- 140 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

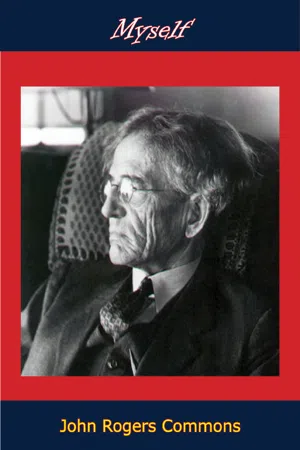

Myself

About this book

John R. Commons (1862-1945) was one of the most significant figures in the development of American economics, both owing to his economic thought and his impact on practical affairs. He began as an avid follower of the Social Gospel, committed to a program of economic and political reform, and later in his career he became the foremost authority on American labor unions. One of the founders of the Institutional school, Commons developed theories of the evolution of capitalism and of institutional change which continue to influence modern economics.

The present volume, which was first published in 1934, is his autobiography. In it, Commons classifies himself as both a pragmatist and a Progressive. He collaborated closely with Wisconsin's governor and U.S. senator Robert La Follette, Sr., until 1917, when he opposed La Follette's anti-war position. He drafted innovative legislation on issues such as civil service reform, worker's compensation, and utility regulation. He championed improved safety standards and unemployment benefits for workers, believing that financial support for them should come from corporations. He also advocated government mediation among industry, labor, and other competing interest groups. In the 1920s, Commons' legislative initiatives on social welfare and federal economic coordination anticipated New Deal legislation. Commons also exerted long- term influence through his students, many of whom went on to occupy key academic, research, and policy positions. Today, he is remembered chiefly as the founder of modern American labor history.

The present volume, which was first published in 1934, is his autobiography. In it, Commons classifies himself as both a pragmatist and a Progressive. He collaborated closely with Wisconsin's governor and U.S. senator Robert La Follette, Sr., until 1917, when he opposed La Follette's anti-war position. He drafted innovative legislation on issues such as civil service reform, worker's compensation, and utility regulation. He championed improved safety standards and unemployment benefits for workers, believing that financial support for them should come from corporations. He also advocated government mediation among industry, labor, and other competing interest groups. In the 1920s, Commons' legislative initiatives on social welfare and federal economic coordination anticipated New Deal legislation. Commons also exerted long- term influence through his students, many of whom went on to occupy key academic, research, and policy positions. Today, he is remembered chiefly as the founder of modern American labor history.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

V—WISCONSIN

I WAS born again when I entered Wisconsin, after five years of incubation. I came at the time of the University Commencement, in 1904, and heard the new President, Charles R. Van Hise, risen from the Geology Department, tell the faculty, in his inaugural address, that each teacher was expected to get proportionate credit for Instruction, Research, and Extension.

Now, in thirty years, I see it accomplished. During my semi-retirement, my former and present generations of students come vividly before me; I review my Friday Niters; I recount my pieces of research and administration; I listen to “WHA, the Wisconsin state-owned station,” which broadcasts “The College of the Air.” I hear the University, or the State Departments, talking to the boys and girls on the free instruction open to them from childhood to the post-graduate and professional degrees; telling all the people of our citizenship, our highways, our forests, our three thousand lakes, our unemployment, mortgages and prices. There is Jennie Turner, now with a State Department—she is for me Jennie McMullin, my Irish girl of years ago—telling them of vocational education, of the State Library that will loan books to study classes, without charge; telling them of beautifying their homes and roads. There are the University professors telling them of electricity, chemistry, the social sciences, music, and other researches and teachings of the University. It is President Van Hise’s instruction, research, extension.

I came too, in 1904, at the time of another commencement held in the same University building. It was the last Republican State Convention preceding the new system of primary elections. It gave to Robert M. La Follette, after two terms as governor, control of both branches of the legislature. The socialists of the factory system of Milwaukee and the shore of Lake Michigan had been organized in 1898, led by Victor Berger, from Austria. The small farmers and the younger generation of professional and business men had been organizing since 1894, led by La Follette. His French family came from across the Appalachian Mountains, but he came from a small farm where they settled in Wisconsin. The big business and the financiers from New York, who previously had dominated the Republican Conventions, were led by Emanuel Philipp, afterwards governor of the state during the World War. His family came from an Italian Canton of Switzerland, but he, like La Follette, came from a small farm in Wisconsin. I saw, from the platform, these two alignments split the Republican party. The next day the followers of Philipp held their own convention. The Democrats were a split minority and lined up with the Republican split, except for a skeleton organization of professionals, during the forty years 1894 to 1934. The three groups were Progressives, Conservatives and Socialists, each with representatives in the state legislature. The issues were no longer political—they were economic. I made, during these thirty years, Conflict of Interests, not the Harmony of Interests of the classical and hedonistic economists, the starting point of Institutional Economics.

