eBook - ePub

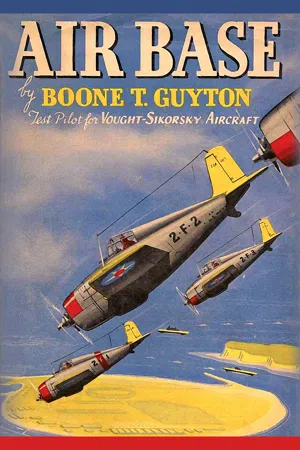

Air Base

About this book

Air Base, first published in 1941, by aviator Boone Guyton, is a fascinating look at the U.S. Navy's flying fleet shortly before Pearl Harbor and America's entry into the Second World War. In a style ranging from amusing to tragic and harrowing, Guyton describes his experiences as a Navy flyer. Following a year of flight-training at Pensacola, Guyton is based in San Diego with a carrier squadron aboard the

Lexington and

Saratoga. He describes the training cruises of the ship, the patrol flights, dive bombers, and war games, providing insight into the prewar Navy air force. Included are 8 pages of photographs. Following his naval service, Boone Guyton (1913-1996) worked as a test pilot in France until 1940. He returned to the U.S. and continued his work as a test pilot for Vought with the F4 Corsair. Following the war, Guyton settled in Connecticut and continued working as an executive for several aviation companies.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

Chapter I

The crash siren started up out of nowhere, wailed out into the night. It hit high pitch just about the time I had kicked off my last shoe and pulled on my pajamas for an eight-hour hop into dreamland. As I crawled back out of bed, jerked on trousers and sneaks, I thought to myself, this San Diego howler sounds just like the old one back at Pensacola. It brought the same results. There was a scuffle of scraping feet and slamming doors, some hurried talk with a few wisecracks. “Some green-eared ensign probably ground-looped out on the field.” “It’s my crib, and don’t stack the cards before we get back.”

Basil Alexander Martin, Jr., stuck his head around the corner. “Who the hell you suppose did this one?” he said in about the same tone I had listened to for a year back in training. Bud never did get excited about anything. As we hit the bottom step a head thrust through the screen door. “Everybody with a car get down to South Beach. One of Scouting Two’s planes went in off the breakwater and didn’t have time to drop a flare. We need a lot of lights.” The head disappeared.

Outside the officers’ quarters we crawled into “Hotdamn,” our rolling bucket of bolts. Cars were already streaming out toward the beach, and we fell into line. Landing planes came in one after another out of the black across Spanish Bight, then into the glare of the field floods, and sat down on the black tar, throwing long, fast shadows. The tires screeched and grump-grumped above the howling siren. A white flare was burning vividly out in the middle of the black landing mat, and we knew from training days that this was the recall signal for all planes still in the air. (It isn’t healthy for two or three planes to try circling around in the dark looking for a proverbial needle in the haystack. The danger of collision at night is quadrupled in the air, and base radio had probably already called all ships back to the field supplementing the flare.)

We went down past the last squadron hangar, around the corner back of the big balloon hangar, and by the rows of squatty stucco houses that bounded South Field. As we passed the officers’ club, a security watch officer pointed down to the edge of the water, where cars were pulling up into line, throwing their light beams up high. “Follow the last car, and get your lights on the water.” Bud pulled “Hotdamn” up alongside the station fire truck, whose big spotlight was playing out across the black Pacific Ocean. I kept wondering who had gone in and whether it could have been one of our class—Kelley, Jones, MacKrille. They had gone to Scouting Two, but surely they couldn’t be night-flying yet. We had arrived on the base only this evening, and Bud and I had been among the first to get orders to a carrier squadron based at North Island.

