- 212 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

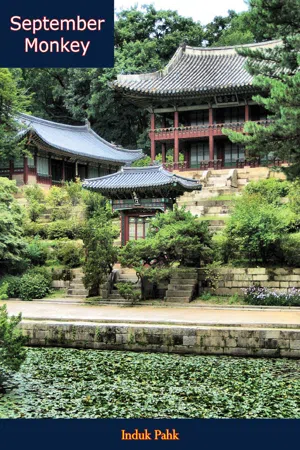

September Monkey

About this book

Centuries-old traditions and customs crumbled during the lifetime of this extraordinary woman who tells here the vivid story of her life in the old and the new Korea.

"To an illiterate Buddhist mother and a scholarly Christian father one day came a great disappointment—the birth of a daughter. 'If only this baby were a boy what a great career he would have,' mourned the father, noting the auspicious date on which 'September Monkey' arrived. But the mother—shortly to become a widow and a despised Christian as well—went about preparing her 'girl-boy' baby for the unheard-of experience of education, somehow realizing that if a new day for women in Korea were to come she would have to make it."

"To an illiterate Buddhist mother and a scholarly Christian father one day came a great disappointment—the birth of a daughter. 'If only this baby were a boy what a great career he would have,' mourned the father, noting the auspicious date on which 'September Monkey' arrived. But the mother—shortly to become a widow and a despised Christian as well—went about preparing her 'girl-boy' baby for the unheard-of experience of education, somehow realizing that if a new day for women in Korea were to come she would have to make it."

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

10—On Three Continents

In the late fall while attending a weekend conference I met Margaret Read of England who was one of the speakers. As we talked together I mentioned that I would like to visit Europe on my way home. After she had heard me speak, she told me she wished I could come to England to address the college students there, as they had never heard a Korean. She said she herself was planning to return to England after the conference and would be glad to contact the leaders of the Student Christian Movement in Great Britain and Ireland. A month later I received a letter telling me that everything had been arranged; they would like to have me come for three months. Overjoyed with this timely engagement, I accepted. I was to receive my MA. degree about February 1, so I arranged to sail on the SS. Bremen on February 10. Four and a half years previous I had arrived in San Francisco as a steerage passenger. Now I was returning home in a tourist cabin, via Europe, leaving behind many friends, and taking with me a new knowledge and many living memories. Surely America had given me a great deal.

After five days of smooth sailing we arrived in Southampton where many British battleships rode in the harbor, symbol of British naval supremacy. Going through customs I heard a new pronunciation of English. It was very interesting to me to listen to these Britishers talk. Train accommodations were different from any I had previously known, with compartments carrying four or six passengers, each compartment with its own door. Passengers did not chat informally as they did in America; they spoke only when directly addressed.

At Waterloo Station I was met by Miss Read who took me in a taxi to her home some distance away. It was Sunday and I noticed that all the stores were closed and the streets very quiet, even though London was a great metropolitan city. Ordinarily I do not eat much bread but that evening at supper I tasted the best homemade bread I had ever eaten, as well as English tea and plum pudding.

The next day my friend taught me how to use English money of all denominations, and this was doubly difficult for me as I had to calculate it in American valuation first and then in Korean. She also provided me with a map of London, including the tube systems, and told me that I would have two weeks for sightseeing before beginning my itinerary. She took me into the main thoroughfare of London and showed me the tubes, trolleys and buses, and the station where I should get off to go to her home—which was to be my home while I was in London. I was advised, also, to approach a bobby (policeman) if I got lost. One rainy day, going into the city during the rush hour, I had to cross a very wide street. There was no light signal and the bobby who was directing traffic saw me waiting. Stopping the traffic he came to me, took me by the arm, and conducted me across the thoroughfare. As the heavy traffic began to move again, I smiled as I thought of all this activity being stopped just for me—a lone Korean woman in the middle of London. Because of my happy experience while in England I hold a very warm place in my heart for all Britishers.

I knew that there were two Korean gentlemen in London at this time, one a student, D. S. Chang, working for his Ph.D. degree, and the other, S. S. Kim, president of Posung College of Seoul, on a tour. After I had got in touch with them, Mr. Chang, whom I had known previously in New York, took the time to show me around. In my roaming about the city I found the stores well stocked with all sorts of merchandise.

