![]()

PART ONE

COLLECTORS AND THE PARALLELS

![]()

The instinct that leads men to collect and preserve things of beauty, value, or interest is as old as the race itself and expresses itself in many ways. Some collect early parchments or ancient carvings; many more acquire old books or paintings. The variety is infinite, but by far the largest groups are those who collect coins and stamps. The newer and much more limited fraternity collects fire marks.

To the uninitiated, collecting is merely a hobby. In actual fact, however, it is much more than that, inasmuch as collectors are the real historians. Their medium is the stuff of which history is made, and their efforts have preserved down to this day the creations of the passing ages which would otherwise have been lost forever. Thousands, through collecting, have become experts and genuine antiquarians; many have made important contributions to history since in their zeal they are constantly turning up the previously undiscovered or unrecorded item. When the sum of these findings has been assimilated and coordinated into a definite picture the result is a new facet, a new known fact of history. Historians have followed this very procedure for centuries.

Collectors and other students of history are well aware of the fact that in reality there is little or nothing new under the sun, almost no situation that has not had a multitude of parallels in the past. Creative minds either knowingly or subconsciously draw upon the past almost every waking moment, molding and recreating it to fit a particular purpose. Without the many who seek knowledge of the past, both literary and material, even those who are content to live in the world of the moment would find themselves severely handicapped. Great advances in every field of endeavor have been based upon the sum of previous discoveries. This is the background, the powerful drive that motivates the true collector. His searching mind and ceaseless devotion result in many unselfish contributions to society.

In certain basic respects, many of the numerous hobbies which develop history are closely related. To outline more clearly the underlying principles of the acquisition, selection, and perpetuation of the marks of assurance, we shall, in Part One, draw parallels with similar situations in the better-known fields of coin and stamp collecting.

Coin collecting, or numismatics, is the oldest of the three activities. “Numismatist” is derived from the French numismatique (current coin—to have in use). A reference in 1799 describes a numismatist as “one who has a special interest in collecting coins.”

Next, in point of age, come fire marks, or signs of insurance, which were variously known as “badges,” “placques,” and “house signs.” Small collections of these were first made by certain fire insurance companies in the early nineteenth century. To this activity has been designated the term “signeviery” (from the Old French signe, denoting signs, as attached to buildings, and vier, the Flemish root from which our Anglo-Saxon word fire is derived). Thus, a collector of fire marks is a “signevierist.”

Because postage stamps were not used until Great Britain issued the “Penny Black” on May 6, 1840, stamp collecting becomes the last of the three parallel endeavors. In 1864, M. Herkon, a postage stamp collector, proposed that the word “philatelist,” derived from two Greek words (philos, loving, and atelia, exemption from tax), be used to denote a collector of stamps.

And, so, hereafter we will frequently refer to the three parallel designations: numismatics, signeviery, and philately.

We have observed that there are recognizable parallels among the coin, the stamp, and the fire mark as collector’s items. Such parallels are evident in the history of each, for all were created to fill a specific need and perform a useful function.

1. THE COIN

From the earliest periods of history there are references to barter and trade among the first of the earth’s citizens. Thus one can well imagine the exchange of a stone axe for a mortar and pestle in which could be ground the coarse grains of the age. In each of the ancient lands we find that some type of money, developing through an almost endless chain of materials, was used as a medium of exchange. In Angola in ancient Africa a flat, paddle-shaped piece of iron, twelve pieces of which bought a wife, was used. Egypt produced glass ring money, while Ethiopia favored its native ivory. Ancient China used jade, while the Incas, who had advanced far in the arts and culture of the early Americas, used gold, silver, and copper. As man evolved in his associations with other men he experienced the need to acquire by exchange items of unequal or varied value possessed by others.

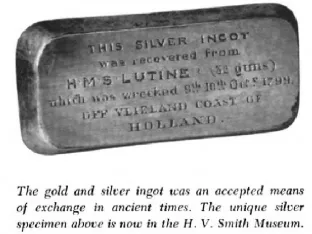

Numismatists and archaeologists have unearthed many unusual specimens of ancient moneys. Their discoveries include shells, bone, wood, stone, and odd mineral specimens which frequently took the form of implements, weapons, or ornaments. Later, the widely accepted means of exchange assumed the form of ingots or bars of precious and useful metals, usually gold, silver, or bronze. As the population grew and travel among the peoples and nations spread, the need of a more convenient method of barter developed. The forerunner of the modern coin was brought into existence by the early mintage of silver, gold, and bronze undertaken by the Greeks, the Persians, and finally the Romans. Since that time there has been a constant succession of improvement in mintage and international exchange.

