- 71 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Rail Transport and the Winning of Wars

About this book

James Alward Van Fleet (March 19, 1892 – September 23, 1992) was a U.S. Army officer during World War I, World War II and the Korean War. Van Fleet was a native of New Jersey, who was raised in Florida and graduated from the U.S. Military Academy. He served as a regimental, divisional and corps commander during World War II and as the commanding General of U.S. Army and other United Nations forces during the Korean War. "This survey reviews the role of railroads in national security. It is based upon both personal observation and recorded experience of the effect of rail transport, or the lack thereof, on the outcome of campaigns and the winning of wars."

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Rail Transport and the Winning of Wars by James A Van Fleet in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & Central Asian History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

LESSONS FROM EXPERIENCE

“How could the Chinese Communist Armies in Korea supply themselves in hostile territory 200 miles from their Manchurian base and in the face of the terrific interdiction program of the United States Air Force and Naval Air?”

This amazing logistical performance of the enemy raised questions never fully answered at Eighth Army Headquarters. We knew they were getting the bulk of their supplies by rail. We knew the location of all rail lines. We had air and naval supremacy. But in spite of all our air and naval interdiction attacks, their railroads continued to keep them supplied, even to the point of building up reserves for offensive actions! How could they do it?

Enemy Logistics in Korea

The air effort by our pilots was magnificent and did tremendous damage. The armed aerial reconnaissance, the night intruder strikes, the massive Operations STRANGLE and SATURATE, the naval blockade and gunfire by ships offshore, and the sabotage operations by our raiding parties and friendly guerrillas—our whole interdiction program—caused vast destruction.

Repeatedly I was assured by my own staff, and by the Air Force and Naval Air, often supported by photographs, that “a mile or more of rails at critical points” or “the bridges at Sinanju” or “the East Coast Line” were “out for good.” But always, a few days later, locomotives pulling trains were operating at these very locations! In short, we were witnessing, this time to our own military disadvantage and frustration, another demonstration of the capacity, the durability, and the flexibility of railroads under war conditions.

Without ground pressure by Eighth Army, June 1951 to July 1953, the enemy by his standards was having a good time—enjoying ample supplies at the battleline and casting insults at Panmunjom. The Korean war more and more became a matter of logistics. Perhaps had Eighth Army withdrawn voluntarily to the tip of the peninsula, thereby doubling the length of enemy supply routes, and at the same time furnishing additional lucrative targets for our pilots, the Reds might have collapsed. Our air people share that view. My own position is that if all arms—Ground, Sea and Air—had struck together the pressure would have been too much for the enemy. With Eighth Army ordered on the defensive, the air effort could not win by itself.

My Concern With Transport

As a combat commander in World War II, Greece, and Korea, I had to concern myself constantly with transportation matters. When Napoleon made his famous statement that “an army travels on its belly,” he meant that troops go no farther and no faster than supplies of food, clothing, ammunition, and equipment can be moved. He could have added that a commander can maneuver and put into battle no more troops than his logistical resources can support.

Hence, the commander must be always preoccupied with relationships between his assigned task, his available combat strength in manpower and matériel, and his transport resources. He must likewise take into account the corresponding factors on the enemy side, and their day-to-day comparison with his own. He must continuously try to strangle the enemy by efforts to destroy or impair hostile supply. To direct these efforts most advantageously, he must know—or quickly learn—how to evaluate the transportation potentialities of various types of carriers available and where are their areas of greatest usefulness.

In accordance with the military doctrine of economy of effort his attacks against the enemy will be directed at points of greatest vulnerability or best reward. To this end, knowledge of relative liability to damage from hostile attack and ability to repair damage and restore service is essential to the commander. Need for this knowledge is reinforced and sharpened by ever-present awareness that his own transport is sure to be the object of corresponding enemy attack. Since the commander’s ability to stay in action and carry out his mission depends upon being able to frustrate such hostile activities, and keep his supply lines open, he has a lively interest in knowing the defensive and recuperative possibilities of each form of transport on his side.