Up and down the white sand beach a motley crowd of officers, enlisted men, and even some women in evening clothes were scanning the inky surf for signs of a rubber life raft that would spell O.K. in their language. I’ve found it the same everywhere. Aboard a naval base—a small world in itself—the call goes out for help, and the shipmate who is in trouble gets it. From the third-class enlisted man in his barracks, to the admiral in his spacious quarters, the aid gathers as a family. White dinner jackets mingled with green uniforms, blue denims and half and half pajamas with service blues. Within twenty minutes a hundred cars had assembled along the shore line, and groups of people walked the beach, straining into the damp night for a Very signal or some sign from the occupants of the disabled plane. By now the last plane had landed on the field, and the silence was broken only by lapping waves and hushed talk.

Bud had come back from talking to one of Scouting Two’s pilots who had been flying. “It was Blackburn and one of the radio men. His engine cut on his final approach to the field, and he landed out about a thousand yards from the beach. He was too low to use his radio or flares. The ready plane standing by at the ramp is having some trouble getting started.”

Even as he spoke you could hear the unmistakable growl of the Grumman amphibian taking off from the bay on the other side of the island. A short few minutes later and he was circling over us, out to sea, his green and red running lights dipping down toward the water. Then on went the landing light, and out of the blackness came one, two, three parachute flares, lighting the water for several miles. The Grumman kept circling overhead. Half an hour. People were slowly registering that hopeless look as the minutes passed. No one left.

“There he blows!” The big chief mechanic on the fire engine bellowed out lustily, pointing down the beach. We started running and had almost made the spot when two wet figures jumped out of the little rubber raft and dragged it up on the sand. A big cheer went up and down the beach, and I would have given a lot to have had a camera and got a movie of that dramatic setting. Neither Blackburn nor his mechanic was hurt any, but they were wet and shivering.

“Rowed in from about half a mile out,” Blackburn said, wiping water from his face and eyes. “Plane sank almost immediately, and we just did get the boat out. Boy, these lights sure helped on the beach. The haze offshore is pretty thick.”

The crowd backed away to let them through, and before we could offer congratulations the station “meat wagon” (our crude term for ambulance) was hauling them off for a good rubdown and medical check. I thought what a lucky couple of boys they were to get away with an emergency landing at night without even the help of a landing light or flare. That water looked awfully black.

Then I thought back to the time Jimmy Abraham had landed at night in Pensacola with one wheel hung up in the belly of his plane. We were about as green about flying then as we were about service aviation now. I’ll never forget how we lined the runway at Corry Field that night, wishing so hard for old Jim that the wheel should have freed itself. He did a good job, though. When the plane nosed over and ended up on its back, Jim came out from under it with just a slight change in his profile. He now packs a beautiful Roman nose.

We found out that the flotation bags had worked on Blackburn’s plane but that the landing was pretty hard, and one bag had carried away before they had been able to get the life raft out. The plane had sunk shortly after, but they could see the lights of the cars lined up on the beach, so they had proceeded to paddle in. Uncle Sam was happy. A plane worth a few thousand dollars is nothing compared to the lives of pilot and mechanic. Once you have been through the Navy flight training, you never forget the sentence, “ We can always buy another airplane. You don’t buy pilots.

Back at the quarters, I crawled into the bunk once more. Downstairs the boys were still talking over the night’s occurrence, reiterating last week’s “close one,” and carrying on with some first-class hanger talk. But we had had enough for our first day aboard the base. I lay there, thinking back about a week before, when down at Pensacola the captain had issued his last admonition to his departing flock. We had stood beaming, at attention, gold wings secured on white uniforms, orders in hand.

“...and remember, gentlemen. When you get out to your squadrons in the fleet, Uncle Sam is putting you in commission like a new battleship. You are going out with a year of hard flight training behind you and a pair of wings. It is up to you to maintain the high standard set up by the Naval Air Force and to perform your mission to the best of your ability. Congratulations and good luck.”

