![]()

PART ONE—The Evolution of Soviet Rule

1 The Pre-1917 Foundations for Soviet Rule

1 A Statement of Basic Considerations

IT IS the present hypothesis that the modern Soviet state is to be understood primarily as the consequence of a peculiarly single-minded effort by an extraordinarily centralized regime to pursue two related but not identical goals: the maintenance of its own absolute internal power over Russian society, and the maximization over time of its power vis-à-vis the external world. These twin objectives have interacted on each other. Moreover, they have to some extent supported each other, but not on all occasions; when conflict has arisen between them, the first has had priority thus far in the history of the Soviet regime.

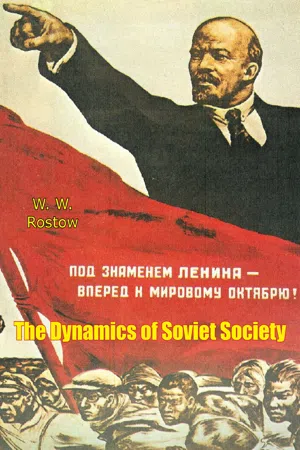

These interlocking characteristics of the regime emerged step by step out of a historical process rather than from a conscious plan. The origins of the process can be traced back to certain elements in the history and thought and personality of the chief revolutionary leaders, notably Lenin, and reflected in the political party he organized. These men were predisposed to make certain policy choices when confronted with the alternatives open to them before, during, and after the Russian Revolution of 1917. They did not consciously plan the Soviet regime which emerged. Their predispositions, when confronted by events and forces outside their control, led to a series of short-run decisions which, over time, shaped the course of the Soviet regime. In particular, this accumulation of decisions led systematically: (1) toward the evolution of a system of centralized and absolute political power dominated by one man; (2) toward a bureaucratized, hierarchical structure of institutions and a related system of income distribution designed to maximize efficiency; (3) toward a systematic statist and nationalist alternation in Marxist ideology, and, within the framework of the modified ideology, toward a conservative, traditionalist pattern for social, intellectual, and cultural life; (4) toward that organization of the Russian economy which would maximize the rate of industrial growth and military strength, leaving for consumption that minimum compatible with the maintenance of life and efficiency within the working force. The emergence of this pattern for society—a pattern fully formed in the course of the 1930’s—has set in motion forces, not fully within the power of Soviet executive control, which are, in turn, changing the pattern of Soviet life and institutions and which promise to alter that society still further in the future.

Since the value judgments which have been central to the shaping of Soviet life were effectively, if not finally, crystallized in the outlook of Lenin and some of his colleagues, it is important to examine the foundations of their thought, and, especially, to clarify the manner in which they differed from political figures of the Western world in this century.

The Russian revolutionaries who formed the Bolshevik Party evidently did not fully share the value judgments which underlie the political, social, and economic techniques of Western societies. These might be summarized as follows:

1. Individual human beings represent a unique balancing of motivations and aspirations which, despite the conscious and unconscious external means that help shape them, are to be accorded a moral and even religious respect; the underlying aim of society is to permit these individual complexes of motivations and aspirations to have their maximum expression compatible with the well-being of other individuals and the security of society.

2. Governments thus exist to assist individuals to achieve their own fulfillment; to protect individual human beings from the harm they might do one another; and to protect organized societies against the aggression of other societies.

3. Governments can take their shape legitimately only from some effective expression of the combined will and judgments of individuals, on the basis of one man one vote.

4. Some men aspire to power over their fellow-men and derive satisfaction from the exercise of power aside from the purposes to which power is put. The fundamental human quality in itself makes dangerous to the well-being of society the concentration of political power in the hands of individuals and groups even where these groups may constitute a majority. Habeas corpus is the symbol and, perhaps, the foundation of the most substantial restraint—in the form of due process of law—men have created to cope with this danger.

From Plato on, political scientists have recognized that men may not understand their own best interest, and, in particular, that they may be short-sighted and swayed by urgent emotions in their definition of that interest. As between the individuals limitation in defining wisely his own long-run interest and his inability wisely to exercise power over others, without check, democratic societies have broadly chosen to risk the former rather than the latter danger in the organization of society, and to diminish the former danger by popular education, the inculcation of habits of individual responsibility, and by devices of government which temper the less thoughtful political reactions of men. From Plato to Stalin, however, there have been those who have chosen, intellectually or in practice, to risk the latter danger.