2. THE STAMP

In the first days of postal service, it was customary for the recipient, if he finally received the item, to pay the postage. Great Britain inaugurated the first prepaid postage system on May 6, 1840, when they issued the “Penny Black” stamp. The stamp was little different from those issued today and contained the likeness of Queen Victoria. At first there was considerable resentment over the prepaid postage system, and many British folk objected to “kissing the back of Queen Victoria’s face.” Resistance soon faded, however, as the value of the postage system was recognized. In 1842 the practice spread to America where a local “carrier stamp” was issued in New York City. Switzerland and Brazil followed in 1843. With other local issues in the interim, the first United States government general issue stamp was placed on sale in 1847. In the same year the small island of Mauritius, located on the main route from Britain to the East Indies, issued its first stamp. Now, practically every country in the world subscribes as a member to the regulations of the International Postal Union, and one can forward mail to the farthest point on the globe without difficulty.

3. THE FIRE MARK

Just as the coinage and postal systems evolved from crude beginnings, so, too, assurance of security from loss by fire has also run the gamut. Indemnity from loss by fire dates back more than twenty-five hundred years when “communes” of the towns and districts of Assyria were formed. After many incidental trials and tribulations, insurance finally reached a more refined status lute in the seventeenth century when it, too, developed its own symbol of exchange and security.

Raging and destructive fires have rent the hearts of mankind since the first stirrings of civilization. There are many references to conflagrations during Biblical times, and the burning of Rome is a story familiar to most readers. The greatest holocaust of more recent centuries, however, was that which devastated London in 1666 A.D. At that time, methods of extinguishment and control were either unheard of or so rudimentary as to be of little help. Consequently, the fire swept unchecked through the city.

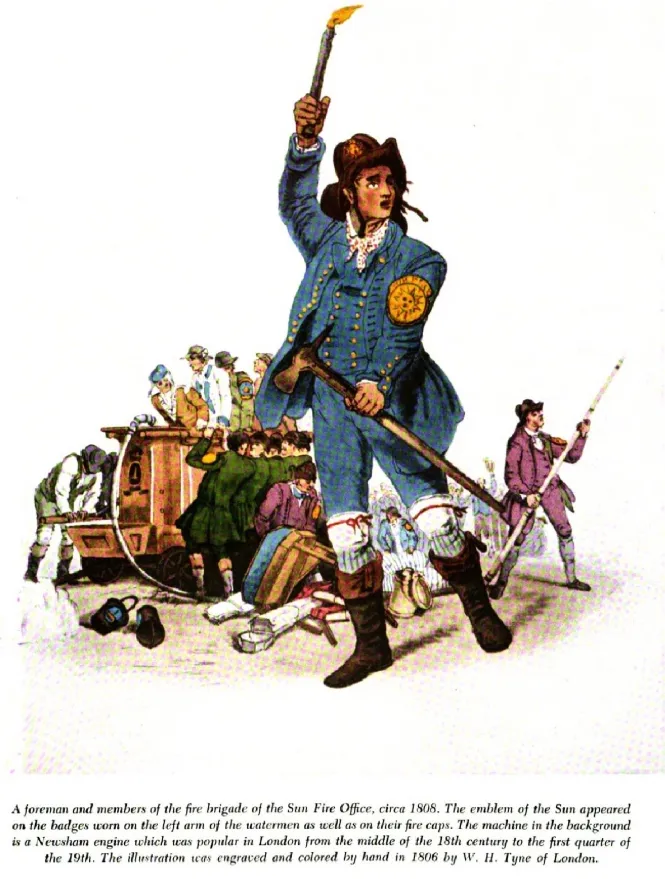

The work of rebuilding progressed during the following year, and we learn from the archives of the British Museum that in 1667 the citizens and officials of London finally gave serious thought to fire protection. The City and Liberties were divided into four parts and each of them was to provide eight hundred leather buckets. Every parish was to have two hand squirts of brass, a number of “pickax-sledges,” and “shod shovels.” Each quarter of the city was also to have fifty assorted ladders, and every householder was to provide buckets and be in readiness to pass them from hand to hand at the scene of the fire. Some sort of a fire-fighting organization had been established, for there is a reference to fire commissioners, engineers, and sentinels. History records that a fire insurance association, known as the Feuer Casse, had been established in Hamburg, Germany, in 1591, but no such plan or fire indemnity system was developed in England until 1667. In that year Dr. Nicholas Barbon organized the first recorded fire insurance scheme for insuring houses and buildings. The venture was known as The Fire Office. Even during the first year of its existence this office maintained a number of watermen with livery and badges. In 1683, The Friendly Society organized its own brigade, and in 1699 the Hand-in-Hand Fire and Life Insurance Society took similar action. The individual offices had their names prominently displayed on their engines which were painted a distinctive color and when the several brigades were proceeding to a fire they must have made quite an attractive picture. It is understood, of course, that these brigades were not formed for the protection of the public at large or for the mutual protection of the offices. For instance, if the brigade of office “A” arrived at the scene of a fire and found that the property was insured by office “B,” it promptly returned home or merely staved to watch the fire as a more or less disinterested spectator. At least this appears to have been the rule with the majority of offices.

