- 197 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

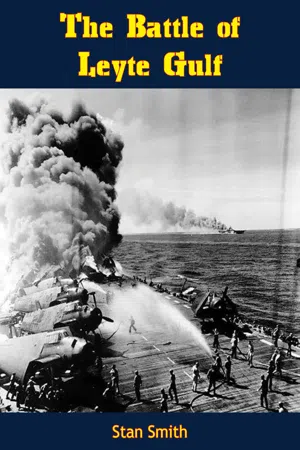

The Battle of Leyte Gulf

About this book

LEYTE!

The eight-day series of battles that took place on land, sea and air over thousands of square miles in October 1944 has gone down in history as the time of decision in World War II. The men who were there recall it with one unforgettable word...Leyte! In the pages of this new book, many years in preparation, those days of glory live again.

The eight-day series of battles that took place on land, sea and air over thousands of square miles in October 1944 has gone down in history as the time of decision in World War II. The men who were there recall it with one unforgettable word...Leyte! In the pages of this new book, many years in preparation, those days of glory live again.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access The Battle of Leyte Gulf by Stan Smith in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & European History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Chapter I — THE GATHERING CLOUDS

“IMPERIAL GENERAL HEADQUARTERS has the honor to announce the systematic destruction of the American Navy,” the announcer began. “In a swift, co-ordinated daylight raid, land-based Army bombers and units of the Navy’s air arm this morning found the Third Fleet all massed off Taiwan—”

The announcer’s voice broke dramatically.

He was Lieutenant Rikhei Tamai, a young naval attaché. At 11 A.M., October 14, 1944, Tamai rushed into the studios of Tokyo Radio brimming with the astounding news of Japanese success. It was “tide-turning news” and the first unabashed display of emotion in almost four years. Tears streamed down his face. Trembling, Tamai gripped the mike stand, sucked in his sobs and continued:

“Today, Japan’s fighting pilots, performing their duties with dispatch and brilliance, are finishing their masterful attack on the invading enemy. Already the United States has lost thirty-one warships! These include aircraft carriers, two battle ships, three cruisers and fifteen destroyers.”

Japan responded accordingly. A wave of hysteria, surpassed only by her Pearl Harbor strike, rolled inexorably over the home islands. Like a divine wind kissing the illusion of lotus blossoms over that fallow land, her best propagandists repeated the incredible battle reports as they streamed in every ten minutes. The news flashes electrified the nation. They were sent to distant bastions where the resolute and devout Shimpa (kamikazi) units were now grooming; millions danced in the gutted streets, filled with joy that seemed—for a while—beautiful and real.

And in the aftermath of these first bulletins, Emperor Hirohito, the man-deity, issued a special rescript and ordained that mass celebrations of the “Glorious Victory of Taiwan” (Formosa) be conducted wherever the nine-rayed Rising Sun cast its shadow. So apparently hypnotic was the overall effect of the bulletins that even General Headquarters, going strictly on visual and unconfirmed reports, unwittingly contributed to the magnificent hoax by issuing an independent statement that “no American invasion is contemplated for the Philippines.” Later that evening, the same source was heard to sigh in relief that “it’s about time for a radical modification of operations Sho-Go Japan’s last ditch defensive strategy.”

Tokyo Rose, interrupting her jam sessions frequently, jazzed American listeners: “All of Admiral Mitscher’s carriers have been sunk tonight—instantly!”

For three days and nights Radio Tokyo blotted out the air with preposterous claims of United States sinkings. The Third Fleet under Admiral William F. Halsey sagely maintained radio silence in the interest of the forthcoming battle—the real battle. To that moment, the air action off Formosa was the greatest single ship and landbased battle, but the outcome was considerably different than Japanese propagandists averred. Nippon’s air losses totaled 650 planes and pilots destroyed in the air and on the ground, compared to the Third Fleet’s eighty-nine losses—seventy-six in combat, thirteen operationally. Only Canberra and Houston, battered by Jap bombs but little more than wounded since fleet salvaged vessels started towing them safely away, testified to the air attack that Rear-Admiral Matsuda later asserted was “catastrophic” for the Japanese Empire.

