- 204 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

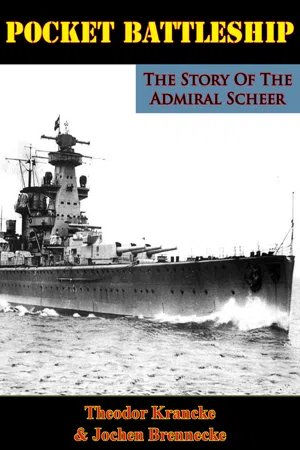

Pocket Battleship: The Story Of The Admiral Scheer

About this book

The exciting account of the famous German battle cruiser which sank 152,000 tons of Allied shipping.

A LUCKY SHIP

The Germans called her their "lucky ship"—the heavily gunned, heavily armoured Admiral Scheer, sister ship of the ill-fated Graf Spee and the Deutschland. With and operational range of 19,000 miles, she quickly became a nightmare to the British Admiralty.

This is the dramatic story of one of the most successful fighting ships in the German Navy, told by two German officers: who commanded her. It also contains the thrilling account, as seen for the first time through German eyes, of the sinking of the Jervis Bay. This lightly armed auxiliary cruiser went down with all guns blazing in a daring and gallant attempt to protect her convoy from the mighty dreadnought.

"This story of a great raider, searching out enemy; commerce under the nose of powerful naval forces is always enthralling."—N. Y. Herald Tribune

"A first-rate account of warfare at sea."—Cleveland Plain Deale

"Gives an unusual glimpse into what the Nazi side of the war was like."—Chicago Tribune

A LUCKY SHIP

The Germans called her their "lucky ship"—the heavily gunned, heavily armoured Admiral Scheer, sister ship of the ill-fated Graf Spee and the Deutschland. With and operational range of 19,000 miles, she quickly became a nightmare to the British Admiralty.

This is the dramatic story of one of the most successful fighting ships in the German Navy, told by two German officers: who commanded her. It also contains the thrilling account, as seen for the first time through German eyes, of the sinking of the Jervis Bay. This lightly armed auxiliary cruiser went down with all guns blazing in a daring and gallant attempt to protect her convoy from the mighty dreadnought.

"This story of a great raider, searching out enemy; commerce under the nose of powerful naval forces is always enthralling."—N. Y. Herald Tribune

"A first-rate account of warfare at sea."—Cleveland Plain Deale

"Gives an unusual glimpse into what the Nazi side of the war was like."—Chicago Tribune

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Pocket Battleship: The Story Of The Admiral Scheer by Theodor Krancke,Jochen Brennecke in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & European History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

PART ONE—ALONE IN THE NORTH ATLANTIC

1. The Admiral Scheer Slips Out

“BLASTED Pocket-Battleship!”

German naval anti-aircraft gunners heard the words as they dragged the wounded pilot of a British bomber out of the wreckage of his machine.

“What did you say?” asked one of them who could speak English. Half propped up on the ground and surrounded by Germans, who were doing their best to make him comfortable, the pilot pushed the hair out of his eyes with his undamaged hand and made no answer. He knew already that he had said too much and the thin line of the white lips in his contorted face was sufficient indication that he intended to say no more.

Nor did he. But he had said enough. Naval Command Group North in Wilhelmshaven now knew what it had previously only guessed: the efforts of the R.A.F. were directed against the heavy cruiser Admiral Scheer, a sister ship to the Graf Spee and the Lützow, powerful units of the small German Navy which were causing a certain amount of misgivings in the Admiralty in Whitehall, and even more amongst the captains of the British Merchant Marine whose job it was to keep the British Isles supplied during the war.

The Graf Spee scuttled herself in Montevideo Harbour after an engagement on December 13 with the British cruisers Ajax, Achilles and Exeter. The Lützow, renamed the Deutschland, managed to return home safely from her operations despite everything the British Navy could do.

The so-called pocket-battleship, Admiral Scheer, was known to be lying in Wilhelmshaven undergoing an entire refit, and the British Admiralty strongly suspected that when she was ready she would be sent out into the North Atlantic as a commerce raider. In consequence instructions were issued to bomb the naval shipyards at Wilhelmshaven as heavily as possible in the hope of damaging the Scheer before she could be got ready and sent out. The raids on Wilhelmshaven were persisted in and the British losses rose steadily, but they would gladly have accepted them all if only the Admiral Scheer, “the blasted pocket-battleship” of the wounded pilot, could have been destroyed, or even seriously damaged. In fact the bombers did not score a single hit on their target although the Scheer was in dock from February to July, 1940, for widespread alterations, and even after that she lay alongside the North Mole of Entrance III for quite a time to have her guns adjusted.

