- 155 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

The Glorious First of June

About this book

First published in 1961, this is a fascinating account of the battle between the fleets of the England's Lord Howe and France's Admiral Villaret-Joyeuse during the French Revolutionary Wars.

Known as the Glorious First of June (also known in France as the Bataille du 13 prairial an 2 or Combat de Prairial), the action on 1 June 1794 was the culmination of a campaign that had criss-crossed the Bay of Biscay over the previous month in which both sides had captured numerous merchant ships and minor warships and had engaged in two partial, but inconclusive, fleet actions. The British Channel Fleet under Admiral Lord Howe attempted to prevent the passage of a vital French grain convoy from the United States, which was protected by the French Atlantic Fleet, commanded by Rear-Admiral Villaret-Joyeuse. The two forces clashed in the Atlantic Ocean, some 400 nautical miles (700 km) west of the French island of Ushant on 1 June 1794.

Known as the Glorious First of June (also known in France as the Bataille du 13 prairial an 2 or Combat de Prairial), the action on 1 June 1794 was the culmination of a campaign that had criss-crossed the Bay of Biscay over the previous month in which both sides had captured numerous merchant ships and minor warships and had engaged in two partial, but inconclusive, fleet actions. The British Channel Fleet under Admiral Lord Howe attempted to prevent the passage of a vital French grain convoy from the United States, which was protected by the French Atlantic Fleet, commanded by Rear-Admiral Villaret-Joyeuse. The two forces clashed in the Atlantic Ocean, some 400 nautical miles (700 km) west of the French island of Ushant on 1 June 1794.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

1 — Lord Howe

THE GLORIOUS FIRST OF JUNE, actually the climax of a series of encounters, was fought in 1794—on a Sunday—between the fleets of Lord Howe and Admiral Villaret-Joyeuse. It took place in the North Atlantic, four hundred and twenty-nine miles west of Ushant, farther out to sea than any other major action in home waters of the days of sail. It was the first tactical victory of the British in the war with Revolutionary and Napoleonic France which lasted for over twenty years (1793-1815). Strategically, it was not a success for Howe, since the French did what they most wanted to do, which was to ensure the safe passage of a convoy of grain from America to their needy country. That particular outcome was not realised in England, at any rate by the public at large, and the sight of six prizes at anchor at Spithead was a tonic to a nation which had begun the war uncertainly, and whose leaders saw no immediate prospect of any important success by land. Its moral effect on the British fleet was lastingly good.

In his day, Lord Howe was known as taciturn—as unshakeable as a rock, and as silent, Horace Walpole once said of him. As if to emphasise the characteristic, little has been written about him since his death, and some of that little is controversial. He left no readily accessible mass of papers and documents, and such letters as have been published are often as involved and stiff in expression as they are beautiful in their hand-writing. Moreover an important phrase which Nelson let fall about a “Lord Howe victory”—meaning one which was not exploited to the limit—has been remembered at Howe’s expense.

While it is true that Howe represented the old navy and Nelson the new, that Howe relied upon tried methods and Nelson explored fresh ones, any idea that Nelson had anything but reverence for Howe can be dismissed at once, with proof to the contrary. When he held office as First Lord of the Admiralty, Howe gave Nelson his one and only peace-time command, the frigate Boreas, and Nelson was grateful. Later, Nelson achieved his own earlier successes as a flag officer under Lord St. Vincent, than whom Howe had no warmer admirer. (“Lord Howe wore blue breeches,” St. Vincent was fond of saying, “and I love to follow his example even in my dress.”) Finally, when news of the victory of the Nile reached London, Howe, who had long been at the head of his profession, and who later became the only man to have received the Order of the Garter for services purely naval in character, wrote at once to Nelson to add his congratulations to the shower he was then receiving.

Lord Howe’s letter was addressed from Grafton Street on 3rd October 1798. It reached Nelson over three months later, when he was in Sicily, depressed that the Neapolitan land campaign he had advocated was in ruins, and overwhelmed with administrative work. Sweeping everything else on one side, he wrote:

“It is only this moment that I had the invaluable approbation of the great, the immortal Earl Howe—an honour the most flattering a Sea-officer could receive, as it comes from the first and greatest Sea-officer the world has ever produced.…”

This was not entirely the language of hyperbole, and Nelson followed up his salute by describing the action he had won at Aboukir Bay in a few sentences of such clarity that they will always remain the best summary of the events of that fiery August night. He did so, he said, because it was to Howe that the Navy owed the efficiency of the system of signals then in use. He added:

“I have never before, my Lord, detailed the Action to any one; but I should have thought it wrong to have kept it from one who is our great Master in Naval tactics and bravery.…”

The letter reached Howe during the last year of his life, and it must have gratified him as coming from one who, though so many years his junior—Howe was commanding a ship of the line when Nelson was a baby—was obviously to succeed to the highest honours in their joint profession.

