- 239 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

Some historians postulate that the First World War would have ended several months earlier if it were not for the successful strategy and deception employed by German President Paul von Hindenburg (1847-1934) and General Erich Ludendorff (1865-1937) of the German High Command.

It is believed that both Hindenburg and Ludendorff realized as early as 8 August 1918 that victory was not possible; however, neither could conceive of accepting defeat. Therefore, in late September 1918, a carefully planned 'revolution from above' resulted in the High Command being placed under government control which gave Hindenburg and Ludendorff the opportunity to shift the responsibility of seeking an armistice and military defeat from the High Command to the civilian government and the Reichstag.

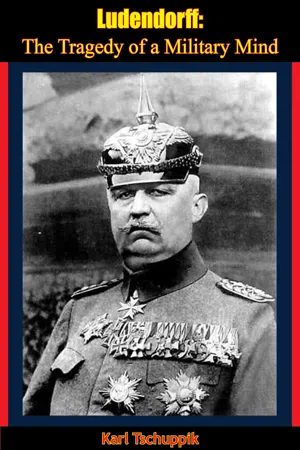

First published in its English translation in 1932, this book by Austrian writer and journalist Karl Tschuppik is an analysis of Erich Ludendorff. The author demonstrates the power the High Command had over the Chancellor and Kaiser, and the book provides a useful in understanding the High Command's power and for obtaining quotations regarding the High Command's power.

It is believed that both Hindenburg and Ludendorff realized as early as 8 August 1918 that victory was not possible; however, neither could conceive of accepting defeat. Therefore, in late September 1918, a carefully planned 'revolution from above' resulted in the High Command being placed under government control which gave Hindenburg and Ludendorff the opportunity to shift the responsibility of seeking an armistice and military defeat from the High Command to the civilian government and the Reichstag.

First published in its English translation in 1932, this book by Austrian writer and journalist Karl Tschuppik is an analysis of Erich Ludendorff. The author demonstrates the power the High Command had over the Chancellor and Kaiser, and the book provides a useful in understanding the High Command's power and for obtaining quotations regarding the High Command's power.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Ludendorff by Karl Tschuppik, W. H. Johnston in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & British History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

CHAPTER I — BEGINNINGS

Early Career—Schlieffen and Cannae—The Masurian Lakes and Tannenberg

IT is the early morning of August 7th, 1914; a German officer strikes with the pommel of his sword upon the gates of Liège. Major-General Ludendorff is alone except for his aide-de-camp. The chauffeur of the Belgian car who brought the two officers to the spot watches them with amazement—surely the man does not hope to capture a citadel with a bare sword? The General and his aide-de-camp had expected to find the citadel in the hands of the advance guard of their brigade; but not a single German soldier is in sight. The garrison of the citadel answer the knocking and open the gates. The two officers continue on their audacious course and, undeterred by the sight of some hundreds of Belgian soldiers, penetrate into the courtyard. The defenders are paralysed by surprise; soon after, a German regiment is heard approaching, and the garrison surrenders to General Ludendorff.

The important fortress of Liège, whose function it was to guard the approaches of the valley of the Meuse, had fallen without one of its outer line of forts having been touched. Twelve powerful forts, hitherto regarded as impregnable, guarded the fortress; not one of them was in the hands of the Germans. General von Emmich with a force of six weak brigades at his disposal, succeeded in carrying only one of these between the forts and into the citadel. To this brigade Ludendorff had attached himself, and when the commanding officer fell in action Ludendorff took over the command. It was in this capacity that he went through his first battle and saw his first man killed. On a later occasion he noted in his diary: “I shall never forget the sound made by a bullet striking a human body”.

The night of the 6th to the 7th of August passed in unendurable suspense. Alone within the circle of forts and without news of the other units, the brigade might at any moment be cut off and surrounded. In spite of this danger, Emmich gave orders in the morning to occupy the town. The advance guard, which had been ordered to occupy the citadel, lost its way, and when Ludendorff appeared before the walls he was alone with his aide-de-camp. In later days he referred to the advance upon Liège and the capture of this city as the “most treasured memory” of his life.

