- 172 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

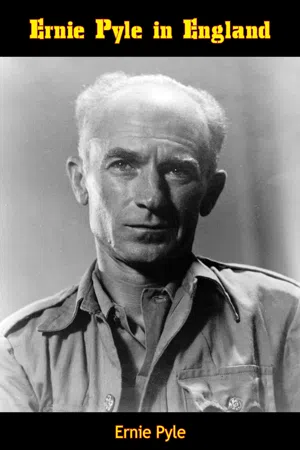

Ernie Pyle in England

About this book

Ernie Pyle's human and unforgettable picture of England under the Blitzkrieg—a deeply moving story of courage and faith.Ernie Pyle in England, first published in 1941, is the account of the journalist's stay in England, Scotland and Wales during the height of the German bombing blitz on London and other cities of the United Kingdom.Pyle, one of the most famous correspondents of the Second World War, had an easy-going, folksy-style of writing, making the book an enjoyable yet informative read about the conditions he encountered. His descriptions of the effects of the bombing, nights spent in air raid shelters, food- and gas-rationing, and daily life in London remain classic pieces of war-time reporting.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Ernie Pyle in England by Ernie Pyle in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & European History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

VII.—EXPEDITION TO THE NORTH

1.—FEAR, WITH LAUGHTER

York, February, 1941

Yesterday I received notice that if I didn’t get a move on I was to be expelled in disgrace from the Guild of Perpetual Travelers. So after six weeks of gathering moss in London, I packed my old sugar sack, shouldered my tin hat and gas mask, and hopped a northbound train to see how the war was getting on in the hinterland.

I took a 4 p.m. train out of London on the 160-mile ride to York. I got to the station half an hour early, and a good thing too, for within a minute after the train backed into the station there was hardly a seat left.

Easily two-thirds of the people on trains these days are in uniform. There are very few women. Soldiers on leave travel with full kit, including rifle. And a soldier with his full kit resembles a packhorse starting on a ten-day camping trip. They carry all this stuff because they must be ready at any moment. If the invasion comes while they’re at home, they simply report to the nearest army post and start shooting.

You might think that with a war on, half the hotels in England would have to close. But it’s just the opposite. The hotels have waiting lists, and if you don’t make reservations ahead you are liable to find yourself homeless.

That nearly happened to me in York when I arrived at eight o’clock in the evening. If it hadn’t been for a beautiful switchboard girl who called every hotel and boarding house in town I would have had to sit in the lobby all night. I fed her chocolates while she phoned, so we both profited.

Finally she found a place, a funny little semi-hotel that turned out to be grand. The owner was also the bellboy, and he built me a coal fire in the grate, put a hot-water bottle in the bed, and then stood and talked for half an hour.

There are many good-sized cities in England that haven’t been blitzed yet. York has had only a few raids, and only a small number of people have been killed by bombs in this city of 85,000.

As we stood in my room talking, I said to the owner: “What shall I do about ventilation tonight? I can’t open the blackout curtain with this fire going in the grate.”

He answered, “Oh, this terrible old building is full of drafts. You’ll get plenty of air without opening a window.” And he was right.

Until nearly midnight I sat before my fireplace reading the newspapers. I felt very strange, way up here in York. The city, covered with snow and very quiet, seemed terribly old, and nice in a Dickens-like way. Although it was February, you somehow expected to see Santa Claus coming down the chimney.

The papers had grave editorials warning about the coming invasion attempt. I read and thought, and read and thought, here alone in my ancient room in old York, and a funny thing happened. I had been in London so long I had acquired the London outlook, the London casualness, the London assurance that no matter what happens we can stand it. The Londoner’s psychology is like that of the aviator—somebody will get killed tonight, but it’ll always be somebody else, never me. But now, away from my eight million friends in London, this psychological cloak of safety fell away. Here in these strange surroundings, among people not yet hardened to bombs, here where the warning siren is an event, the whole horrible meaning of invasion shone clear before me like a picture. The frightful slaughter that even an unsuccessful invasion would bring grew stark and real to me for the first time. And I tell you I became absolutely petrified with fear for myself. I would have given everything I had to be back in America.

