- 275 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

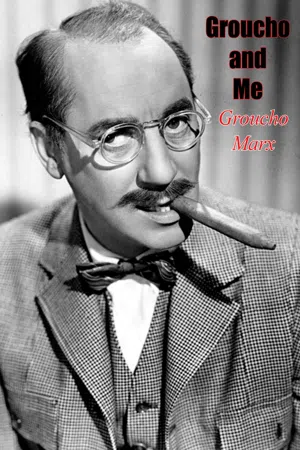

Groucho and Me

About this book

The "Me" in the title is a comparatively unknown Marx named Julius (1895-1977), who, under the nom de plume of Groucho, enjoyed a sensational career on Broadway and in Hollywood with such comedy classics as Animal Crackers, Monkey Business, Horse Feathers, Duck Soup, A Night at the Opera, and A Day at the Races. His solo career included work as a film actor, television game show emcee, and author of The Groucho Letters, Memoirs of a Mangy Lover, and his classic autobiography, Groucho and Me.

With impeccable timing, outrageous humor, irreverent wit, and a superb sense of the ridiculous, Groucho tells the saga of the Marx Brothers: the poverty of their childhood in New York's Upper East Side; the crooked world of small-time vaudeville (where they learned to carry blackjacks); how a pretzel magnate and the graceless dancer of his dreams led to the Marx Brothers' first Broadway hit, I'll Say She Is!, how the stock market crash in 1929 proved a godsend for Groucho (even though he lost nearly a quarter of a million dollars); the adventures of the Marx Brothers in Hollywood, the making of their hilarious films, and Groucho's triumphant television series, You Bet Your Life!. Here is the life and lunatic times of the great eccentric genius, Groucho, a.k.a. Julius Henry Marx.

"The book is never less than readable and its glimpses of American show business at its least glamorous are simple, true and sometimes rather touching."—Times Literary Supplement

"My advice is to ration yourself to a chapter a night—it's that delectable."—Chicago Sunday Tribune

With impeccable timing, outrageous humor, irreverent wit, and a superb sense of the ridiculous, Groucho tells the saga of the Marx Brothers: the poverty of their childhood in New York's Upper East Side; the crooked world of small-time vaudeville (where they learned to carry blackjacks); how a pretzel magnate and the graceless dancer of his dreams led to the Marx Brothers' first Broadway hit, I'll Say She Is!, how the stock market crash in 1929 proved a godsend for Groucho (even though he lost nearly a quarter of a million dollars); the adventures of the Marx Brothers in Hollywood, the making of their hilarious films, and Groucho's triumphant television series, You Bet Your Life!. Here is the life and lunatic times of the great eccentric genius, Groucho, a.k.a. Julius Henry Marx.

"The book is never less than readable and its glimpses of American show business at its least glamorous are simple, true and sometimes rather touching."—Times Literary Supplement

"My advice is to ration yourself to a chapter a night—it's that delectable."—Chicago Sunday Tribune

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Groucho and Me by Groucho Marx in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Media & Performing Arts & Film & Video. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Subtopic

Film & VideoGROUCHO AND ME

CHAPTER 1 — WHY WRITE WHEN YOU CAN TELEGRAPH YOUR PUNCHES?

The trouble with writing a book about yourself is that you can’t fool around. If you write about someone eke, you can stretch the truth from here to Finland. If you write about yourself, the slightest deviation makes you realize instantly that there may be honor among thieves, but you are just a dirty liar.

Although it is generally known, I think it’s about time to announce that I was born at a very early age. Before I had time to regret it, I was four and a half years old. Now that we are on the subject of age, let’s skip it. It isn’t important how old I am. What is important, however, is whether enough people will buy this book to justify my spending the remnants of my rapidly waning vitality in writing it.

Age is not a particularly interesting subject. Anyone can get old. All you have to do is live long enough. It always amuses me when the newspapers run a picture of a man who has finally lived to be a hundred. He’s usually a pretty beat-up individual who invariably looks closer to two hundred than the century mark. It isn’t enough that the paper runs a photo of this rickety, hollow shell. The ancient oracle then has to sound off on the secret of his longevity. “I’ve lived longer than all my friends,” he croaks, “because I never used a mattress, always slept on the floor, had raw turkey liver every morning for breakfast, and drank thirty-two glasses of water a day.”

Big deal! Thirty-two glasses of water a day. This is the kind of man who is responsible for the water shortage in America. Fortunes have been spent in the arid West, trying to convert sea water into something that can be swallowed with safety, and this old geezer, instead of drinking eight glasses of water a day like the rest of us, has to guzzle thirty-two a day, or enough water to keep four normal people going indefinitely.

