- 227 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Burma Surgeon Returns

About this book

Recent years have offered no more human story than Dr. Seagrave's Burma Surgeon, the account of his medical mission in the jungle wilds and his experiences in the battle of Burma.

Now in this new book, he tells what happened to himself and his hospital unit after the retreat with Stilwell. Safe at last in India, survivors of an epic struggle, bereft of home and family, the doctor and his nurses felt that it was the end of all their hard work and dreams; but they had only one thought—to help drive the Japs out of Burma, and some day to see again their home in Namkham.

Dr. Seagrave extracted from General Stilwell a promise: that when new action developed against the enemy he would save for them "the meanest, nastiest task of all." Burma Surgeon Returns tells how that promise was kept.

Now in this new book, he tells what happened to himself and his hospital unit after the retreat with Stilwell. Safe at last in India, survivors of an epic struggle, bereft of home and family, the doctor and his nurses felt that it was the end of all their hard work and dreams; but they had only one thought—to help drive the Japs out of Burma, and some day to see again their home in Namkham.

Dr. Seagrave extracted from General Stilwell a promise: that when new action developed against the enemy he would save for them "the meanest, nastiest task of all." Burma Surgeon Returns tells how that promise was kept.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

PART ONE—RAMGARH TO THE NAGA HILLS

IN SEVEN terrible months from December 7, 1941, to June, 1942, Japan conquered an empire in the Pacific. Her armies overran Malaya, Burma, the Netherlands East Indies, and the Philippines. China was isolated and Australia menaced. Then, in the summer and late fall of 1942, the Japanese advance was halted at Midway, Guadalcanal, Port Moresby, and at the gates of India.