There is further detail to note about this incident, so creditable to both men. Sir Edward Berry, who had been Nelson’s flag-captain at the Nile and was sent home with dispatches, met Lord Howe shortly after he had written his letter, and was able to tell Nelson that one of the things about the action which had most struck Howe was that “every Captain distinguished himself”. This, said Howe, made the action “singular”. In his own wide experience, he had not met with such a “band of brothers” as Nelson had managed to collect and train.

Time passed, and one day, nearly forty years after Howe’s June action, King William IV was dining at the Brighton Pavilion with a group of naval friends. Among them was Sir Edward Codrington. He was an admiral of striking presence who had been captain of the Orion at Trafalgar and had commanded in chief at the Battle of Navarino in 1827, in the war of Greek liberation, the last full-scale fleet action fought wholly under sail. The talk turned upon Lord Howe: everyone agreed what a sad thing it was that no one had written his life. Codrington was specially disappointed that this was so, for he had known Howe well as a young man, and had served in his flagship at the Glorious First of June.

The King promised to do something about it, and shortly afterwards he summoned Sir John Barrow, Second Secretary of the Admiralty, requesting him to undertake the task. Barrow obeyed, though the task was not finished before William’s reign was over. It remains to this day almost the only venture into Howe biography. Its imperfections are various, not all of them the fault of the author, and it was not, indeed, the shortcomings of Barrow which moved Sir Edward to put pen to paper so much as the impertinence of a reviewer. A gentleman writing in The Spectator in January 1838 actually attributed “shyness and want of nerve” to Lord Howe in his later years, when noticing Barrow’s book. This was too much. All who knew him, Horace Walpole—who did not like him—included, were never in doubt as to Howe’s “constitutional intrepidity”. Codrington, in angry justification of his revered master, made a series of notes about the man who had shown him the qualities of an admiral, and these he inter-leaved into his own copy of Barrow. Many years later Codrington’s daughter, Lady Bourchier, included these notes, and many others, in a massive two-volume memoir of her father. Thanks to her daughterly affection, posterity has been enabled to follow the events of the sea campaign of June 1794 through the eyes of the young officer who was at the finest vantage point—the deck of Howe’s Queen Charlotte—throughout the action.

William IV had suggested to Barrow that certain events in Howe’s life would “require caution in touching upon”. He did not, apparently, specify them in detail, but there is not much doubt that among them was Howe’s failure to exploit his own victory. The idea that he had not done so was immediate, widespread in the fleet though not in the country at large, and justified. What blame can fairly be attached to him must be a matter for the reader’s judgment, when he has considered the facts, and when he recalls Howe’s age at the time of the battle. He was sixty-nine. He had himself once declared that no man over sixty should seek active responsibility at sea. If, as in his case, this was assumed at the personal request of a Sovereign to whom he was devoted, that was quite another thing. In such a matter, it would have been disloyal to refuse the burden.

Howe was, in fact, the oldest sea-officer to have won a naval victory on the scale of the First of June. His nearest rival was Adam Duncan, who beat the Dutch at Camperdown three years later, at the age of sixty-six. Rodney was sixty-four when he won the Battle of the Saints in 1782, and in the opinion of his brilliant second, Samuel Hood, failed as badly as Howe in following it up. Sir John Jervis, later the Earl of St. Vincent, was a year younger than Rodney when he beat the Spaniards, and of a toughness which preserved him till the age of eighty-eight. The future was with the younger men. Nelson was not quite forty when he defeated Brueys at the Nile, and Wellington much the same age when he began his unparalleled services in the Peninsula. A generous verdict would be that Howe’s example was transformed by his young successors, but that none have exceeded him in the range of professional accomplishments, and in single-minded protracted devotion to the maritime affairs of his country.