I still can’t understand why I let the publishers talk me into tackling this job. Just walk into any bookstore and take a look at the mountain of books that are currently published and expected to be sold. Most of them are written by professionals who write well and have something to say. Nevertheless, a year from now most of these books will be on sale at half price. If by some miracle this one should become a best seller, the tax department would get most of the money. However, I don’t think there’s much danger of this. Why should anyone buy the thoughts and opinions of Groucho Marx? I have no views that are worth a damn, and no knowledge that could possibly help anyone.

The big sellers are cookbooks, theological tomes, “how to” books, and rehashings of the Civil War. Their motto is, Keep a Civil War in Your Head.” Titles like, How to Be Happy Though Miserable, Cook Your Way into Your Husbands Heart and Why General Lee Blew the Duke at Gettysburg sell millions of copies. How can I ever compete with them?

I don’t know anything about cooking. On those frequent occasions when my current cook storms out, shouting, “You know what you can do with your kitchen!” only the fact that I have a fairly good supply of pemmican left over from my last trip to Winnipeg saves me from starvation. Oh, I have some men friends who can wrap a barbecue apron adorned with funny sayings around their waists, and in two shakes of a lamb’s tail (or forty minutes on the clock) whip up a meal that would make Savarin turn in his bouillabaisse, but cooking is just not my cup of tea. If I had attempted to write a cookbook it would have sold about three copies.

I did toy with the idea of doing a cookbook, though. The recipes were to be the routine ones: how to make dry toast, instant coffee, hearts of lettuce and brownies. But as an added attraction, at no extra charge, my idea was to put a fried egg on the cover. I think a lot of people who hate literature but love fried eggs would buy it if the price was right. Offhand, this seems like a crazy idea, but a lot of things that seemed nutty at first have turned out to be substantial contributions to mankind’s comfort.

Take mouse traps, for example. Mice weren’t always caught with traps. Only a few centuries ago, if a man wanted to catch a mouse (and many men did), he had to sneak up to a hole in the corner of the kitchen with a piece of cheese clamped between his teeth. Incidentally, this is where the expression, “Keep your trap shut” (usually uttered by the wife just before retiring) came from.

There are many things sold on TV today that are fairly meretricious. People buy these products because they are merchandised with dogged persistence and more than a soupçon of deceit. This, of course, doesn’t apply to any of the legitimate sponsors, but mainly to the local charlatans who stop at nothing.

Perhaps to merchandise this book wisely I ought to give away not only the previously mentioned fried egg, but as an added attraction (at no extra charge) I should give away with each and every book, a hundred pounds of seed com. Not ninety pounds, mark you, not eighty pounds, but one hundred pounds. Where am I going to get the com? I have already anticipated your question. I’m going to get it from the farmer. For years the American public has been getting it in the neck from the farmer and, in return, all we have received is a large bill for farm relief and rigid price supports.

The reason the farmer gets away with so much is that when a city dweller thinks of the farmer he visualizes a tall, stringy yokel, with hayseed in his few teeth, subsisting on turnip greens, skimmed milk and hog jowls and living in a ramshackle dump with his mule fifty miles from nowhere. But what’s the good of my trying to describe it? Erskine Caldwell wrapped it up neatly in God’s Little Acre.

This kind of farmer may have existed years ago, but today the farmer is the best-protected citizen in the entire economy. As a city dweller, I can assure you that there is no love lost between the urbanite and the farmer (unless the farmer has a daughter).

Each year the government is faced with the same problem—how to dispose of the corn surplus. They’ve tried everything: storing it on battleships, dumping it in silos (with the hope that the rats and squirrels will make away with some of it); they’ve even tried giving it away free to the moonshiners. But the White Mule business ain’t what it used to be. The moonshiners now want potatoes because the American public has switched over to vodka. Well, the government’s problem can be solved very easily. Just give me the corn my book so sorely needs.

The government’s eternal solicitude for the rustic has got the rest of the country gagging. Why don’t they do something for the book publisher and the author? Why don’t they do away with literary critics who, in three fine sentences, can cripple the sale of any book? Did you ever hear of a farm critic coming out and saying, “Farmer Snodgrass’ corn is not up to his last year’s crop.” Or, “Another year’s crop like this one, and he’ll be back digging sewers for the county asylum.”

The book publishers of America, you’ll notice, have no lobby in Washington looking after their interests. They have a surplus of books they would like to plow under, but they haven’t got enough money to buy the hole to bury them in.

