![]()

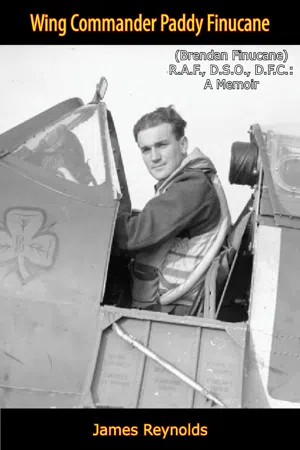

WING COMMANDER PADDY FINUCANE

[BRENDAN FINUCANE]

R.A.F., D.S.O., D.F.C.

IF SOMEONE asked me to describe Wing Commander Brendan Finucane R.A.F. in two words, I would say “bright and shining.” He seemed always to radiate light and lift of the spirit—his frequent smile, the way the corners of his generously drawn mouth went up—his witty friendly eyes—even his crisp dark red hair seemed always lifted by a breeze from “the upper air” he loved so well, the upper air in which from his eighteenth birthday until the day of July seventeenth, nineteen hundred and forty-two, he spent the greater part of his waking life. This smiling friendliness, this winning manner, caused him to be known as “Paddy” to all the world.

I first met Paddy in nineteen hundred and thirty-six when he was nearing his sixteenth birthday. A Saturday picnic it was, held on a rise of the Hill of Howth which commands the grandly sweeping panorama of the Wicklow Mountains, the gleaming white houses of Dalkey Strand, even the foam-ruffled edge of Killiney Bay itself where it curves in from the sea the like of a Saracen’s sword.

The picnic was an outing for boys from O’Connell School in Dublin, which Paddy attended.

The day was a pure wonder, clear and cool, not a cloud in the sky. A touch of life and the joy of living was given by the white canvas of sailing yachts, and the browns and greys, even green of wide-beamed fishing schooners far out in the Irish Sea. Gulls screamed and dipped into the water. There was a great peace over all, lovely to look back on, now. After we had consumed mountains of hot potato-cakes dripping with lashins of Kerry butter supplied by a man who went the rounds of the hill with a bar row on which was a charcoal stove, we downed our last bottle of ginger-beer, muttered a “God bless Guinness,” and stretched out on the turf—a little rest before the afternoon sports of obstacle races, vaulting, and rugby match should commence.

Paddy confided to me his two ambitions: boxing, at which he was very good, being lithe and a quick mover, and flying. Of the latter he said grinning, “To be always darting about in the upper air in a plane of my own, now that would be wizard.”

It was the first time I had heard his favorite word to express the utmost in pleasure, but it was not to be the last.

We discussed the manoeuvers of a plane flashing like a silver arrow in the path of the sun, making for Holyhead. As we watched, excitement widened his eyes; he spoke, more to himself than to me, “I want to fly more than anything, and I will one day.”

Paddy as a small boy became familiar with the heroes of Gaelic legend; aided by his swift intelligence they waxed warm and glowingly alive in his mind. He seemed equally enchanted by the Iliad of Homer, and the exploits and adventures of ancient Greek heroes.

Paddy possessed a splendid memory; never forgot what he read. He said to me one day, “Do you know, I might easily be that Greek lad Icarus—I’m that eager to try my wings.” As it turned out it was Icarus, and his quest of the reaches of the sky, which runs like a bright thread through Paddy’s rare poems.

I say rare, for there are very few he ever finished. He would jot down a line here and there, but he was so busy shooting Nazi planes out of the sky he had little time to finish poems.

In his last letters to me, and in his last letter to his mother, a sense of strain is apparent, a mounting tiredness lies ominously between the lines. I know he felt his responsibility as a wing commander intensely. In one letter he said “If I could only finish this muck, single-handed if I could, and get on with my life.”

The last time I heard directly from him he spoke of an accident caused by “leppin” a stone wall, returning from a comrade’s wake—a broken bone in his foot, painful and defeating. He so hated the idea of being grounded for six weeks by a cause in no way related to his fighting. Paddy put it like this in his letter: “When I was grounded by my broken foot it ached like hell, there was no sleep in me nights on end, I wrote a sonnet—I send you the first line—when it is polished a bit I’ll send you the finished job.”

Typewritten and clipped to the letter, it is this:

“I feel the shadow of wings across my face, Icarus wings, faltering in my flight.”

Probably he never finished it, I doubt it ever reached the “polishing” stage. In my opinion the sonnet is finished, for these two lines evoke the freedom, the shattering beauty of the infinite, the inevitability which places all airmen in a realm apart.

Many reviewers, since Paddy’s death, have spoken of how unassuming he was. It is very true, for he had the stark inspired simplicity of a youth with a star for achievement al-ways before his eyes.

Singleness of purpose linked Paddy’s thoughts. Early in life a guerdon of wisdom was tossed him by the gods, and he wore it gracefully to the last. Always, it has seemed to me, if any boy in this world had the “call” to fight an evil enemy with every fiber in his body—it was Paddy Finucane of Dublin-on-the-Liffey.

Paddy had no great hopes of outwitting death in this war, of that I am convinced.

Well do I remember the last time I saw him. We had dinner together in a Greek restaurant, came out into the shadows of Soho Square under a London street lamp, said good-by, I off to Dublin, he to Richmond in Surrey where his family lives.

We had stopped long over our wine, talking of Greece, of the lives of great heroes; the ancient, the medieval and the modern style of heroism just beginning to sweep across our vision.

I had a feeling all during dinner, that behind his thoughtful eyes lay the desire to play an immense part in the approaching big fight, a very much alive look, and an awareness. Paddy had at this time joined the R.A.F., and he was eager and champing at the bit to be off and away into the upper air.

Standing talking in low voices in the wine dark shadows of Soho Square we heard a droning; looking up we saw a formation of British planes winging away towards Dover: the night patrol. The sky was luminous with many stars; against the stars the formation made a pattern of strong black lace; the meshes seemed woven of strength and protection.

After the planes had faded into the dark horizon, Paddy quoted a line I had told him once, said on just such a night by a splendid Irish country woman in front of her thatched coteen at Adare in the County Limerick: “Sure the queen of heaven tonight has more stars than she knows what to do with.” He added, “Often and often I’m put to it not to collide with the stars up there, and me dodging in and out the clouds. Stars now, have a great hold over me.”

Slowly his smile faded, that fey look the Irish have veiled his eyes, and he said. “Do you know, even the big green shamrock—my fighting shamrock I paint on my plane—probably won’t save me for long. All I ask of St. Kevin is that I’m cut off clean—no ragged ends.”...