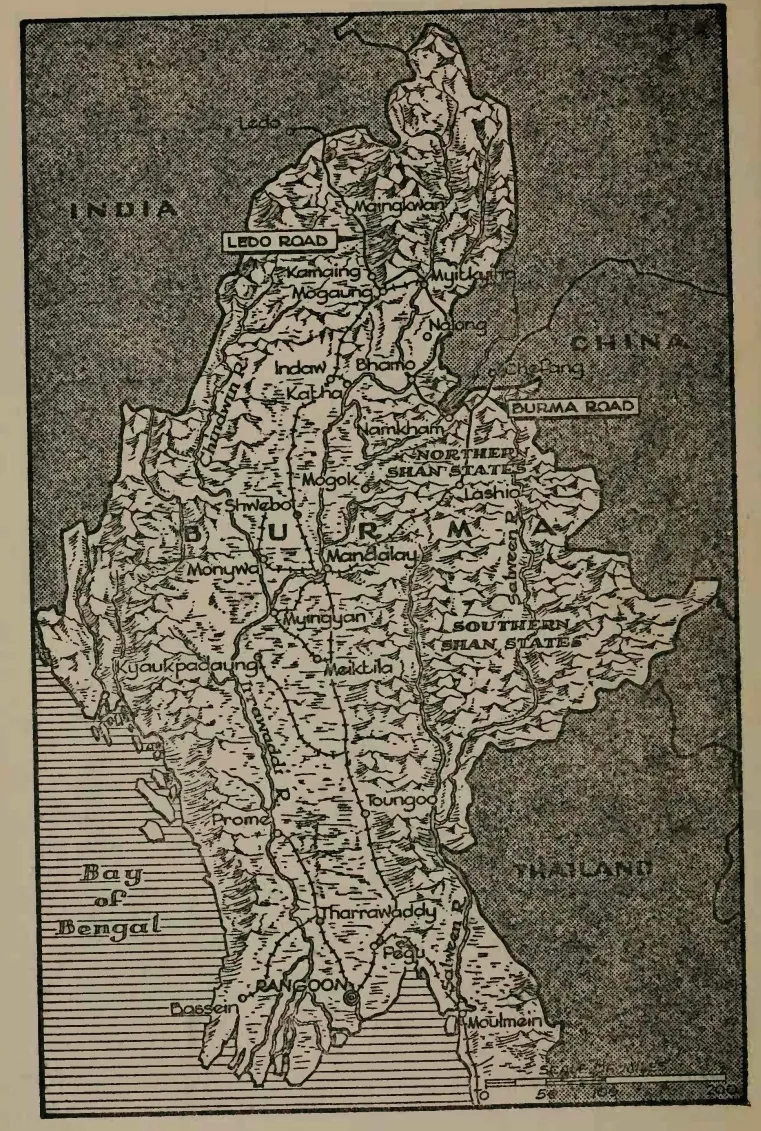

With the main military strength of the United Nations then dedicated to the defeat of Nazi Germany, the American commander in the China-Burma-India theater, General Joseph W. Stilwell, saw only one possibility of effective action against the Japanese. With Chinese troops trained and conditioned in India, he would reconquer a route into northern Burma. American engineers and service troops would build a road through some of the worst terrain in the world from Ledo in Assam to the old Burma Road and Kunming. This would relieve China’s isolation and make it possible to supply her with weapons and equipment for the war against Japan.

It took a long time to nurse back into health the disease-ridden remnants of the Chinese armies which had retreated from Burma into India. It took even longer to train the Chinese soldiers who were flown into India over the Hump. Early in 1943 General Stilwell was ready to begin an operation which many observers regarded as impossible.

1—THE TRAIL OF THE REFUGEES

IT WAS March, 1943, and Burmese refugees were at last on their way back into Burma. At any rate a small group of us were on our way: twelve of the Burmese nurses, Lieutenant Harris of Washington, D.C., and myself. Lieutenant “Bill” Cummings, former charter member of our hospital unit and now on special duty in the wilds of Burma, was our escort.

It had not been easy for us to obtain permission to start back so soon. All of “Uncle Joe” Stilwell’s plans for an early return had been given up for lack of support from home. Uncle Joe—“Grand-daddy” to our nurses—was XYZ on the priorities list in those days. All the supplies and troops America had were pre-empted for what the world—but not the G.I.’s of China-Burma-India or the Burmese refugees—considered the really important theaters. And that meant every other theater except C.-B.-I. We could get along on a face-saving shoestring to make the Chinese remain in the war until we conquered all enemies but hers. Then we would begin to rescue China in earnest.

General Stilwell couldn’t have been very pleased by the meagerness of the resources allotted to him, but distress was never visible in his face or actions. Give him little or give him nothing, he had promised to return the “hell of a licking” the Japs had given him, and he went about his “impossible” task with determination and no complaints. Already his few colored engineers had bulldozed a road from Ledo in North-east Assam to the Burma border in the Pangsau Pass. Now the road was going down into Burma itself—if you can call the Naga Hills and the Hukawng Valley “Burma.” But though the colored boys were working at all hours, with rifles and tommy guns strapped to their backs, Granddaddy knew they would accomplish more if the Chinese troops he had trained for eight months at Ramgarh were to do their share in opening the Ledo Road to China by throwing a screen in front of the road builders. So the Chinese were on their way and we after them.

It was good luck that had secured the assignment for us. Uncle Joe had been on an inspection trip to Ramgarh where I was post surgeon and asked me, as usual, to tell him what we needed.

“Sir,” I said, “since we came to Ramgarh last July we have had no complete set of surgical instruments. The British left in their prisoner of war hospital only a few decrepit instruments, and if Dr. Gurney and I had not brought a lot of our own instruments along with us from Burma we couldn’t have done half the surgery the Chinese Army needed. All the new American hospital units that have come to India have had complete sets of surgical instruments allowed in their Table of Basic Allotments in the States. Service of Supply has no bulk stores from which to fill our own requisitions. Now I understand that at Ledo there are large stocks of surgical instruments in China Defense Supplies destined for China. Since our hospital is working for Chinese troops, may I have your permission to go to Ledo and select instruments both for the Ramgarh hospital and for our unit to use when we finally return to Burma?”

