- 210 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

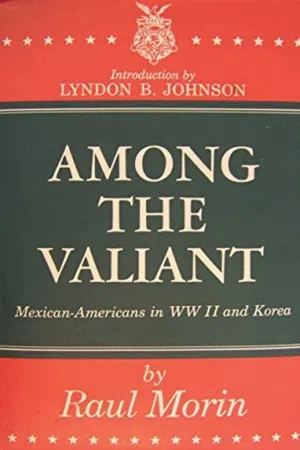

First published in 1963, this book by Raul Morin, who served in the 79th Infantry Division of the U.S. Army, was the first book to chronicle in detail the heroics of the Mexican-American soldier during World War II and Korea. It also provides information about the Chicano Medal of Honor recipients during these wars.

The book is a tribute to all American fighting men, "be they white, red, black, yellow, or brown. We feel just as proud of the Colin Kellys, the Dobbie Millers, and the Sadio Munemoris as we are of the Martinez', Garcias and Rodriguez'."

The book is a tribute to all American fighting men, "be they white, red, black, yellow, or brown. We feel just as proud of the Colin Kellys, the Dobbie Millers, and the Sadio Munemoris as we are of the Martinez', Garcias and Rodriguez'."

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Among the Valiant by Raul Morin in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & European History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1 — THE DAY OF PEARL HARBOR

Sunday, December 7, 1941. Every American was equally jolted by news flashes of the sneak attack on our fleet at Pearl Harbor. The news of the Japanese raid was just as alarming, but sounded more exciting to the almost-four-million persons of Spanish and Mexican descent living in the south-western part of the United States because it was being discussed in an exciting half-English, half-Spanish language that sounded twice as alarming to the stranger.

The whole world watched the latest developments with great interest. Experts on world affairs had been waiting for the day to come when America too would join what was shaping up as a second world war. On the morning of December 8th, history was repeated, the Congress of the United States of America declared war against aggressive axis nations just as had happened some twenty-odd years before when we entered World War I.

It was this nation that attracted the major attention. With the United States now involved, the war was sure to take on a different aspect. True, America as a nation was expected to undertake a big part with the other allied nations, but we, as individuals, were at this moment more directly concerned with our own little world—our own selves. We began to worry more about the part each of us would play rather than what America’s big part would be.

As I recall, it was in one of the small shops in picturesque Olvera Street—the tourist mecca of Los Angeles—where we gathered to discuss the exciting news of Pearl Harbor with friends and passers-by. The conversation ranged from sober to comical, with lots of joking on the many possible effects the war would have on us who were of Mexican extraction.

“Ya estuvo (This is it),” said one, “Now we can look for the authorities to round up all the Mexicans and deport them to Mexico—bad security risks.”

Another excited character came up with, “They don’t have to deport me! I’m going on my own; you’re not going to catch me fighting a war for somebody else. I belong to Mexico. Soy puro mexicano!”{3}

The person that made the first remark was, of course, referring to the many rumors that were started during World War I about having the Mexicans in the United States considered security risks when it was feared that Germany was wooing Mexico—insisting that Mexico declare war against the United States and align itself with the Axis powers—with the promise that if the Axis were victorious, Mexico would then be given back all the territory that formerly belonged to the southern republic.

The real down-to-earth fact was that the two who had made the remarks, Emilio Luna and Jose Mendoza, were first and second-generation Americans of Mexican descent, never having had ties with any other country. (Both Luna and Mendoza later went into the service, serving with honor in the Marine Corps and Army, as revealed in the following chapters). This was just their way of enjoying a little vacilada, a form of humor that serves as a morale builder. The idea being that by belittling your fellowman or your ethnic group, once you grasp the intent, it serves to bring those being kidded closer to one another.

At the time of Pearl Harbor, approximately 250,000 Americans of Mexican descent lived in and around the Los Angeles area. This is not to be confused with statistics released through the Mexican Consulate office which lists all persons of Mexican descent. We are concerned only with Mexican-Americans, those born here and those who have become American citizens since immigrating from Mexico and establishing residency here.

Other large Mexican-populated areas in California were Orange and San Bernardino Counties, and the sprawling San Joaquin and Imperial Valleys. This gave California a population close to 750,000 citizens and aliens of Mexican descent.