It is obvious that when the fire brigade crews of all the different offices turned out at the alarm of fire and arrived at the scene of action, there had to be some means of revealing instantly whether the property was insured or not and, if insured, which office held the risk. The several offices, therefore, devised a metal sign which they fixed on the front of the property in which they were interested. In other words, these signs “marked” the property and are the signs which we know today as “fire marks.” The fire mark was not originally evolved solely for the purpose of marking the property insured for the guidance of the office fire brigade, however. It was also necessary because the original offices made it a condition that no property was “secure” until the mark had actually been fixed thereon.

From the early proposals of The Fire Office we learn that they used as their device the emblem of the phoenix. Because of the popular acceptance of this mark, the company adopted the name Phoenix in 1705 (this is not to be confused with the Phoenix of today, however, which was established in 1782).

There are many early references to the origin of the practice of affixing fire marks to insured buildings by British companies, and some of these will be referred to in later chapters.

A majority of the fire insurance offices established in London before 1833 organized their own brigades, but in that year they formed a single joint brigade for the whole of the city. This brigade was known as the London Fire Engine Establishment. As a result of a conflagration in 1861 there was enacted the Metropolitan Fire Brigade Act of 1865, a public authority established in the city to assume the responsibility for fire fighting. In 1866, all the private brigades’ equipment was turned over to the Metropolitan Brigade by the insurance companies. Company-owned brigades lingered elsewhere in Britain until at least 1925. It is therefore apparent that the transition from the company-owned brigades to the municipal department was a gradual one consuming almost a century in passing.

It is generally conceded by collectors in Great Britain that the true fire mark passed when the brigades became a public responsibility. Subsequent to that time many collectors refer to the signs issued largely for advertising purposes as “plates.” To a signevierist, however, they definitely pertain to an era in the progress of assurance and can well be admitted to the general classification of a fire mark.

Besides Great Britain and America, the fire mark was also used in many other countries for the same purposes as it was employed in these two areas. Probably a greater portion of the marks of other countries was used for advertising purposes, or to give assurance to the policyholder. Each of these countries or areas will be referred to in detail in the closing chapters of this book.

In America, the relationship between fire insurance concerns and brigades was the reverse of that established overseas. Almost as soon as the white man settled upon the eastern seaboard volunteer fire brigades were formed. From 1648 these volunteers operated as bucket brigades, but in 1731 New York received its first hand pumper from London. The number of volunteer brigades, with their many rivalries, spread throughout the larger centers of population very rapidly, and these organizations often had as their members the political and social leaders of the Community.

The volunteer firemen were mostly responsible for the organization and establishment of the first fire insurance companies in America. While the first and somewhat short-lived fire insurance scheme was born in Charleston, South Carolina, the origin and use of the American fire mark is attributed to the next company of record which was organized at Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, On April 13, 1752, and known as the Philadelphia Contributionship for the Insurance of Houses from Loss by Fire. It is stated that at their meeting of May 20, 1752, a committee was to treat with John Stow about making the marks for insured houses. On July 22 an order was drawn on the Treasurer to pay John Stow the sum of twelve pounds, ten shillings for one hundred marks. It would, therefore, appear that the use of American fire marks began in the year 1752, a custom outlined in an excerpt from their minutes of October 3, 1755, wherein it is related that the Directors “...proceed to view the house of Edward Shippen in Walnut Street, No. 103, that was damaged by means of a fire which happen’d at the house of William Hodge, situate in that neighborhood; which house of E. Shippen having no badge put up. The Directors observing that much of the damage was done thro’ indiscretion, which they think might have been prevented had it appear’d by the Badge being placed up to notify that the house was so immediately under their care; to prevent the like mischief for the future; it is now ordered that the clerk shall go round and examine who have not yet put up their Badges; and inform those that they are requested to fix them immediately, as the major part of the Contributors have done, or pay Nathaniel Goforth and William Rakestraw, who is appointed for that service.”

Thereafter, most companies established in America issued a mark; some were of lead, others of cast iron or tin. From 1870 to about 1890, the more modern American offices made use of small metal plates, having the name of the company thereon, in their agency business. These plates were freely scattered throughout the smaller towns and villages more for advertisements, probably, than for any other special purpose, although insured parties were occasionally met with who did not consider themselves safe from fire unless this plate was affixed to their hous...