The public is pretty angry at the farmer. No matter how many farmers we plow under, those fake rustics manage to gouge more money out of the government than all the other pressure groups combined. Now it’s about time the American farmers did something for the people. So, if the publishers who sucked me into this job have anything on the ball, instead of hanging around Madison Avenue lapping up vodka martinis, they should be out hustling, putting pressure on the government and also on the farmers. If my publishers are successful in getting the free seed com, this could easily become The Book of the Year. Just think what you would get for your lousy four bucks—a fried egg, a bag of com, and the combined wisdom of Groucho Marx. And all for a poultry four dollars. And remember, this book wouldn’t have to be sold just in the bookstores. It could be sold in supermarkets, lunchrooms, garden supply shops and drive-in theatres.

Nowadays things have to be merchandised. You can’t just write a book and expect the public to rash out and buy it unless it’s a classic. I could write a classic if I wanted to, but I’d rather write for the little people. When I walk down the street I don’t care a hoot if people point a finger at me and say, “Look at him. He just wrote a classic!” No, I’d rather have them say admiringly, “What a trashy writer! But who else writing today gives away a fried egg and a bag of corn with each copy of his book?”

They say that every man has a book in him. This is about as accurate as most generalizations. Take, for example, “Early to bed, early to rise, makes a man you-know-what.” This is a lot of hoopla. Most wealthy people I know like to sleep late, and will fire the help if they are disturbed before three in the afternoon. Pray tell (I cribbed that from Little Women), who are the people who get up at the crack of dawn? Policemen, firemen, garbage collectors, bus drivers, department store clerks and others in the lower income bracket. You don’t see Marilyn Monroe getting up at six in the morning. The truth is, I don’t see Marilyn getting up at any hour, more’s the pity. I’m sure if you had your choice, you would rather watch Miss Monroe rise at three in the afternoon than watch the most efficient garbage collector in your town hop out of bed at six.

Unfortunately, the temptation to write about yourself is irresistible, especially when you are prodded into it by a crafty publisher who has slyly baited you into doing it with a miserly advance of fifty dollars and a box of cheap cigars.

It all started innocently enough. Years ago, influenced by the famous diaries of Samuel Pepys, I too started keeping a diary. Incidentally, I think that the Peeps or Peppies or Pipes diaries would be much more popular today had there been a universal pronunciation of his name. Many times, at a fashionable literary dinner party, I have been tempted to discuss the Pepys diaries, but I was always uncertain as to the proper pronunciation of his name. For example, if you said “Peeps” the lady on your left would invariably say, “Pardon me, but don’t you mean Pipes?” And the partner on your right would say, “I’m sorry, but you’re both wrong. It’s Peppies.” If Peeps, Pipes or Peppies had been smart enough to pick a name like Joe Blow, every schoolboy in America would be reading his diaries today instead of being out in the streets stealing hub caps.

At this point during the party, if you are wise, you abandon the literary gambit and Pepys and plunge into some subject that you know something about, such as the batting and fielding averages of George Sisler. A discussion of George Sisler will quickly bring about the exodus of the two dumpy dowagers between whom your hostess has so thoughtfully planted you. This gives you an opportunity to smile tenderly at that cute little starlet across the table, the one whom nature has so generously endowed with the good things in life.

I don’t know what TV and free love have done to the book publishing business, but one of the biggest blocks to the launching of a literary masterpiece (which this unquestionably will be) is the freeloader.

Getting off the subject of Marilyn Monroe—and don’t think it’s easy—I’d like to say a few unkind words about the miserly Scrooge known in bookish circles as “the browser.” I’m sure you have seen him in many a bookstore. He reads a review in The New Yorker, Atlantic Monthly or The Saturday Review of some new book that sounds pretty tasty. Fortified with this briefing, he casually enters a bookstore, ferrets out a copy of the book, and if he is a rapid reader (or “skimmer,” as he is known in the trade) he gets through it pretty thoroughly in forty-five minutes. He then scrams unobtrusively through a side door so that he can come back another day and help pauperize some other hard-working author.

In the event that the owner of the bookstore is foolish enough to ask if he can be of assistance, this creep (knowing he is trapped) will be crafty enough to ask for Frangani’s History of the Chinese Wall or A Comprehensive Compendium of the Argine Confederacy. A man will think nothing of paying four or five dollars for a pair of pants, but he’ll think a long time before he’ll pony up the same amount of money for a book.

This opus started out as an autobiography, but before I was aware of it I realized it would be nothing of the kind. It is almost impossible to write a truthful autobiography. Maybe Proust, Gide and a few others did it, but most autobiographies take good care to conceal the author from the public. In nearly all cases, what the public finally buys is a discreet tome with the facts slyly concealed, full of hogwash and ambiguity.