In other parts of the U.S.A., the state of Texas led with close to a million Spanish-speaking residents. The majority of them lived in the lower Rio Grande Valley and in the Counties of Webb, Bexar, Nueces, El Paso, Hidalgo, Cameron, and Willacy. New Mexico’s 248,000 were along the upper and middle Rio Grande Valley in the Santa Fe, Bernalillo, Socorro, Sierra, and Donna Anna Counties. Arizona’s total of Spanish extraction was 128,000. They were located mostly in the Maricopa, Greenlea, Pinal, Pima, and Santa Cruz Counties, with the Salt River Valley having the largest concentration of the Spanish-speaking population. Colorado numbered 118,000, the majority being in San Luis Valley in the south and the biggest concentration in Pueblo and Denver in the north.{4}

Thus, approximately 85% of the Mexican-American population was located in the five south-western states. Most of the other 15% lived in Kansas, Nebraska, Utah, Michigan, Pennsylvania, Wisconsin, Minnesota, Ohio, Missouri, Wyoming, Nevada, Indiana and Oklahoma, with the largest number in Illinois, mostly in Chicago. This totalled approximately 2,690,000 Americans of Mexican descent living in the United States. One-third were within the draft age limit. Most were second and third generation Americans by birth. A small number had been born in Mexico, largely in the frontier states of northern Mexico along the U.S. border, but had since become American citizens.

Along with other Americans, we all answered the call to arms.

II — OUR MEXICAN-AMERICAN BACKGROUND

The history of the Mexican-Americans in the south-west begins with the Spanish conquest in Mexico and the gradual colonization that extended into what was then the northern regions of Mexico. This territory included widely distributed settlements such as Texas, New Mexico, Colorado, Arizona, Utah, Nevada, and California.

As these areas were acquired by the United States after the Mexican War of 1846, the Mexican population remained and grew slowly through the process of immigration and by normal population growth. However, the extensive immigration of people from Mexico goes back to the early part of the 20th century.

In the latter part of 1910, the oppressed people of Mexico revolted against the tyranny of Porfirio Diaz who had been ruling them with an iron hand for 30 years. This bitter struggle that was to change the life of all Mexican citizens lasted for more than four years. It disrupted all family life and spread poverty, disease, and starvation.

To escape the hard rigors of La Revolution, the people began to flee across the border, into the United States. Thousands of Mexican families abandoned their mother country and sought sanctuary in the neighboring country. With no restrictions or immigration quotas to stop them, crossing over was an easy matter. Registration and the right answer to a few questions was about all that was required.

The war-torn families that crossed the Rio Bravo added to the existing large numbers of Spanish-speaking inhabitants of the south-west. They found much in common with the people who had been living in Texas, New Mexico, Arizona, Colorado, and California since the days that Spain had ruled. Many of them were descendants of the Conquistadores who had conquered the wild territories. Many others still held large land grants given to them by the king of Spain.

Throughout the years—under Spain, under Mexico, and lastly under the United States—these people had retained their language, their customs, and their religion. Integration between refugees of the revolution and the original settlers of the south-west occurred without any interruptions in the society of the two groups, due to the fact that both spoke the same language and otherwise lived much alike.

The type of employment for the new arrivals was not the most desirable nor the highest paid, but it was better living than that of the old country. In fact, it was more than they had expected in a new and strange land. They were offered jobs—which they hastily accepted—in lowly-paid, temporary, migratory work. Most of it was of the stoop-labor variety, such as agricultural field work, and common labor in railroad and construction gangs.

The border states were soon crowded with field laborers. Work became scarce and the pay lower. It was rumored that work was plentiful further north, and better in the middle-west and northern states. Newcomers and old residents then started migrating to Kansas, Missouri, Michigan, Minnesota, Ohio, Illinois, and Indiana.

During World War I, as early as 1916, the northern march was well underway, as recorded in a report made in Chicago to the Council of Social Agencies:

“Starting out from San Antonio, Texas, which was a distributing center for Mexican labor, they made their way north through Kansas City and St. Louis.

“The early Mexican immigrants came mainly as ‘enganchados’ (hooked ones), contract laborers, to work in agriculture, and the sugar-beet fields of Michigan, Wisconsin, Minnesota and Indiana. Another large and important group came north (Middle-west) as railroad section hands. Both groups came to perform seasonal work and at the termination of their respective labor contracts found themselves near such large centers as Detroit, Milwaukee, Gary, Indiana and Chicago.”{5}

BORN IN THE U.S.A.

