- 726 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

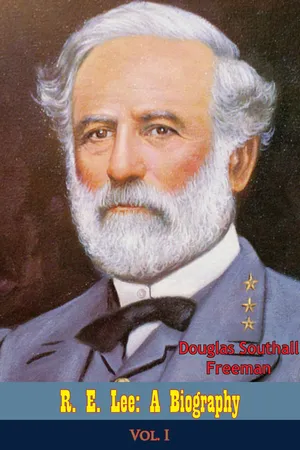

R. E. Lee: A Biography, Vol. I

About this book

Following the immediate critical success of Lee's Dispatches, author Douglas Southall Freeman was approached by New York publisher Charles Scribner's Sons and invited to write a biography of Robert E. Lee. He accepted, and his research of Lee was exhaustive: he evaluated and cataloged every item about Lee, and reviewed records at West Point, the War Department, and material in private collections. In narrating the general's Civil War years, he used what came to be known as the "fog of war" technique—providing readers only the limited information that Lee himself had at a given moment. This helped convey the confusion of war that Lee experienced, as well as the processes by which Lee grappled with problems and made decisions.

R. E. Lee: A Biography was published in four volumes in 1934 and 1935. In its book review, The New York Times declared it "Lee complete for all time." Historian Dumas Malone wrote, "Great as my personal expectations were, the realization far surpassed them." In 1935, Freeman was awarded the Pulitzer Prize for his four-volume biography.

Freeman's R. E. Lee: A Biography remains the authoritative study on the Confederate general.

R. E. Lee: A Biography was published in four volumes in 1934 and 1935. In its book review, The New York Times declared it "Lee complete for all time." Historian Dumas Malone wrote, "Great as my personal expectations were, the realization far surpassed them." In 1935, Freeman was awarded the Pulitzer Prize for his four-volume biography.

Freeman's R. E. Lee: A Biography remains the authoritative study on the Confederate general.

Trusted by 375,005 students

Access to over 1 million titles for a fair monthly price.

Study more efficiently using our study tools.

Information

CHAPTER I—A CARRIAGE GOES TO ALEXANDRIA

THEY had come so often, those sombre men from the sheriff. Always they were polite and always they seemed embarrassed, but they asked so insistently of the General’s whereabouts and they talked of court papers with strange Latin names. Sometimes they lingered about as if they believed Henry Lee were in hiding, and more than once they had tried to force their way into the house. That was why Ann Carter Lee’s husband had placed those chains there on the doors in the great hall at Stratford. The horses had been taken, the furniture had been “attached”—whatever that meant—and tract after tract had been sold off to cancel obligations. Faithful friends still visited, of course, and whenever the General rode to Montross or to Fredericksburg the old soldiers saluted him and told their young children that he was “Light-Horse Harry” Lee, but she knew that people whispered that he had twice been in jail because he could not pay his debts. Of course, he wanted to pay, but how could he? She could not help him, because her father had put her inheritance in trust. Robert Morris, poor man, had died without returning a penny of the $40,000 he owed Mr. Lee, and that fine plan for building a town at the Great Falls of the Potomac had never been carried out, because they could not settle the quitrents. If General Lee had been able to do that or to get the money on that claim he had bought in England, all would be well. As it was, they could not go on there at Stratford, where the house was falling to pieces and everything was in confusion. Besides, Stratford was not theirs. Matilda Lee had owned it and she had left it to young Henry and he was now of age. So, the only thing to do was to leave and go to Alexandria, where they could live in a simple home and send Charles Carter to the free school and find a doctor for the baby that was to come in February.

That was why they had Smith and three-year-old Robert in the carriage, with their few belongings, and were driving away from the ancestral home of the Lees. Perhaps it was well that Robert was so young: he would have no memories of those hard, wretched years that had passed since the General had started speculating would not know, perhaps, that the long drive up the Northern Neck, that summer day in 1810, marked the dénouement in the life drama of his brilliant, lovable, and unfortunate father.{1}

Fairer prospects than those of Henry Lee in 1781 no young American revolutionary had. Born in 1756, at Leesylvania, Prince William County, Va., he was the eldest son of Henry Lee and his wife, Lucy Grymes. From boyhood he had the high intelligence of his father’s distinguished forebears and the physical charm of his beautiful mother. He won a great name at Princeton, where he had been graduated in 1773. But for the coming of the war he would have gone to England to study law. Instead, before he was twenty-one, he entered the army as a captain in the cavalry regiment commanded by his kinsman, Theodoric Bland. Behind him had been all the influence of a family which included at that time three of the outstanding men of the Revolution, his cousins Richard Henry Lee, Arthur Lee, and William Lee.