I probably wouldn’t have slept a wink if it hadn’t been for the bathroom. I discovered it after midnight, when everybody else had gone to bed.

The bathroom was about twenty feet square, and it had twin bathtubs! Yes, two big old-fashioned bathtubs sitting side by side with nothing between, just like twin beds.

Twin bathtubs had never occurred to me before. But having actually seen them, my astonishment grew into approval. I said to myself, “Why not? Think what you could do with twin bathtubs. You could give a party. You could invite the Lord Mayor in for tea and a tub. You could have a national slogan, “Two tubs in every bathroom.”

The potentialities of twin bathtubs assumed gigantic proportions in my disturbed mind, and I finally fell asleep on the idea, all my fears forgotten.

Some friends drove me over to Harrogate, which is one of England’s flossiest spas. It is some twenty-five miles from York.

Harrogate has curative waters, outlandishly huge hotels with prices so high they are famous, and in war or peace a stream of wealth and titles that stuns you.

Into this display of ease a German raider came, in day-time, and the people all stood in the street watching, thinking it was a British plane. They changed their minds when a bomb came down.

I asked if Harrogate had underground public shelters like London’s and a slightly cynical English newspaper friend of mine said: “Yes, but nobody ever goes into them. Harrogate is so flossy that everybody is afraid of being seen in a public shelter in the presence of someone who isn’t his equal.”

English place names fascinate me. There is a street in York called Whipma Whopma Gate Street.

I went down to the tiny lounge of my hotel and sat in front of the fire with six other guests for late tea.

This little hotel is the only place I’ve been in—outside of an officers’ mess—where they’ve had sugar in a bowl on the table, instead of just a cube for your coffee. The owner said he had found that by just leaving it out like that, putting people on their honor, guests used only half the sugar they did in peacetime.

There were two traveling salesmen at the hotel—one who sold shoes, and one who sold bread. One of them was from Sheffield, which was badly blitzed just before Christmas, and he had his wife and two boys with him. Due to the blitz, the youngsters had a six-week vacation from school, so they weren’t feeling so hard toward the fortunes of war.

These two boys were much more interested in asking about streamlined trains in America than in telling about Sheffield’s blitz. They have never been on a train. But they have studied mechanical magazines, and they told me all about the famous Royal Scot and Silver Jubilee streamliners.

When we did talk about bombing, I found that they knew as much about the characteristics of the various bombs as any air warden I’ve talked with. Yet the recent Sheffield blitz didn’t seem paramount in their minds at all.

Traveling salesmen have a tough time now. They can get plenty of orders but they can’t get the goods to fill them, because most of the factories are engaged in war work. Also, their gasoline is rationed. They’re allowed from five gallons a month upward, depending on how useful the government considers them. And they try not to do much night driving, for it is not so pleasant in the blackout. Yet, despite all this and despite the snowy roads and despite the fact that England is thickly populated and the speed limits are low, these traveling salesmen will do 200 miles in a day when they can get gas.

These two were on the road the next morning by daybreak.

Some friends and I, in a York pub, got into a conversation with a native Yorkshireman, and I couldn’t understand a word he said. I wouldn’t have let on, except that the friends with me were all British soldiers and they couldn’t understand him either. So finally we got into one of those long ridiculous discussions, the way you do in pubs, with us trying to analyze his talk and him trying to analyze ours. We all had a wonderful time—probably much better than if we had understood each other.

Not all Yorkshiremen talk the way this one did; not even a majority. Only on farms and in two or three other instances have I had trouble understanding Yorkshiremen. After I got home that night, and was still thinking about that fellow, the awful thought occurred to me that maybe he wasn’t speaking a local dialect at all, but simply couldn’t talk plain.