It was the US-born descendant of the immigrants and early settlers who began to fill the role and assume more traits of Americanism. In the early days this was not an easy matter. I well remember that those first years were filled with surprises, pity, frustration and disappointments.

By virtue of having been born in the United States, we began on equal footing with other Americans. After a normal happy childhood, we ran into our first little surprise. We learned, first from our parents, then from our scrupulous Anglo neighbors, that we were of a different breed...we were Mexicans. We calmly accepted this fact, then went along with the teachers and instructors in school to learn Americanism: the English language, American History, laws and customs of this country. Surprise and puzzlement came at home when we tried to put into practice the things we had learned at school. We were often reprimanded, scolded and laughed at for such things as, speaking the English language, refusing to take the food we ate at home for school lunches, and for changing our name from Jose to Joe.

Our resentment came in our early teens from being shunned and teased by the Gringos, as we learned to call our non-Latin friends.

Pity came from the understanding souls around us and from the people of Mexico, who kept reminding us that we were neither Mexican nor American. As we grew up, we experienced frustration in trying to live the American way when we discovered all of our shortcomings. We had no special talents, no opportunities were offered, nor any high paying jobs. It was all an uphill struggle.

Living in our segregated neighborhoods did not help any. The custom we had of staying together, the plain discouragement that we received from moving to other sections of the town—all forced most of us to live “on the other side of the tracks.”

By the time we had matured, determination had grown in many of us; a determination that comes from awakening and realizing that we too were meant to be just as free as any other citizen. We too, were entitled to work, play, and to live as we pleased. Weren’t all Americans entitled to the same opportunities?

Had it not been for the giant depression in the late twenties, our first move toward social and economic improvement would already have been felt. We were determined to break away from the second-class citizenship status that many of us had been relegated to; however, the depression cut short the small gains we had made. Our progress came to a temporary halt.

The lean, long days hit us a little harder because very few of us came from wealthy families or had parents who owned successful business enterprises. The employment opportunities that had opened in factories, plants, in business and in commerce no longer existed as unemployment rose higher and higher.

In the late Twenties and early Thirties, the average United States Mexican laborer was classified in the unskilled or semiskilled category. Many who held good paying jobs in cities and towns had no other choice but to turn back to farm work and stoop labor in the field—to work in the much-hated jobs that for years, since the early border-crossing days, had been classified as ‘suitable for cheap Mexican labor only.’

Our educational progress was retarded everywhere when youngsters of high school age were forced to drop out of school to seek work and help the family earn a living. Many of us joined the CCC forestry camps, others worked in NYA and many took to the road roaming up and down the country, seeking work or just leaving to lessen the burden at home.

THE PRE-WAR YEARS

After 1932, the country began a recovery period, and so did we. We launched a new drive to improve our standard of living. Some good paying jobs were available again. We began to make good progress in economic improvement. Here and there young men were offered bigger and better employment opportunities, not only better paying jobs but also positions with a future.

More of our youth were finishing high school and going into college. Barriers were opened and many white collar workers began to appear. Stabs were made at civic organizations and in politics with small successes. Progress was made notably in the states of Texas and New Mexico, in sections where there ha...

Table of contents

- Title page

- TABLE OF CONTENTS

- FROM THE OFFICE OF THE VICE PRESIDENT

- DEDICATION

- PREFACE

- 1 - THE DAY OF PEARL HARBOR

- II - OUR MEXICAN-AMERICAN BACKGROUND

- III - DRAFTEES AND VOLUNTEERS

- IV - BEGINNING WITH BATAAN

- V - NORTH AFRICA

- VI - AT ATTU

- VII - THE MEDITERRANEAN

- VIII - WAR TIME U.S.A.

- IX - D DAY

- X - THE ETO CAMPAIGN

- XI - IN THE PACIFIC

- XIII - THE MEXICAN-AMERICAN MARINES

- XIII - IN THE NAVY

- XIV - THE AIR FORCE

- XV - END OF WORLD WAR II

- XVI - KOREA

- XVII - PRIVATE CITIZENS, FIRST-CLASS

- REQUEST FROM THE PUBLISHER