Except in the case of professional writers, most of these untrue confessions are not even written by the man whose name is on the book jacket. Large letters will proclaim it to be THE AUTOBIOGRAPHY OF CHARLES W. MOONSTRUCK, and letters small enough to fit the head of a pin will whisper, “As told to Joe Flamingo.” Joe Flamingo, the actual writer, is the drudge who has wasted two years of his life for a miserly stipend, setting down and embellishing the few halting words of Charles W. Moonstruck. When the book finally appears in print, Moonstruck struts all over town asking his friends (the few he has), “Did you read my book?...You know, I’ve never written before....I had no idea writing was so easy!...I must do another book soon.”

He forgets that he hasn’t written a word of this undistinguished epic and, except for the fact that he told his “ghost” where he was born and when (he even lied a little about this), his literary stooge had to ad lib and create the three hundred deathless pages himself.

This is indeed the age of the “ghost.” Most of the palaver that emanates from bankers, politicians, actors, industrialists and others in the high-bracket zones is written by undernourished hacks who keep body and soul together writing reams of schweinerei for flannel-mouthed stuffed shirts. Like it or not, this is the kind of an age we’re living in.

I’m really sticking my neck out with this blast at ghost-writing. I know damned well I’m no Faulkner, Hemingway, Camus or Perelman...or even Kathleen Winsor. As a matter of fact, I’m not even the same sex as Kathleen. But every word of this stringy, ill-written farrago is being sweated out by me.

The fact remains that most autobiographies don’t have too many facts remaining. Ninety per cent of them are ninety per cent fiction. If the real truth were ever written about most men in public life, there wouldn’t be enough jails to house them. Lying has become one of the biggest industries in America.

Let’s take, for example, the relationship that exists between husband and wife. Even when they’re celebrating their golden wedding anniversary and have said “I love you” a million times to each other, publicly and privately, you know as well as I do that they’ve never really told each other the truth—the real truth. I don’t mean the superficial things like, “Your mother is a louse!” or “Why don’t we get an expensive car instead of that tin can were riding around in?” No, I mean the secret thoughts that run through their minds when they wake up in the middle of ...

Table of contents

- Title page

- TABLE OF CONTENTS

- DEDICATION

- CHAPTER 1 - WHY WRITE WHEN YOU CAN TELEGRAPH YOUR PUNCHES?

- CHAPTER 2 - WHO NEEDS MONEY? (WE DID)

- CHAPTER 3 - HOME IS WHERE YOU HANG YOUR HEAD

- CHAPTER 4 - OUT ON A LIMB OF MY FAMILY TREE

- CHAPTER 5 - MY YOUTH-AND YOU CAN HAVE IT

- CHAPTER 6 - HAVE NOTHING, WILL TRAVEL

- CHAPTER 7 - THE FIRST ACT IS THE HARDEST

- CHAPTER 8 - A WAND’RING MINSTREL, I

- CHAPTER 9 - A SLIGHT CASE OF AUTO-EROTICISM

- CHAPTER 10 - TANK TOWNS, PTOMAINE AND TOMFOOLERY

- CHAPTER 11 - A HOMEY ESSAY ON HOUSEMANSHIP

- CHAPTER 12 - SOME CLOWNING THAT WASN’T IN THE ACT

- CHAPTER 13 - OUT OF OUR LITTLE MINDS AND INTO THE BIG TIME

- CHAPTER 14 - RICH IS BETTER

- CHAPTER 15 - HOW I STARRED IN THE FOLLIES OF 1929

- CHAPTER 16 - WHITE NIGHTS, WHY ARE YOU BLUE?

- CHAPTER 17 - MEANWHILE, BACK AT THE RANCH HOUSE

- CHAPTER 18 - THEY CALL IT THE GOLDEN STATE

- CHAPTER 19 - INSIDE HOLLYWOOD

- CHAPTER 20 - THE PATIENT’S DILEMMA

- CHAPTER 21 - WHY DO THEY CALL IT LOVE WHEN THEY MEAN SEX?

- CHAPTER 22 - MELINDA AND ME

- CHAPTER 23 - MY PERSONAL DECATHLON

- CHAPTER 24 - YO HEAVE HO, AND OVER THE RAIL

- CHAPTER 25 - GO FISH

- CHAPTER 26 - FOOT IN MOUTH DISEASE

- CHAPTER 27 - WHAT PRICE PUMPERNICKEL?

- CHAPTER 28 - YOU BET MY LIFE

- REQUEST FROM THE PUBLISHER