![Everyday Things in Ancient Greece [Second Edition]](https://img.perlego.com/book-covers/3020019/9781787204126_300_450.webp)

eBook - ePub

Everyday Things in Ancient Greece [Second Edition]

- 228 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Everyday Things in Ancient Greece [Second Edition]

About this book

First published in 1954, this is the Second Edition of the single-volume amalgamation of husband-and-wife team Marjorie and Charles Quinnells' three-volume anthology on Greek antiquity, originally between 1929-1932: Everyday Things in Homeric Greece, Everyday Things in Archaic Greece, and Everyday Things in Classical Greece.

Part I tells of the Trojan War and of the heroes who sustained the Greeks in their early struggles, with Homer cited as the main source.

Part II deals with the Archaic period (about 560 to 480 B.C.) ending with the great struggle between Greeks and Persians which culminated in the victory of the Greeks at Salamis, as related in the History of Herodotus.

Part III begins with the story of how the Greeks went to work after Salamis and built on the well-laid foundations a civilization which ever since has been regarded as Classical and closes with the account in the History of Thucydides of the struggle between Athens and Sparta and the failure of the Athenian Expedition to Sicily.

A comprehensive study of Ancient Greek History, revised in this edition by Greek authority Kathleen Freeman.

"In this book we have attempted to show some of the beautiful products of these artists, and their use in everyday life. It is our hope that the boys and girls who read it will discover that the Greeks were not a people extremely foreign and remote, who spoke a difficult language, but folk much like themselves, who lived and worked and played in the surroundings and among the objects we have depicted and described."—Preface

Part I tells of the Trojan War and of the heroes who sustained the Greeks in their early struggles, with Homer cited as the main source.

Part II deals with the Archaic period (about 560 to 480 B.C.) ending with the great struggle between Greeks and Persians which culminated in the victory of the Greeks at Salamis, as related in the History of Herodotus.

Part III begins with the story of how the Greeks went to work after Salamis and built on the well-laid foundations a civilization which ever since has been regarded as Classical and closes with the account in the History of Thucydides of the struggle between Athens and Sparta and the failure of the Athenian Expedition to Sicily.

A comprehensive study of Ancient Greek History, revised in this edition by Greek authority Kathleen Freeman.

"In this book we have attempted to show some of the beautiful products of these artists, and their use in everyday life. It is our hope that the boys and girls who read it will discover that the Greeks were not a people extremely foreign and remote, who spoke a difficult language, but folk much like themselves, who lived and worked and played in the surroundings and among the objects we have depicted and described."—Preface

Information

PART I—Homeric Greece

Chapter I—THE ARGONAUTS

IN any book which deals with Greece, the first name to be mentioned should be that of Homer. He was the great educator of Ancient Greece. Xenophon makes one of his characters in the Symposium say, “My father, anxious that I should become a good man, made me learn all the poems of Homer.”

Herodotus, the father of History, who wrote in the fifth century B.C., opens his book with references to the voyage of the Argonauts and the Siege of Troy, and by the far more critical Thucydides, who wrote at the end of the same century, Homer was evidently regarded as a historian to be quoted as an authority. If we follow their example, we shall be in excellent company.

We will begin with the voyage of the Argonauts, because in this tale we find the spirit of adventure and love of the sea, or rather use of the sea, which was to be so characteristic of the Greeks of Classical times. We may be able to capture some of the atmosphere of that Heroic Age, when gods like men, and men like gods, lived, loved, and fought together.

As to our authorities on the adventures of the Argonauts, Homer does not say very much, evidently thinking that his readers would know all about them. This is shown in the twelfth book of the Odyssey. “One ship only of all that fare by sea hath passed that way, even Argo, that is in all men’s minds, on her voyage from Æetes.” Fortunately for us, the details which were in all men’s minds were gathered together by Apollonius Rhodius, who lived in Alexandria in the third century B.C. The details we give are quoted from his book Argonautica.

This opens with a scene at the Court of Pelias, King of Iolcus, in Thessaly, who is disturbed because he has heard from an oracle “that a dreadful doom awaited him—that he should be slain at the bidding of one man whom he saw coming forth from the people with but one sandal”. When Jason arrives with only one sandal, having lost the other in the mud, it is not to be wondered at that he found his welcome a little chilly. “Quickly the king spied him and, brooding on it, plotted for him the toil of a troublous voyage, that on the sea or among strangers he might miss his homecoming.”