His achievements thereafter were in keeping with his opportunities, for he seemed, as General Charles Lee put it, “to have come out of his mother’s womb a soldier.” A vigorous man, five feet nine inches in height,{2} he had strength and endurance for the most arduous of Washington’s campaigns. He made himself the talk of the army by beating off a surprise attack at Spread Eagle Tavern in January, 1778. Offered a post as aide to Washington, he was promoted major when he expressed a preference for field service; he stormed Paulus Hook on the lower Hudson with so much skill and valor that Washington praised him in unstinted terms and Congress voted him thanks and a medal; he was privileged to address his dispatches directly and privately to Washington, whose admiring confidence he possessed; he was given a mixed command of infantry and cavalry which was officially designated as Lee’s partisan corps; when he wearied of inaction in the North he was transferred to the Southern department in October, 1780, with the rank of lieutenant colonel. Although he was just twenty-five when he joined General Nathanael Greene in January, 1781, “Light-Horse Harry Lee was already one of the most renowned of American soldiers.

With not more than 280 men, Lee took the field in the Carolinas. The stalwart, dependable Greene was friendly and ready to take counsel. His theatre of operations was wide, the British posts were scattered. Surprises and forays invited the adventuresome commander. Marion and Sumter were worthy rivals. In Wade Hampton and Peter Johnston, father of Joseph E. Johnston, Lee found loyal comrades. Dazzling months opened before him. He was in the raid on Georgetown and won new honors at Guilford Courthouse. At least as much as any other officer, he was responsible for the decision of General Greene to abandon the march after Cornwallis and to turn southward instead, a decision that changed the whole course of the war in that area and brought about the liberation of Georgia and the Carolinas. Rejoining Marion on April 14, 1781, Lee cooperated with him in capturing Fort Watson and Fort Motte, and then advanced with only his own command to Fort Granby, which he bluffed into surrender, though not without starting some murmurs that he allowed overgenerous terms in order that he might receive the capitulation before the arrival of General Sumter. From Fort Granby, Lee swung again to the south. Marching more than seventy-five miles in three days, he reduced Fort Galphin, and had a large part in the capture of Fort Cornwallis at Augusta. His was the most spectacular part in the most successful campaign the American army fought, and his reputation rose accordingly. In the remaining operations of the year he was less successful, though he had the good fortune to be sent with dispatches from Greene to Washington in time to witness the surrender of Cornwallis at Yorktown.{3}

Then something happened to Lee. In a strange change of mental outlook, the tragedy of his life began. As soon as the fighting was over he became sensitive, resentful, and imperious. He felt that Greene had slighted him, that merited promotion had been withheld from him, and that his brother officers were envious and hostile. A curious conflict took place in his mind between two obscure impulses. One apparently was a desire to be master of himself and to remain in the profession for which he seems to have known he was best fitted. The other impulse was to quit the camps of contention for the quiet of civil life, there to win riches and the eminence he felt had been unjustly denied him in the army.

This inward battle may have had its origin in the restlessness of a soldier whose campaigning was over. Exhaustion and ill-health may have caused a temporary warp of mind. Resentment may have been at the bottom of it, the resentment that is so easily aroused in the heart of a young man whom praise has spoiled. More particularly, a love-affair then developing doubtless made Henry Lee discontented with his life. The mental conflict, in any case, was one that Lee felt himself unable to win by the exercise of will or of judgment, though he looked upon it as objectively as if it had been the struggle of another man. “I wish from motives of self, he wrote General Greene, “to make my way easy and comfortable. This, if ever attainable, is to be got only in an obscure retreat.” And again: “I am candid to acknowledge my imbecility of mind, and hope time and absence may alter my feelings. At present, my fervent wish is, for the most hidden obscurity; I want not private or public applause. My happiness will depend on myself; and if I have but fortitude to persevere in my intention, it will not be in the power of malice, outrage or envy to affect me. Heaven knows the issue. I wish I could bend my mind to other decisions. I have tried much, but the sores of my wounds are only irritated afresh by my efforts.”{4}

In this spirit Henry Lee debated—and chose wrongly. Early in 1782 he resigned from the army. He took with him Greene’s acknowledgment that he was “more indebted to this officer than to any other for the advantages gained over the enemy, in the operations of the last campaign,”{5} but he left behind him the one vocation that ever held his sustained interest.

