- 123 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

A Tract on Monetary Reform

About this book

In A Tract on Monetary Reform, which was first published in 1923, British economist John Maynard Keynes argues that the objects of British government should be the stability of trade, price, and employment. The gold reserve should be demonetized. However, this does not mean that gold serves absolutely no purpose anymore. Rather, it is a store of value and a means of correcting the influence of a temporarily adverse balance of payment.

"This is a very brilliant as well as a very important book. Like all that Mr. Keynes writers, it is full of matter, and also full of wit…If any argument were wanted to show that whether we like it or not, we must tackle the monetary problem, it is to be found in Mr. Keynes's book. It is a bright light, and though it may, if misused, do harm to the eyesight of some people, it throws a light, and a true light, on the world's dilemma."—The Spectator

"This is a very brilliant as well as a very important book. Like all that Mr. Keynes writers, it is full of matter, and also full of wit…If any argument were wanted to show that whether we like it or not, we must tackle the monetary problem, it is to be found in Mr. Keynes's book. It is a bright light, and though it may, if misused, do harm to the eyesight of some people, it throws a light, and a true light, on the world's dilemma."—The Spectator

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

CHAPTER I—THE CONSEQUENCES TO SOCIETY OF CHANGES IN THE VALUE OF MONEY

MONEY is only important for what it will procure. Thus a change in the monetary unit, which is uniform in its operation and affects all transactions equally, has no consequences. If, by a change in the established standard of value, a man received and owned twice as much money as he did before in payment for all rights and for all efforts, and if he also paid out twice as much money for all acquisitions and for all satisfactions, he would be wholly unaffected.

It follows, therefore, that a change in the value of money, that is to say in the level of prices, is important to Society only in so far as its incidence is unequal. Such changes have produced in the past, and are producing now, the vastest social consequences, because, as we all know, when the value of money changes, it does not change equally for all persons or for all purposes. A man’s receipts and his outgoings are not all modified in one uniform proportion. Thus a change in prices and rewards, as measured in money, generally affects different classes unequally, transfers wealth from one to another, bestows affluence here and embarrassment there, and redistributes Fortune’s favours so as to frustrate design and disappoint expectation.

The fluctuations in the value of money since 1914 have been on a scale so great as to constitute, with all that they involve, one of the most significant events in the economic history of the modern world. The fluctuation of the standard, whether gold, silver, or paper, has not only been of unprecedented violence, but has been visited on a society of which the economic organisation is more dependent than that of any earlier epoch on the assumption that the standard of value would be moderately stable.