The troublous voyage was to sail to Colchis and find the oak-grove wherein was suspended the Golden Fleece, guarded by a dragon, and having found the Fleece, to bring it back. Here was a task worthy of heroes. Jason gathered together a band. First came Orpheus, the music of whose lyre “bewitched the stubborn rocks on the mountain-side and the rivers in their courses”. Then Polyphemus who, in his youth, fought with the Lapithæ against the Centaurs, and Heracles himself came from the marketplace of Mycenæ, and many others, sons and grandsons of the immortals.

The goddess Athene “planned the swift ship, and Argus, son of Arestor, fashioned it at her bidding. And thus it proved itself excellent above all other ships that have ventured onto the sea with their oars”—which only means that there was a streak of genius in the design of the Argo, because genius is a gift from the gods.

Jason was appointed leader, and preparations were made for launching the Argo. “First of all, at the command of Argus, they girded the ship strongly outside with a well-twisted rope, pulling it taut on both sides, that the bolts might hold the planks fast and the planks withstand the battering of the surge.” The heroes then dug a trench down to the sea and placed rollers under the keel. Then they reversed the oars, putting the handles outboard, and bound them to the thole-pins, and the heroes, standing on each side of the boat, used the projecting handles of the oars to push the Argo down into the sea. Then the mast and sails were fitted, and they drew lots for the benches for rowing, two to each bench.

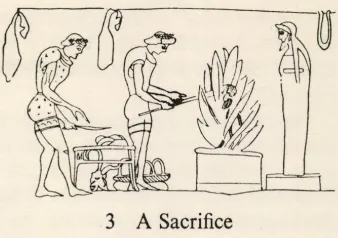

“Next, heaping shingle near the sea, there on the shore they built an altar to Apollo...and quickly spread about it logs of dried olive wood.” Two steers were brought, and lustral water, and barley-meal, and Jason prayed to Apollo to guide their ship on its voyage and bring them all back safe and sound to Hellas, “and with his prayer cast the barley-meal”. Heracles and Ancæus killed the steers.

Heracles struck one of the steers with his club in the middle of the brow, and dropping in a heap where it stood, it tumbled to the ground; Ancæus smote on the broad neck of the other with his brazen axe and cut through the mighty sinews; and it fell prone on both its horns. Quickly their comrades slit the victims’ throats and flayed the hides; they severed the joints and cut up the flesh, then hacked out the sacred thigh bones, and when they had wrapped them about with fat, burnt them upon cloven wood. And Jason poured out pure libations.

This was the general practice. Sacrifices were offered to the gods on all important occasions. The sacred thigh bones were burnt in their honour, and the joints eaten by the people in the festival which followed.

Achilles, the son of Peleus, who was to become a great hero himself, was brought by his mother to see the departure.

After the heroes had feasted and slept, they went on board the Argo and sailed away “Eastward Ho”, or, rather, rowed away. To the sound of Orpheus’ lyre they

smote the swelling brine with their oars, and the surge broke over the oar-blades; and on this side and on that the dark water seethed with spume, foaming terribly under the strokes of the mighty heroes. The ship sped on, their arms glittering like flame in the sunlight, and, like a path seen over a green plain, ever behind them shone their wake.

Presently they raised the tall mast in the mast-box, and fastened it with the forestays, pulling them taut on both sides, and when they had hauled it to the top-mast, they lowered the sail.

We cannot follow the Argonauts through all their travels, but the first part of their voyage was to Colchis, which, in Greek mythology, was situated at the eastern end of the Black Sea. There the Argonauts voyaged, hugging the shores as they went. They did not reach Colchis without adventure—heroes never do. In the Sea of Marmora they encountered insolent and fierce men, “born of the Earth, a marvel to see for those that dwelt about them, each with six mighty hands that he raises, two springing from his sturdy shoulders, and four beneath, fitting closely to his terrible sides”. The Argonauts were attacked by these Earth-children, but Heracles “swiftly bent his back-springing bow against the monsters, and one after another brought them to ground”.