It is basic, therefore, that a combat commander has to be concerned with transport logistics; the supply of his own forces, and the denial of supply to the enemy. My experiences in World War I, in World War II, in Greece, and in Korea convince me of the soundness of our military doctrine that railroads occupy the primary and basic consideration in any logistical plan. Other means of transport, important as they are in specialized situations, are supplemental or auxiliary.

Why Railroads are Primary and Basic

The story of logistical supply during the Korean conflict, both for the enemy and for United Nations forces, is proof once again of the indispensable role of railroads in war. Neither the enemy nor ourselves could have carried on without the tonnage which rails carried to the battleline.

During World War II railroads in the United States moved 90 per cent of military freight and 97 per cent of all organized military passenger movements. Railroads in Korea moved 98 per cent of all tonnage and troops passing through Pusan, the principal and at times the only port.

Modern wars of the last hundred years have closely followed railroads, or else railroads themselves have closely followed the battlefront. This is the lesson strikingly illustrated again and again in our own War Between the States, in World War I, in World War II, and in Korea. While these last three wars were fought overseas, the tremendous movement of supplies and men started in the continental United States. That movement was dependent upon railroads. Movement in military language is called “mobility” and “flexibility”—cardinal principles of the system of supply in which the United States stands pre-eminent.

On the home front, transportation must first move raw materials to factories and recruits to training centers. Then the finished products move to the places where needed. On the battlefront, transportation keeps the armies mobile, permitting commanders to sustain offensives or to make quick changes to meet tactical situations as they arise. Without transportation in sizeable amounts, war either becomes static or takes on the form of guerrilla operations.

A vast body of military experience goes to show that only railroads can supply the quantity and quality of transport needed to support modern armies. As Maj.-Gen. Frank A. Heileman, Chief of Transportation, U.S.A., said in 1952:

The railroads only have the capacity to meet all military traffic requirements in the United States. A combination of all other types of carrier service, exclusive of railroads, would not meet our requirements.

Later developments have not changed this essential military doctrine. In an address on 13 March 1956, Major-General Charles G. Holle, Deputy Chief of Engineers, U.S. Army, referring to the “vast scope and variety of service demanded by the armed forces”, said:

The changes in military planning brought about by the nuclear age will in no wise diminish the need for such services and may well increase them....I might add that even under the atom bombs which fell on Hiroshima and Nagasaki railroad-type structures stood up among the best.

General Holle added that “flexibility and mobility—construction power and transportation power—are absolutely vital factors in national survival—more so in this atomic age than ever before.” With reference to the part of the railroads in providing this flexibility and mobility of transportation power, General Holle declared that “in case of natural disaster, as in the case of war, the railroads move up from the ‘necessary’ category to the ‘vital’.”

Failure to Interdict Red Supply Lines

From the very beginning of Communist aggression in Korea, U.S. air power was used to impede the enemy’s progress. In addition, the U.S. Eighth Army and the Republic of Korea Forces systematically destroyed all rail and highway bridges during their southward withdrawal. The enemy, however, was able to repair damage and push south to the Pusan perimeter. Even there he appeared to have ample supplies and considerable reinforcements, in spite of damaged transportation systems.