For a while all appeared to go well with him. He seemed to make his way “easy and comfortable,” as he had planned, by a prompt marriage with his cousin, Matilda Lee, who had been left mistress of the great estate of Stratford, on the Potomac, by the death of her father, Philip Ludwell Lee, eldest of the famous, brilliant sons of Thomas Lee. Their marriage was a happy one, and within five years, four children were born. Two of them survived the ills of early life, the daughter, Lucy Grymes, and the third son, Henry Lee, fourth of that name.{6}

Following the custom of his family, Henry Lee became a candidate in 1785 for the house of delegates of Virginia. He was duly chosen and was promptly named by his colleagues to the Continental Congress, which he entered under the favorable introduction of his powerful kinsman, Richard Henry Lee. In that office he continued, with one interruption and sundry leaves of absence, almost until the dissolution of the Congress of the Confederation.{7} To the ratification of the new Constitution he gave his warmest support as spokesman for Westmoreland in the Virginia convention of 1788, where he challenged the thunders of Patrick Henry, leader of the opposition.{8} Quick to urge Washington to accept the presidency, he it was who composed the farewell address on behalf of his neighbors when Washington started to New York to be inaugurated.{9} The next year Lee was again a member of the house of delegates, and in 1791 he was chosen Governor of Virginia, which honorific position he held for three terms of one year each. Laws were passed during his administration for reorganizing the militia, for reforming the courts, and for adjusting the state’s public policy in many ways. Some dreams of improved internal navigation were cherished but could not be attained.{10}

In the achievements of these years Lee was distinguished but not zealous. His public service was all too plainly the by-product of a mind preoccupied. For the chief weakness of his character now showed itself, and the curious impulse with which he had battled before he resigned from the army took form in a wild mania for speculation. No dealer he in idle farm lands, no petty gambler in crossroads ordinaries. His every scheme was grandiose, and his profits ran to millions in his mind.

He plunged deeply, and always unprofitable Financially distressed as early as 1783-85, he put £8000 of hard money into some magnificent and foolish venture in the Mississippi country.{11} Losing there, he sought to recoup by purchasing 500 acres of land at the Great Falls of the Potomac, where he hoped to sell off innumerable lots to those who were to build a great city at the turning-basins of the canal. This project must have had real possibilities, for it won Washington’s approval and it interested James Madison. Despite an attempt to finance it in Europe the enterprise fell through.{12} Before Lee had abandoned all hope of succeeding with this scheme, he had pondered the possibilities of getting inside information on the financial plans of the new Federal Government, presumably in order that he might buy up the old currency and make a fortune by exchanging it for the new issues. In November, 1789, he presumed on his friendship with Alexander Hamilton to attempt to procure from the Secretary of the Treasury a confidential statement of the administration’s policy. Hamilton affectionately but firmly refused to tell him anything, whereupon this, also, had to be added to Henry Lee’s futile dreams.{13} A little later Lee was involved in transactions that prompted Washington to declare downrightly that Lee had not paid him what was due.{14}

By this time, though there never was anything vicious in his character or dishonest in his purposes, Henry Lee had impaired his reputation as a man of business and was beginning to draw heavy drafts on the confidence of his friends. His own father, who died in 1789, passed over him in choosing an executor, while leaving him large landed property.{15} Matilda Lee, who had been in bad health since 1788, put her estate in trust for her children in 1790, probably to protect their rights against her husband’s creditors. Soon afterwards she died, followed quickly by her oldest son, Philip Ludwell Lee, a lad of about seven.

Desperate in his grief, and conscious at last that he had made the wrong decision when he had left the army, Lee now wanted to return to a military life. He sought to get command of the forces that were to be sent to the North-west to redeem the Saint Clair disaster. When he was passed over for reasons that he did not understand, he was more than disappointed. “It is better,” he wrote Madison, “to till the soil with your own hands than to serve a government which distrusts your due attachment—even in the higher stations.”{16} For a time, he became antagonistic to the fiscal policy of the administration of his old commander and was sympathetic with the bitterest foe of the Federalists in the American press, Philip Freneau. He might formally have gone over to the opposition had he not been rebuffed when he made overtures to Jefferson, who seems instinctively to have distrusted him.{17}

If he could not wear again the uniform of his own country there was an alternative, to which Lee turned in the wildest of all his dreams. He was head of an American state, but he would resign, go to France and get a commission in the army of the revolutionaries! First inquiries led him to believe he would be accepted and be given the rank of major-general, but he had some misgivings about the ability of the French to victual and maintain their troops. Before setting out for Paris he decided to take counsel with Washington. “Bred to arms,” he confided to his old commander, then President, “I have always since my domestic calamity wished for a return to my profession, as the best resort for my mind in its affliction.” Washington...