Then for twelve days and nights fierce tempests arose and kept them from sailing, so they sacrificed to Rhea, the mother of all gods, that the stormy blasts might cease. “At the same time, at Orpheus’ bidding, the youths danced a measure, fully armed, clashing with their swords on their bucklers.”

At another time “around the burning sacrifice they set up a broad dancing-ring, singing, ‘All hail, fair god of healing, all hail!’”

It was in the Cianian land that Heracles and Polyphemus were lost, while searching for Hylas, who had been carried off by a water-nymph, and so the heroes sailed without them. Here it was that the heroes made fire by twirling sticks.

They next arrived at the land of the Bebrycians, where they found that all strangers had to box with King Amycus. Polydeuces stood forth as the Argonauts’ champion. A place of battle having been selected, “Lycoreus, the henchman of Amycus, laid at their feet on each side two pairs of gloves made of raw hides, dry and exceeding tough.” Just as modern prize-fighters tell the world how they are going to make mince-meat of their opponents, so Amycus warned Polydeuces that he was to learn “how skilled I am in carving the dry oxhides, and in spattering men’s faces with blood”. The fight was truly heroic, “cheek and jaw bones clattered on both sides, and a mighty rattling of teeth arose, nor did they give over from fisticuffs until a gasping for breath had overcome them both”. The fight was brought to an end when Amycus, rising on tiptoe, swung his heavy hand down on Polydeuces, who, sidestepping, struck the king above the ear and so killed him.

Their next adventure was in the Bithynian land, where they came to the assistance of Phineus, who was plagued by the Harpies, who came swooping through the clouds and snatched his food away with their crooked beaks. In return for their help, Phineus tells them of the dangers which still await them on the way to Colchis. So they were able to pass safely through the rocks which clashed together face to face.

It was in the land of the Mariandyni that Idmon, one of the heroes, was killed by a boar, and a barrow raised to his memory. Then they came to the land of the Amazons, but did not stop to fight the war-loving maids.

Next they came to the land of the Chalybes, who

take no thought for ploughing with oxen nor for planting any honey-sweet fruit; they do not pasture flocks in the dewy meadows. But they burrow the tough iron-bearing soil, and what they earn they barter for their daily food; never a day dawns for them but it finds them hard at work, amid drear sooty flames and smoke they endure heavy labour.

When they came to the island of Ares and its dangerous birds, “on their heads they set helmets of bronze, gleaming terribly, with tossing blood-red crests”; as well, they had to hold their shields roof-wise over the Argo to defend themselves from the feathers which the birds there could discharge from their wings like arrows.

On and on they went, until

the precipices of the Caucasian Mountains towered overhead, where, bound on hard rocks by galling fetters of bronze, Prometheus fed with his liver an eagle that ever swooped back upon its prey. High above the ship in the evening they saw it flying close under the clouds, with a loud whir of wings. It set all the sails quivering with the beat of those huge pinions. Its form was not the form of a bird of the air, but it kept poising its long flight-feathers like polished oar-shafts. And soon after they heard the bitter cry Prometheus gave as his liver was torn away; and the air rang with his yells until they sighted the ravening eagle soaring back again from the mountain on the self-same track.

Not long after they came to the mouth of the River Phasis, and “on their left hand was the lofty Caucasus and the Cytæan city of Æa. [Colchis], and on the other hand the plain of Ares and Ares’ sacred grove, where the serpent kept watch and ward over the Fleece, hanging on the leafy branches of an oak”. So the heroes anchored the Argo in a shady backwater, and there debated how they should achieve their end. Fortunately for them, Hera and Athene decided to come to their assistance, in a way we will tell later. The heroes’ own idea was the...

Table of contents

- Title page

- TABLE OF CONTENTS

- PREFACE

- EDITOR’S NOTE

- LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS

- RECOMMENDED BOOKS

- PART I-Homeric Greece

- PART II-Archaic Greece

- PART III-Classical Greece

- REQUEST FROM THE PUBLISHER

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Everyday Things in Ancient Greece [Second Edition] by Marjorie Quennell,C. H. B. Quennell, Kathleen Freeman in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & Ancient History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.