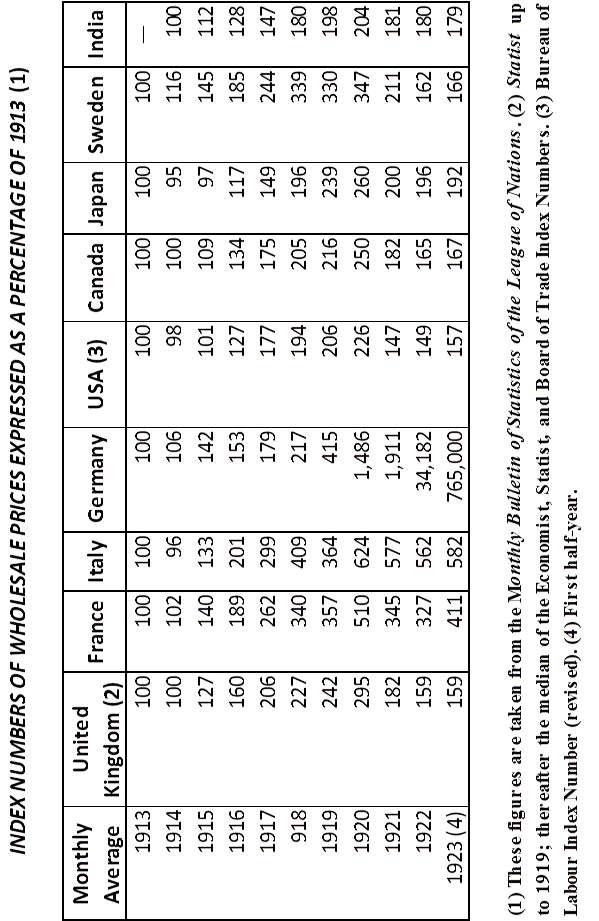

During the Napoleonic Wars and the period immediately succeeding them the extreme fluctuation of English prices within a single year was 22 per cent; and the highest price level reached during the first quarter of the nineteenth century, which we used to reckon the most disturbed period of our currency history, was less than double the lowest and with an interval of thirteen years. Compare with this the extraordinary movements of the past nine years. To recall the reader’s mind to the exact facts, I refer him to the table on the next page.

I have not included those countries—Russia, Poland, and Austria—where the old currency has long been bankrupt. But it will be observed that, even apart from the countries which have suffered revolution or defeat, no quarter of the world has escaped a violent movement. In the United States, where the gold standard has functioned unabated, in Japan, where the war brought with it more profit than liability, in the neutral country of Sweden, the changes in the value of money have been comparable with those in the United Kingdom.

From 1914 to 1920 all these countries experienced an expansion in the supply of money to spend relatively to the supply of things to purchase, that is to say Inflation. Since 1920 those countries which have regained control of their financial situation, not content with bringing the Inflation to an end, have contracted their supply of money and have experienced the fruits of Deflation. Others have followed inflationary courses more riotously than before. In a few, of which Italy is one, an imprudent desire to deflate has been balanced by the intractability of the financial situation, with the happy result of comparatively stable prices.

Each process, Inflation and Deflation alike, has inflicted great injuries. Each has an effect in altering the distribution of wealth between different classes, Inflation in this respect being the worse of the two. Each has also an effect in overstimulating or retarding the production of wealth, though here Deflation is the more injurious. The division of our subject thus indicated is the most convenient, for us to follow,—examining first the effect of changes in the value of money on the distribution of wealth with most of our attention on Inflation, and next their effect on the production of wealth with most of our attention on Deflation. How have the price changes of the past nine years affected the productivity of the community as a whole, and how have they affected the conflicting interests and mutual relations of its component classes? The answer to these questions will serve to establish the gravity of the evils, into the remedy for which it is the object of this book to inquire.

I.—Changes in the Value of Money, As Affecting Distribution

For the purpose of this inquiry a triple classification of Society is convenient—into the Investing Class, the Business Class, and the Earning Class. These classes overlap, and the same individual may earn, deal, and invest; but in the present organisation of society such a division corresponds to a social cleavage and an actual divergence of interest.

1. The Investing Glass.

Of the various purposes which money serves, some essentially depend upon the assumption that its real value is nearly constant over a period of time. The chief of these are those connected, in a wide sense, with contracts for the investment of money. Such contracts—namely, those which provide for the payment of fixed sums of money over a long period of time—are the characteristic of what it is convenient to call the Investment System, as distinct from the property system generally.

Under this phase of capitalism, as developed during the nineteenth century, many arrangements were devised for separating the management of property from its ownership. These arrangements were of three leading types: (1) Those in which the proprietor, while parting with the management of his property, retained his ownership of it—i.e. of the actual land, buildings, and machinery, or of whatever else it consisted in, this mode of tenure being typified by a holding of ordinary shares in a joint-stock company; (2) those in which he parted with the property temporarily, receiving a fixed sum of money annually in the meantime, but regained his property eventually, as typified by a lease; and (3) those in which he parted with his real property permanently, in return either for a perpetual annuity fixed in terms of money, or for a terminable annuity and the repayment of the principal in money at the end of the term, as typified by mortgages, bonds, debentures, and preference shares. This third type represents the full development of Investment.