Miss Read introduced me to many of her interesting friends. Four o’clock tea, observed both in the home and at school, offered a time of relaxed discussion. We also found time to attend the cinema and to see The Barretts of Wimpole Street, Joan of Arc and Strange Interlude on the legitimate stage.

My speaking tour began at the girls’ college in Cambridge where I saw many traditional customs still being followed, as for instance, in the dining hall the use of an elevated table for teachers. I visited twenty-three colleges and universities in England, Wales, Scotland and Ireland. The meetings I addressed on campuses were sponsored by three groups—The Student Christian Movement, The Society of Geography and The League of Nations. Generally speaking, English students seemed very reserved but when they asked a question it was well thought out. They were more mature and also inclined to be more political-minded than the free and unaffected American youth. No doubt their attitude was due in part to their interests in their worldwide colonies.

When I went to the School of Geography at the University of Liverpool, I was almost overcome to see the maps of Korea made by the students. One of the professors said, “Mrs. Pahk, we want you to feel at home. Just look at all these maps.” Surrounded by such reminders of my homeland, I spoke to the students feelingly on “My Country and My People,” after which I was bombarded with questions. One student said, “We tried to get some references on Korea in the library but found very little. What we did find had been written by the Japanese, from their point of view. Now we would like to have your opinion on several questions. What do you think of the Japanese policy? Are things getting better in Korea? How is the farming situation?” et cetera.

After my lecture another student came to me and said, “Auh, Mrs. Pahk, you doan’t speak English atall.”

With much amusement, I inquired, “What do I speak, then?”

He replied, “You speak American.”

Mischievously I concluded, “I don’t speak American, either. I speak Korean-American,” and in typically English fashion he answered, “Right-o!”

At one church in Wales a young girl brought a Korean Bible to me as a gift. It had been printed by the British Bible Tract Society in Seoul. I opened the Korean Bible and in our tongue read the parable of the prodigal son. Then the girl who had presented the Bible read the parable in Welsh. Finally the minister read it in English. We ended our service with fervent prayers for England and Korea. I sent the Bible to my daughters in Seoul.

Back in London again, I attended a session of Parliament. The Labor party, headed by J. Ramsay MacDonald, was in power at that time. The whole bewigged procession, formal and reminiscent of history, was impressive and the freedom of speech exhibited on the floor surprised and excited me, especially the speech made by Margaret Bonfield who was then the Minister of Labor. The way questions were hurled at her and her quick retorts reminded me of a tennis match. To me a woman in the role of statesman was something new. I knew that the suffrage movement had originated in England and found that it still had plenty of modern exponents.

Facing homeward, I wished to visit other European countries. One day during a conference I had met a lady from Belgium who was on the board of the Y.W.C.A. in Brussels. When she learned that I had never been in Belgium she asked, “Wouldn’t you like to come to Brussels and speak to our students?” And before I could answer she told me that she would plan to have me for a three-day speaking tour, assuring me that my expenses would be taken care of. Without hesitation I agreed and on May 15 I left London, crossed the Channel, and took a train to Brussels where I was met and taken to the Y.W.C.A.

The next evening there was a large public meeting in one of the churches, sponsored by the Y.W.C.A. As I spoke in English my address was interpreted into French. I was told that I was the first Korean speaker they had ever heard. These people had suffered much at the hands of the Germans in World War I and naturally understood how we Koreans had fared under the domination of the Japanese. I was greatly gratified by their words of encouragement and by their display of spirit.

My Belgian hostess took me around the next day and pointed out places which had been destroyed by the Germans but were already restored by the people. She said, “My country is on the highway between Germany and France. You Koreans understand what that means.” As I saw the forward and upward look of this wonderful nation I thought how God blesses those who carry on courageously in spite of all adversities.

My next jump was Denmark. The chief reason for going to Denmark was to observe how the Danish Folk High Schools and Co-operatives were operated. Before leaving England I had contacted Peter Manniche who was head of the International People’s College in Elsinore where an experiment of the Danish system of adult education was being carried out. At a time when their country was almost on the verge of bankruptcy and had few natural resources, the Danes had decided to do something about their predicament and so they began to produce and distribute their products by co-operative effort. Their success was tremendous. Since in many ways their situation was analogous to ours in Korea, I wanted to learn all I could about their methods. On my way to Copenhagen by train I saw many evidences of their achievement—horses, pigs, cows and poultry in the green peaceful fields. This was in May, 1931.