It was an accident which had given to Ludendorff this position in the forefront of the battle. He admits himself that he had been intended to take part in the advance on Liège in the capacity of a casual spectator and without holding any executive post. His real place was with the Staff of the Second Army, where he had been attached to General von Lauenstein, the Chief of General Staff, as Deputy-Chief of Staff. This appointment corresponded roughly to Ludendorff’s age and past career. For some years he had served with his infantry regiment at Wesel, Wilhelmshaven, Kiel, Frankfurt-an-der-Oder, and Thorn; later he had been stationed as General Staff Officer at Glogau and Posen, and from 1904 to 1913 he had worked in the offices of the General Staff at the War Office, where he had spent eight years in the Mobilisation Department, finishing this part of his service as head of the department. At this time plans for an increase in the army were being worked out, and in his capacity as head of his department Ludendorff had been working since 1912 with all the energy and tenacity at his disposal for the incorporation of three new Army Corps. It was this self-imposed advocacy of the cause of the army which led to his relegation from the General Staff: he was given the command of a brigade of infantry stationed at Düsseldorf. In April 1914, at the age of forty-nine, he obtained a brigade at Strasbourg. On the outbreak of war he was attached to the Second Army.

During the advance on Liège, Ludendorff was acting as liaison officer. It was his function to maintain contact between General von Bülow, commanding the Second Army, and the Storm Troops of General Emmich. After the capture of the fortress it was intended that he should return to the Army Staff. Had he done so, he would have advanced with Bülow through Belgium and Northern France to the Marne. As it was, Liège was for Ludendorff what Toulon was for the Young Officer of Artillery.

In 1793, while the French Revolutionary Government was carrying through its policy of general conscription, every officer who showed signs of boldness and talent might hope to rise to the rank of general, while generals who met with misfortune were not saved from the Tribunals of a Republic by their personal courage. Stendhal remarks that this apparently absurd system, which offered a suitable target for the sarcasms of all the Legitimists in Europe, provided France with all her greatest commanders. Once promotion had become a matter of routine, the system produced nothing but mediocrity—generals like Macdonald, Oudinot, Dupont, and Marmont, whose armies between 1808 and 1814 achieved for Napoleon nothing but defeats.

It is worth asking whether Stendhal’s criticism of Revolutionary France can be applied to the armies of Imperial Germany, and whether age and seniority were of greater importance than boldness and talent. The name of Ludendorff had been familiar in the High Commands and among all the officers of the General Staff, but since 1913 he had fallen into oblivion. It was Liège and the Order pour le Mérite which brought Ludendorff back from obscurity and into favour. As the dangers of a war on two fronts began to emerge, men began to look towards Ludendorff, and on the 22nd of August he was instructed to take up his command on the Eastern front.

“A difficult task is being entrusted to you, one more difficult perhaps than the capture of Liège”, Moltke, the Chief of General Staff, wrote to Ludendorff. “I know of no other person whom I trust as implicitly as yourself. Perhaps you may succeed in saving the position in the East....Your energy is such that you may still succeed in averting the worst.” And General von Stein, the Quartermaster General, accompanied Moltke’s appeal with the words: “Your place is on the Eastern front. The safety of the country demands it.” This appeal in the hour of trouble must have sounded to Ludendorff like the voice of justice. “I know of no other person”—could it be that fate was beginning to make good the faults of the past? Ludendorff calls back to his mind the privations of his life: “My parents were far from wealthy, and their faithful work was not rewarded by riches on earth. We lived in a very small way....My father and mother were fully occupied with anxiety for their six children....When I was a young officer I had a hard struggle of it to make my way.” He then touches upon a particularly painful spot. For a long period he had been destined, in the event of war, to be the head of the directorate of military operations. His transfer to Düsseldorf had put an end to this plan. It was Ludendorff’s successor in the Great General Staff, Colonel von Tappen, who became the assistant of Moltke.

Ludendorff’s appointment as Chief of Staff of the Eighth Army in Eastern Prussia was one to satisfy the loftiest ambition. “It was an inspiring thought”, Ludendorff writes, “that at this crucial moment I was serving my country at a decisive post.” The German force in the East consisted of four Army Corps, one Reserve Division, and one Cavalry Division; it was opposed by two Russian armies, each of which was superior to the German army of the East. The unexpected arrival of General Samsonov’s Warsaw army, which marched at night and remained under cover of the forests during the day, compelled the German Commander-in-Chief, General von Prittwitz, to break off the operations against the Vilna army commanded by General Rennenkampf and to withdraw behind the Vistula. A little later Lieutenant-Colonel Hoffmann, a member of his Staff, induced him to change his view of the situation, and von Prittwitz himself gave the first orders for an advance against the Warsaw army; but it was now too late, and both he and his Chief of Staff, Count Waldersee, were recalled. On the 23rd of August, at four o’clock in the morning, the new Commander-in-Chief on the Eastern front, von Hindenburg, joined Ludendorff in his train at Hanover. This was the first meeting between Hindenburg and his Chief of Staff.