Contracts to receive fixed sums of money at future dates (made without provision for possible changes in the real value of money at those dates) must have existed as long as money has been lent and borrowed. In the form of leases and mortgages, and also of permanent loans to Governments and to a few private bodies, such as the East India Company, they were already frequent in the eighteenth century. But during the nineteenth century they developed a new and increased importance, and had, by the beginning of the twentieth, divided the propertied classes into two groups—the “business men” and the “investors”—with partly divergent interests. The division was not sharp as between individuals; for business men might be investors also, and investors might hold ordinary shares; but the division was nevertheless real, and not the less important because it was seldom noticed.

By this system the active business class could call to the aid of their enterprises not only their own wealth but the savings of the whole community; and the professional and propertied classes, on the other hand, could find an employment for their resources, which involved them in little trouble, no responsibility, and (it was believed) small risk.

For a hundred years the system worked, throughout Europe, with an extraordinary success and facilitated the growth of wealth on an unprecedented scale. To save and to invest became at once the duty and the delight of a large class. The savings were seldom drawn on, and, accumulating at compound interest, made possible the material triumphs which we now all take for granted. The morals, the politics, the literature, and the religion of the age joined in a grand conspiracy for the promotion of saving. God and Mammon were reconciled. Peace on earth to men of good means. A rich man could, after all, enter into the Kingdom of Heaven—if only he saved. A new harmony sounded from the celestial spheres. “It is curious to observe how, through the wise and beneficent arrangement of Providence, men thus do the greatest service to the public, when they are thinking of nothing but their own gain”{1}; so sang the angels.

The atmosphere thus created well harmonised the demands of expanding business and the needs of an expanding population with the growth of a comfortable non-business class. But amidst the general enjoyment of ease and progress, the extent, to which the system depended on the stability of the money to which the investing classes had committed their fortunes, was generally overlooked; and an unquestioning confidence was apparently felt that this matter would look after itself. Investments spread and multiplied, until, for the middle classes of the world, the gilt-edged bond came to typify all that was most permanent and most secure. So rooted in our day has been the conventional belief in the stability and safety of a money contract that, according to English law, trustees have been encouraged to embark their trust funds exclusively in such transactions, and are indeed forbidden, except in the case of real estate (an exception which is itself a survival of the conditions of an earlier age), to employ them otherwise.{2}

As in other respects, so also in this, the nineteenth century relied on the future permanence of its own happy experiences and disregarded the warning of past misfortunes. It chose to forget that there is no historical warrant for expecting money to be represented even by a constant quantity of a particular metal, far less by a constant purchasing power. Yet Money is simply that which the State declares from time to time to be a good legal discharge of money contracts. In 1914 gold had not been the English standard for a century or the sole standard of any other country for half a century. There is no record of a prolonged war or a great social upheaval which has not been accompanied by a change in the legal tender, but an almost unbroken chronicle in every country which has a history, back to the earliest dawn of economic record, of a progressive deterioration in the real value of the successive legal tenders which have represented money.

Moreover, this progressive deterioration in the value of money through history is not an accident, and has had behind it two great driving forces—the impecuniosity of Governments and the superior political influence of the debtor class.

The power of taxation by currency depreciation is one which has been inherent in the State since Rome discovered it. The creation of legal-tender has been and is a Government’s ultimate reserve; and no State or Government is likely to decree its own bankruptcy or its own downfall, so long as this instrument still lies at hand unused.