Radio Tokyo spewed more joyous messages.

The Imperial Navy did its bit in the interest of journalistic probity, sending a float plane over Peleliu with leaflets that fluttered down on uninformed U.S. sailors grooming for the action of World War II.

“Do you know about the naval battle done by the American Fifty-eighth Fleet at the sea near Taiwan and the Philippine? Japanese powerful Air Force has sunk their nineteen aeroplane carriers, four battleships, ten several cruisers, and destroyers, along with sending 1,261 ship aeroplanes into the sea. From this result we think you can imagine what shall happen next round Palau upon you!

“The fraud Rousevelt, hanging the Presidential Election under his nose and from his policy ambition worked not only poor Nimitt but also Macassir like a robot, like this. What is pity you just sacrifice, you pay! Thank you for your advice of surrender. But we haven’t any reason to surrender those who are fated to be totally destroyed in a few days later.”

Admiral Halsey, at the time, was sitting in his battle plot. His leathery seaman’s face was screwed up in thought. He slowly wrote a short message to CINCPAC, Pearl Harbor. Then he turned up the receiver to hear what Tokyo Rose was saying now about the Third Fleet. A marine took his message to the radio shack. Minutes later, tall, white-haired Admiral Chester Nimitz, grinning from ear to ear, passed Halsey’s message to the American public:

““ALL THIRD FLEET SHIPS REPORTED SUNK BY RADIO TOKYO HAVE BEEN SALVAGED AND ARE RETIRING IN THE DIRECTION OF THE ENEMY.”“

On this grimly humorous note, the prelude to the battle of Leyte closed out. And the battle itself—the last and greatest naval battle in the history of the world—was about to see the death of an Empire. Halsey put his stubby legs on his desk, folded his hands in his lap and closed his eyes. The date was October 17, and the time was eight A.M. The first American Rangers were jumping out of landing craft and wading into Suluuan Island.

No withering fire from the lump of emerald cut them down. But on the outskirts of Tokyo, a small wizened man with the rank of four-star Admiral, Soenu Toyoda, blinked in mild bewilderment at the message that told him of the American landings. Toyoda studied the large wall map in his office in Japan’s Naval War College. Considering the recent flood of victory propaganda, Admiral Toyoda was quite calm about it:

“Alert the fleet for Sho (‘to conquer’) Operation.”

Twenty-four hours later, he gave the order that executed this command.

After the war, Admiral Toyoda, questioned at length on the situation confronting him in October 1944, said that in effect, “were the Philippines lost, even though the Fleet should be completely cut off, the shipping lanes to the south would be so completely isolated that even if the Fleet would come back to Japanese waters it would not be able to obtain its normal fuel supplies. And if it should remain in southern waters it could not receive supplies of ammunition and arms. There would be,” Toyoda added, “no sense in saving the fleet at the expense of the loss of the Philippines.” How to hold them was the question.

Despite the lack of fuel, and although the “remnants” of Japanese aviation had been obliterated in the battle that was to presage Leyte Gulf—the battle of the Philippine Sea—the actual position of the Emperor was not altogether hopeless. Japanese airmen and troops operated thousands of miles from home; Japanese airmen were only 500 actual miles from the scene so, therefore, they could fight in range of scores of airfields that they had built. Toyoda decided that wherever his enemies struck he would then rely on committing his surface craft, covered by land based aircraft. The actual commitment, predicated on these decisions, was called the Sho plan. It was one of the most daring naval operations ever undertaken.

Sho was devised to meet several alternatives: “An American thrust against either of the Philippines, or Formosa and the Ryuku Islands, or Kyushu, Shikoku and Hokaido. Each ‘plan’ was to be based on the full exploitation of the gunnery strength of the fleet, and land based airpower was to be substituted for carrier borne aircraft.”

Sho-One—Operation Alert, set for the early hours of October 25—characterized the determination of the Japanese to die fighting away from his homeland by fighting the big one elsewhere and seemingly in defense of those ill-gotten gains, the Philippine Islands.

