on the Schellenberg during the Blenheim campaign six lieutenant-generals were killed and five wounded in the Allied army, while the 1500 British casualties at the action included four major-generals and 28 brigadiers or lieutenant-colonels. There is a good story told of one of Napoleon’s marshals, Lefebvre, the gallant old soldier who became Duke of Danzig. A civilian friend was once envying him his house and decorations and other awards. At last the old marshal got tired of it and said to him: “Well, if you want all these things come out into my garden and let me have 10 shots at you at 40 paces. If you survive I will hand over to you my house and everything in it.” His friend, perhaps naturally, objected. “All right,” said the old marshal, “but remember that I had several hundred shots fired at me at that range before I got all these things.”

Courage, physical and moral, a general undoubtedly must have. Voltaire praises in Marlborough “that calm courage in the midst of tumult, that serenity of soul in danger, which is the greatest gift of nature for command”. A later military writer, who had no great admiration for Joffre, was compelled to admit that his stolid calm and obstinate determination in the darkest days of the retreat had an influence which offset many of the grave strategical blunders which he committed. Health in a general is, of course, most important, but it is a relative quality only. We would all of us, I imagine, sooner have Napoleon sick on our side than many of his opponents whole. A great spirit can rule in a frail body, as Wolfe and others have shown us. Marlborough during his great campaigns would have been ploughed by most modern medical boards.

Next comes the vexed question of age. One of the ancient Roman poets has pointed out the scandal of old men at war and old men in love. But at exactly what age a general ceases to be dangerous to the enemy and a Don Juan to the other sex is not easy to determine. Hannibal, Alexander, Napoleon, Wellington, Wolfe, and others may be quoted as proof that the highest prizes of war are for the young men. On the other hand, Julius Caesar and Cromwell began their serious soldiering when well over the age of 40; Marlborough was 61 at the time of his most admired manœuvre, when he forced the Ne Plus Ultra lines; Turenne’s last campaign at the age of 63 is said to have been his boldest and best. Moltke, the most competent of the moderns, made his name at the age of 66 and confirmed his reputation at 70. Roberts was 67 when he went out to South Africa after our first disastrous defeats, and restored the situation by surrounding the Boer Army at Paardeberg and capturing Bloemfontein and Pretoria. Foch at 67 still possessed energy and vitality and great originality. We must remember, in making comparisons with the past, that men develop later nowadays; for instance, Wellington, Wolfe, Moore, Craufurd were all commissioned at about the age of 15, and some of them saw service soon after joining. It is impossible really to give exact values to the fire and boldness of youth as against the judgment and experience of riper years; if the mature mind still has the capacity to conceive and to absorb new ideas, to withstand unexpected shocks, and to put into execution bold and unorthodox designs, its superior knowledge and judgment will give the advantage over youth. At the same time there is no doubt that a good young general will usually beat a good old one; and the recent lowering of age of our generals is undoubtedly a step in the right direction, even if it may sometimes lose us prematurely a good commander.

I don’t think I need expatiate for long on the moral qualities of a leader. No amount of study or learning will make a man a leader unless he has the natural qualities of one. The qualities of a leader are well known to you and I shall deal with them further in my second lecture. Here I will mention only the barest essentials.

He must have “character”, which simply means that he knows what he wants and has the courage and determination to get it. He should have a genuine interest in, and a real knowledge of, humanity, the raw material of his trade; and, most vital of all, he must have what we call the fighting spirit, the will to win. You all know and recognise it in sport, the man who plays his best when things are going badly, who has the power to come back at you when apparently beaten, and who refuses to acknowledge defeat. There is one other moral quality I would stress as the mark of the really great commander as distinguished from the ordinary general. He must have a spirit of adventure, a touch of the gambler in him. As Napoleon said: “If the art of war consisted merely in not taking risks glory would be at the mercy of very mediocre talent”. Napoleon always asked if a general was “lucky”. What he really meant was, “Is he bold?” A bold general may be lucky, but no general can be lucky unless he is bold. The general who allows himself to be bound and hampered by regulations is unlikely to win a battle. As a “cautionary tale” of what may happen to a commander who allows himself to be bound by the letter of regulations, I will take an example from naval history.

