- 32 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

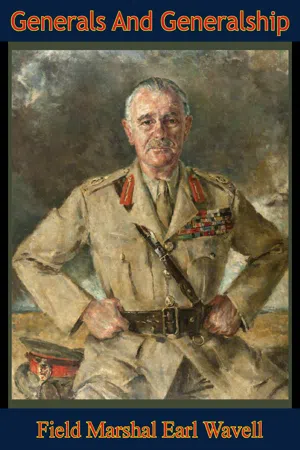

Generals And Generalship

About this book

Field Marshal Wavell was one of the most successful British Army commanders of the Second World War, often given the toughest assignments, usually greatly outnumbered and with few resources. In this short volume he shares the distilled wisdom on the qualities, mental, moral and political that are necessary for successful leadership.

A long forgotten classic of military thought and leadership.

"These lectures by General Wavell […] show very clearly how he and the army under his direction have gained their great victories in Africa and why they will gain others. For these lectures, though delivered over two years ago, could only have been delivered by a man capable of winning and keeping the confidence of all men in all walks of life. They deal with the relationships between man and man, on which must be founded both the success of an army and the success of a whole nation at war. I am glad indeed to think that they will have a wide audience, and particularly among soldiers, for whom they have deep lessons."—From Foreword by Field Marshal John Dill

A long forgotten classic of military thought and leadership.

"These lectures by General Wavell […] show very clearly how he and the army under his direction have gained their great victories in Africa and why they will gain others. For these lectures, though delivered over two years ago, could only have been delivered by a man capable of winning and keeping the confidence of all men in all walks of life. They deal with the relationships between man and man, on which must be founded both the success of an army and the success of a whole nation at war. I am glad indeed to think that they will have a wide audience, and particularly among soldiers, for whom they have deep lessons."—From Foreword by Field Marshal John Dill

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

III—THE SOLDIER AND THE STATESMAN

MY third lecture deals with the relations of higher commanders to their masters, the statesmen who direct them. This is difficult and controversial ground. As you are aware, the relations between soldiers and statesmen were not too happy in the late War. Broadly speaking, the politician charged the soldiers with narrowness of outlook and professional pedantry, while the soldier was inclined to ascribe many of his difficulties to “political interference.” This friction between civil and military is, comparatively speaking, a new factor in war, and is a feature of democracy, not of autocracy.

In old times the difference between civil and military was narrow, in fact soldiers and statesmen were usually interchangeable. In the history of classical Greece you may recall the story of Cleon and Nicias in the Peloponnesian war between Athens and Sparta. The demagogue Cleon, leader of the opposition, criticized the conservative Nicias. The latter, thinking to corner his opponent, turned on him with a challenge, “Go you then and take command and see if you can do any better.” Unfortunately for Nicias, and unfortunately for Athens in the long run, Cleon accepted the challenge and won a striking, though lucky, victory. In ancient Rome an indispensable qualification for command in the field was to have passed through all the ranks of the magistracy—i.e. of the civil administration of the State. Generals, when required, were chosen from the heads of the Civil Service. If you read the “Lays of Ancient Rome” in your younger days you may remember how, according to Macaulay, the fathers of the city, on an emergency arising, came to the very sensible decision that:—

“In seasons of great peril

‘Tis good that one bear sway,

Then choose we a dictator

Whom all men shall obey.”

“And let him be dictator

For six months and no more,

And have a Master of the Knights

And axes twenty-four.”

All very simple, you see. It would perhaps be easier for Europe if dictators were still selected for the same period.

The history of Hannibal perhaps provides the first striking example of a general’s plans being ruined by political neglect, from one of the earliest democracies. For many years rulers of States usually led their armies in the field (e.g. Alexander, the English kings, Gustavus Adolphus, etc.), and, of course, no question of political interference arises. Marlborough was in a peculiar position. Besides Commander-in-Chief of the army in the field, he was virtually Foreign Minister, and directed the foreign policy of the country from his headquarters. He also, at his zenith, practically exercised the powers of the Prime Minister in home politics. Yet no general probably had his plans ruined so often by the interference of the Dutch statesmen and the enmity of his rivals at home. He bore it all with the same serenity of spirit that he showed in the field of battle. A very great man, for all his faults; and undoubtedly, I think, our greatest military genius.

“Political” generals are anathema to the British military tradition, yet most of the best British commanders had political experience. Cromwell was for many years a member of Parliament before he took to soldiering. Marlborough, of whom we have just spoken, had far more experience of political intrigue than of military service when he began his career as a general. Wellington had been a member of both Irish and British Parliaments. Sir John Moore sat in Parliament; so did Craufurd; so did Graham (afterwards Lord Lynedoch), the victor of Barossa, who first took to soldiering at the age of 44. On the other side, in the French revolutionary wars, we meet the political commissar often hampering operations, till Napoleon chooses himself as a dictator, not for six months but “for the duration.”

The next example to which I would call your attention (I am ranging over the field of military history rather like a wild spaniel putting up birds and hares all over the place) is the American Civil War. The relations of that great and wise man Lincoln with his generals are well worth study. Having after many trials found a man whom he trusted in Grant, he left him to fight his campaigns without interference. I am going to read you an extract from a letter written by Lincoln to one of his generals which will, I think, show you his quality.

ABRAHAM LINCOLN TO HOOKER ON APPOINTMENT TO COMMAND THE ARMY OF THE POTOMAC

“I have placed you at the head of the Army of the Potomac. Of course I have done this upon what appears to me sufficient reason, and yet I think it best for you to know that there are some things in regard to which I am not quite satisfied with you. I believe you to be a brave and skilful soldier, which, of course, I like. I also believe you do not mix politics with your profession, in which you are right. You have confidence in yourself, which is a valuable, if not an indispensable quality. You are ambitious, which, within reasonable bounds, does good rather than harm; I think that during General Burnside’s command of the Army you have taken counsel of your ambition and thwarted him as much as you could, in which you did a great wrong to the country and to a most meritorious and honourable brother officer. I have heard, in such a way as to believe it, of your recently saying that both the Army and the Government needed a dictator. Of course it was not for this, but in spite of it, that I have given you the command. Only those generals who gain successes can set up as dictators. What I now ask of you is military success, and I will risk the dictatorship. The Government will support you to the utmost of its ability, which is neither more nor less than it has done and will do for all commanders. I much fear that the spirit which you have decided to...

Table of contents

- Title page

- TABLE OF CONTENTS

- ABOUT THE AUTHOR

- FOREWORD

- I-THE GOOD GENERAL

- II-THE GENERAL AND HIS TROOPS

- III-THE SOLDIER AND THE STATESMAN

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Generals And Generalship by Field-Marshal Earl Wavell in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & British History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.