That was all. We had shoved off, scampered across the country, and reported in to the officer of the day, Naval Air Station at North Island, San Diego, California. I kept remembering how often I had heard those phrases, “Now, when you get out to the fleet...when you get out in an operating squadron...!” We used to spend whole nights listening to the officers who had just come back from fleet duty tell about their experiences—how it felt to land aboard a carrier for the first time, what an operating squadron did, and how little we would actually know about flying until we had been through a couple of months of fleet duty.

Well, we were here—green, gawking, and self-conscious. But we were here and ready to have a mechanic paint our name across the fuselage of the ship we were to fly with the squadron. There was one thing about it. Action was spelled with capital letters out here, and there would be plenty of flying and a lot happening, both good and bad. By the end of the week our whole class of forty-two would report in, and I had already heard rumors of a party coming up at the officers’ club as a sort of initial icebreaker and get-together. I fell asleep, wondering what the new squadron would be like, whether the skipper—the old man—was hard-boiled or “just one of the boys” and whether the squadron was doing gunnery or bombing exercises. Dive-bombing Squadron Two off the carrier Lexington had held the annual fleet record for dive bombing several times. I hoped I still had my batting eye.

Chapter II

Mr. Guyton, may I have your orders?” the yeoman in the squadron office asked me, as I stood gaping at the pictures surrounding the long green table in the other room, somewhat overawed at these new surroundings. What I had expected to find on first entering a squadron ready room I don’t remember. I do remember that we had heard so much talk about “no romance in the fleet” and the like that we had leaned over backward from any of the glamour the movies had portrayed. Now I was looking at the walls of the “High Hatters,” the hot bombing outfit of the fleet, and the first impression was not quite so drab or uninteresting as the boys had depicted. I turned my orders over to the yeoman and went back to surveying my future home.

The long ready room was lined with chairs that surrounded the counsel table. Above them on the walls were pictures of formations, carriers, dogfights, and former officers of the unit. A big squadron flight board that hung at one end of the room by the coffee mess was covered with schedules of the day’s and week’s operations. Six small rooms opened out of the ready room, and the signs above the doors told the story—Flight, Navigation, Radio and Communications, Engineering, Captain, Executive Officer. It doesn’t take long to learn what each one of these divisions means and what specific duty each performs. You soon realize that a complete squadron of eighteen planes is organized, drilled, run, and kept in top shape right here.

Outside, the usual early morning ground fog was fast burning off.

“The squadron officers will be here any minute, sir,” the yeoman told me. “We muster at eight.” I looked at my watch and realized that in my eagerness I had arrived early. The coffee mess at the far corner of the room was already bubbling hard. (In the Navy coffee is as important a part of any ready room as wings to an airplane. I don’t see how a naval aviator can fly without it.) As I nosed around the room I wondered how Bud was doing up at his squadron, Marine Fighting Two.

“McClure is my name. Glad to know you.” We made the rounds. “Kane, Williams, Nuessle, Stephens. This is Ensign Guyton, gentlemen, just reporting in from Pensacola.” I was thinking that they could all tell that. My uniform, with its new shiny brass and bright gold wings stood out like a sore thumb among the salt-dulled braid of the older officers. It is the first distinction between newcomer and old-timer in the fleet. McClure, who I learned was flight officer, finished the introductions, and then we went in to see the skipper.

“Glad to have you aboard, Guyton. Draw up a chair.” I liked Commander Alexander from the start. He was a weather-beaten, rugged-looking gentleman, who looked as though he could handle any situation with cool precision. Well liked, usually called “Alex,” even by the junior officers, the skipper was one of the smoothest flyers in the squadron.

“Have you had your physical?” he said. I told him I hadn’t. “Well, you had best go right up to sick bay now and get it squared away. We are up to fly record bombing next week, and the rule is that every member of the squadron will fly. That means that you won’t have much time to practice, but we won’t expect any miracles. Just do the best you can.” This was the type of man for whom you felt like doing your utmost. Some men have the knack of leading, and some fall short. But old Alex was my idea of a born leader. I certainly hoped I could get some hits.