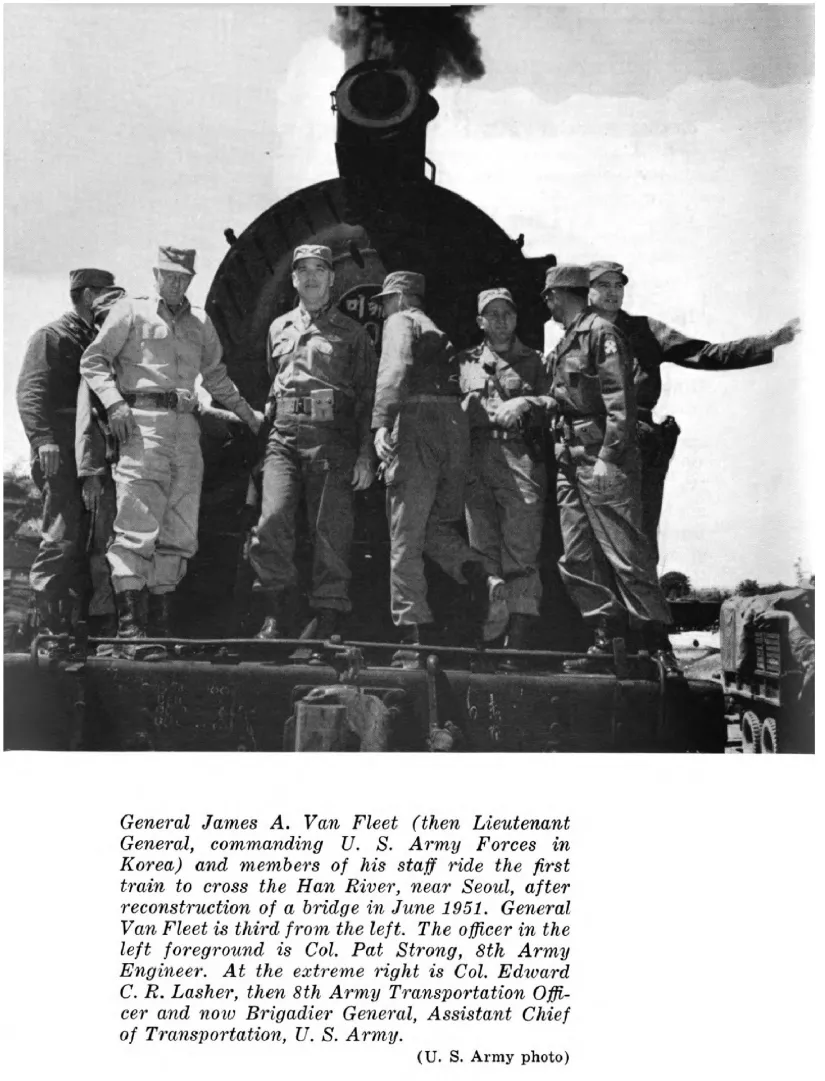

By late October, 1950, U. N. forces had delivered their counter-offensive, including the famous amphibious landing at Inchon, and had driven north almost to the Yalu.

When Chinese Communist Forces entered the war in strength in early November, 1950, aircraft carriers of Task Force 77 were given, for the first time in naval history, the mission to assist in isolation of a battlefield. North Korea was divided into two areas of responsibility, with the Navy confining itself to the northeast and the Air Force to the northwest portions. In the words of the Navy:

...the task of air power—land and sea based—during the following twenty months was to sever the Korean Peninsula at the Yalu and Tumen Rivers, undercut the Peninsula, and float the entire land mass out into mid-ocean, where interdiction, in connection with a naval blockade, could strangle the supply lines of the Communists and thereby force their retreat and defeat.

The announced Far East Air Force mission beginning on 5 November 1950 was

...to effect a complete interdiction of North Korean lines of communications, the destruction of North Korean supply centers and transport facilities, and North Korean ground forces and other military targets which had an immediate effect on the current tactical situation.

The task at the time seemed easy, and yet air power failed to isolate the battlefield. It became evident that individual rail cuts could be quickly and simply repaired, since there were ample supplies of lumber and unused rails, and, of course, unlimited manpower.

Results of Operation “Strangle”

Far East Air Force experienced similar frustration in carrying out Operation STRANGLE. Fifth Air Force was given the mission to carry out the stated purpose of STRANGLE

...to interfere with and disrupt the enemy’s lines of communication to such an extent that he will be unable to contain a determined offensive by friendly forces or be unable to mount a sustained offensive himself.

This operation, in one form or another, occupied U. N. air forces for some ten months.