Purely from the Japanese standpoint, Operation Sho-Go was the logical way to deal with the enemy, for if the enemy’s landings were thwarted before he had a chance to dig in and work his way into the Archipelago, Japan had a working chance for survival. With characteristic duplicity, the Oriental planning boards had devised a scheme which had offered, generally speaking, the bulk of the Japanese fleet as bait for Halsey’s gunners. This would a) lure the Americans away from Leyte and, b) give Admiral Takeo Kurita’s squadron, the most powerful single squadron in the extant Japanese Navy (five battleships, ten heavy and light cruisers and destroyers), the chance to strike the American forces in the process of their Philippine landings.

Further, it offered, if properly executed, a long-sought chance to inflict some heavy casualties on the invaders.

Phase three envisaged the use of the last squadron under Admiral Nishimura, coming up at the Americans from the south by way of the Mindanao Sea (they were based like Kurita’s squadron in Singapore) up through Surigao Straits and straight away into Leyte Gulf. On paper it was a very good plan, and the Japanese with a meticulous precision were quite up to it, things equal.

Then too, there were Combined Base Air Forces, using land based aircraft to hit the ships in Leyte Gulf, in addition to serving as air cover and reconnaissance for the Fleet Headquarters, soon to be fed the bulk of the kamikazi fodder. They had on tap only 400 landbased Navy Zeros, and the odds still were overwhelmingly in favor of the enemy though there was still the element of luck to be considered. History, it was argued by responsible commanders, had a way of repeating itself—except in this case one was expected to apply the reverse to the situation, particularly since Japan had practically no air arm and the U.S. did.

The remains of the once great armada could be assembled, however, and coupled into various dispositions. There was no question that Toyoda intended to use his fleet in a fight to the finish. One of his admirals, Ozawa, when questioned after the war, had this statement on the Battle of Leyte: “A decoy, that was our primary mission—to act as a decoy. My fleet could not very well give direct protection to Kurita’s force cause we were very weak, so I tried to attack as many of your American carriers as possible, and be the decoy or target of your attack....The main mission was all sacrifice.”

The Combined Fleet of Japan was organized into two parts, one composed of the bulk of the battlewagons and cruisers under Admiral Kurita based in the Lingga Islands, and the other of the remaining carriers denuded of most of their air crews, under Admiral Ozawa, and based on the Inland Sea. According to plan, Admiral Ozawa was to proceed to the invasion point and then, as his statement remarks, “to act as decoy, to lure the enemy carriers toward him.” Subsequently Admiral Kurita, under cover of land based aircraft, was to fight his way to the beachhead and destroy the enemy shipping. The whole plan revolved about strong surface gunnery forces, and was destined to get in where it could do the greatest damage. Little thought was given to its getting out again, nor was it expected that Admiral Ozawa’s carrier force would survive.

What the enemy hoped to accomplish by the attack was indicated in a general way by the Sho plan. A more pertinent question is: What effect could the operation actually have upon the Allied landing in the Philippines? It is doubtful that enemy intelligence was informed of the real situation at Leyte Gulf. In the first place, the greater part of the assault shipping had been “combat-loaded” at Pearl Harbor for the attack on the island Yap, and the cargos cut to correspond to the needs of that relatively small operation. When the Yap operation was abandoned at the last minute, these ships were diverted to the King II operation, with only very minor adjustments in the cargo of some vessels and none at all in others. Leyte Island, with the support of bases and air strips throughout the Philippines, was an objective vastly different from the tiny island of Yap. The result of the use of a Yap assault on shipping and the speedup of the landing schedule was a critical shortage of certain supplies, especially motor vehicles and the narrow margin of supplies of all kinds. On A plus Five day, the day Kurita and Mikawa planned to enter Leyte Gulf, the majority of our troops on Leyte had supplies ashore for only a very few days’ operations. Interruption of the flow of supplies, even for a short period, would have created an extremely difficult situation.

