![]()

IV—REMBRANDT AND THE BIBLE

THE Jewish theme! In one sense it had long been known to Christian art—in scenes of biblical life; in pictures of Old Testament stories. The Jewish injunction against graven images had cast its prohibitive shadow also upon early Christian art, and many had raised the question whether it were permissible to make a representation of anything “that is in heaven above, or that is in the earth beneath, or that is in the water under the earth.” We now know that Jewish art, too, had given, in the early days of the Christian era, a more liberal interpretation to the restrictions contained in the Second Commandment than had formerly been supposed. In a Syrian synagogue of the third century of our era, in Dura-Europos, archaeologists have uncovered the ruins of a synagogue the walls of which from the floor to the ceiling were covered with scenes of the biblical story.{37} The principle that governed these portrayals was based upon the interpretation that the Second Commandment did not prohibit the representation of objects, but their worship. The emphasis was on “Thou shalt not bow down to them nor serve them.” And besides, it was more difficult for the Christian religion to forego the use of representative art than it was for the Jewish. The followers of the latter had learned to read already in their childhood, and were in consequence capable at all times of visualizing in their spirit the incidents of Bible history. Christianity, on the contrary, had made its inroads largely among illiterate peoples or, at any rate, among illiterate classes of the communities. To them the pictorial representation served as a means of instruction, or, as Pope Gregory the Great expressed it: “The picture takes the place of the reading for the population. They read at least upon the walls what they are unable to read in books.”

This Christian art placed scenes of the Old Testament in a natural and harmonious association with scenes from the New Testament and the lives of the saints. Both worlds, the Jewish and the Christian, were not opposed, but were intimately related in the Christian mind: the Old Testament formed the threshold of the promise; the New Testament its fulfillment. What lies hidden, in the first, steps into the light in the second. For this reason the Middle Ages never ceased to represent the Old Testament incidents, for these served to fortify the Christian faith, to the portrayal of which the entire art of the Middle Ages was dedicated.

The Renaissance, that followed upon the Middle Ages, continued these biblical portrayals with undiminished ardor. While the representation of historical and mythical phases of Antiquity achieved a wide popularity, there was no relaxation in the artistic treatment of themes of biblical significance, inasmuch as the Christian faith retained its intensity. On the contrary, the Renaissance provided many new aspects of Bible art. The beauty-cult of this period was embodied in pictures of the young and gentle Tobias or in the sculptured nudity of David. Its pleasure in the representation of physical grandeur was expressed in the approval bestowed upon such figures as Moses or the valiant-hearted Judith. Michelangelo even endeavored, in those incomparably beautiful frescoes of the Sistine Chapel, to depict his conception of the creative power of the Almighty in the scenes showing the creation of the world and of man made in God’s image.

Protestantism interrupted the progress of this trend for a brief period. The fear of idol-worship brought about a reaction against the inclusion of figures from the Bible and from the story of saints in the churches and chapels of the new creed. At the same time the realm of art was extended to include new provinces. Portraiture had already been added to its domain in the years of the Renaissance, and now it directed its interest to phases of landscape painting, the portrayal of scenes from daily life, objects of still-life, and the like.

But the creation of biblical pictures had not by any means been discontinued. This phase of art still flourished in all the Catholic countries: in Italy, in France, in Spain, in Belgium, and even in the Protestant lands of Northern Europe, including the little country of Holland. This fact must be especially emphasized, inasmuch as an American critic, John C. van Dyke, has advanced a peculiar theory regarding Rembrandt’s biblical pictures.{38} He simply denies the Rembrandt authorship of most of them, and attributes their origin freehandedly to his pupils. He bases his contention upon the fact that the Calvinist movement had placed a ban upon the presence of biblical pictures in the churches of Holland, and that the abovementioned newer themes had been given prominence in the homes of the Dutch people. A few of those biblical paintings, which this critic admits to have been the work of Rembrandt, are maintained by him not to have been executed upon commissions, nor to have been the product of any inner urge on the part of the artist, but to have been designed for the instruction of his many pupils, who later on continuously made use of what they had learned from their master.

It is truly astonishing to think that Rembrandt should have based his instruction upon examples of art which would never find purchasers. But setting aside this peculiar contention, van Dyke is mistaken as to the attitude adopted by the Hollanders in the matter of biblical pictures. The Calvinists, doubtless, excluded biblical scenes from their places of worship, and filled their private homes with portraits, landscapes and genre-pictures. Nevertheless, paintings of sacred themes also found places upon their walls. In one of Rembrandt’s etchings, “The Gold-Weigher,” a wall is adorned with a picture of “The Brazen Serpent,” from the well-known story about Moses. In like manner, scenes of biblical import continued to be part of the embellishment of the town halls and guild halls throughout the land.