From this definition the democratic element within a society emerges as a matter of degree and of aspiration. Aware of the abiding weaknesses of man as a social animal, the democrat leans, nevertheless, to the doctrine of Trust the People rather than Father Knows Best. The pure democratic conception is however, compromised to some extent in all organized societies by the need to protect individuals from each other, by the need to protect the society as a whole from others, and by the checks installed to protect the workings of the society from man’s frequent inability wisely to define his own long-run interest. Even when societies strive for the democratic compromise, the balance between liberty and order which any society can achieve and still operate effectively, and the particular form that balance will take, are certain to vary. They will vary not only from society to society, but also within one society in response to that society’s cultural heritage, the state of education of its citizens, and the nature of the problems it confronts as a community. It is evident that some present societies, like their historical counterparts, have not had and do not now have the capability of combining effective communal action with a high degree of what is here called the democratic element. Both history and the contemporary scene offer instances of governments in which the balance of power is heavily in the hands of the state rather than in the hands of the individual citizens who comprise it.

Within the infinite array of possible balances, a totalitarian regime constitutes an extreme case. It can be defined as a state in which the potentialities for control over society by governmental authority are exploited to the limit of available modern techniques—where no significant effort is made to achieve the compromise between the sanctity of the individual and the exigencies of efficient communal life; where the moral weakness of men in the administration of concentrated power is ignored; where the aspiration toward a higher degree of democratic quality is not recognized as a good; and where, conversely, the extreme authority of concentrated power is projected as an intrinsic virtue.

Whether the democratic value judgments are regarded as good or bad, it is basic to an understanding of the Soviet system that they were only partially shared by Marx, and by Lenin and those others who made the Soviet Revolution and who, step by step and perhaps partially against their own expectations, formed thereafter a totalitarian regime in Russia. This transition is believed to have its roots in certain elements within Marxist thought; in the conspiratorial Russian revolutionary tradition which focused obsessively on the destruction of tsarist autocracy; in the problems and experience of prerevolutionary conspiracy; and in the human qualities of the revolutionary leaders. Its final extreme character has been permitted by the exploitation of control potentialities inherent in the techniques of modern society.

2 Some Observations on Marx and Lenin

In view of the extraordinary energy and attention subsequently given by the Soviet state to the mechanics of handling power, it is ironic that Marx’s political ideas were so incompletely developed and profoundly confused. They consisted of an ill-digested amalgam of three major elements which in practice have led to conflicting courses of action. The three elements are these:

1. The notion of a scientifically predetermined course for history in which political power and leadership belonged legitimately only to those who understood the scientific key, i.e., the true Marxists.

2. The notion that the achievement of certain democratic values, in the humanistic eighteenth-and nineteenth-century sense, would automatically accompany the transition from capitalism to socialism.

3. The notion that all societies would pass, by means of class struggles, from feudal to bourgeois-capitalist to socialist stages, in each stage of which political power would be exercised on behalf of a dominating class; and that the process would end with the mystically enunciated withering away of the state upon the emergence of a classless society.

Soviet Russia has seen the gradual triumph of the first of these elements and the virtual, but not complete, elimination of the other two. As discussed below, the resolution of the human dilemma set up by a deterministic conception of history resulted in an identification of historical correctness with the ability to seize, hold, and expand power.

The first of these three elements in Marx was early harnessed, in the Bolshevik movement, to the eternal human craving for power and to familiar techniques for seizing and holding power. This mélange of quasi-philosophical rationale with ancient human motivations and methods dominated the careers of both Lenin and Stalin. Bolshevism only slowly divested itself (and then incompletely) of the second of these elements; that is, a heritage of humanistic democratic values. The third element which, if pursued, would have forced the Bolsheviks to conduct a revolution in 1917 on behalf of bourgeois capitalism was clearly jettisoned by Lenin before his return to Petersburg from Switzerland in April 1917. The mutilation of Marxism caused by the “premature” achievement of the “dictatorship of the proletariat” has been more or less successfully concealed in subsequent Soviet elaborations of Marxism, which have managed to rationalize the current existence of a powerful state while continuing to hold up the ultimate objective of its disappearance. To this rationale, an identification of the interests of the Russian Communist state with the ultimate goals of Communist ideology has been central.