My new birth, in 1904, thrust me into this conflict. Wisconsin, with two and a half million people, has been a miniature for me of one and a half billion people around the world, driving on to Communism, Fascism, Nazism. The State University and the State Government, only a mile apart in a small city, have been a focus, unique among the states, for instruction, research, extension, economics, class conflict, and politics.

I had met La Follette as governor in 1902, on my taxation trip for the National Civic Federation. He was then bringing to Wisconsin the new system of ad valorem taxation which originated in my own Indiana when I was there some seven years before. This system based the taxation of railways and other public utility corporations, not on the older ideas of corporeal property located in the state, but on the newer idea of the state’s share in the total value of the “intangible property” of the corporation as a unit throughout the United States, evidenced partly by the sale-value of its securities on the New York stock market. I had known the editor of the Indianapolis News, who drafted the Indiana law. He had explained to me, in 1895, the principle of the new system of taxation, afterwards sustained by the United States Supreme Court in a case coming up from Ohio. I had not then seen its significance. But now, seeing the intense political conflict to Wisconsin over this same economic issue, I got my first idea of a “going concern” existing wherever it does business, distinguished from a “corporation” existing only in the state of its incorporation. In the course of the next thirty years I worked out the idea of going concerns as existing in their transactions of conflict, interdependence and order.

La Follette had been a member of Congress from the Madison district, as early as 1884, serving on the Ways and Means Committee under its chairman, William McKinley. There he had won approval of the Republicans by his speeches supporting, with new arguments, the tariff and the tax on oleomargarine. But in 1894 he resented the control of the Party in Wisconsin by the financiers, and started on his ten-year campaign to wrest that control from them. Afterwards, middle-aged men, now opposed to La Follette, have told me of the inspiring effect La Follette had on them in this ten-year campaign when they were younger. He opened up to them a noble idea of patriotism for the state, wherein there should be no corruption in politics, no control of governors and legislatures by the lobbyists of corporations, no “machine” politics controlling the party conventions. Instead there would be a resurrection of the early American idealism of government by the people themselves.

I began to learn from this a new “economic” interpretation of history and class struggle to take the place of the Marxian “materialistic” interpretation. As long as La Follette’s inspiring patriotism was working along the lines desired by an economic class, they supported him. But after he had written into legislation what they wanted they deserted him and went over to the conservatives. First, small business men and much of the great lumber interest of the state supported him in his attack on the railway corporations to obtain equality of taxation and control of rates which interested them as shippers. When these objects were attained they went over to the opposition. La Follette relied upon them at first. By far the wealthiest lumber man of the state, Isaac Stephenson, bought a daily paper in Milwaukee in order to have at least one metropolitan daily for the extension of the new ideas of taxation and freight-rate control. La Follette stood loyally by him, and succeeded, in the legislature of 1907, in overcoming opposition among his own followers and electing Stephenson to the United States Senate. Afterwards he said to me, in the Senate lunch room at Washington as Stephenson was passing by, “They are getting him.”

La Follette was stigmatized by his opponents as a “boss.” But I could never see it that way. I had known, at close contact, the Tammany boss system in New York. I began to analyze the difference between a boss and a leader. The boss controlled the jobs—the means of livelihood of his followers—through a hierarchy of district bosses down to the rank and file of the voters. The “boss” could not himself be elected to a public office. He was merely the head man in a private association of these actual and would-be bosses. By this economic control of subordinates he named and elected the public officials and obtained funds from the financiers who wanted franchises or other special privileges. La Follette had shown by his organizing ability and the most determined willpower that I have known, that he had all of the qualifications needed by a boss. But, at the high point of his success in gaining control, in 1904, of the convention and the Republican organization—also a private association—he deliberately deprived himself of the instruments of bossism. He had induced the people to approve direct primary nominations of public officials, thus doing away with the convention system.

Afterwards I saw how it worked. To the legislature came a Democratic single-taxer for whom I drafted a bill on that subject, Edward Nordman, a pioneer farmer from the North Woods, not endorsed by any political party. His campaigns were merely postal-card campaigns, stating his single-tax principles directly to the individual voters of his county.