It should further be borne in mind that the population of Holland included, besides the Protestants, a by no means inconsiderable number of Catholics, who did decorate their places of worship, if not ostentatiously on the exteriors, still within the walls, with scenes of biblical stories, and surely would have felt no hesitation in placing orders for paintings with Protestant artists when those of their own faith were not available. Many of Rembrandt’s paintings, whose subjects are foreign to Protestant ideology, doubtless originated in this manner.

A final argument in this connection may be based on the fact that purchasers of pictures depicting biblical themes included members of the new Jewish community, at least its Sephardi element. We have indicated in the foregoing that the latter placed a more liberal interpretation upon the ban against pictorial representations than had their forebears in the Middle Ages, or their contemporary Ashkenazi coreligionists. This led to their interest in and acceptance of portraiture. And now they went even a step farther, and admitted biblical pictures to their homes, though they did not permit them in their synagogues. We have shown, in a drawing made in 1665 by a Dutch artist (fig. 3), the interior of a room in the home of a wealthy member of the Jewish community. On the wall at the back hang two pictures, the lower part of one being clearly visible, while the greater part of the other is hidden behind a canopied four-poster bed. Although the subject of the latter picture is not recognizable, the former depicts the kneeling figure of a bearded man in a state of intense agitation, with outspread arms. An angel with arm extended is shown in the air, addressing the kneeling man. This is the angel who brings to Moses, at the Burning Bush, the revelation of his mission. The pathetic style of this painting has no bearing upon Rembrandt’s work, but we may assume from its presence in this home that the Jews had not only given commissions to Rembrandt for portraits but had also purchased from him pictures based upon biblical themes.

In one instance these pictures were not paintings, but etchings intended for use as illustrations for a printed text, the author of which was the Rabbi Manasseh ben Israel, to whom frequent reference has been made in these pages. The title of this book was Piedra Gloriosa; o, De la Estatua de Nebuchadnesar (The Glorious Stone, or Nebuchadnezzar’s Statue). Manasseh ben Israel wrote this book in 1654 or 1655, and it was published in a very small format, 2⅞×5½ inches, a miniature size much in favor at that time. The Rabbi shared the belief, entertained by many Jews of his day, that the Messiah would shortly make his appearance. He found evidence for this expectation in the dream of the Babylonian King Nebuchadnezzar, as related in the second chapter of the Book of Daniel. In this dream the king had beheld a statue, the head wrought of fine gold, the breast and arms of silver, the belly and loins of brass, the legs of iron, the feet in part of iron and in part of clay. Suddenly a stone detached itself, smiting the statue’s feet, which were destroyed together with the entire image. This stone became a great mountain and filled the whole earth.

Daniel interpreted the king’s dream by saying that the stone represented the Messianic Kingdom of God which would destroy all the kingdoms of the earth. This very stone, asserts Manasseh ben Israel in his work, served as the resting place of Jacob when there came to him the dream of the angels ascending and descending the ladder that extended between earth and heaven. It was also the same stone, he contended, that had later been hurled by David against Goliath. All this is comprehended in Daniel’s vision of the four strange beasts and the Messiah, who stands in prayer before the Throne of God, surrounded by the heavenly hosts.

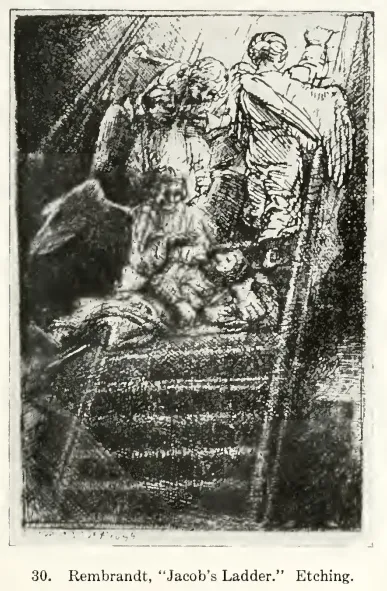

To provide illustrations for this elaborately fantastic dissertation, which had its inception in the ever-present yearning of the Jew for the Kingdom of God, Manasseh solicited Rembrandt’s co-operation, which the artist readily accorded. He made four etchings: the statue seen by Nebuchadnezzar; Jacob’s dream of the ladder of the angels; the slaying of Goliath by David, and the Messianic Vision of Daniel (not the Vision of Ezekiel, as has often been asserted in this connection).

Rembrandt must have experienced some difficulties in meeting Manasseh’s requirements, as repeated revisions were made in the plates. The statue of Nebuchadnezzar’s dream, for instance, exists in five different forms, the last of which bears inscriptions on various parts of the figure, indicating the kingdoms destroyed by the Divine Will.{39} In the etching of Jacob’s ladder (fig. 30) the figure of Jacob is not lying on the ground in the customary attitude, but is placed against the middle rung of the ladder, which symbolizes Jerusalem...