eBook - ePub

The Russian Air Force in the Eyes of German Commanders

- 362 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

The Russian Air Force in the Eyes of German Commanders

About this book

The Russian Air Force in the Eyes of German Commanders by Generalleutnant a. D. Walter Schwabedissen, is one of a series of historical studies written by, or based on information supplied by, former key officers of the GAF for the United States Air Force Historical Division.

The overall purpose of the series is twofold: 1) To provide the U.S. Air Force with a comprehensive and, insofar as possible, authoritative history of a major air force which suffered defeat in World War II, a history prepared by many of the principal and responsible leaders of that air force; 2) to provide a firsthand account of that air force's unique combat in a major war, especially its fight against the forces of the Soviet Union. This series of studies therefore covers in large part virtually all phases of the Luftwaffe's operations and organization, from its camouflaged origin in the Reichswehr, during the period of secret German rearmament following World War I, through its participation in the Spanish Civil War and its massive operations and final defeat in World War II, with particular attention to the air war on the Eastern Front.

In World War II the Russian Air Force came of age. The men most vitally concerned with this, aside from the Russians themselves, were commanders in the German armed forces. The experience of these commanders, then, constitutes a unique source for information on an organization whose capabilities, both past and future, are of vital concern to the world.

The chief German experience with the Russian Air Force derives from World War II. It was during this period that the Russians learned most from the Germans and the Germans learned most about the Russians.

This study exploits this broad German experience. Compiled from the official records of the German Air Force and from reports written by German commanders who saw action in the Russian campaign, it documents many of the Russian Air Force's achievements as well as its failures.

The overall purpose of the series is twofold: 1) To provide the U.S. Air Force with a comprehensive and, insofar as possible, authoritative history of a major air force which suffered defeat in World War II, a history prepared by many of the principal and responsible leaders of that air force; 2) to provide a firsthand account of that air force's unique combat in a major war, especially its fight against the forces of the Soviet Union. This series of studies therefore covers in large part virtually all phases of the Luftwaffe's operations and organization, from its camouflaged origin in the Reichswehr, during the period of secret German rearmament following World War I, through its participation in the Spanish Civil War and its massive operations and final defeat in World War II, with particular attention to the air war on the Eastern Front.

In World War II the Russian Air Force came of age. The men most vitally concerned with this, aside from the Russians themselves, were commanders in the German armed forces. The experience of these commanders, then, constitutes a unique source for information on an organization whose capabilities, both past and future, are of vital concern to the world.

The chief German experience with the Russian Air Force derives from World War II. It was during this period that the Russians learned most from the Germans and the Germans learned most about the Russians.

This study exploits this broad German experience. Compiled from the official records of the German Air Force and from reports written by German commanders who saw action in the Russian campaign, it documents many of the Russian Air Force's achievements as well as its failures.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access The Russian Air Force in the Eyes of German Commanders by Generalleutnant Walter Schwabedissen in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & European History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Chapter 1 — DEVELOPMENT AND APPRAISAL OF RUSSIAN AIR POWER PRIOR TO THE RUSSIAN CAMPAIGN

Section I: Development from 1918 to 1933{4}

As organic elements of the Army and Navy, Russian air units in World War I achieved no significant and independent development. Apart from their large 4-engine Sikorski model, constructed in 1914, and a remarkable achievement at that early date, the Russian air forces of 1914-18 were largely dependent on Allied support, their units being equipped primarily with French and British fighter aircraft. In the 1915-17 period the Russian aircraft industry produced approximately 1,500 to 2,000 aircraft annually.

At the commencement of the revolution in 1917 about 500 obsolete aircraft were available, most of them French models, and only two aircraft factories were in existence. No aircraft at all were produced in Russia from 1918 to 1920. The Bolshevist Revolution, civil war, and the war with Poland resulted in such complete destruction of the Russian air forces that it became necessary in the early twenties to create an entirely new air force.

Lenin, and later Stalin, clearly realized the necessity to create a strong air force and energetically tackled the difficult problem. Neither in the military nor in the technical or industrial fields was the Soviet Union in any position to develop a new air force with its own resources. Help had to be sought abroad, partly through purchasing foreign aircraft, but in a greater measure through engaging foreign military and technical experts.

In the military field the good Russo-German relations in the 1920’s provided the essential conditions for this assistance.{5} Russian air officers were given careful training in the general staff courses conducted by the Reichs Ministry of Defense in Berlin, and in 1924 an aviation training school was established at the Russian airfield of Lipetsk—approximately 150 miles south of Moscow—for officers of the German Reichswehr,{6} as Germany’s post-World War 100,000-man national defense establishment was called. The experience gained by the German officers and the operational and training principles developed for the Luftwaffe were made available to the air forces of the Soviet Union.{7}

It is thus not surprising that most German views on the employment of air power were adopted by the Russians. The general view of the Reichswehr at that time was that air power must be auxiliary to the Army and the Navy. Although carefully studied, the theories of Douhet{8} and Rougeron{9} had not yet been accepted. Consonant with German views, the new Russian Air Force was developed as an auxiliary of the Army and the Navy, so that main emphasis was placed on the establishment of fighter, reconnaissance, and light bomber units. Whereas the Luftwaffe later became an independent branch of the armed forces with far-reaching missions of its own, the Soviet air forces remained essentially an auxiliary of the Army and the Navy.