From Elsinore where Dr. Manniche met me, I could see Sweden across the bay and almost felt as if I had returned to my birthplace in Chinnampo because of the mountains and the sea. When I arrived at the school there were about forty-five Danish students for the summer session and some fifteen visitors from England, the Continent and the United States. I was the only Oriental. The whole school appeared to be delighted to have a visitor from the Far East. Dr. Manniche asked me to sign the guest book, pointing to the signatures of some recent Korean visitors. They were all personal friends—two gentlemen from the Seoul Y.M.C.A. and a lady from Ewha College. It warmed my heart to know that occasionally my path crossed that of my countrymen.

Singing appeared to be one of the outstanding courses in the Folk High Schools. Folk songs were sung lustily at meals, between courses, after meals, before and after classes, and at bedtime, all of the students knowing about a hundred songs of hope and inspiration. “A singing people never dies”...“While they sing they become one” were their slogans. Gymnastics also figured prominently in the curriculum.

One night was designated as guest night and the townspeople were invited to meet the guests of the school. Nearly a hundred came on their bicycles which are their main means of transportation. Everyone enjoyed the singing, gymnastics and short speeches, after which folk dancing completed the program, followed by refreshments of black coffee, fruit and cookies. By this time I was thoroughly convinced that the Danish people were alive and progressive. Denmark was the first country I visited which had not been affected by the war, having remained neutral.

For two weeks I attended courses on co-operative marketing and international problems as related to the Danish people, classes conducted almost entirely by the discussion method in which all participated. The class was required to visit various farms, co-operatives and private homes in order to gain a proper perspective, and I learned that Denmark supplied most of the breakfast tables of London.

My first destination after leaving Denmark was Berlin. As I visited the campus of the University of Berlin I was impressed by the stubborn determination of the young people to overcome the defeat they had suffered in World War I. In England I had found the students reserved and confident; in Denmark they had been keenly interested in their own economic situation; in Germany they seemed bitter and resentful toward the Treaty of Versailles and bound to achieve, as a kind of vindication. As I traveled about the city and surrounding area I saw great activity among the youth who dressed in uniforms which somewhat resembled those of the Boy Scouts and seemed always to be marching under the leadership of Hitler. I saw model buildings called “Twenty-first Century” models, indicating the forward look of the people. One felt the spirit of determination which dominated Germany in 1931.

On the spur of the moment, I decided to go to Moscow but when I applied at the Russian Embassy for a tourist visa, I was told that they could not give me any assurance as to the length of time it would take to get my credentials. When I asked why, they said that was their business and not mine. I said that I would take a chance. And so I applied and waited three weeks, going to the visa office almost every day. Finally one morning I was told that I had been granted permission to go on to Russia the following Monday.

I boarded the train coming from Paris. At eight o’clock in the morning we stopped for half an hour at the Warsaw station which was crowded with working people. As I walked back and forth on the platform I thought of the suffering of the Polish people. Poland, too, had been partitioned several times and yet the people never ceased their efforts to regain their independence. How well our Korean saying, “Uttermost devotion moves the heavens,” applied to the Poles. At last at the end of World War I they were independent. Poland and Ireland were our models in pursuing our Korean independence. But when I arrived at the border of Russia I felt tension just from looking at the border guards and I left Poland with an uneasy feeling. When we reached the Russian city Niegorele, credentials and luggage were carefully examined and I changed my traveler’s checks into Russian rubles. We were moved onto a Russian train and I was assigned to a compartment with a young German woman who was going to Moscow to join her husband. The second day while the train stopped at Minsk for a half hour we got off to take a bit of exercise. A train from the opposite direction also had a stopover period and to my complete astonishment I met Dr. and Mrs. F. I. Johnson, whom I had known in Florida while on the Florida Chain of Missions trip. They had been to Moscow and were returning. We had time enough to drink a cup of coffee in their compartment and made the most of our precious minutes together.

Riding through the Russian countryside I was surprised to see the poverty and the many thatch-roofed houses in contrast to the domes and spires of the Russian Orthodox churches. I was interested to find a quaint practice in effect along the railway. When the train stopped at wayside villages, farm women were on the platform to sell homemade bread, cooked chicken and fresh fruits to passengers. Many who could not afford the luxury of dining-car service took advantage of these offerings. Others carried box lunches. There were six other tourists on our train: two couples, one from South America and the other from Germany; one man from France and another from Italy. I was again the only Oriental. When we arrived in Moscow we were met by a Russian guide and taken to a hotel. A multiplicity of placards printed in red were spread everywhere. It was early afternoon, and we were advised that our tour would begin the next morning after breakfast which would be served at ten o’clock. Next day at noon the guard made his appearance and we started out.