“You’re not planning a one-man expedition into Burma, are you?” the general asked with a twinkle in his eyes.

“No, sir,” I replied with a grin. “I promise not to go beyond the border.” Granddaddy was acquainted with my slippery ways.

“My plane starts for Delhi in the morning and then we’ll go on to Ledo,” the general said. “Be at my headquarters an hour ahead of time.”

I was not late for that appointment.

We drove to the airport in Ranchi and took off in “Uncle Joe’s Chariot.”

One “Cook’s Tour” of Delhi is all anyone with a grain of sense ever wants, and I’d had that experience eight years before. So after I got my order from the Theater Medical Supply officer for whatever useful instruments I might find in Ledo, I sat in complete boredom in the hotel.

We had an incredibly beautiful trip straight to Chabua the next day. The atmosphere was delightfully clear and we flew close to the Himalayas all the way. Since it was “winter,” the snow on the range was gorgeous. Two brass hats and I had an argument about which of the peaks was Everest. I pointed out Everest’s “cocked hat” and beautiful Kinchinjunga as well, but the colonel said, “That isn’t Everest. The pilot says we won’t see Everest for another hour.”

I bit my tongue. Of all lessons I’d learned in the army, the chief was that one does not deny the truth of anything an officer says, no matter how wrong it may be, if that officer happens to be your senior even by a day. I continued to enjoy looking at Everest and Kinchinjunga by myself, recalling the happy days, ten years before, when our whole family had made a four-day march from Darjeeling, opposite the base of Kinchinjunga, to Sandakphu, almost on Kinchinjunga’s shoulder, just to have a good look at Everest. One doesn’t forget things like that.

The colonel, poor chap, never did see Everest.

We landed at Chabua early in the evening. No transportation was available to Ledo till morning so we spent the night there and I hopped a ride in General Wheeler’s car next morning. The portents were good. I knew my travels had really begun when I noticed that I had left my pillow behind in Chabua. I always leave something behind at each stop when I am on a long journey.

At Ledo I found my friend Lieutenant-Colonel Victor Haas who once told me in Lashio that no matter how good a teacher I was I would never make a decent nurse out of a Kachin.

Later Haas came to Ramgarh to visit me. “When I was flown out to India,” he said on that occasion, “they asked me what famous historical sights I intended to visit and I told them there were only two famous things I wanted to see in India: the Taj Mahal and Seagrave’s Burmese nurses. Now let’s see them!” At the end of the inspection Haas had to admit that Kachins could be made into wonderful nurses.

Haas was now surgeon of S.O.S. in Ledo. He not only secured my instruments for me but drove me to “Hellgate” in sight of the Pangsau Pass and then back to my assigned quarters at Chih-Hui-Pu. To my delight one of our unit’s best friends, Lieutenant-Colonel McNally, was in command. Mac was in perfect condition, griping in his best manner at what was going to happen to his Chinese troops when they established their advance screen in the Naga Hills.

“It’s ghastly country, littered with the bones of the refugees,” he said. “There is malaria everywhere and the streams must be still swarming with the cholera, typhoid, and dysentery that killed the refugees by the thousands. In two weeks I have to send Chinese troops down to Tagap and Punyang and there isn’t a medic around to go with them.”

“There’s me,” I said, ungrammatically.

“If I had a chance to see General Stilwell I’d jolly well ask for you. But what would happen to Ramgarh?”

“My executive officer, Major Crew, is a better army officer than I’ll ever be,” I said. “Besides, there are only about seven hundred patients left in Ramgarh instead of twelve hundred. They could spare a couple of surgical teams from our unit and never miss us, and” I added out of the corner of my mouth, “General Stilwell is in Chabua. I rode up in his plane.”

Colonel McNally jumped up and reached for his hat. A few seconds later his jeep vanished around the corner.