The two men whom the train was carrying from Hanover to Marienburg are not surrounded by that glamour which a kind of traditional superstition loves to attach to military leaders. Ludendorff himself would have declined to enter into abstract considerations upon the nature of generalship. He was devoid of that mysticism which demands superhuman qualities and the protection of higher powers for the captain who rides the whirlwind and directs the storm. Ludendorff knew no uncertainty; his confidence in himself and his abilities rested upon a sure foundation of acquired knowledge and inborn personal qualities. In every detail he was the pupil of Alfred von Schlieffen, the last great master who moulded the form of the Prussian General Staff, von Schlieffen was too clear a thinker and too fair-minded a critic of the German strategy of the 19th century not to know that a general is not made by training or by appointment. The shepherd David, destined to be the conqueror of the Philistines, was anointed by Samuel to command the King’s army, and Hannibal was dedicated as a child to the career of arms upon the altar of Baal. Caesar attributed his good fortune at Dyrrhachium to superhuman powers, and Cromwell felt himself to be the chosen instrument of the Lord. Schlieffen disposes of these fancies in a brief sentence worthy of Frederick: “If the incipient general relies upon his divine call, his genius, or the protection and support of higher powers, his hopes of victory are scanty”. Ludendorff’s sentiments were the same. The general’s task is the destruction of the enemy, even if the latter’s forces are stronger and his position and intentions unknown. A happy gift of improvisation does not suffice for this; the unknown can be mastered only by the skilful application of the stored-up wisdom of the Prussian General Staff.

Clausewitz has laid it down as a general proposition that the differences between the nations cannot be formulated in an epigram and can be found only in the sum total of their intellectual and material relations to each other. This general proposition is true in particular of the differences between the methods of warfare. Every nation in arms carries beneath its uniform its acquired characteristics and its past history, and a general, although he may imagine himself to be a free agent, is in fact the servant of a tradition no less strong than the walls that encircle a fortress. Only a man of genius succeeds at times in breaking through these bonds.

The world for Ludendorff was of a Spartan simplicity: he knew no uncertainty and no problems. The son of an obscure Pomeranian family never doubted that the Prussian world which he first saw as a child and learned to know as a cadet and officer was the best of all possible worlds. He had not the critical eyes which, while not blind to the defects of creation, are necessary also in order to discern the essential from the irrelevant and to pierce through the trappings to the man. From early youth he had been trained to receive an order and to obey, and his mind became immune alike to speculation and to doubt. Any flaws and faults in the well-ordered picture of the Prussian State were interpreted by Ludendorff from an ethical point of view: they were no more than the effects of the infirmity of individuals. Surely the rise of Prussia was its own justification; surely the Prussian General Staff wielded the most admirable instrument of war, and surely the principles of Schlieffen possessed infallibility. Every staff officer of Ludendorff’s generation had absorbed the principles of Schlieffen, and their validity was universal, like that of the laws of mathematics. If Gneisenau was the founder of the Prussian General Staff, and the elder Moltke had inspired it with new life, then Schlieffen’s function had been to perfect the tradition of Moltke. The General Staff becomes a complicated technical office whose function is the conduct of war.

If we discard technical language, Schlieffen’s guiding idea can be easily explained. It is based on the fact, proved by experience, that it is easier to overcome the enemy by attacking him in flank or rear than by meeting him face to face. Boys when they play at soldiers or Red Indians arrive at this advantageous method without the help of a military college. In these games, that group will be in the best position which arranges its forces so that one part faces and attacks the enemy while the two other parts advance on his right and left and threaten him on either flank and in the rear. Old and simple as is this rule, it has been practised successfully only by captains of genius.