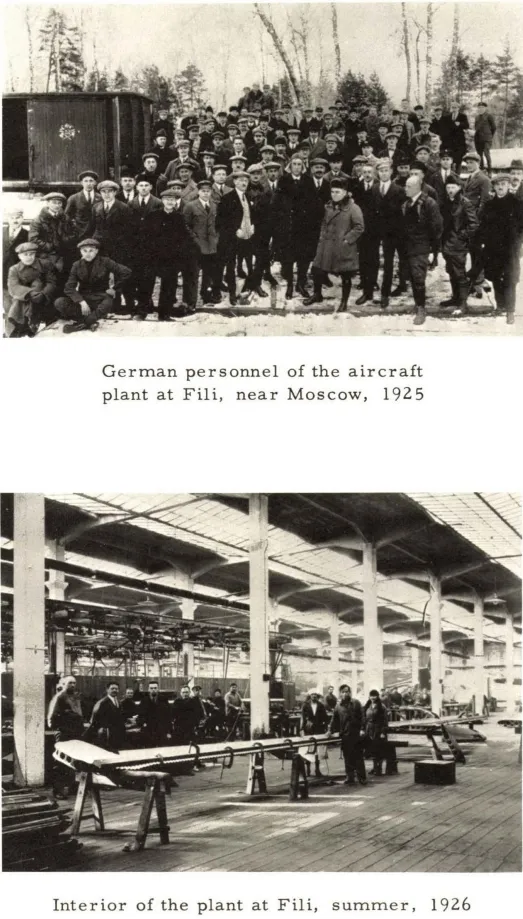

Foreign influences, however, were far more potent in the technical fields than in the military. Here again Germany initially took first place. In 1923, as a result of Russia’s special interest in the construction of metal aircraft, the firm of Junkers, Dessau, established a branch factory{10} for the construction of all-metal aircraft at Fili, on the outskirts of Moscow. There, fuselages and, on a smaller scale, Jumo-L-5 engines were manufactured. The factory was under German management and employed German engineers, designers, master craftsmen, and foremen, and it was here that Russian engineers and skilled workers received their training.{11} In addition to repairing existing Junkers aircraft of the F-13, W-33, and A-20 types, the factory engaged primarily in the construction of Junkers 21 aircraft, a high-wing cantilevered monoplane powered by a Jumo-L-5 engine. The plane, intended as a multi-purpose model, was placed in serial production and introduced as standard equipment for Soviet air units. Approximately 100 of these aircraft were produced by the end of 1925. Other types produced, but not in series, were the Ju-22, an all-metal high-wing single-seater fighter, and the K-30, a 3-engine bomber. When this stage was reached the Russians thought that they had learned enough and commenced producing independently, so that the 25-year contract with Junkers came to an early end in 1927. The factory at Fili was taken over by the Soviets as their twenty-second aircraft factory.

Through their collaboration with Junkers, the Russians acquired an exemplary system of metal construction and material testing, and an excellently equipped engine construction workshop. Furthermore, large numbers of Russian engineers, designers, technicians, draftsmen and other skilled workers received training under the contract.

In the field of practical science the Soviets also profited greatly from the close collaboration of German specialists with the Central Institute of the Soviet Air Forces which will be referred to in this study as the ZAGI.{12} The institute was under the direction of Professor Tupolev,{13} who later became famous for his aircraft designs. A special role was played in this collaboration by Professor of Aerodynamics Günther Bock, who was taken by the Russians to the Soviet Union after World War II, has since returned to Germany and is presently on the staff of the Technische Hochschule at Darmstadt.

In retrospect there can thus be no doubt that the relatively quick progress made by the Russians, despite serious difficulties in the initial years, was due primarily to assistance from German military and technical personnel.

Compared with German influences on the development of Soviet air power, those of other foreign countries, during the first few years, were small. They remained more or less restricted to the purchase of Italian, French, British, and Dutch aircraft and later to the copying of foreign fuselages and engines. Italy and Britain played a not inconsiderable role, Italy with its Combat twin-engine [Komtal] bomber—powered by Fiat engines, and Britain with its De Haviland 9a, and with Bristol, and Napier engines. It must be remembered that in these early years Soviet air units were equipped almost exclusively with foreign fuselages and, more particularly, with foreign aircraft engines.

While drawing extensively on foreign assistance in the development of its air force, the Soviet Union made strenuous efforts to make itself independent of this assistance. A number of steps were taken toward this goal. The first and most important of these was the creation of an efficient aircraft manufacturing industry. The program was logical and determined, particular stress being placed on the establishment of factories for the production of fuselages, aircraft engines, and accessories. In addition to the ZAGI previously referred to, a Central Directorate of the Soviet Air Forces was established in Moscow to direct the program. The ZAGI was assigned responsibility for all technological and construction measures adopted in connection with air armament.