2.—YORKSHIRE FARM

Borough bridge, Yorkshire, February, 1941

The farmers of Yorkshire are getting a big play in the newspapers right now. For England realizes that she has got to turn this island into a big farm, what with Hitler trying to starve her to death by blockade. So I have been looking around some of the farms up here in Yorkshire.

The English farmer has had a terrible time since the last war. His standard of living has been abominably low. They say it is an amazing thing that anybody stayed on the farm at all.

The government did help a little, though not as much as ours has done. But now the government is doing things about the farms. It supplies loans, controls some prices, and in certain places does practically everything for the farmer except sitting on the fence and chewing a straw. But even so, the farm situation seems to me to be still fairly chaotic.

The main point is to get as much new land planted as possible. In many places they are plowing up cricket fields and golf courses. Every city and village has its “allotment plots/’ where townspeople with other jobs use their spare time working small patches in the city park, raising vegetables.

Despite England’s dense population, plenty of land is available. For example, the West Riding of Yorkshire in 1938 had roughly 750,000 acres in grass, and only 250,000 acres of tilled land. But in 1940 and 1941 more than 100,000 acres of this grassland has been plowed up and planted. Over here they call it “plowing out.” The old days of the great landholding squire with scores of tenants have pretty well passed since the last war. A majority of farm land is now owned in plots of about forty acres.

There is a hue and cry against the government right now for including farm hands in the next call-up for the army. The critics contend that the farms need all the experienced men they have, and that the army doesn’t need men at all. A “women’s land army” has been formed for work on the farms. It has 9000 members now, and another thousand are being recruited.

I dropped in to see one Yorkshire farm family. They are not exactly typical, for they live on government land and are much better off than most English farmers.

The head of the house is Robert Wray, who is getting along in years. He wears leather boots, and a shirt with a collar button but no collar. He has rheumatism and stays in the house on snowy days such as this one was. His son Richard does the work, and will until he is called up for the army. Mr. Wray’s daughter, who was down on her knees scrubbing the floor when I was there, had just been married and was still very blushy about it.

The Wrays have sixty acres, and practically a model house and barn, built by the government. They pay an annual rental of $4 an acre, and their yearly income is about $800.

They live three miles from town, and they don’t have a car or electric lights or a telephone. They live mostly in the kitchen in winter, but their kitchen is nicer than most farm kitchens. Instead of a regular cookstove, they have an open coal grate with ovens built into the wall beside the grate.

They have a bathroom, with nothing in it but a bath-tub. When I looked in, there was three inches of water in the tub, and it was partly frozen over. The toilet is an old-fashioned one in a fuel shed a few steps back of the house. Every room in the house, including the bedrooms, has a small coal grate, but these are seldom lighted.

The house in brick. Practically all English farmhouses are brick or stone, for timber is scarce. The bam is concrete, and the very last word. The Wrays keep about thirty head of cattle, a dozen pigs, a few chickens and no sheep. They farm with horses. All the stock is kept in separate stalls, spread deep with straw.

The war seems remote from the Wray farm, yet they are in it along with all the rest of England. Their home is never likely to be bombed, but they will feel a drastically tightening economy, and harder work, and one by one the absence of kith and kin who go away to fight.

On a wall of the Wray sitting room are two framed pictures. They are photographs of the young bride’s two uncles, in World War uniforms. One of them never came back from the last war. And before this one is ov...

Table of contents

- Title page

- TABLE OF CONTENS

- DEDICATION

- FOREWORD

- I.-ON MY WAY

- II.-ALL QUIET

- III.-MOST FATEFUL, MOST BEAUTIFUL

- IV.-THE HEROES ARE ALL THE PEOPLE

- V.-GUNS AND BOMBERS

- VI.-THE CAVE DWELLERS

- VII.-EXPEDITION TO THE NORTH

- VIII.-MURDER IN THE MIDLANDS

- IX.-YOU HAVEN’T SEEN ANYTHING

- X.-BOMBS DO THE DAMNEDEST THINGS

- EPILOGUE

- REQUEST FROM THE PUBLISHER