Chabua had only one plane out the next day and it was bound for Delhi after one stop in eastern Bengal. I had either to get out at the Bengal field and chance catching a plane for a thirty-six-hour ride to Ramgarh through Calcutta or fly on to Delhi, catch another plane back to Gaya, and thence the short way by train to Ramgarh. I chose the latter as the quickest route.

Back at Ramgarh Lieutenant Harris and Stinky Davis wanted to go along if my Ledo coup produced results. It did. General Stilwell radioed orders for two surgical teams of the Seagrave Unit to report to Ledo for orders.

Major Grindlay and I had a quarrel as to whether he or I should lead the party. At last he agreed that I should go—if I would promise to use all my influence to move him and the rest of the unit out into Burma as soon as possible. I was in a humor to promise him the moon.

Captain Webb headed the smaller group—Stinky, four nurses, and my Lahu boy Aishuri—while Lieutenant Harris and I led the larger group of twelve nurses and Judson, my Burmese supply officer. I discussed the question of Chinese orderlies with General Boatner, and he ordered me to select thirty Chinese sailors and soldiers from our wards and take them along. These sailors had had a hard life. Removed months before from interned ships at Calcutta, they had been a constant headache to the British who gladly dumped them in the lap of the Chinese Army when it reached Ramgarh. The Chinese could think of nothing to do with them except put them in a concentration camp, where they became an American headache. General Boatner cured the headache by turning them over to me to use as orderlies and cooks in the hospital. Having spent their lives on occidental ships, they were the perfect servants.

“But, General,” I said, “what if they desert as we pass through Calcutta?”

“You won’t be held responsible,” he replied.

The thirty men—there were six soldiers among them—were suspiciously eager to go with us.

The railways were, as usual, overloaded. We might have two compartments but no more, so General Boatner ordered me to leave at once with my larger group, while Captain Webb and his group were to follow with the Chinese on the next available train.

On the seventeenth of March, we were at the great jumping-off place for Stilwell’s return to Burma—Ledo. We parked the girls at the 20th General Hospital and took up our quarters in a tent at Chih-Hui-Pu. That afternoon some of the girls turned up, their eyes popping.

“You know those American nurses?” they said. “They aren’t a bit ashamed of each other. Why, when they bathe they strip to the skin right in the middle of their barracks and even bathe in front of each other!”

In the excitement of moving I was sure the nurses had forgotten my birthday, but at five next morning the entire Chih-Hui-Pu staff, Chinese and American, was astounded to hear “Happy Birthday to You” pour from female throats right in the middle of a male camp. The girls had carried presents for me all the way from Ramgarh. Later I learned that the girls in Ramgarh had also thrown a party in honor of my birthday.

That afternoon, as we were repacking our equipment into forty-pound porter loads, Colonel McNally asked me to take a look at Colonel Rothwell Brown of the tanks who had just returned from a trip to Shingbwiyang in the Hukawng Valley with my former Burmese supply officer Tun Shein. They had been lost for seven days trying to find a road which the maps insisted ran from Taga Sakan to Hkalak. Rothwell Brown is an extremely efficient artist at profanity and he was at his best as he described how their rations had run out and Tun Shein had kept them both alive on roots, leaves, and ferns. “Ferns,” he profanely insisted, “are the best three-blank things to eat I ever tasted.”

The climax of their trip had come when, at the foot of the incredible climb up to Ngalang, Brown had come down with a terrific chill and a temperature of 106°. But he marched on into Ngalang, 106° and all. Now a shadow of his former self, he was worrying Mac to death insisting that I treat his malaria “on the hoof.”

McNally asked Colonel Tate of the colored engineers to get me a hundred porters for our trip. The colonel claimed it couldn’t be done, and then promptly went ahead and did it. Stilwell and his men only enjoyed life when they were doing the impossible. So Mac put us all into two Chinese six by six trucks and started us off for Hellgate where the porters would be waiting for us.