Besides this, as we shall see below, the benefits of a depreciating currency are not restricted to the Government. Farmers and debtors and all persons liable to pay fixed money dues share in the advantage. As now in the persons of business men, so also in former ages these classes constituted the active and constructive elements in the economic scheme. Those secular changes, therefore, which in the past have depreciated money, assisted the new men and emancipated them from the dead hand; they benefited new wealth at the expense of old, and armed enterprise against accumulation. The tendency of money to depreciate has been in past times a weighty counterpoise against the cumulative results of compound interest and the inheritance of fortunes. It has been a loosening influence against the rigid distribution of old-won wealth and the separation of ownership from activity. By this means each generation can disinherit in part its predecessors’ heirs; and the project of founding a perpetual fortune must be disappointed in this way, unless the community with conscious deliberation provides against it in some other way, more equitable and more expedient.

At any rate, under the influence of these two forces—the financial necessities of Governments and the political influence of the debtor class—sometimes the one and sometimes the other, the progress of inflation has been continuous, if we consider long periods, ever since money was first devised in the sixth century B.C. Sometimes the standard of value has depreciated of itself; failing this, debasements have done the work.

Nevertheless it is easy at all times, as a result of the way we use money in daily life, to forget all this and to look on money as itself the absolute standard of value; and when, besides, the actual events of a hundred years have not disturbed his illusions, the average man regards what has been normal for three generations as a part of the permanent social fabric.

The course of events during the nineteenth century favoured such ideas. During its first quarter, the very high prices of the Napoleonic Wars were followed by a somewhat rapid improvement in the value of money. For the next seventy years, with some temporary fluctuations, the tendency of prices continued to be downwards, the lowest point being reached in 1896. But while this was the tendency as regards direction, the remarkable feature of this long period was the relative stability of the price level. Approximately the same level of price ruled in or about the years 1826, 1841, 1855, 1862, 1867, 1871, and 1915. Prices were also level in the years 1844, 1881, and 1914. If we call the index number of these latter years 100, we find that, for the period of close on a century from 1826 to the outbreak of war, the maximum fluctuation in either direction was 30 points, the index number never rising above 130 and never falling below 70. No wonder that we came to believe in the stability of money contracts over a long period. The metal gold might not possess all the theoretical advantages of an artificially regulated standard, but it could not be tampered with and had proved reliable in practice.

At the same time, the investor in Consols in the early part of the century had done very well in three different ways. The “security” of his investment had come to be considered as near absolute perfection as was possible. Its capital value had uniformly appreciated, partly for the reason just stated, but chiefly because the steady fall in the rate of interest increased the number of years’ purchase of the annual income which represented the capital.{3} And the annual money income had a purchasing power which on the whole was increasing. If, for example, we consider the seventy years from 1826 to 1896 (and ignore the great improvement immediately after Waterloo), we find that the capital value of Consols rose steadily, with only temporary set-backs, from 79 to 109 (in spite of Goschen’s conversion from a 3 per cent rate to a 2¾ per cent rate in 1889 and a 2½ per cent rate effective in 1903), while the purchasing power of the annual dividends, even after allowing for the reduced rates of interest, had increased 50 percent. But Consols, too, had added the virtue of stability to that of improvement. Except in years of crisis Consols never fell below 90 during the reign of Queen Victoria; and even in ‘48, when thrones were crumbling, the mean price of the year fell but 5 points. Ninety when she ascended the throne, they reached their maximum with her in the year of Diamond Jubilee. What wonder t...

Table of contents

- Title page

- TABLE OF CONTENTS

- ACKNOWLEDGMENT

- PREFACE

- CHAPTER I-THE CONSEQUENCES TO SOCIETY OF CHANGES IN THE VALUE OF MONEY

- CHAPTER II-PUBLIC FINANCE AND CHANGES IN THE VALUE OF MONEY

- CHAPTER III-THE THEORY OF MONEY AND OF THE FOREIGN EXCHANGES

- CHAPTER IV-ALTERNATIVE AIMS IN MONETARY POLICY

- CHAPTER V-POSITIVE SUGGESTIONS FOR THE FUTURE REGULATION OF MONEY

- REQUEST FROM THE PUBLISHER

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access A Tract on Monetary Reform by John Maynard Keynes in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Economics & Investments & Securities. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.