About 175 years ago a conscientious but somewhat limited admiral was pacing his quarter-deck in earnest consultation with his flag captain, while an enemy fleet lay close at hand at the mercy of his attack. The point on which the admiral was so earnestly engaged was in making certain that the dispositions he proposed to adopt in his attack on the enemy were strictly in conformity with some very long-winded and complicated instructions lately laid down by the Lords of the Admiralty. His flag captain was able to assure the admiral that what he proposed to do was strictly in accordance with the regulations; but in the meantime the enemy fleet made good its escape, and the admiral on his return home was tried by Court-martial and shot, pour encourager les autres. If it encouraged them to disregard regulations at need, the ill-fated Admiral Byng did not die in vain. It is in peace that regulations and routine become important and that the qualities of boldness and originality are cramped. It is interesting to note how little of normal peace soldiering many of our best generals had—Cromwell, Marlborough, Wellington, and his lieutenants, Graham, Hill, Craufurd.

So far we have dealt with the general’s physical and moral make-up. Now for his mental qualities. The most important is what the French call le sens du praticable, and we call common sense, knowledge of what is and what is not possible. It must be based on a really sound knowledge of the “mechanism of war”, i.e. topography, movement, and supply. These are the real foundations of military knowledge, not strategy and tactics as most people think. It is the lack of this knowledge of the principles and practice of military movement and administration—the “logistics” of war, some people call it—which puts what we call amateur strategists wrong, not the principles of strategy themselves, which can be apprehended in a very short time by any reasonable intelligence. May I give you a homely illustration? A man planning a holiday may decide for himself, or may be advised, that Egypt is the place to go to. That is easy; but then he has to calculate the time it will take him to get there and the cost of the trip, and compare it with the length of his holiday and of his purse. And it is that which is the difficult part of the job. As a political example: there are the unemployed, there is a job of work. Anyone can see it would be a good thing to put the unemployed to do the job. But to overcome the practical difficulties of movement, housing, finance, etc., is a very difficult thing.

Unfortunately, in most military books strategy and tactics are emphasised at the expense of the administrative factors. For instance, there are ten military students who can tell you how Blenheim was won for one who has any knowledge at all of the administrative preparations that made the march to Blenheim possible. There were months of administrative planning to make Allenby’s manœuvre at the third battle of Gaza practicable. Again, Marlborough’s most admired stratagem, the forcing of the Ne Plus Ultra lines in 1711, was one that a child could have thought of but that probably no other general could have executed. Roberts’ manœuvre before Paardeberg in 1900, Allenby’s at Gaza-Beersheba in 1917, were both variations of the same very simple theme as Marlborough used in 1711; but again it required very intelligent and careful preparation to execute it. I should like you always to bear in mind when you study military history or military events the importance of this administrative factor, because it is where most critics and many generals go wrong.

In conclusion, I wonder if you realise what a very complicated business this modern soldiering is. A commander today has now to learn to handle air forces, armoured mechanical vehicles, anti-aircraft artillery; he has to consider the use of gas and smoke, offensively and defensively; to know enough of wireless to make proper use of it for communication; to understand something of the art of camouflage, of the business of propaganda; to keep himself up to date in the developments of military engineering: all this in addition to the more normal requirements of his trade. On the battlefield, of course, conditions are completely different. Marlborough at Blenheim, after placing the batteries himself and riding along his whole front, lunches on the battlefield under cannon fire waiting for his colleague Eugène on the right flank, four miles away, a great distance for those days. Napoleon at Austerlitz can with his own eyes see the enemy expose himself hopelessly and irretrievably to the prepared counter-str...

Table of contents

- Title page

- TABLE OF CONTENTS

- PREFACE

- PART I-GOOD SOLDIERS

- PART II-TWO UNORTHODOX SOLDIERS

- PART III-IN PRAISE OF INFANTRY

- PART IV-TRAINING FOR WAR

- PART V-ORGANISATION OF ARMIES

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access The Good Soldier by Field-Marshal Earl Wavell in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & European History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.