Of course the “glories” of the Communist regime were constantly brought to our attention. When we were taken to the tomb in Red Square where the embalmed Lenin was shown, we had to wait in line because there was so large a mob ahead of us. We visited a day nursery in which the government took care of children while their parents worked in periods of five days followed by one day of rest. The government did not acknowledge a “Sunday”; they had their own system of weeks. In parks speakers constantly indoctrinated their listeners with Red propaganda and ritual. Newspapers and illustrated bulletins extolling the Communist way of life were plastered on every available surface and laborers came between shifts for the occasional bit of news sandwiched in between these Red items.

Motion pictures were extensively utilized for propaganda; the people paid to be thus propagandized but the admission fee was small. Religion was ridiculed whenever possible but science was glorified along with communism. Marriage and divorce could be speedily transacted. We also visited a prison and an institution where former prostitutes could earn an honest livelihood by making hosiery.

As I moved about this great city I was horrified by the gaunt appearance of the people and by the breadlines for which each family was given tickets to purchase bread if the breadwinner had worked according to schedule. Soviet Russia was then in the midst of her Five Year Plan. The men wore no hats as they had none. About three o’clock every morning, the streets were dominated by youth groups singing and shouting in their great rumbling trucks. Stalin’s pictures were everywhere. Food was scarce. Our schedule called for lunch at three with dinner at nine but frequently the meal was delayed while food was located. We should be very patient with the common people of Russia for all they have gone through. It was a real relief to get away from such an atmosphere but at the same time I felt much concern, realizing that some great evil force was working against a free society.

En route to Vienna I changed trains at the Russian border and again in Warsaw. During the night the train crossed two border lines, Poland to Czechoslovakia and Czechoslovakia to Austria. Each time this happened customs officials came into the compartment, examined passports and luggage, and asked about each passenger’s destination and reason for traveling. I noted that this interrogation was made by a number of officials, each doing some very small part; one examined the passport, another stamped it, still another certified the luggage, and so on. When I asked one harmless-looking Czech official why they had so many men doing little jobs, he replied with a twinkle in his eye, “That’s the way we solve the unemployment problem.” But behind the twinkle in his eye there was another story. Many stormy days were ahead for his country because of her Sudetenland on the German border. I wondered what the future of this twelve-year-old republic would be.

We arrived in Vienna in the early morning. Since I had just one day to spend, I decided to take a regular sightseeing tour to see the Blue Danube, the palaces, museums and other sights. A couple from California in typical American fashion invited me to have dinner with them at the hotel. Then on to Switzerland, Europe’s winter playground, home of the League of Nations and other international organizations. Early the next morning the snow-covered Alps were illumined by the rising sun. I had made no contacts with anyone but had no difficulty in finding a room in a nice pension in Geneva. A parade, with colorfully dressed marchers and excellent music, and a showing of merchandise and fine produce from the twenty-two cantons of Switzerland gave me an unexpected opportunity to get a bird’s-eye view of the people and their products. Switzerland and Denmark were the only countries in Europe where I found the people enjoying life.

Although the Swiss have no national language but use French, German or Italian depending upon the locale, their spirit was unmistakably Swiss. This tiny country has succeeded for centuries in remaining neutral and keeping free from war even though surrounded by powerful neighbors. Wherever I went I asked about this tradition and the reply was invariably the same, “We train our people to defend their country but not to meddle in the affairs of othe...

Table of contents

- Title page

- TABLE OF CONTENTS

- DEDICATION

- Foreword

- I-Introducing September Monkey

- 2-A Girl-Boy

- 3-A Boy-Girl

- 4-Life in Ewha

- 5-College and Prison Life

- 6-In the Belly of the Whale

- 7-Jump Across the Pacific

- 8-American Student Days

- 9-The First Oriental Traveling Secretary

- 10-On Three Continents

- 11-The New Approach

- 12-Taking Korea to America

- 13-War Years

- 14-Liberation

- 15-Korea becomes Known

- 16-Lotus

- 17-Cultural Mission

- 18-Cultural Mission Continued

- Appendix

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access September Monkey by Induk Pahk in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & Central Asian History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.