The American fleets concerned in this action were the Third and Seventh, Admiral William F. Halsey’s, and Vice-Admiral Thomas C. Kinkaid’s. The Third Fleet was labeled Task Force Thirty-eight, commanded by Vice-Admiral Marc A. Mitscher, and was subdivided into four task groups: 1) Vice-Admiral John S. McCain, 2) Rear-Admiral Gerald F. Bogan, 3) Rear-Admiral Frederick C. Sherman, and 4) Rear-Admiral Ralph E. Davison. In all, 738 vessels were organized into three distinct task forces. Among these warships were vessels of the Royal Australian Navy.

The basic orders under which the Third Fleet operated were contained in the operation plan of Admiral Nimitz. The commander of these forces was directed to “cover and support forces of the Southwest Pacific in order to assist in the seizure and occupation of objectives in the Central Philippines.” He was to “destroy enemy naval and air forces in or threatening the Philippine area and to protect air and city communications along the central Pacific axis.” However, “in case opportunity for disruption of a major portion of the enemy fleet offers or can be created, such destruction becomes the primary task.” Admiral Halsey was to operate through “the established chain of command,” remaining responsible to Admiral Nimitz, but “necessary measures for detailed coordination of operation between the Western Pacific Task Forces (Third Fleet) and forces of the Southwest Pacific’s (Seventh Fleet) would be arranged by the respective commanders.”

It was agreed that the Third Fleet would conduct carrier air strikes on the northern and central Philippines, beginning on A minus Four day and continuing through A-day, and that thereafter it would continue in “strategic support of the operation, effecting strikes as the situation at that time required.” As has often enough been pointed out, and most accurately by Van Woodward, the two men in command of the fleets participating in the battle for Leyte Gulf were diametric opposites in temperament. In military strategy they were obviously of one mind. But in military temperament they were entirely different. Halsey, for example, has been quoted accurately as saying, “I believe in violating the rules. We violate them every day. We do the unexpected—we expose ourselves to shore base plans. We don’t stay behind the battle with our carriers. But, most important, whatever we do—we do fast!” Commensurate with his statements of unorthodox nature is his famous victory pronouncement of 1943, about which Halsey later related that he knew “my statement could not possibly be true. I wanted to exaggerate as the Japanese exaggerate, to break down their morale.” While the enemy was proclaiming the destruction of his fleet after the Formosa strikes, Halsey broke radio silence with the remark that his sunken ships of course had been salvaged and were retiring at high speed toward the Japanese fleet.

Vice-Admiral Kinkaid, on the other hand, was transferred in November 1943 after the Aleutians campaign. He went from the Arctic to the tropics to assume command of the Seventh Fleet. After his forces had won the battle of Surigao Strait, the Admiral made the request of the correspondents interviewing him: “Please don’t say that I made any dramatic statements. You know that I am incapable of that.”

And so the lines are clearly drawn as to the military temperament of the two men.

Admiral Halsey had been with the Fast Carrier Force for only two months at the time of the battle for Leyte Gulf. When he came aboard his flagship New Jersey and assumed command of the Third Fleet on August 24 and, incidentally, inherited what is known as the “brain trust,” a formidable array of talents that have never been equalled, the Admiral had not exercised a command at sea for almost three years. His identification with the carrier war had arisen in the public mind from his command of a small-scale raid against the Gilbert Isl...

Table of contents

- Title page

- TABLE OF CONTENTS

- DEDICATION

- PREFACE

- FOREWORD

- Chapter I - THE GATHERING CLOUDS

- Chapter II - PRELIMINARY OPERATIONS

- Chapter III - RE-EVALUATION

- Chapter IV - GUERILLA ACTIVITY

- Chapter V - FIRST BLOOD

- Chapter VI - BATTLE OF THE SIBUYAN SEA

- Chapter VII - BATTLE OF THE SURIGAO STRAITS

- Chapter VIII - THE BATTLE OFF SAMAR

- Chapter IX - THE BATTLE OFF CAPE ENGAÑO

- Chapter X - POST MORTEM: TAKAO

- Chapter XI - THE MOP UP

- Chapter XII - THE PHILIPPINES RECAPTURED