The Scheer had an operational range of something like 19,000 miles and the British Admiralty was quite right when it suspected that the strategic plans of the German Naval Operations Command included her use as a commerce raider in the Atlantic. But something they did not know at the Admiralty and what their air reconnaissance had not been able to tell them, was that the “pocket-battleship” had been given a completely new silhouette quite different from the characteristic cruiser type. The previous typical fighting mast, recognizable easily at a great distance, had been so thoroughly altered that is now looked more like the fighting masts of battle-cruisers like the Scharnhorst and the Gneisenau, or of heavy cruisers like the Hipper and the Prinz Eugen.

Captain Theodor Krancke, the commander of the Admiral Scheer, hoisted his flag on November 1, 1939, soon after the outbreak of war. The first few months of his command were uneventful and the ship saw no action. The crew had no chance of getting to know the new captain properly, but they did know that before coming to them he had been O.C. of the Naval Academy and that made them suspect wryly that he was probably more of a naval theoretician and a scientist than a real fighting seaman. Under the previous captain, Hans-Heinrich Wurmbach, the Scheer anti-aircraft gunners had shot down the first British bomber to be bagged either by the Fleet or the coastal batteries. The anti-aircraft guns of other ships had fired at the attacking British bombers too, but the Scheer had booked the first success. Under Wurmbach the Scheer had obviously been lucky. Would she be as lucky under the new captain? The fact that he smoked strong Brazils was taken to be a good sign by the ship psychologists.

When the Scheer went into dry dock her commander was ordered to Berlin where the Supreme Command entrusted him with the operational preparations for the campaign at sea against Norway. The crew had no inkling of what had taken their commander to Berlin in the first place or of what kept him there so long. But in any case, they had enough urgent matters of their own to attend to. Half the men on board were new ratings who had come on board to replace older and experienced men who had been posted to various training schools, a measure of reorganization made necessary by the swift enlargement of the fleet personnel and in particular of the submarine arm. But in view of what he knew about the secret instructions to be put into action with the Scheer later on, the presence of so many new and inexperienced men on board seemed a big risk to her commander and filled him with misgivings.

After the end of the Norwegian campaign and the occupation of the country, Captain Krancke remained Chief of Staff to Admiral Böhm in Norway until June, 1940, when he returned to Wilhelmshaven to take command of the Admiral Scheer once again. In the meantime she had completed her structural alterations and her refit and could leave dock. It was in this period that the nightly raids by British bombers took place.

The vessel then made the usual trial cruises in the Baltic and after that began intensive work to train the new men who were now on board and make them part and parcel of a homogenous crew. As many of them had never felt a ship’s planks under their feet before it was no easy task. However, now that the Scheer was out of dry dock she had to be made ready to go into action as quickly as possible and so the training went on day after day and often in the night as well. Artillery, anti-aircraft and torpedo firing practice took place in the Baltic between Swinemünde and the Danzig Bight under circumstances which were made as realistic as possible with supposed control and other breakdowns, supposed direct hits and so on. The crew were to be trained to meet every possible emergency, whether in the book or not. In addition there were all the innumerable technical gadgets to be mastered, new machinery to be run in, wireless and radar apparatus to be tried out. A second wireless room had been set up in the former midshipmen’s mess and the job of the W/T men there was solely to monitor-foreign broadcasts and keep a constant tab on a great number of wave-lengths. In addition there was highly secret radar apparatus to be tried out.

Something of the sort had been offered to the Imperial Navy as early as 1912, but in view of the inadequate development of wireless technique in those days the device had not been taken seriously and it was not until the ‘thirties that Germany began to experiment with the idea again, first using centimetre wave-lengths. The results on these short wave-lengths were disappointing, but then much better and more promising results were obtained with decimetre wave-lengths. Ultimately a radar instrument known as the D.T. apparatus, operating between 80-and 150-cm wave-lengths was developed and it was also adopted both by the Luftwaffe and the anti-aircraft batteries. The secrecy with which this early radar apparatus was surrounded was so close that only men actually engaged on its operation were allowed to enter the radar cabin, and they were specially sworn to secrecy.

But there were radar developments in the enemy’s camp too. Starting on metre wave-lengths, they finally concentrated on very short wave-lengths of around 9 cm These shorter wave-lengths gave quicker and more accurate reception and provided a clearer image on the radar screens. In addition, the short-wave apparatus was lighter and handier, so that little ships and ultimately even planes could be equipped with it, whereas the weight and size of the apparatus adopted by the German Navy made it impossible for anything smaller than a destroyer to be equipped with it.

In the second phase of the war the enemy’s radar apparatus outstripped German developments, gave a greater range, and provided clearer and more accurate indications. However, the first radar apparatus installed in British ships did not make its appearance until the spring of 1941, and even then only on board a few of the cruisers, so that in the first phase of the war at sea the German Navy enjoyed a big radar advantage.