I saw again how it worked against La Follette himself. Irvine L. Lenroot, of Swedish descent, was his leading lieutenant, chairman of the convention in 1904, and Speaker of the Assembly in the notable sessions of 1903 and 1905. In the preceding campaign of 1904 La Follette, through his control of the convention, had nominated and elected a Scandinavian immigrant, James Davidson, as lieutenant governor on the same ticket with himself as governor. Here La Follette was admittedly a boss. But Davidson, when he became governor, after La Follette resigned to go to the United States Senate, turned out to be a conservative, lining up with that wing of the party. La Follette determined to have Lenroot nominated in the primaries of 1906 against Davidson, the conservative candidate. He made a marvellous campaign, with large and enthusiastic audiences, through the state, in favor of Lenroot. When he made his last speech, on the night before the primaries in the University gymnasium, to a crowded enthusiastic audience, he was beaming with excitement. He said to me on the platform that, judging by his meetings, Lenroot would be nominated by 50,000 majority. But the next day Lenroot was defeated by a large majority. La Follette had mistaken enthusiasm for himself for enthusiasm for Lenroot.

So there was driven home to me the difference between a leader and a boss. After studying the decisions of courts on economic disputes, I made the difference rest on the legal-economic distinction between persuasion and coercion. The boss controls by economic coercion, the leader controls by persuasion. La Follette had nominated Davidson, and was a boss. La Follette by persuasion could not nominate Lenroot against Davidson, and was merely a leader. The people of Wisconsin, under his leadership, would no longer stand for bossism, but they were eager for leadership. La Follette, at his climax of political power, had reduced himself from boss to leader.

Another demonstration of his abdication from bossism had come even more vividly to me in my first six months at Madison. La Follette had not, as far as I know, made a single reference, in his campaign of 1904, to civil service reform. After the November election, when he was undisputed boss, he asked me to draft the best civil service law to be derived from a study of all similar laws in the country. He made only one stipulation. All existing employees of the state, except the heads of departments and elected officials, were to take the same civil service examinations as others, to determine whether they were competent to carry on efficiently the work for which they had been appointed. This included his own appointees during his preceding governorship of four years. I mildly explained that it had never been done. Always the distinguished civil service reformers, like Grover Cleveland, had “blanketed in” the existing appointees. La Follette’s plan was a desertion from his own followers who got public service jobs by working for him. He did not argue with me. He simply replied that was the way he wanted it. He abdicated bossism.

It was charged in the state that this provision of the act was mere bluff. La Follette’s own appointees would not be removed for inefficiency by a Commission appointed by himself. I never followed it up to see what happened. I only know that he asked me to become one of his first board of three commissioners. I had come from another state and had not “worked” for him. I could not accept, and he appointed a professor from the Department of Political Science.

A curious outcome, for me, of his civil service law, occurred six years later, when I was promoting before legislative committees the adoption of the Industrial Commission law which my students and I had drafted with the approval of the Progressive leaders. I found myself in direct opposition to the civil service law which I had drafted six years before. A clause in the proposed law exempted from civil service examination the “deputies” (of the Industrial Commission. But La Follette’s principles had percolated through his followers, and in the legislature they exclaimed that they wanted no “pets” in this new Commission. They struck out the exemption.

After I was appointed to that Commission for the short term of two years by Governor Francis E. McGovern, my colleagues and I—Charles Crownhart, previously chairman of the Republican State Committee and afterwards Justice on the Supreme Court of the state; and Joseph E. Beck, previously Commissioner of Labor and afterwards member of Congress and then member of the State Agricultural and Market Commission—visited the State Civil Service Commission. We explained to them what we needed in the qualifications of our deputies. We needed especially the qualification of mediators and conciliators between the conflicting employers and employees of the state, as well as deputies capable of taking testimony and making investigations that would stand the scrutiny of the courts. We proposed that the civil service examinations should be “elimination contests,” but that the actual appointments for the positions should be made on oral examinations and recommendations by the advisory committee of organized employers and organized labor which were authorized by the new law and which we had already begun to set up. This proposal was not contradictory to any of the civil service laws as I had studied them. The Civil Service Commission accepted the proposal, with certain safeguards. Several satisfactory deputies were appointed to these responsible positions. The employers’ representatives even selected two socialists, William M. Leiserson and Fred H. King, to have charge of the Milwaukee State Employment office, and a trade unionist, Stewart Scrimshaw, to administer the new apprenticeship law.