“We can never really picture Nelson’s fleet until we have understood Lord Howe’s”, wrote Archbishop David Mathew in The Naval Heritage. To understand Lord Howe is to appreciate not only the tradition upon which his successors built, but how much they improved upon it, a result due in equal parts to genius and to experience of prolonged warfare.

II

The French Republic declared war on Great Britain in February 1793, over a year before the battle. A state of belligerence could not long have been delayed, once the enemy had seized the Scheldt from Dutch control in violation of treaty obligations, and thus threatened British trade. For with a hostile sea-power based on Antwerp, North Sea traffic was in danger, and an important gateway to the Continent was barred.

Britain had been filled with horror at the execution of Louis XVI earlier in the year, and the decree of the French Convention offering “assistance to all people who wish to recover their liberty” was an act of provocation designed to create a fifth-column, as the phrase now is, in any country which preserved ancient forms of Government. The Jacobin extremists announced the intention of planting “50,000 Trees of Liberty in England”, and there were some misguided enough to believe that it might be a good thing. Most of them soon learnt (from the bitter experience of other people) that a Tree of Liberty, planted by French hands on alien soil, meant a fight first against rapine and then against extinction.

The Prime Minister, William Pitt, was the son of the great Earl of Chatham, architect of victory in the Seven Years War (1756-1762) and a passionate denouncer of the conduct of the succeeding war of American Independence (1775-1783). It had been Pitt’s hope and ambition, by means of increase of trade and conservative finance, to make his country strong again after her disaster and humiliation in the New World: to be as dynamic and successful in peace as his father had been in war. For a time, it seemed as if he would succeed. That he did not do so was the fault not of his own intention and leadership, but of events over which he could have no influence whatever.

These events had succeeded one another in rapid, almost bewildering succession: the formation of a French National Assembly in place of the ancient pattern of Three Estates, nobles, clergy and citizens; the storming of the Bastille, symbol of the old régime; the foiled attempt of the King to flee the country; declaration of war on Austria; the formal overthrow of the monarchy, finally the death of the King and the spread of a reign of terror, which was partly due to hysteria at the fact that foreign armies were at the frontiers of France.

Owing to a succession of alarms with both Spain and France in the years immediately before the opening of war, Britain was for once reasonably prepared by sea, and she had, moreover, a wealth of officers seasoned in two wars—some of them in three. Better still, she had in Howe and Hood men accustomed to manage large fleets, and it was to these admirals that the direction of affairs at sea was at first given. Hood, an autocratic character on the verge of seventy, but junior to Howe, under whom he had at one time served, was sent to the Mediterranean. Howe, who had always been an Atlantic man, was at the King’s personal direction given chief command of what would now be called the Home Fleet and the Western Approaches. Each complained that the other had been given the pick of the resources: each in fact, was well equipped, by any earlier standard, for the beginning of a naval campaign. It has seldom been Britain’s way to be quite ready for the next war.

Howe’s earlier career is an illustration of what could be looked for in a senior commander, and he could be described as the epitome of the eighteenth century sea-officer. He had the advantage of social rank; he aspired to mastery of every side of naval activity; and he had had the luck to have been in vital areas in time of war. He had invariably emerged with credit, and not seldom with distinction.

On one side, his blood was German. His mother, Maria-Sophia-Charlotte von Kielmansegge, had come over as a child from Hanover with her mother, a favourite of George I. She had married into a landed family which had been prominent in the Revolution of ...