The program was given added impetus by the First Five-Year Plan (1928-1932), In 1930 management of the air armament program was decentralized. Separate directorates were established for military and civil aviation and the overburdened ZAGI was relieved of some of its responsibilities through the establishment of a separate institute for aircraft engines (ZAMI), and another for conducting research on materials (VIAM). Most of the factories of the air armament industry at that time were established in European Russia west of the Urals, in the areas around Moscow, Leningrad, and in the Donets Basin. Besides Tupolev, other designers, including Ilyushin, Mikoyan, and Lavochkin{14} made their appearance with models of their own, although these were frequently patterned on foreign prototypes.

In spite of all efforts the targets of the first Five Year Plan were not even approached. Thus, an annual output of 600 TB-1 and TB-2 bombers{15} had been projected, of which barely 50 percent was achieved. In the case of single-seater types—the main field of endeavor—the discrepancy between projected and actual output was almost if not quite as pronounced. The most serious difficulties encountered were the lack of machine tools, short supplies of aluminum and copper, and the lack of adequate numbers of skilled personnel.

In frequent cases quality was sacrificed for quantity and on the whole the manufacture and assembly of aircraft engines was so far in arrears that at the end of the first Five Year Program most of the first line aircraft were still powered by foreign engines. In addition, Russian fuselages were technically inferior to those of foreign make.

The program was also hampered by the purge of Trotzkyites, which began in 1928.

In spite of all defects and setbacks the Five Year Plan produced one important result: the Soviet air armament industry could be considered largely independent of foreign support. Other results included an increased output from Soviet aircraft factories which managed to produce approximately 2,000 planes annually; initiation of rationalized methods in the aircraft industry; and the discovery of a light metal—Kolchug aluminum—a Russian achievement. The progress thus made was also due in no small measure to the experience gained in the field of knock-proof fuels. In the manufacture of aircraft engines a logical course was being followed: concentration on the production of a small number of efficient types.

Another measure which furthered the development of the Soviet air forces was a program to expedite the training of aviators, ground service, and other specialized personnel. Here the Soviet Government succeeded, through a gigantic propaganda campaign, in arousing an enthusiastic national interest in aviation. A society, “Friends of the Russian Air Forces,” was founded in 1923 and had as many as 1,000,000 enrolled members barely two years later. Generous measures to promote glider aviation on a large scale did much to arouse the enthusiasm of the younger generation and assisted materially in the pre-training of flying and technical personnel. Together with the (in some respects) ruthless methods of labor management of the totalitarian government, the inborn Russian characteristics of tenacity, endurance, frugality, and, particularly, obedience, promoted the speedy development of a solid foundation of suitable personnel. The widespread assumption that the average Russian has little, if indeed any, technical aptitude was soon proved a fallacy. The opposite was found to be true.

Although a long time was still to pass before the Soviet air forces and air armament industry would have an adequate reservoir of skilled labor to draw upon, the early results of the personnel training program certainly cannot be considered unsatisfactory since almost all personnel had to be trained from scratch.

While they were creating a military air force, the Russians took steps to promote civil aviation. The result was the development of a giant civil air transport service. Partly for propaganda purposes, the service used only aircraft of Russian manufacture. However, foreign aircraft were used on the route serviced by the Deruluft, a Russo-German airways company formed in 1921.{16} Military aviation and the aircraft industry profited to a certain extent from the use of installations of the civilian airlines and from the experience gained in civil aviation.

The stages in the development of Soviet military air power in the 1920-33 period were approximately as follows:

1923: The first squadrons were placed in service.

1928: The strength of the Russian air forces reached approximately 100 squadrons totalling roughly 1,000 aircraft. The units were stationed and trained almost exclusively in western Russia—in the Leningrad, Moscow, Smolensk, Rostov, Kiev, Sevastopol, and other areas.

1930: Reports showed the existence of 20 brigades with 1,000 first line aircraft and 25 aviation schools of various types.

1933: Strength estimated at 1,500 first line aircraft at the end of the first Five-Year Plan. Annual production approximately 2,000 aircraft.

Russi...

Table of contents

- Title page

- TABLE OF CONTENTS

- INTRODUCTION TO THE SERIES

- CHARTS

- MAP

- FOREWORD

- PREFACE

- AUTHOR’S INTRODUCTION

- Chapter 1 - DEVELOPMENT AND APPRAISAL OF RUSSIAN AIR POWER PRIOR TO THE RUSSIAN CAMPAIGN

- Chapter 2 - THE SOVIET AIR FORCES FROM THE OPENING OF THE RUSSIAN CAMPAIGN TO THE END OF 1941

- Chapter 3 - THE RUSSIAN AIR FORCE IN 1942 AND 1943

- Chapter 4 - THE RUSSIAN AIR FORCE ACHIEVES AIR SUPERIORITY

- Appendix 1 - LIST OF EQUIVALENT LUFTWAFFE AND USAF GENERAL OFFICER RANKS

- REQUEST FROM THE PUBLISHER