I was glad that I had been defeated by the devotion to civil service rules which La Follette had succeeded in bringing home to his followers. It relieved us of all political pressure from Progressives for jobs and gained for the Commission the confidence of employers to whom we were supposed to be antagonistic. It was this new kind of civil service, having the confidence of capital and labor, that made possible, twenty years afterwards, the enactment of an unemployment insurance law entrusted to the Industrial Commission for its administration through a similar advisory committee of organized employers and organized employees. We had discovered in 1911 what La Follette had known in 1904, that progressive legislation could not be made enduring and constitutional before the courts—and, in our case, conciliatory toward organized employers and employees—except by a civil service law in which the Progressives, like their great leader, denied themselves political preference for jobs.

Λ stunning illustration came to us in the Milwaukee employment office. The Industrial Commission law had given power to the commission to remove existing officials and to appoint others in their places. We removed the head of the Milwaukee office, a political appointee, and, as stated above, named two socialists in his place on the recommendation of our advisory committee of employers and trade unionists. Shortly after, the Progressive governor of the state, who had appointed us, came to us with the alarm that a delegation of eminent citizens, including a judge of a Milwaukee court, had protested to him against this amazing concession to what they argued was the hot-bed of socialism in Milwaukee. Our chairman, Mr. Crownhart, proposed a solution. Let the governor invite his delegation of political supporters to meet in Milwaukee with the employer members of our advisory committee who had joined in recommending to us the appointments. The meeting was held. We learned afterwards of the drubbing which the employers gave to their political fellow citizens. The political incumbent, they said, had been running merely a loafing place for “heelers,” and the employers could not take on anybody sent to them for jobs. Indeed, they had been forced to set up a private “citizens’” employment office, alongside the state office, in order to find jobs for the competent unemployed. These two socialists were already operating that office and sending to the employers the kind of applicants they needed in their shops. The socialists and trade unionists thus appointed had been graduate students of mine, and naturally neither I nor my colleagues on the Commission took any part in the conferences or oral examinations. We were simply able to point out, to anybody who objected, that the parties most directly concerned—organized capital and organized labor—had really made the appointments and would appoint their successors.

As I look back over my thirty years in Wisconsin and recall the many attempts, including my own in 1911 to emasculate the civil service law, I conclude that the greatest service La Follette rendered to the people of the state was that civil service law of 1905. Without that law, and the protection which it gave to him and succeeding governors in making appointments, his own administrative commissions on taxation and railway regulation would soon have broken down. The state, in thirty years, has switched from Progressives to Conservatives and back to Progressives and then to Democrats, and these shifts have always brought open or covert attacks on the civil service law. Without the civil service law, none of the later so-called “progressive” laws involving investigation and administration could have been enacted. Their enactment depended on confidence, on the part of the strenuously conflicting economic interests, in the public officials to whom the administration of the laws should be entrusted.

1 sometimes have heard from people of other states that the Wisconsin pioneer success in administering progressive legislation must have come from the large German element in the state who brought with them the traditions of the efficient government of Germany. But the Germans in Wisconsin, although exceeding in numbers any other of its many nationalities, have been the least active, politically, of all. The civil service law was sprung on the state by one man, La Follette.

I now see that all of my devices and recommendations for legislation in the state or nation have turned on this assumption of a non-partisan administration by specially qualified appointees. When I made my report for the Industrial Relations Commission in 1915, the report was attacked, in and out of the Commission, on the ground of “bureaucracy” and government of the lives of the people by “experts” instead of government by “the people” themselves. Germany was pointed to. It was said that I wanted to create political jobs for “intellectuals” like myself. Now that the Democratic politicians, after thirty years of taking their hopeless chances in getting a preference in Wisconsin, by nullifying the civil service examinations, on account of their work for the party, have openly avowed the tradition from Andrew Jackson and William Jennings Bryan, that a good Democrat is as good as or better than anybody who passes a civil service examination, I give up, after seventy years of age, and wonder whether I have been wrong all along. Although a good Democrat myself I am glad that I am retired and can sit at my window cogitating about my philosophy of scarcity and conflict. Through it all, I go back to La Follette’s instruction to me in 1905, and to my later conclusions when I made Administration more important than Legislation. Legislation furnished the authorizations. Administration was legislation in action.

In my civil service bill-drafting of 1905 I made another discovery. It was Charles McCarthy. In his particular field he was as distinct a personality and pioneer as were La Follette and Berger in the political field. His versatility, ingenuit...

Table of contents

- Title page

- TABLE OF CONTENTS

- ILLUSTRATIONS

- I-TO MY “FRIDAY NITERS”

- II-NORTH AND SOUTH

- III-GRADUATE AND TEACHER

- IV-FIVE YEARS

- V-WISCONSIN

- REQUEST FROM THE PUBLISHER

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Myself by John Rogers Commons in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & American Civil War History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.