Table of contents

- Title page

- TABLE OF CONTENTS

- DEDICATION

- FOREWORD

- ILLUSTRATIONS

- MAPS

- CHAPTER I-A CARRIAGE GOES TO ALEXANDRIA

- CHAPTER II-A BACKGROUND OF GREAT TRADITIONS

- CHAPTER III-FIRST IMPRESSIONS OF WEST POINT

- CHAPTER IV-THE EDUCATION OF A CADET

- CHAPTER V-SORROW AND SCANDAL COME TO THE LEES

- CHAPTER VI-MARRIAGE

- CHAPTER VII-THE ANCIENT WAR OF STAFF AND LINE

- CHAPTER VIII-LEE IS BROUGHT CLOSE TO FRUSTRATION

- CHAPTER IX-YOUTH CONSPIRES AGAINST A GIANT

- CHAPTER X-LEE STUDIES HIS ANCESTORS

- CHAPTER XI-AN ESTABLISHED PLACE IN THE CORPS

- CHAPTER XII-FIVE DRAB YEARS END IN OPPORTUNITY

- CHAPTER XIII-A CAMPAIGN WITHOUT A CANNON SHOT

- CHAPTER XIV-FIRST EXPERIENCES UNDER FIRE-(VERA CRUZ)

- CHAPTER XV-A DAY UNDER A LOG CONTRIBUTES TO VICTORY-(CERRO GORDO)

- CHAPTER XVI-LAURELS IN A LAVA FIELD-(PADIERNA AND CHURUBUSCO)

- CHAPTER XVII-INTO THE “HALLS OF THE MONTEZUMAS”

- CHAPTER XVIII-THE BUILDING OF FORT CARROLL

- CHAPTER XIX-WEST POINT PROVES TO BE NO SINECURE

- CHAPTER XX-LEE TRANSFERS FROM STAFF TO LINE

- CHAPTER XXI-EDUCATION BY COURT-MARTIAL

- CHAPTER XXII-THE LEES BECOME LAND-POOR

- CHAPTER XXIII-AN INTRODUCTION TO MILITANT ABOLITIONISM

- CHAPTER XXIV-COLONEL LEE DECLARES THE FAITH THAT IS IN HIM

- CHAPTER XXV-THE ANSWER HE WAS BORN TO MAKE

- CHAPTER XXVI-ON A TRAIN EN ROUTE TO RICHMOND

- CHAPTER XXVII-VIRGINIA LOOKS TO LEE

- CHAPTER XXVIII-CAN VIRGINIA BE DEFENDED?

- CHAPTER XXIX-THE VOLUNTEERS ARE CALLED OUT

- CHAPTER XXX-THE MOBILIZATION COMPLETED

- CHAPTER XXXI-THE WAR OPENS ON THREE VIRGINIA FRONTS

- CHAPTER XXXII-LEE DISCLOSES A WEAKNESS

- CHAPTER XXXIII-LEE CONDUCTS HIS FIRST CAMPAIGN

- CHAPTER XXXIV-POLITICS IN WAR: A SORRY STORY

- CHAPTER XXXV-POLITICS, THE RAIN DEMON, AND ANOTHER FAILURE

- CHAPTER XXXVI-AN EASY LESSON IN COMBATING SEA-POWER

- APPENDIX I-1-THE OFFER OF THE UNION COMMAND TO LEE IN 1861

- APPENDIX I-2-TOWNSEND’S ACCOUNT OF LEE’S INTERVIEW WITH SCOTT, APRIL 18, 1861

- APPENDIX I-3-THE SUMMONS OF LEE TO RICHMOND, APRIL, 1861

- APPENDIX I-4-THE STAFF OF GENERAL LEE

- APPENDIX I-5-GENERAL LEE’S MOUNTS

- REQUEST FROM THE PUBLISHER

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access R. E. Lee: A Biography, Vol. I by Douglas Southall Freeman in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & 19th Century History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.