Marx’s doctrines were formulated at a time in the nineteenth century when men were excited by apparent analogies between the course of societies and the process of change in the natural world, as elaborated by a sequence of scientists who defined evolution in terms of certain fixed laws of adaptation. These laws, in Marx, assumed the form of a hypothesis which made the social, political, and cultural texture of societies dependent on material and economic forces.

Applied to societies, the evolutionary hypotheses resulted in theories of historical change. Men differed, of course, in their interpretation of the pattern history had followed and was likely to follow. The analogy with the evolution of the physical world had the following important effect: it appeared to define a future which would be correct in terms of natural laws and apparently independent of the individual judgments of men or of the short-run processes of politics.

It is the notion of a scientifically objective and, therefore, “correct” course for history which, in part, led to the frame of mind of the Marxist revolutionaries. They believed that Marx had formulated the theory which would determine and therefore permit prediction of the course of history; and they were led thereby to the view that those political actions were correct which moved societies along this historically predetermined path. The Marxists never accepted, or they abandoned, the lessons of some two thousand years of Western thought which regarded the handling of state power in relation to the individual as a distinct problem in all forms of society. Marxism, in one of its aspects, simply assumed away the problem. It held that the state was solely the instrument for class oppression by the historically dominant class and that the correctness of political action lay not in its substance or method of application but in its relation to the effective exercise of class power at different historical stages. It was on these quasi-scientific foundations that Lenin built his conception of the Party as the disciplined instrument of Marxist history, responsible only to its own correct analysis and for the application of correct laws of historical change.

The Party—the True Marxists—became a type of Hegelian hero. The acceptance of the notion of a correct and predeterminable path for history gave special status in the process of politics to those who understood that path. The Party appeared to receive sanction, by the acceptance of this doctrine, to take whatever steps might appear to them necessary, in the light of their Marxist analysis, to move the political process in the predetermined direction. The acceptance of this element in the Marxist dogma relieved the Soviet revolutionaries from the responsibility of considering systematically the manner in which the individual aspirations of men related to the political process, or the manner in which the political process must be shielded from the frailties of human ambition and ignorance in the handling of power.

In its own eyes the Bolshevik Party thus had the right and duty to force the correct path for history. Since a group finds it difficult to agree on what is correct at any given complex moment in history, the exigencies of political practice converted this doctrine into a system in which correctness was defined by that man who succeeded in surviving and dominating the political situation; and his consequent decisions were executed by the disciplined faithful.

This whole pattern of thought has been explicit in the Communist tradition since at least 1902 when Lenin published his famous What Is To Be Done? Lenin there combats the notions of his opponents within the revolutionary movement who wished to see a deterministic Marxism harnessed to some form of democratic or popular political process. He uses two main lines of argument:

1. Without the leadership of the proletariat by professional Marxist revolutionaries, the working class might seek, not revolution but ameliorative advances under a trades’ union banner; and

2. Only a dictatorship of the proletariat, as opposed to the parliamentary play of political forces, would move history along the correct path.

On the basis of these fundamental judgments he called for a tightly disciplined organization of the revolutionary party.

There was another and more practical basis for Lenin’s belief that a disciplined dictatorial group must dominate political action if such action was to be “correct.” He and his colleagues were engaged in revolutionary agitation. They worked largely underground in Russia or from exile by illegal means. They faced real dangers and the practical problem of subversive action. Lenin’s elder brother, Alexander, had been hanged as the result of an abortive students’ conspiracy. Lenin’s justification for a tightly disciplined, centrally directed political party was thus made not only in terms of one strand in Marxist political theory, but also in terms of efficient revolutionary practice. There was logic in the marriage of Marxism (with its ambiguities about the political process, but its special sanctions for the true Marxists) with the urgent tasks of energetic revolutionaries. This logic led to a conception of the handling of political power by a central small unit, operating without any formal check on the legitimacy or correctness of its judgments except that provided by discussion within the kind of politically irresponsible group which tends to fall under the domination of a single leader. Lenin fully accepted Engels dictum: “Conspiratorial methods...require a dictatorship if they are to be successful.”

The tactical aspects of Lenin’s doctrine, with its emphasis on the need for f...