It was Hans Delbrück, the great military historian, who reconstructed the battle of Cannae, and thus enabled Schlieffen to make this classical example of the battle of so-called double outflanking the ideal of all campaigns in general. On the 2nd of August 216 B.C., Hannibal, with 50,000 men, had taken up a position near the village of Cannae on the Aufidus, in the Apulian plain. He was opposed by 69,000 men under Terentius Varro. Faced by a superior enemy and with the sea in his rear, Hannibal was in a more than unfavourable position. The Romans had three lines of battle, the hastati, the principes, and the triarii, this was a classification by age, and the three classes corresponded approximately to the troops with the colours, the reservists, and the Landwehr of a modern army. Where this arrangement was followed, only the first line actually fought, carrying its reserve formations with it “like a snail carrying its house upon its back”. These reserve formations waited under arms behind the first line until their turn should come, and it was only then that the second and, in case of need, the third maniple went into action. Thus the full forces of a Roman army were never engaged simultaneously, and only a fraction was in action at any given time. At Cannae, Hannibal, faced by this rigid and clumsy mass, whose reserves waited passively until the fighting formations had been decimated, divided his army into three mobile groups which could be brought into action simultaneously. His forces were weaker than those of the Romans; his front line, consisting of infantry, was drawn up in shallow formation with cavalry on either wing; behind them were drawn up his best troops, the heavily armed Carthaginians. In the first shock of battle Hannibal’s infantry was thrust back by the sheer weight of the Roman assault. This movement, however, was brought to a stop as soon as the Carthaginian attacks on the two Roman flanks and the cavalry charge delivered upon their rear made themselves felt. The Roman square, exposed to an attack from every side, was eventually crushed in, with the loss of 48,000 men, while Hannibal’s losses only amounted to 6000.

This battle, fought over 2000 years ago, became Count Schlieffen’s ideal. He proceeded to investigate military history, and particularly the campaigns of Frederick the Great and Napoleon, in an attempt to see how closely their methods approximated to the ideal battle of annihilation. His rigorous criticism of Moltke’s two campaigns, that against Austria and that against France, had the one aim of demonstrating that Moltke’s plans invariably aimed at inflicting a Cannae upon his enemy: where the ideal of a battle of annihilation was not attained, the fault did not lie with the Chief of the General Staff but with the refractory Army Commanders. The whole trend of thought of the General Staff and the will of budding generals came to be trained with one aim in view, and with one aim alone—Cannae.

During the journey to Marienburg, Ludendorff had leisure to examine the prospects of the impending battle. His position was less favourable than Hannibal’s. The enemy was more than twice as strong as his forces, a disadvantage attaching inevitably to a war waged on two fronts; for while the army of the West was attacking the enemy with every available man, the army of the East had to remain on the defensive until the troops from the West should be set free. The position, moreover, was far worse than had been anticipated. The Russian mobilisation had been unexpectedly rapid, and Moltke’s letter to Ludendorff did not exaggerate. “Perhaps you will be in time to avert the worst.” The prospect was dark indeed.

The earliest plans for a war on two fronts had been worked out under Schlieffen, who had foreseen a withdrawal behind the Vistula in case of necessity. The rapid advance of Samsonov’s army endangered this line of defence, since it was possible that he might reach the Vistula before the Germans. A comparison of forces, and every other military consideration, made a successful defence appear improbable and a German victory impossible.

Marienburg, the site of Army Headquarters, was reached by Ludendorff on the 23rd August. He knew that in an all but desperate position he had only one chance. The two Russian armies, commanded respectively by Rennenkampf and Samsonov, were separated by the chain of the Masurian Lakes. The distances, however, were inconsiderable: Rennenkampf was within 30 miles of the retiring German corps and within 55 miles of Samsonov. The German army of the East was thus in a position analogous of that of Benedek in 1866. If Ludendorff followed academic routine and attacked one of the two Russian armies with the whole of his forces, the other army might be attacking his own rear within two days. Thus everything turned on the question whether the two German corps facing Rennenkampf could be withdrawn and made available for a general attack against Samsonov. Ludendorff had already drawn every man who could be spared from the various garrisons, and if he succeeded in gathering all his forces against Samsonov before Rennenkampf began to move, there was a chance that Samsonov might be defeated. Even this, however, was only the first and less difficult half of Ludendorff’s task: after the battle with Samsonov it would be necessary to turn his tired troops against the fresh forces of Rennenkampf.

Military history contains no example of a position as desperate as Ludendorff’s. According to Stendhal’s simple definition, the art of Napoleon consisted in...

Table of contents

- Title page

- TABLE OF CONTENTS

- CHAPTER I - BEGINNINGS

- CHAPTER II - THE RISE TO SUPREMACY

- CHAPTER III - DICTATORSHIP

- CHAPTER IV - DICTATORSHIP (continued)

- CHAPTER V - LUDENDORFF AND THE POLITICIANS

- CHAPTER VI - LUDENDORFF AND THE POLITICIANS (Continued.)

- CHAPTER VII - THE BEGINNING OF THE END

- CHAPTER VIII - GROWING DIFFICULTIES

- CHAPTER IX - THE LAST STRAW

- CHAPTER X - DEFEAT

- CHAPTER XI - COLLAPSE

- CHAPTER XII - THE END

- BIBLIOGRAPHY

- REQUEST FROM THE PUBLISHER