Table of contents

- Title page

- TABLE OF CONTENTS

- DEDICATION

- PREFACE

- ACKNOWLEDGMENT

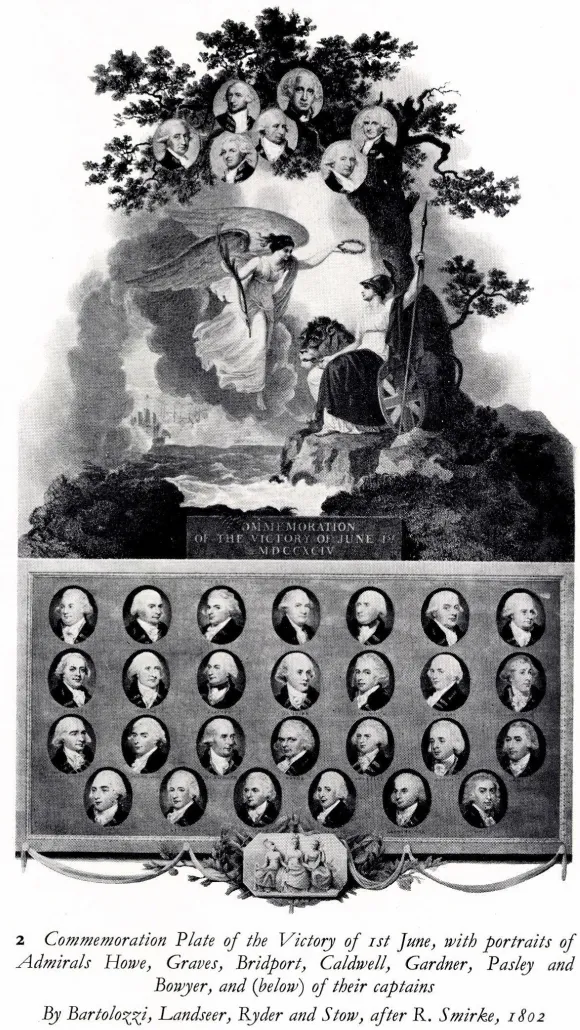

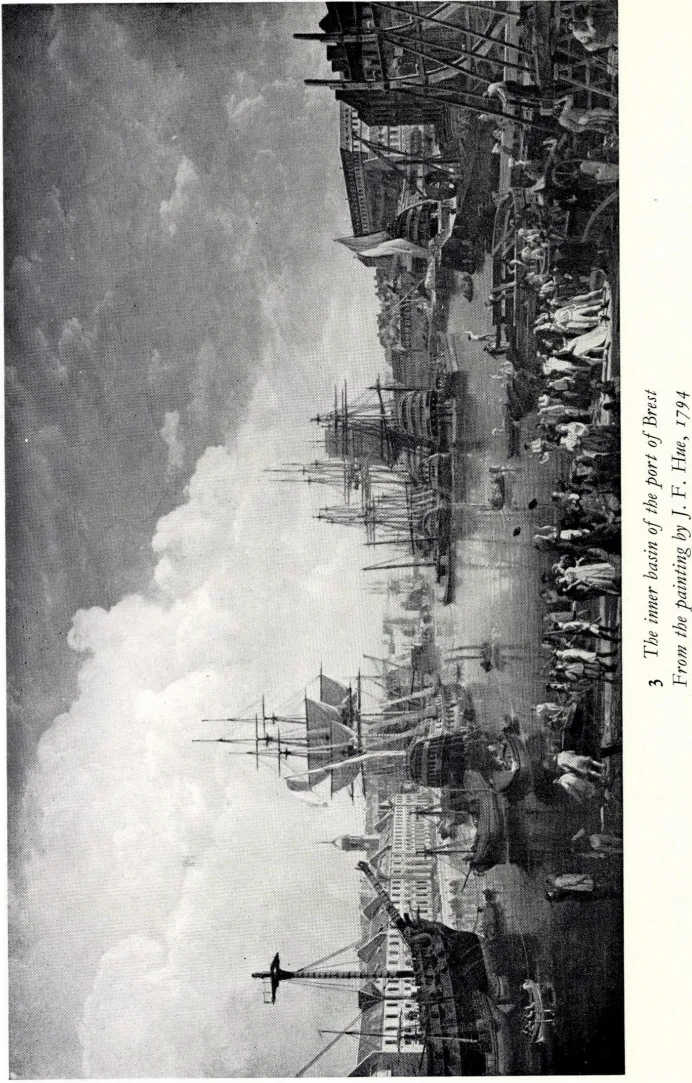

- LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS

- 1 - Lord Howe

- 2 - The “Queen Charlotte”

- 3 - The Enemy

- 4 - Midshipman in the “Defence”

- 5 - The Case of Captain Collingwood

- 6 - Ships in Battle

- 7 - Lady Mary Rejoices

- Epilogue - HONOURS AND AWARDS IN THE NAVY

- APPENDIX I - Lord Howe’s Letters to the Admiralty

- APPENDIX II - Lord Howe’s Fleet

- APPENDIX III - The French Line of Battle on 1st June

- APPENDIX IV - Sources and Acknowledgments

- REQUEST FROM THE PUBLISHER

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access The Glorious First of June by Oliver Warner in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & British History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.