“Now, as for the squadron,” he went on. “Your job, outside of flying, will be assistant engineering officer under Lieutenant Nuessle. He will show you the ropes. You’ve been assigned Number Eighteen in the squadron, and Nuessle leads that section. If there is anything you don’t understand about what is going on here ask any of the officers, and they will be glad to give you a hand.”

He smiled, and I went out. There was a man I could really fly for, and Uncle Sam was fortunate to have commanding officers like him.

That was my welcome to the squadron. Before evening I had been to sick bay and passed a physical, met the rest of the squadron officers, and read the flight rules for North Island and the outlying fields.

The immediate outlying fields around an air base are nearly as important as the main flying field on the base. It is to these that you go to practice stationary-target dive bombing, carrierlanding practice (primary fieldwork), and such various activities as scouting exercises, rendezvous for mock warfare and battle practice, and familiarization in new types of aircraft. Several days later, when I had a chance to fly around to see these fields, I began to realize the military importance of such auxiliary points in time of actual warfare. When it was known when the attack would reach the base (by means of long-range patrol boats and scouting planes) all the squadrons could be flown to designated auxiliary fields. Here they would simply wait—or take part in defending the base—until the attack was over, leaving nothing but a blank landing field, with its surrounding shops, for the enemy to bomb.

Both the major belligerents of the present war are using this method so successfully that neither has sustained any heavy losses of aircraft destroyed on the home base. I had the list well in mind. Border Field, down Mexico way; Otay, cut out like a patch from the heart of sprawling Otay Mesa; Oceanside, on the coast toward Los Angeles; San Marcos, in the green, grassy valley of San Marcos River; Ocatilla, lying in the blistering heat of the Imperial Desert across the high range of Lagunas. Each had its circle target of white stones laid out at one end, and I was to look down my sights many times at those rings while trying to get steady in a dive for a bull’s-eye. You can’t foresee those days when you will be practicing dive bombing at one of these fields and suddenly have to land to help pull a broken shipmate from the wreckage of his plane because “something went wrong” and he didn’t pull out. It is good that you can’t.

The next afternoon I climbed into flight gear for my first squadron flight and gathered around the ready-room table with the rest of the squadron for last-minute instructions. You feel just a little proud sitting there with seventeen old-timers, ready to take off on a mission and waiting for the captain of the “team” to come out and issue the last-minute dope. I was still mentally munching a sandwich of course rules, air battle force instructions, and other pertinent information when the captain came in.

“We climb to twelve thousand ahead and south of the horizontal bombers. When we pick up the ship that is to be heading north just above the Coronados Islands I’ll put you in echelon.” The captain never minced words. Our orders came through to dive-bomb the radio-controlled Utah, a stately old battleship of yesteryear, and we were about set. This was just one of the long lines of “conferences” you took part in before squadron flights. They occur almost daily for the obvious reason of “dope delivering”—instructions and information, to be more formal. “The second division will close up on the first. I’d like to cut our attack time down, which means nose-to-cut tail diving. Any questions?”

“Where do we rendezvous after the attack, captain?” I looked down the table at him, past the seventeen old-timers, as I spoke, self-conscious as a bush-league shortstop in his first big game.

“Inboard toward the coast at two thousand. You are flying Number Eighteen, Guyton. “When you have finished your dive, call on the radio, and advise the squadron following us that we have completed our attack. All right, let’s go. And remember—we want some hits.”

You expect this direct and unadulterated lingo when you get set in the fleet, for time ...

Table of contents

- Title page

- TABLE OF CONTENTS

- Chapter I

- Chapter II

- Chapter III

- Chapter IV

- Chapter V

- Chapter VI

- Chapter VII

- Chapter VIII

- Chapter IX

- Chapter X

- Chapter XI

- Chapter XII

- Chapter XIII

- Acknowledgment

- Illustrations

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Air Base by Boone Guyton in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & European History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.