How the girls enjoyed the trip! They gurgled with laughter at the signs the colored engineers had stuck up along their “Ledo-Tokyo Road”: “DON’T TEAR ME UP, ROLL ME DOWN!” “I’M YOUR BEST FRIEND; DON’T RUIN ME!” “HEADQUARTERS FIRST BATTALION, HAIRY EARS.” “TATE DAM. HOT DAMN, WHAT A DAM!” And later, “WELCOME TO BURMA. THIS WAY TO TOKYO!”

Soon we began to pass groups of colored boys at work. One stepped back wearily with his spade, took one look at us, threw his hat in the air, and screamed, “My God! WOMEN!” The girls became a bit scared as they recalled some of the things they had heard about the way American Negroes treat women. They recovered soon enough as they became acquainted at close hand with our colored soldiers. Let me say here, for the record, that though an occasional American white enlisted man or officer and an occasional Chinese soldier or officer had been known to offer insult to our Burmese nurses, not one single colored soldier ever treated them with anything but respect. The girls often recalled with misty eyes the colored soldiers they came to know so well.

When we reached Hellgate—Chinese drivers were not permitted to go farther—we expected to sleep in some of the coolie huts. But Colonel Tate had sent word to the captain of engineers that we were coming, and the captain met us and escorted us to his own camp, where he turned over the newly completed messhall to the nurses and gave me General Wheeler’s bed—the only time I ever had the honor to sleep in a major general’s bed. I begged the captain to let the girls cook their own Burmese food since they were so fed up with American meals, and much against his sense of hospitality he permitted them to do so. It was the first time the girls had cooked for themselves for many months and the dinner was delicious.

We were a day ahead of schedule so the next day the girls asked to go for a swim. There were Americans, Chinese, and Garos bathing under the Hellgate bridge and the girls refused to bathe there. I led them two miles down the Refugee Trail, where we found a deep hole near a village of aborigines garbed in loincloths. We had a delightful swim, in spite of the fact that we had had to step over a few whitened refugee skulls to get there, and then rushed back to camp to beat the rainstorm that invariably arrived when our unit was about to travel somewhere.

The next morning some colored boys drove us up the mountain until they bogged down in the mud just before reaching the Pangsau Pass. We had been surprised at how good our Chinese drivers had been after their Ramgarh training—we remembered well how they had driven on the Burma Road! But these colored boys could really drive. Even when the fresh earth of the road shoulders slid away they performed miracles getting their trucks back onto solid ground again. We stepped out into the deep mud, when the trucks finally bogged down, and began to march. Almost immediately Sein Bwint’s flimsy shoe was sucked off in the mud. We hadn’t been able to buy one pair of stout shoes in all India that would fit the girls, and G.I. shoes, three sizes too large, were so ungainly that I never dreamed the girls could use them. Captain Webb, however, thought differently, and the girls clattered around delightedly all day long in their huge oversize G.I. shoes.

As we passed the “WELCOME TO BURMA” sign at the top of the pass the girls began to laugh and sing and trot downhill, though the rain was drenching and cold. They were on their way now, back to Burma and home and parents. That night we slept, still drenched, in three little huts in Nawngyang—the returning refugees’ first night in Burma! To our astonishment we were serenaded. “Silent Night,” “The Spacious Firmament,” “All Hail the Power,” and other favorite hymns swelled forth in exquisite harmony...

Table of contents

- Title page

- TABLE OF CONTENTS

- DEDICATION

- ILLUSTRATIONS

- MAPS

- PUBLISHER’S FOREWORD

- PART ONE-RAMGARH TO THE NAGA HILLS

- PART TWO-THE LONG ROAD TO MYITKYINA

- PART THREE-RETURN TO NAMKHAM

- REQUEST FROM THE PUBLISHER

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Burma Surgeon Returns by Dr. Gordon S. Seagrave in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & European History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.