More and more men were climbing up the gangways of the Scheer now and dumping their sea-sacks on her decks. Gradually it became something of a mystery where they were all to be put and what the authorities intended to do with them in any case. The peacetime complement of the Scheer was 1,100 men, but by this time there were already 1,300 on board, including a number of reservists from the mercantile marine who were wondering what they were doing on board a heavy cruiser.

The first question a seaman posted to a new ship always asks is: “What’s the captain like?” The older hands on board were able to answer that one now: “All right.” And those who had been on board longest were able to tell them why. “None of the others ever took us through the Holnis Narrows into the inner Flensburg Fjord, but he did. And he stood on the bridge smoking his Brazil as cool as a cucumber and taking us in as though we were on rails.” The reserve which surrounds all new commanders had been broken. Krancke had won the approval of his men.

As every new man came on board he was handed instructions calculated to provide him with a little exercise, for he had to report, one after the other, to about twenty different posts where he was told his action station, his fire station, his gas-alarm station and so on, and provided with a sleeping place, a hammock, a lifebelt, and supplementary clothing which included tropical kit. Any questions as to the last-named were discouraged: “Don’t ask questions; tropical kit belongs to standard issue these days.” A man could spend his time wondering in the navy, but for the sake of his own peace of mind he soon gives it up.

By October the Scheer was moored in Gotenhafen and her crew had far too much to do to waste time wondering. Munitions of all calibres were taken on board, and machine-parts, tool cases and supplies in such quantities that it almost began to look as though the Scheer were going to establish another dockyard somewhere. And lorry after lorry came driving up with foodstuffs. Between decks, cases and sacks began to pile up until there was soon hardly room to pass along the companion ways. And there was so much cabbage that the men even began to fear that their new Captain was a vegetarian.

Rumours were flying around of course, but none of them could be confirmed. The fact was that apart from the Captain himself no one knew anything. The secret of what Naval Operations Command intended to do with the Scheer had been well kept, so well in fact that none of the busily speculating rumour-mongers on board really believed that in view of what had happened to the Graf Spee, their own ship would be sent out as a commerce raider. Oh, of course, they might make a quick drive into the Greenland Sea, perhaps, a sort of hit-and-run affair, but hardly more than that. But Operational Orders, three typewritten pages of them, were already lying in the Captain’s cabin with the signature of Grand Admiral Raeder on them, and Captain Krancke already knew what they contained.

The rattling, puffing harbour locomotive brought along train after train of goods wagons to where the Scheer was lying, and the work of loading went on day and night. Cheese of all sorts in all shapes and sizes was amongst the many provisions sent along by the Naval Supply Department. Amongst these cheeses was one which arrived in cartwheel shape weighing several cwt. This particular cheese led to an illuminating incident.

The working party carrying them on board consisted of new men, and they were left to their own devices; not an officer or petty officer was in sight.

“How can they expect us to carry these monsters down those ladders,” grumbled one of the sailors, a man named Fietje Martins. “Let’s roll ‘em down.”

For a while all went well; then one of the heavy cheeses fell on a man’s locker below with a terrific crash, bending the metal and breaking the lock.

“Three days for you,” observed a couple of stoker-mechanics who happened to be passing, “unless we can do something about it. Wait a while and we’ll try.”

In a few minutes they were back with tools and to the great relief of Fietje Martins they managed to repair the locker and make it shipshape again. In reply to his thanks they shrugged their shoulders.

“What’s a little thing like that? A pack of cigarettes’ll settle it.”

Martins produced the required pack thankfully, but the two obliging sailors took only one each and pushed back the packet. But they hadn’t finished with him.

“Just a word in your ear,” said one of them. “You’re new, aren’t you. Just remember you’re on board the Scheer, not just any old tub, and do your job properly, the way you’re told to do it.”

Martins stared at him in astonishment.

“Well!” he exclaimed. “Here’s somebody after promotion.”

“No, but when we go out on a job I want to come home safely. If everyone did his job the way you’ve just been doing yours with that cheese none of us’d get home at all. Every man on board the Scheer does his job right. Once you’ve got that, you’ll get on much better. So long. No offence.”

In such and similar ways the comradeship of the ship’s company began to develop until before long whoever kicked over the traces whether on duty or off needed no sergeant at arms to deal with him—his own comrades brought him t...

Table of contents

- Title page

- TABLE OF CONTENTS

- PART ONE-ALONE IN THE NORTH ATLANTIC

- PART TWO-IN THE SOUTH ATLANTIC

- PART THREE-IN THE INDIAN OCEAN