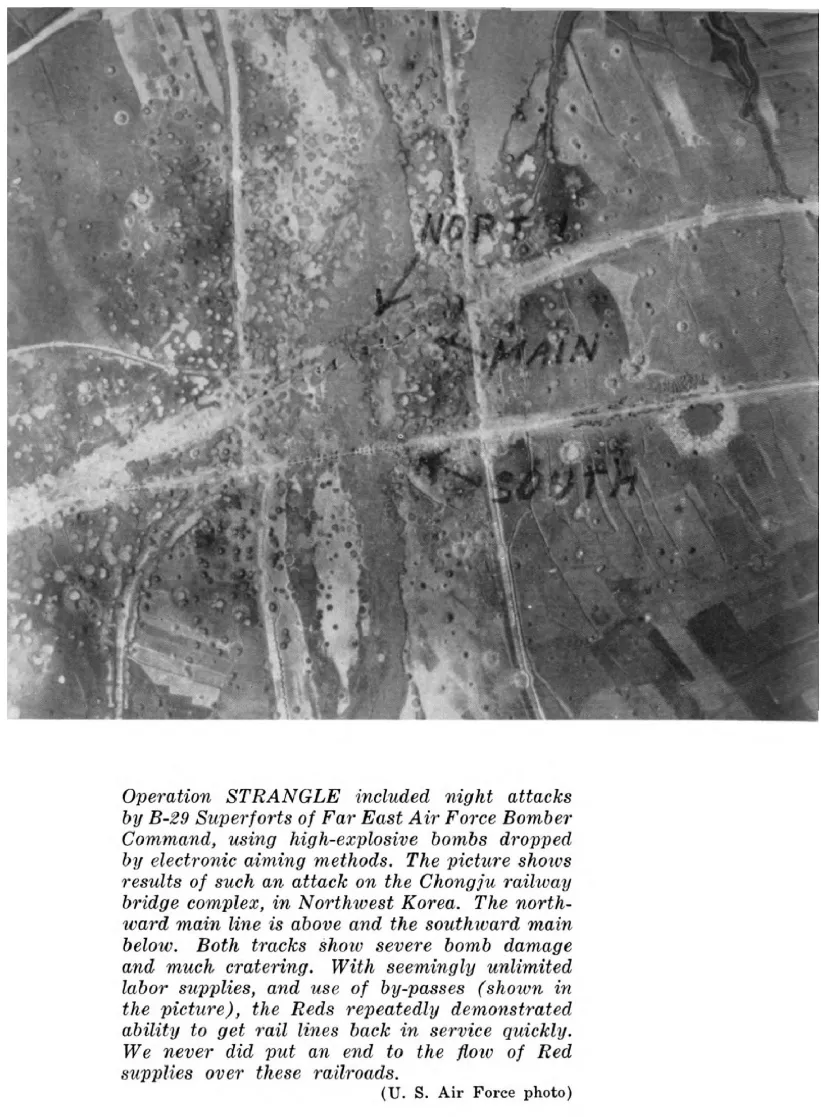

On the basis of its analysis of logistical factors involved, Fifth Air Force decided that it would be most profitable for its aircraft to destroy the North Korean rail system, forcing the enemy to use a fleet of 6,000 trucks to do what the railroads could do with 600 box cars. Because Fifth Air Force did not have the strength to complete the rail interdiction plan in reasonable time, it shared the program with the Navy and the Far East Bomber Command.

Initiated on 18 August 1951, STRANGLE had good success for some three months. Sudden initiation of the attacks apparently took the Reds by surprise, and floods at the end of August aided by washing out key bridges. From the outset, the Reds demonstrated great ability to repair rail cuts, and they gained in efficiency at the same time that Fifth Air Force destructive ability was on the decline as the result of improvement in enemy anti-aircraft fire and other countermeasures. By mid-November, photographs taken 24 hours after an attack would very seldom find a rail cut unrepaired. In December it was found that the enemy, beginning at dusk, could repair a rail cut within eight hours. They also displayed proficiency in bridge repair and in operating over badly damaged stretches of track. They built bypass bridges which required con...

Table of contents

- Title page

- TABLE OF CONTENTS

- Introduction

- Illustrations

- LESSONS FROM EXPERIENCE

- CAPACITY

- DURABILITY AND RECUPERATION

- FLEXIBILITY

- ECONOMY

- VERSATILITY

- CONCLUSIONS